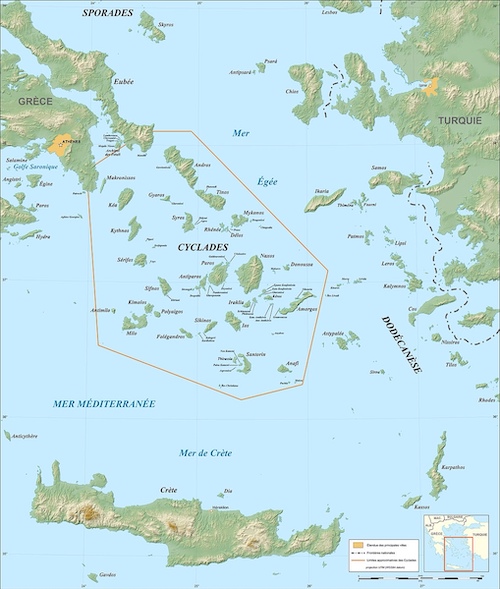

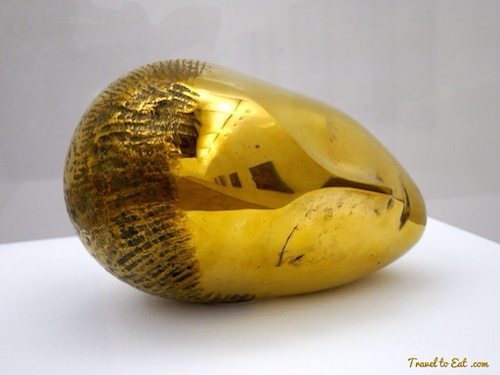

When we visited the Getty Villa, I was particularly drawn to the Cycladic exhibition of figures and pottery, not only for their artistic merit but also for their age and impact on the Mediterranean world. The Cyclades are an island chain between Greece and Turkey and north of Crete. Along with the Minoans and Mycenaeans, the Cycladic people are counted among the three major Aegean cultures. Cycladic Sculpture therefore comprises one of the three main branches of Aegean art. The first archaeological excavations of the 1880s were followed by systematic work by the British School at Athens and by Christos Tsountas, who investigated burial sites on several islands in 1898-99 and coined the term “Cycladic Civilization”. Interest then lagged, but picked up in the mid-20th century, as collectors competed for the modern-looking figures that seemed so similar to sculpture by Jean Arp or Constantin Brâncuși. Sites were looted and a brisk trade in forgeries arose. The context for many of these Cycladic Figurines has thus been mostly destroyed; their meaning may never be completely understood. What is known is that they were often painted, possibly used as idols and were often included in grave goods. They date to the second and third millennia BCE (3300-2000 BCE), end of the Neolithic and beginning of the Bronze Age.

The islands are located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia Minor and the Near East as well as between Europe and Africa. In antiquity, when navigation relied on dead reckoning and/or cabotage and sailors sought never to lose sight of land, they played an essential role as a stopover. Obsidian originating from Milos has been discovered in the Franchthi cave, on mainland Greece, in a strata from the 11th millennium, indicating seafaring trade from at least that time period. The inhabitants of these islands, who lived mainly near the shore, were remarkable sailors and merchants, thanks to their islands’ geographic position. A distinctive Neolithic culture amalgamating Anatolian and mainland Greek elements arose in the western Aegean before 4000 BCE, based on emmer wheat and wild-type barley, sheep and goats, pigs, and tuna that were apparently speared from small boats. Excavated sites include Saliagos and Kephala (on Keos) with signs of copper-working. It seems that at the time, the Cyclades exported more merchandise than they imported. Many of the Cycladic Islands are particularly rich in mineral resources, iron ores, copper, lead ores, gold, silver, emery, obsidian, and marble, the marble of Paros and Naxos among the finest in the world. They were blessed with natural resources, obsidian from Milos, copper, silver, marble and pigments. Tools were used to work marble, above all coming from Naxos and Paros, either for the celebrated Cycladic idols, or for marble vases. It appears that marble was not then, like today, extracted from mines, but was quarried in great quantities. The emery of Naxos also furnished material for polishing and the pumice stone of Santorini allowed for a perfect finish. The pigments that can be found on statuettes, as well as in tombs, also originated on the islands, as well as the azurite for blue and the iron ore for red.

