In 2004 the British Museum paired with the Bowers Museum in Southern California to present “Queen of Sheba: Legend and Reality; Treasures from the British Museum”. Curated with the British Museum from the latter’s renowned “Queen of Sheba” show in 2002, the exhibition presented the language, religion, funerary customs, and architecture of Saba. The sculpture is especially remarkable, as seen in a classically inspired second-century A.D. cast-bronze head and a sixth-century B.C. cast-bronze altar on which rows of sphinxes visually echo the dedicatory inscription in stylized Sabaean letters above them. Saba’s wealth also came from the production of frankincense; a third-century A.D. alabaster incense burner showing a camel and rider underscores its status in antiquity as an indispensable medicinal and aromatic ingredient.

This cast bronze incense burner was probably given as a dedication in the Awwam or Bar’an temple at Marib; these temples were located in the southern garden that was irrigated with water controlled by the dam. The front of the burner is decorated with the figure of an ibex, which presumably served as a handle. The ibex was sacred and was widely depicted in South Arabian art; it has been associated with rain and fertility. Almaquh, the national god of the Sabaeans, was ‘the master of the ibex’ and Sabaean rulers participated in sacred ibex hunts.

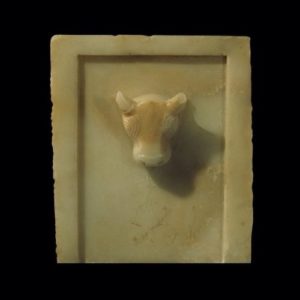

In the center of this panel is a bull’s head carved in high relief. The bull was an especially popular motif on funerary stele at Heid ibn Aqil, the cemetery at Tamna, because it was the symbol of Amm, the patron diety of the Qatabanians, who considered themselves ‘progeny of Amm’. This stela may have originally had a stone base inscribed with the name of the deceased. The Qatabanians derived great prosperity from agriculture and the incense trade but by the end of the second century AD their kingdom had declined and collapsed.

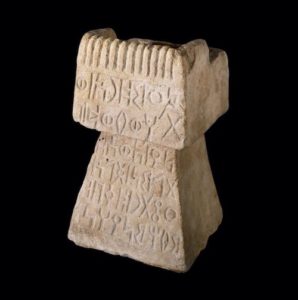

The small kingdom of Ma’in appeared in the seventh century BC. Less concerned with military exploits than their neighbors, the Mineans specialized in the incense trade with the Near East and the Mediterranean. They established close ties with other cities involved in the incense trade and often settled there; Minean inscriptions have been found as far away as Egypt and Delos. The inscription on this incense burner records the dedication of a pair of incense burners (the second one was never found) to the god Athar dhu-Qabd by Ammdhara and Hawf-Wadd. Athar dhu-Qabd (the local version of Athtar, who was worshipped throughout South Arabia) was the most important Minean diety, to whom was dedicated the great temple at the Minaean capital, Qarnaw. The kingdom of Ma’in collapsed around the beginning of the first century BC under the pressure of nomadic Arabs.

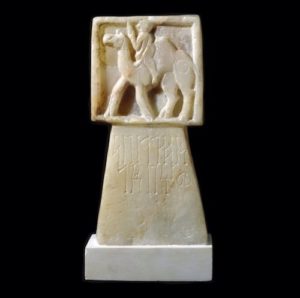

This incense burner was acquired at Shabwa by H. St J.B. Philby (1885-1960), the famous Arabian traveller and father of H.A. (Kim) Philby, the English spy. Philby visited Shabwa in 1936 during his journey from Mecca to Mukalla and described it as ‘disappointingly small and insignificant . . . with not a pillar of the sixty temples erect’. He bought eight inscriptions, later donated to the British Museum, and copied five others. The two-line Sabaean inscription implies that this incense burner was dedicated to a temple by Adhlal, son of Wahab’il. This individual is probably the one that is shown seated on the camel, with a circular shield or waterskin slung above the camel’s left rear leg.

