A new exhibit “Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” is the first-ever comprehensive international exhibition of Saudi Arabia’s historical artifacts at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution showing Nov 17, 2012 – Feb 24, 2013. It will also travel to The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston in December 2013, Chicago and The Asian Arts Museum in 2014. Delicately crafted in repoussé to show a tight mouth, long nose and slitted eyes, the “Thaj mask” is reminiscent of the so-called Mask of Agamemnon, discovered in 1876 at the second millennium BC site of Mycenae. The Thaj mask and its companion objects are just a few of the remarkable displays in the exhibition “Roads of Arabia,” which showed at the Louvre in Paris from July to September of last year where we saw it.

With 320 objects ambitiously spanning more than a million years, from the Paleolithic to the 1932 birth of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, it turns out to be a veritable parade of virtually unknown treasures, each one a fragment of a tale from the civilizations that, over millennia, interwove their arts and their trade far more extensively than even scholars had previously believed.

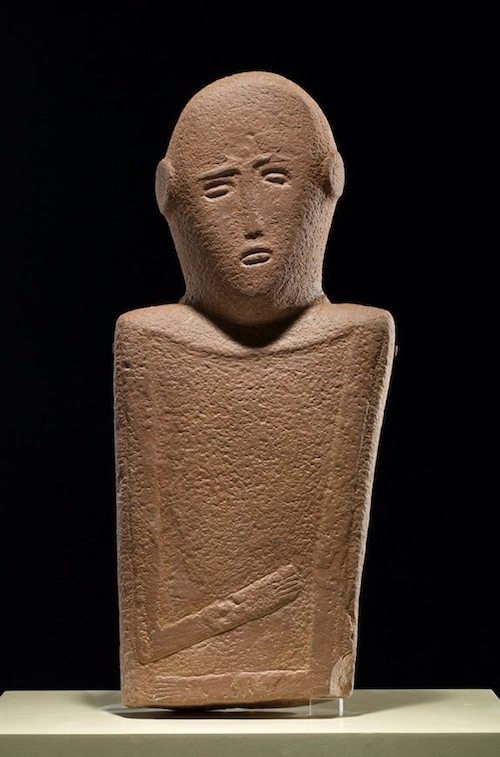

Three amazing anthropomorphic sandstone grave markers look as if they might have been crafted by an abstract sculptor of the 20th century, yet they are more than 5000 years old. This haunting anthropomorphic stele is among the earliest known works of art from the Arabian Peninsula and dates back to some six thousand years ago. Found near Ha’il in the north, it was probably associated with religious or burial practices. The figure's distinctive belted robe and double-bladed sword may have been unique to this region.

Among them, a diminutive torso with seemingly doleful eyes and a hand poignantly held over its heart stands out for its extraordinary expressiveness, achieved with a few sparely etched lines that adroitly captured the collarbone, hands and arms, quizzical mouth and odd, knob-like ears.“I dubbed him 'the suffering man,’” Beatrice André-Salvini recalls with a laugh, and the name stuck. The enigmatic character soon became a star of the show, singled out as the literal “poster boy” of the event to become a ubiquitous visual presence on banners inside the museum and on the front cover of the French edition of the catalogue. Found near Ha’il in the north-central region of the country, the statue had been erected in an open-air sanctuary, according to André-Salvini. Based on similarities to other stelae excavated in Yemen with skeletal human remains carbon-dated between 3500 and 3100 BC, she concludes that the “suffering man” was produced in the same era.

Other objects are already starting to challenge what were once historical truths. One of the show’s organizers in the United States, Sackler’s curator of Islamic art, Massumeh Farhad says, “It was practically all unfamiliar.” A carved figure of a horse, for example, includes slight ridges where the animal’s reins would have been–inconsequential except for the fact that researchers place the carving from around 7,000 BC, thousands of years prior to earliest evidence of domestication from Central Asia. Though Farhad warns more research is needed, it could be the first of several upsets. “This particular object is characteristic of the show in general,” says Farhad. “It’s new material that really sheds light on Arabia,” says Farhad, “which up to now everybody thought its history began with the coming of Islam, but suddenly you see there’s this huge chapter preceding that.” Although humans first came into contact with horses nearly 50,000 years ago, they were originally herded only for their meat, skins, and possibly for milk. The first undisputed evidence of horse domestication dates back to 2,000 BC, when horses were buried with chariots. Domestication had spread through Europe, Asia and North America by about 1,000 BC.

