Archeological artifacts from Yemen or as it was named in antiquity, Felix or Southern Arabia are rare as hens’ teeth. Moreover, given the political situation in Yemen, Ethiopia and Eutria it may be a long time until real scholarship resumes on this subject. The south and the north were homes to two entirely separate Semitic peoples: the Sabaeans in the south and the Arabs in the north. The Sabaeans were also called the Himyarites or the Yemenites, the Sabaeans had from a very early period adopted a sedentary way of life in the relatively lush climate of southern Arabia. The Sabaeans lived on two major two trade routes: one was the ocean-trading route between Africa and India. The harbors of the southwest were centers of commerce with these two continents and the luxury items, such as spices, imported from these countries. But the Sabaean region also lay at the southern terminus of land-based trade routes up and down the coast of the Arabian peninsula. Goods would travel down this land-route to be exported to Africa or India and goods from Africa and India would travel north on this land-route. This latter trade route had tremendous consequences for the Arabs in the north and the subsequent history of Islam. For all along this trade route grew major trading cities and the wealth of the south filtered north into these cities. It was in one such Arabian city, Mecca, that Islam would begin.

The ancient Yemeni alphabet branched from the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet in about the 9th century BC. It was used for writing the Old South Arabian languages of the Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramautic, Minaic (or Madhabic), Himyaritic, and proto-Ge’ez (or proto-Ethiosemitic) in Dʿmt. (see my post on Felix Arabia). There are no vowels, as in Hebrew. Zabūr is the name of the cursive form of the South Arabian script that was used by the ancient Yemenis (Sabaeans) in addition to their monumental script, or musnad, a similar situation to that in Egypt. The cursive zabūr script, also known as “South Arabian minuscules”, was used by the ancient Yemenis to inscribe everyday documents on wooden sticks in addition to the rock-cut monumental musnad letters displayed above. The alphabet’s mature form was reached around 500 BC, and its use continued until the 6th century AD, including Old North Arabian inscriptions in variants of the alphabet, when it was displaced by the Arabic alphabet. If you look closely you can identify letters from the alphabet in the carved stone tablets above.