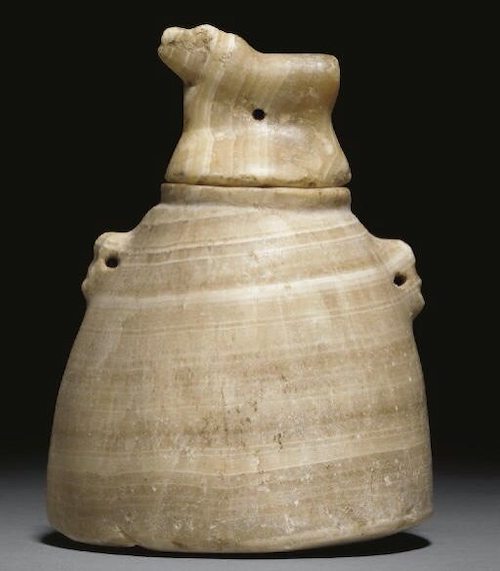

This type of calcite-alabaster jar, or so-called “beehive”-shaped vessel, has been found at archaeological sites throughout Arabia, including graves on the Persian Gulf island of Bahrain, but the majority have been found in Yemen where they were made and exported. The bottom vessel has a flat bottom, two pierced handles in the form of highly stylised bull’s heads, and two short drilled, dotted Qatabanian (or Himyaritic) inscriptions which give two personal names, “Ammyathi” and “Abkahil” in characters formed by points. The top jar has inscriptions suggesting it was made to hold perfumed oils, incense (Frankincense and/or Myrrh) or aromatic ointments such as “Balm of Gilead”. These jars must have been expensive to make and the contents would have been commensurately expensive.

Yemeni Sidr honey is produced and harvested in ways which have remained the same for centuries. The hives look similar to the beehive jars mentioned above. No chemicals or unnatural processes are ever used because this will spoil the purity of the honey. It is said that the Sidr honey from Yemen tastes better than those from other areas because the soil in Yemen is richer. Sidr is known in English as the Lote tree. It is a tree mentioned not only in Qur’an, but also the Bible and Torah. The Sidr is a very resilient tree and is mentioned many times in the Qur’an. It is said that this honey not only tastes good but has medicinal properties.

The inscription on this bronze bull from the kingdom of Himyar reads: ‘to Dhat-Himyam, two bulls’, indicating that this was one of a pair of figures to be dedicated to this god., who was associated with the sun. The bull was cast and riveted onto the double plinth base. The folds of skin around the neck and brow ridges are typical of South Arabian depictions of bulls and are also found on stone sculptures.

It is difficult to know whether gold and precious stones were exported from South Arabia in any great quantity. Archaeological evidence has recently confirmed that gold was mined in Yemen in antiquity and that the local goldsmiths were very skilled. There is also evidence for the working of precious and semi-precious stones as beads and inlays. It is rare for jewellery to survive from ancient South Arabia as it was often melted down. This gold bull’s head was made from thin raised sheet with sets of six applied granules to represent the ears, seven granules for the muzzle and applied tufts along the top of the head; the mouth is hollow. The eye stones are of circular banded agate with a pale grey lower stratum and dark brown pupil. They were set in cloisons made separately and sunk into the sheet metal. An ear of folded gold remains behind the right horn. There was a very similar gold bull head in the Muncherjee Collection, which included a large number of pieces from the Wadi Markha area.

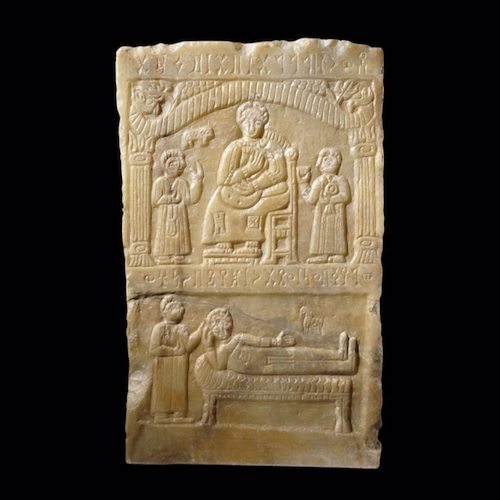

This funerary stela provides us with a rare depiction of daily life. The Sabaean inscription reads ‘Image of Ghalilat, daughter of Mafaddat and may Athtar destroy he who breaks it’. The scene appears to be a domestic one; an amply proportioned lady wearing a long dress (probably Ghalilat herself) is playing a lyre and sitting on a straight-backed chair with her feet resting on a matching stool. This figure is flanked by two girls or women, one holding a drum. On the lower register is a woman lying on an elegant couch with an attendant beside her.

This statue is of a woman in a calf-length garment, wearing heavy-soled sandals with a single thong running between the big and second toes. The remains of leather sandals have been found in burials in the South Arabian highlands which confirm the use of this type of footwear, which is also depicted on bronze statuary from Marib.