By the middle of the third millennium BCE, around 4500 years ago, as the Arabian Peninsula’s climate grew hotter and drier, trade emerged in the Gulf region. The exhibition showcases an abundance of objects from this period that were uncovered in 1966 on Tarut Island, on the Peninsula’s east coast, during the construction of the causeway that today links Tarut to the mainland. The hoard includes gray and black soapstone jars, bowls and fragments, many carved with snakes, leopard-like cats, lion-headed eagles and other mythic figures. In a catalogue essay, archeologist Potts contends that Tarut was the main port, and probably the capital, of the early Dilmun civilization, and that only later, around 2200 BCE, did Dilmun move south and east to the island that is today Bahrain.

Similar soapstone vessels, in what archeologists call the intercultural style, were widely traded from the Levant to Central Asia. They turn up in Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran and as far east as the Ferghana Valley in present-day Uzbekistan. Although Al-Ghabban believes that the show’s particular objects were fashioned on Tarut using local stone, other scholars, including Potts and André-Salvini, lean toward origins in southeastern Iran.

There’s no dispute, however, that the limestone statue of a man, who is probably shown praying, was sculpted on Tarut. With his clasped hands, round head, protuberant eyes and triple-belted waistband, he resembles Sumerian models from the same period around 2500 BCE. But his squarish legs and knobby knees are similar to Indus Valley effigies, too. More curiously still, at nearly a meter (39″) tall, he is the largest Mesopotamian-style statue discovered to date, notes André-Salvini—considerably larger than any unearthed in the Tigris-Euphrates region itself. The sculptor appears to have drawn from both Mesopotamian and Indus Valley examples to create his own esthetic, she says.

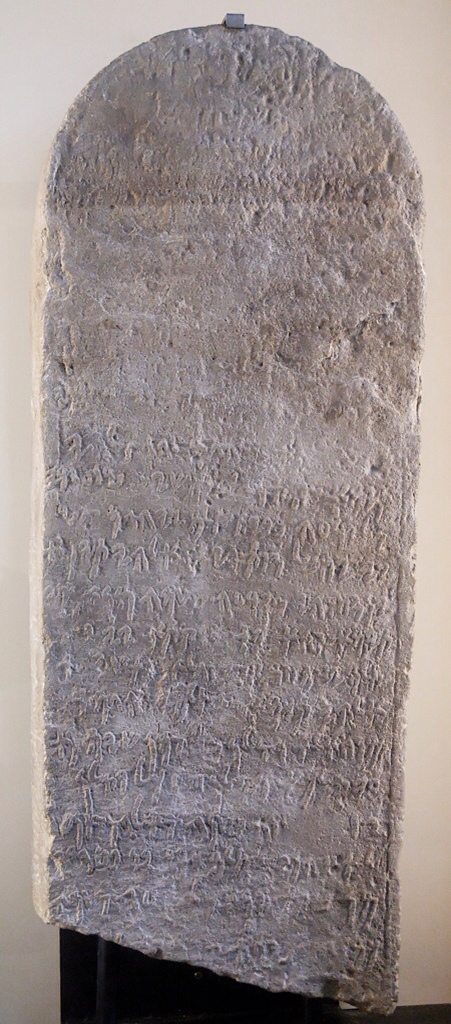

Around 1200 to 1000 BCE, the rise of camel transport revolutionized Arabian commerce. With the accompanying emergence of sprawling caravanseries, the oasis at Tayma, in the northwest of today’s Saudi Arabia, became an early, vibrant crossroad on the frankincense route from Yemen north to Mesopotamia and the Levant. Tayma’s prosperity attracted the covetous eyes of Babylonian rulers. In the sixth century BC, King Nabonidus went so far as to leave his capital city, Babylon, and occupy Tayma to control the traffic in incense, myrrh, spices, metals and precious stones.

He brought his gods with him: A weather-beaten sandstone stele shows faint depictions of the king and Babylonian deities with a cuneiform inscription about a temple dedication.