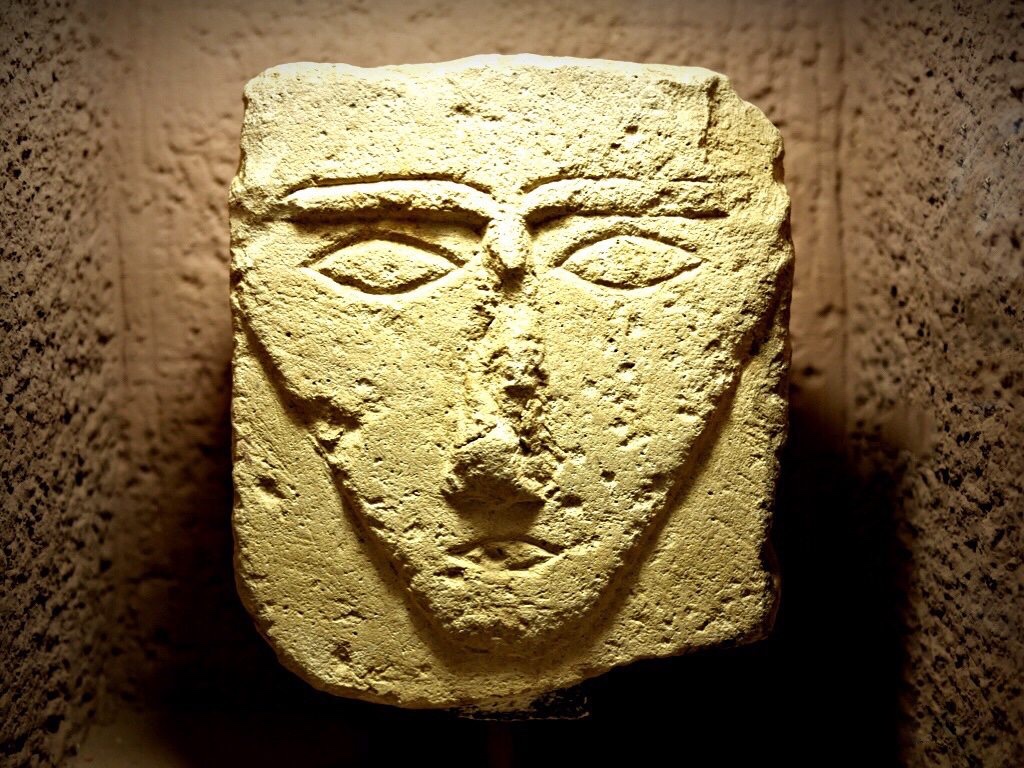

The people who inhabited Saba, and the kingdoms around it were often at war, though they were occasionally united and formidable, yet remain elusive to modern scholars. The subjects funerary carvings, in alabaster, are stylized and originally, these detailed alabaster heads were set into much rougher and more primitive limestone pillars. It’s as if the limestone was a shroud over the softer, more lifelike facial carving. The distant past, which so often comes down to us through the memory of warriors, priests and royalty is almost always serious. Not these figures. They seem more relaxed, more comfortable with their silence, than the statues of other cultures. It is as if the faces are sweetly smiling through the centuries to our modern eyes.

Aside from serving as an intermediary for trade between the east and west, the real business of Southern Arabia was incense. Unlike their northern Arabian counterparts, they stayed put, grew rich off trade in frankincense and myrrh, and raised stone cities, temples and dams to capture the annual monsoon rains, with which they made the desert bloom. Their incense burners are characteristically square and boxy, much like their alphabet, buildings and art. They are also quite large for incense burners, indicating a degree of wealth since incense was an expensive commodity. These may have been an ostentatious display of wealth and power and designed to show potential buyers that they were in the right place to purchase incense.

No dates were available on these three bas relief plaques but we can surmise certain things from them. Dromedaries may have first been domesticated by humans in Somalia and southern Arabia, around 3,000 BC. Camels actually originated in North America and spread to Asia via the Bering land bridge. The last camel native to North America was Camelops hesternus, which vanished along with horses, short-faced bears, mammoths and mastodons, ground sloths, sabertooth cats, and many other megafauna, coinciding with the migration of humans from Asia. Certainly camels became essential in the trade routes from southern to northern Arabia. The plaque celebrates the importance of camels in this trade which may have occurred even earlier than 3000 BC. The short-toed Snake Eagle would have been a common sight in Yemen. The sculpture features an eagle grasping a writhing serpent and may symbolize the struggle of good against evil. The last relief is a very unusual griffin. Normally a griffin is a creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion; the head and wings of an eagle; and an eagle’s talons as its front feet. Here, the front feet are a lion’s with the head of a man with lion’s ears. No idea what this means.

These statuettes sitting on patios are cubic human figures and the heads have been more carefully processed in comparison with bodies. In Timna, an ancient city in Yemen, many devotional statuettes similar to these statuettes were found in the sacred place in the cemetery. These are among the best preserved statues with boxy, human figures, a few feet high, with their forearms held out at right angles to the body. Some statues have slight, serene smiles on their faces. Therefore, it is thought that these should also be devotional statuettes. Among the best preserved statues on display are boxy, human figures, a few feet high, with their forearms held out at right angles to the body. Some statues have slight, serene smiles on their faces. They are dated to the 4th to 1st centuries BC.

[mappress mapid=”55″]

References:

Istanbul Archeology Museum: http://www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr/main_page

Pre-Islamic Arabia: http://iah211dspring2010.wikispaces.com/Group+2-1+Pre-Islamic+Arabia

Abstract Reality of Yemen: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/27/AR2005062701764.html

Eagle and Snake: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2478904/Roman-sculpture-eagle-devouring-serpent-unearthed-London.html

Felix Arabia: felix-arabia-yemen/

Southern Arabia: kingdoms-of-southern-arabia-british-museum-london/

Roads of Arabia: roads-of-arabia/