It is rare for jewelry to survive from ancient South Arabia.This gold pendant has a grooved reel at the top with thicker wire at each end that is attached to a square cloison; this holds a number of braided gold strands ending with cylindrical beads and seventeen hollow acorn-shaped buds (each made in two halves).

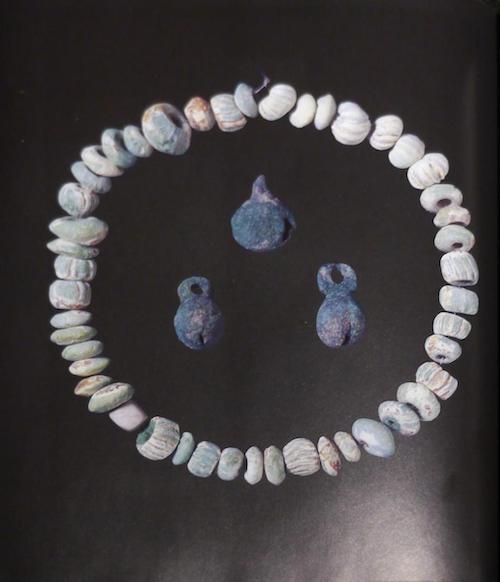

This restrung necklace of green glass melon, short bicone beads and a single marble bead was squired near Sanaa. It has been dated to the first century AD. Bells similar to these have been found in graves throughout southeast Arabia, Mesopotamia and Persia.

This statue is unusual for its careful depiction of a collar-like necklace with triangular pendants. The inlaid eyes are missing, the outstretched arms are broken and the body has been stylized to a simple cylindrical form. Another statue from Tamna has holes on either side of the neck which originally supported a necklace; an inscribed gold necklace was found nearby but it cannot be proven that this spectacular piece originally adorned the statue.

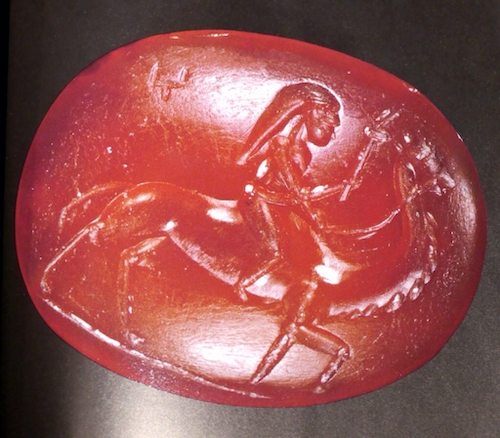

This translucent carnelian oval seal showing a man on a camel was originally set on a ring. The rider is shown riding without stirrups or saddle with a stick or “goad” in his hand. The symbol in the upper left may represent the forked lightning symbol of the god Athtar. The lack of provenance makes dating difficult, there are about 350 South Arabian seals represented in museums and collections around the world. I personally find this seal one of the most beautiful objects in this collection, it embodies the adventure most of us think of when referring to Arabia.

Several bronze oil lamps have been discovered that are decorated with an ibex, which was a popular decorative motif of the region. The animal on this example has a hole through the right foreleg which may have been used to suspend an object. It is not certain where this lamp originated, but with the lit wick floated in oil, it would have cast a beautiful light in a temple, palace or home. Furthermore, it is evidence to the existence of very skilled metallurgists in ancient South Arabia.

On this plaque is a dedication to the god Almaqah of Hirran by Yuhafri and his sons, clients of the Banu Marthadam who are described as ‘their lords’. The decoration consists of a tongue ornament along the bottom and a row of triangular decoration above the inscription with a lion standing on a pedestal in front of a palm tree.

This is the most complete ancient bronze altar to be discovered in Southern Arabia. It is thought to have been found at the Sabaean capital of Marib. It was made of bronze mixed with tin and attached to a wooden frame using small nails made of almost pure copper. Two joining portions survive. The larger consists of the front panel showing three rows of standing sphinxes set below a lightly projecting cornice around which runs the beginning of a Sabaean inscription. The inscription describes how the altar was dedicated to a local deity called Rahmaw following completion of a successful hunting trip. The name of the dedicant is not preserved. The form of the letters suggests a date in the sixth century BC.