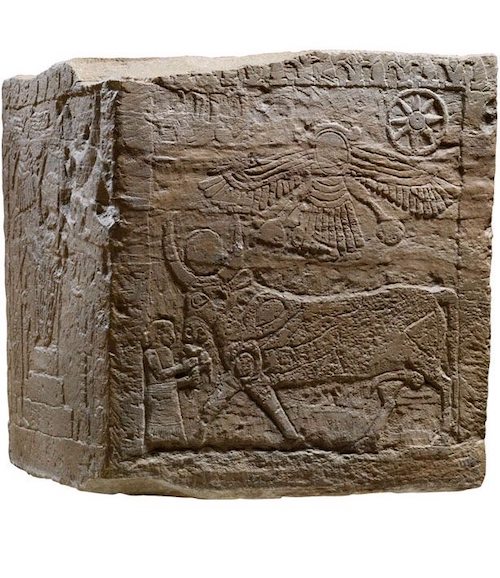

A more vivid illustration of Tayma’s patchwork of assimilated cultures is epitomized by another sculpture, the so-called “al-Hamra cube,” named for the sanctuary where it was found, and chiseled around a century after Nabonidus, in the fifth or fourth century BC. André-Salvini ticks off its syncretic elements: a “thoroughly Babylonian” priest standing before an altar to the Egyptian bull-god Apis, set against a background of winged emblems and an eight-pointed star that is probably derived from Anatolian civilization. “Despite borrowing imagery from other cultures, the art is totally unique,” she explains. “It possesses a seminal Arabic identity that’s neither Mesopotamian nor Egyptian nor Syrian.”

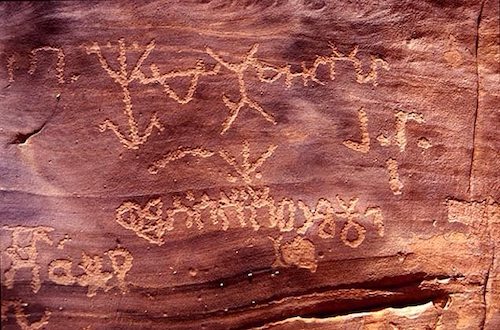

Around the same time that Nabonidus was occupying Tayma, Dedân was emerging in the fertile al-'Ula valley of fruit orchards, irrigated crops and pastures as the capital of one of the Peninsula’s least-known major ancient powers: Lihyan. Although the city’s ruins were partially excavated in the early 20th century by the French priests Antonin Jaussen and Raphaël Savignac, it is only in the past six years that archeologists from King Saud University have uncovered the full extent of a site that extends some 300 meters (960') long and 200 meters (640') wide across a rocky plain, according to Said Al-Said, the dean of the university’s faculty of tourism and archeology. Lihyan, declares Al-Ghabban, “was just as big and important as the later Nabataean kingdom, even though we know far less about it.” The first-century Roman historian, Pliny the Elder, makes only a brief reference to it when he calls the Gulf of Aqaba the “Gulf of Lihyan.” During the first millennium BC, this trade was carried on through two South Arabian peoples, the Minaeans and the Sabaeans (see my post). The Minaeans established two colonies on this route, one right in Dedân and the other in Higra, situated 15 km farther north. All the more noteworthy is the fact that the Old Testament, which has much to say about the Sabaeans, is apparently silent about the Minaeans.The Minaean colony at Dedân collapsed at the same time that the motherland was subjugated by the Sabaeans. This event cannot be dated precisely; it appears to have happened at the beginning of the second century BC.

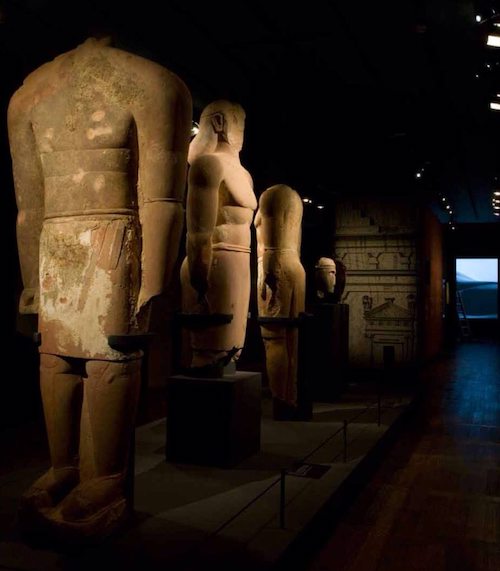

Among the spectacular Lihyanite finds of the King Saud University team are three colossal red sandstone statues, unearthed in 2007 near the Kuraybah temple sanctuary north of al-'Ula. Depicting kings, each of the statues in the “Roads” exhibition stands more than two meters (6'5″) tall. With stiff arms held close to their sides, the figures strike heiratic poses that hark back to Egyptian models. But the naturalistic depiction of their muscular torsos points to Greek influence. While inventing their own hybrid school of art, the Lihyanite sculptors drew inspiration from their Egyptian and Greek predecessors.