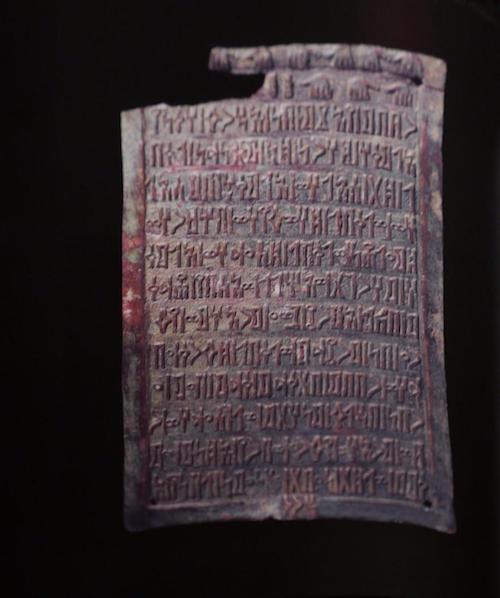

The Arabs are known to have migrated into Yemen during the 1-2nd century A.D., creating a friction recorded in a number of inscriptions between these pastoral nomads and the existing settled South Arabian communities. The top of the plaque is decorated with a row of hands which may have been intended to protect the inscription from bad fortune. The Sabaean inscription on this plaque reads:

“Rabib Yazam of the tribe Akhraf has dedicated this inscription to Almaqah of Hirran because Almaqah has demanded [it] from him in His oracle, and because he has kept him safe in his pilgrimage to dhu-Malasan, and because Almaqah has granted him trophies, spoils and captives, such as is right, on all occasions in which he to his Lord Yafra ibn Marathid, and because He has saved his servant Rabib in the battle in which he faced the Arabs in the region of Manhat (modern Hizmat Abi Thawr); and He may grant him the goodwill of his lord Yafra and the health of (his) mental and physical capacities, [and he has dedicated] for that which was for the Banu Akhraf, and will be.”

This exceptional piece is further evidence of the skill of South Arabian metalworkers. The site where it was found, Ghayman, south-east of Sanaa, has not been properly investigated, but a number of other bronze objects have been reported from here following unscientific excavations carried out before the Second World War. Interest was probably due to the tenth-century writer al-Hamdani’s description of the ‘wonderful castle [which] also is the necropolis of the famous kings of Himyar [and] should a tomb be discovered and unearthed, precious stones and money would be found therein’. The head was presented by Imam Yahya (died 1948) to King George VI (1895-1952) on the occasion of his coronation on 11 December 1936, an event which was celebrated with fires of incense on the beach at Mukalla, east of Aden.

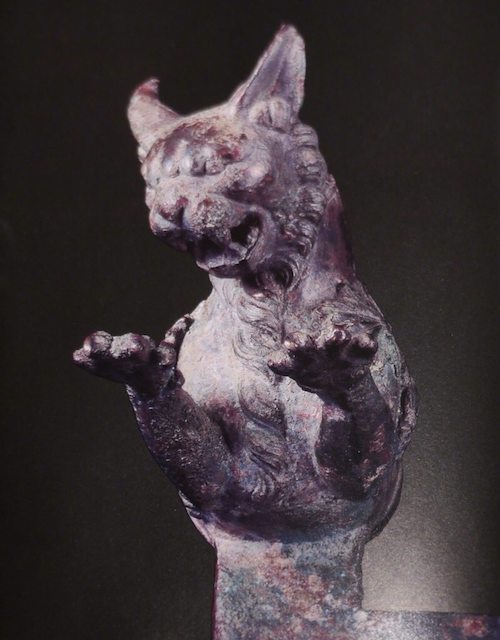

This cast bronze fitting may have originally been attached to a piece of furniture. The object was apparently originally excavated near the town of Amran and was described in 1873 in a paper by Captain WF Prideaux. The town has now been extensively rebuilt and no further archaeology in the area has been performed.