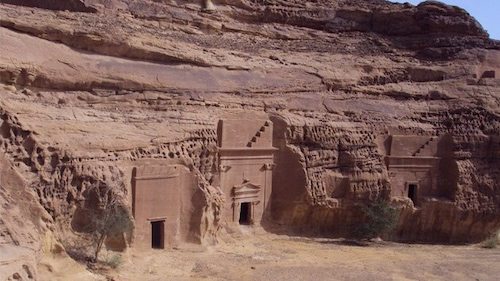

By the first century CE, Mada’in Salih, 22 kilometers (35 mi) north of al-'Ula, became the southern outpost of the Nabataean kingdom and its center for domination of the Arabian caravan routes. The exhibition continues with photographs of elaborate Nabataean tombs cut into honey-hued cliffs and crags. The tomb façades show an eclectic mix of Egyptian cornices, Assyrian bas-relief crenellations and Greco-Roman triangular tympanums. The Romans occupied the region in the early second century, and a stone plaque, unearthed in 2003 by archeologist Daifallah Al-Talhi, attests to the restoration of the city’s ramparts during the reign of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. One of the rare Latin inscriptions found in the Arabian Peninsula, the text credits the local citizens for paying the Roman legionnaires ordered to carry out the construction.

Some 1000 kilometers (620 mi) south of Mada’in Salih, on the western edge of the Rub’ al-Khali (“Empty Quarter”) desert, there thrived another commercial hub, Qaryat al-Faw. For more than 600 years, from the third century BC to the fourth century CE, it was an oasis of red-clay palaces, temples, markets, an extensive necropolis and at least 120 wells. This bronze head was originally part of a life-sized statue. Although partially damaged, the face is visibly treated in a Greco-Roman style, while the thick curls are typical of local workmanship. During the first and second centuries CE, southern Arabia enjoyed strong commercial contacts with the Mediterranean world and the Roman Empire, which is also apparent in the arts and material culture of the period.

It was a city of farmers and herders of sheep, cattle and camels that became “a staging point for travelers, merchants and pilgrims from the different kingdoms of Arabia,” according to Abdulrahman Al-Ansari, the veteran archeologist, in charge of excavations there from 1971 until 1995, who wrote about Qaryat al-Faw for the exhibition catalog. As the capital of the Kinda kingdom, Qaryat al-Faw was, he wrote, “an economic, religious, political and cultural center at the heart of the peninsula.” The small exceptional statue of the Greek hero Heracles is identifiable by his lion skin and club. Originally, he would have held a drinking vessel in his right hand, an attribute of Heracles-Bibax or the drinking Heracles. This form of Heracles was associated with Dionysus, the Greek god of banqueting and wine, whose cult was popular in Qaryat al-Faw. I would just like to interject that the number of bronze statues from this time period are vanishingly small, this is indeed a rare piece of art.

Just for comparison, these are the Heracles from Rome. The guilded bronze Hercules of the Forum Boarium is on the left from the Capotoline Museum in Rome. The figure of Hercules bears his club at the ready, and in his left hand holds the three apples of the Hesperides. The apples identify him specifically as a Hercules of the West, where he was the victor over Geryon. The sculpture on the right is the Lysippic gilded bronze that was discovered in 1864 near the Theatre of Pompey, the Hercules of the Theatre of Pompey from the Vatican. The figure supports himself lightly on the vertically-stood club; the skin of the Nemean Lion is draped over his left forearm. Both sculptures display the contrapposto typical of Lysippic manner, in which the figure's weight is thrown entirely on one foot.

The musculature of the Qaryat al-Faw Hercules is more like the famous Farnese Hercules made in the early third century AD and signed by a certain Glykon, from an original by Lysippos (or one of his circle) that would have been made in the fourth century BC. The Qaryat al-Faw Hercules must have been made by someone familiar with Lysippos, and yet represents an entirely new representation of the subject. The resultant bronze is both invaluable and intriguing as it relates to the original inspiration.

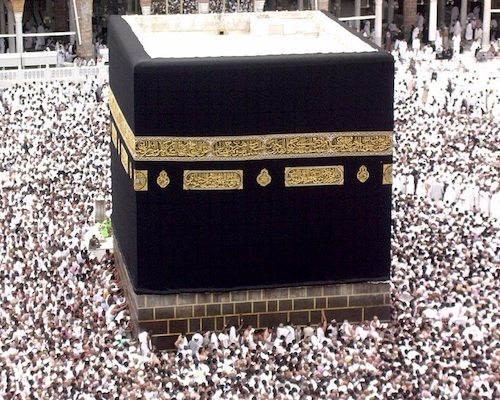

From Najram, this bronze lions head and paw were found in the 1930's by the explorer and writer Abdullah Philby, the the father of the British agent Kim Philby. He presented it to King Abdul Aziz. Najran was the Yemeni centre of cloth making and originally, the kiswah or the cloth of the Ka'aba was made there (the clothing of the Kaba first started by the Yemeni kings of Saba). There used to be a Jewish community at Najran, renowned for the garments they manufactured. According to Yemenite Jewish tradition, the Jews of Najran traced their origin to the Ten Tribes. Najran was also an important stopping place on the Incense Route.