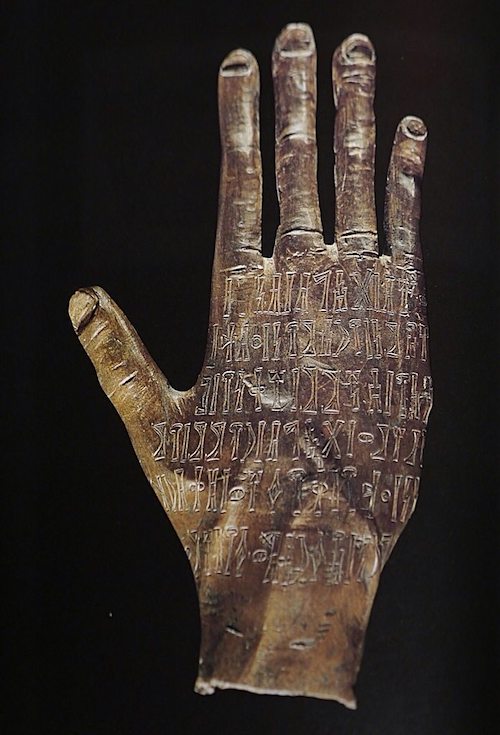

The right hand is considered a powerful sign of good fortune in Southern Arabia and was widely used as a motif in inscriptions, statues and stella. This particular example was not broken off a statue but was cast as just a hand. The inscriptions were added after casting. It is made of leaded bronze with traces of silver and nickel. This hand was dedicated to the god Talab Riyam in a place called Zafar, although this appears to be a different place than the Himyarite capital of the same name in the Yemeni Highlands. The inscription reads:

Wahabta’lab son ofHisam, [the] Yursamite, subjectof the Banu Sukhaym, has dedicated to their patron

Ta’lab Riyam this right hand

in his memorial dhu-Qabrat

in the city of Zafar, for his well being (Robin 1985)

The beginning of coin circulation in Southern Arabia can be dated to the late 5th and early 4th century BC with the arrival of the Athenian Silver TetraDrachm, and its local oriental imitations, with the owl standing on a olive twig, a crescent on the upper left and “???” in front and Athena wearing an ornamented helmet, 449 – 419 BC. According to some scholars the term balatat/balat which occurred in the last centuries BC, usually translated as coins, is an adaptation of the Greek pallav/pallavde referring in this time period to the head of the goddess Pallas Athena.

These soon were counterfeited by the kingdom of Qataban and were known locally as Qatabanian owls. The end of the 5th century saw four competing states emerge in Southern Arabia, one of them the Kingdom of Qataban, which thrived in the Baihan valley. Like most other southern Arabian kingdoms it gained its wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense. The capital of Qataban was named Timna and was located on the trade route. When the wealthy kings along the Incense Route began to mint their own coins, they imitated the most popular Athenian images.

The kings and queens of Saba also issued coins modeled after the teradrachms of Athens: with the head of the goddess Athena on the obverse and her attribute, the owl, on the reverse.

This Himyarite specimen dates from the 1st century AD and is an interesting merge of a Roman denarius and a Greek tetradrachm. The obverse shows the laureate head of the Roman emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD), while the reverse depicts the Athenian owl sitting on an amphora. The monograms on the reverse, finally, are of Arabic origin; they are of uncertain meaning.

Around the 2nd century BC the Athenian Owls were replaced with two headed coins from Qataban. The front had a beardless man with short curly hair. The reverse shows a bearded Hellenistic man with his hair in a knot behind his head. There were also monograms, symbols and letters attributed to a ruler called Yadaab. He may be identified with either Yadaab Dhubayan Yuhargib or Yadaab Dhubayan Yuhanim, both attested to be kings of Qataban. It is also believed the same king replaced the royal monogram with the name Harib, the name of his royal residence and probably also the mint.

The iconography of the Queen of Sheba’s arrival at the court of Solomon in Jerusalem was popular throughout Western Europe. However, the composition is also frequently confused with another Biblical tale set in Susa (south-west Iran) where the queen Esther requested that the Persian emperor Xerxes (who is referred to in the Bible as Ahasuerus) punish Haman for his persecution of the Jews in his name. This watch-case is a good instance of that. It was initially catalogued and published as a depiction of Sheba and Solomon but there is one crucial difference as Esther is invariably shown touching one end of the sceptre offered her by the king, as described in the Bible:

“The king was sitting on his royal throne in the hall, facing the entrance. When he saw Queen Esther standing in the court, he was pleased with her and held out to her the gold sceptre that was in his hand. So Esther approached and touched the tip of the sceptre. The the king asked, ‘What is it, Queen Esther? What is your request? Even up to half the kingdom, it will be given to you’ ” (Esther 5:3).

This was a rare and wonderful exhibition organized by The British Museum, expressly for the Bowers Museum. If you read this and want to know more, try my post on Felix Arabia, Yemen.

References:

Money Museum: http://www.moneymuseum.com/moneymuseum/coins/periods/coins.jsp?aid=2&gid=23&cid=202

British Museum: http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/online_tours/middle_east.aspx

Bowers Museum: http://www.bowers.org/index.php/art/exhibitions_details/22