Dating back to the early years of Islam, the countless tombstones in Mecca attest to the immense hardships endured by pilgrims. At the same time, they lend a human face to the multitude of devout visitors to the holy site. Most of the tombstones are hewn out of simple, irregular blocks of stone and the inscriptions are fitted to the size and shape of the surface. Although the stonemasons must have worked with simple tools, they succeeded in achieving an astounding range and variety of highly original formats and scripts.

Commissioned by the mother of the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV (reigned 1623-40), this exquisite incense burner is one of the many gifts presented to the shrine at Mecca, the spiritual center of Islam. The elegantly designed object also attests to the continued importance of incense in the Islamic world.

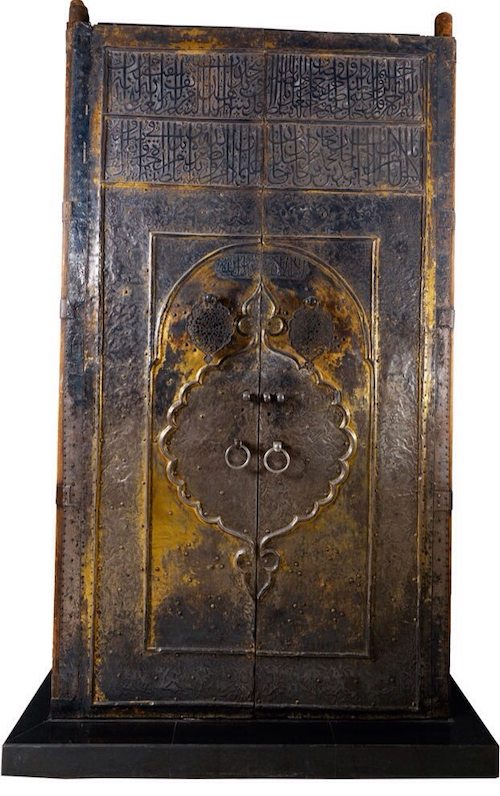

This massive wooden door, covered with silver leaf, was donated to Mecca by the Ottoman sultan Murad IV (reigned 1623-40) and formerly stood at the entrance to the interior of the Ka‘ba. Primary sources suggest that the design of such doors changed little over the centuries. A tenth-century poet relates that the door at that time was “covered with inscriptions, circles and arabesques in gilded silver.” The Ottoman door was used until around 1947.

I feel that a little editorial comment is in order here. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has been described as a tough regime but equally as an oasis of stability in an unstable region. The early Arabian population consisted primarily of warring nomadic tribes. When they did converge peacefully, it was usually under the protection of religious practices. The Saudis are a strict sect of Sunni Muslims, which is something I did not know. The officially approved form of Islam in Saudi Arabia, Wahhabism, is hostile to any reverence given to historical or religious places of significance for fear that it may give rise to idolatry. As a consequence, under Saudi rule, it has been estimated that since 1985 about 95% of Mecca's historic buildings, most over a thousand years old, have been demolished. Thus it is remarkable and encouraging that the Kingdom has not only authorized archeology of its pre-Islamic past but has commissioned this exhibition. This a rare and unprecedented look into the history of one of the most important areas of the planet, and well worth visiting. If you have read this post, consider reading my companion post “The Incense Road“.

References:

Roads of Arabia: http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/201102/roads.of.arabia.htm

Smithsonian: http://www.roadsofarabia.com/plan-your-visit/index.html

Louvre Exhibition: http://www.france24.com/en/20100721-roads-arabia-lead-louvre-museum-exhibition-paris-france-saudi-arabia-undiscovered

Archeology Sites in Saudi Arabia: http://nabataea.net/saudi.html

Total Foundation: http://foundation.total.com/exhibition-roads-of-arabia-archeological-treasures-from-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia-503128.html&projectMedia=1426#mediaBloc

Roads of Arabia: http://www.scta.gov.sa/Antiquities-Museums/ArcheologicalMasterpieces/Documents/Routes_d_Arabie_ar.pdf

Roads of Arabia Brochure: http://www.us-sabc.org/files/public/Roads_of_Arabia_Brochure.pdf

Roads of Arabia Universe: http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/specials/2012/roads_of_arabia/photos/07#imgNav

Hindustan Times: http://www.hindustantimes.com/photos-news/Photos-World/jan26exhibition/Article4-802462.aspx