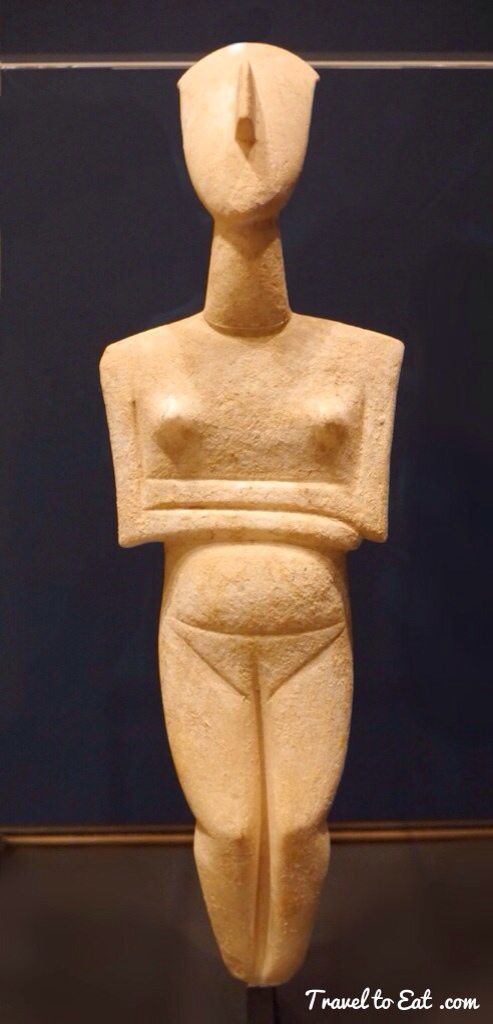

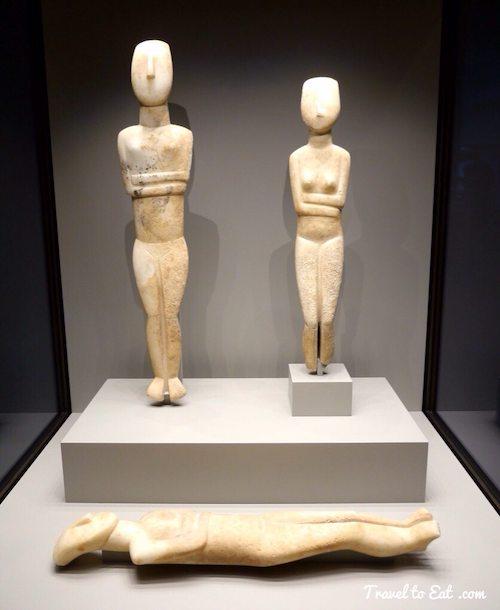

These marble figures were carved before the representation of females became standardized in Cycladic sculpture. Note how differently the faces are rendered. One figure has its eyes and nose carved in relief, but not its mouth. A hole in its right thigh indicates that its leg was broken off and rejoined in antiquity. Only the tall figure with fully developed folded arms has much attention given to such details as the pupils, fingers, and navel. The arms are however, unnaturally short. The small figure has truncated limbs and no facial features.

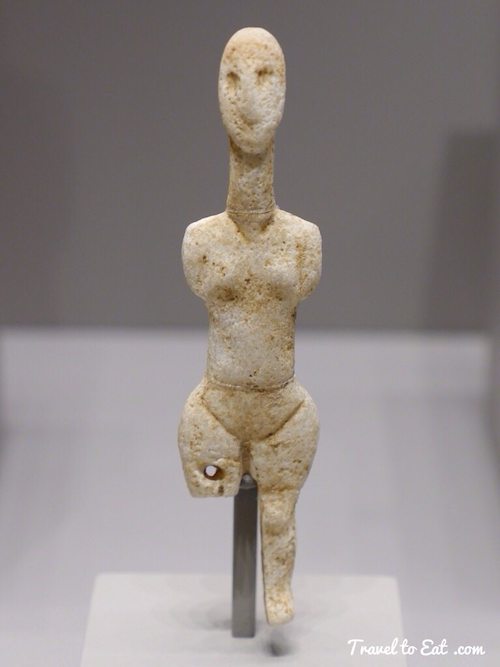

In this almost complete female figure (without feet), we see the full stylistic representation of a woman. She has the face with only a nose, an exagerated neck, stylized breasts, folded arms without hand detail and a pubic triangle. In addition, this figure shows an exagerated stomach, possibly inferring that this is a fertility symbol.

Cycladic female figures have been interpreted in a variety of ways. While some scholars have suggested that they represent concubines meant to accompany deceased males to their graves, others believe they depict ritual dancers. It is also possible that they are images of a goddess or symbols of fertility. By about 2700 BC, the folded-arm figure had become the standard form for female sculpture in the Cyclades. Most of the figures cannot stand upright; their feet are bent, and their toes point downward. They were probably intended to lie on their backs, as their folded arms suggest repose. The slight bend of the knees and the arched shape of the head, however, seem to contradict a comfortable reclining position, or they were using pillows. The reclining statue displayed here is one of the best-preserved figures in the Museum’s collection. What is left of its pigment indicates the ears, the mouth, and a fringe of hair on the forehead,as well as makeup or dotted tattoos on the cheeks. Painted lines also appear under the chin and at the top of the spine. Despite these general similarities it is, however, important to note that no two figurines are exactly alike, even when evidence suggests they come from the same workshop.

On this particularly large head, you can see traces of tattooed pigment and the stylized head with only the nose in relief.

The vast majority of Cycladic sculptures represent standing or reclining female figures. Only five percent of the figures are males; unlike the females, most males are depicted doing something, often playing an instrument. Fewer than a dozen of these male harpists are known, and this example is by far the largest. This harp player, seated on a four legged stool, is also unusual in that, unlike the others, he does not actually play his harp; he merely holds it, resting its soundbox on his thigh. On the top of the harp is an ornament carved in the shape of the head of a waterfowl or snake. The harpist sculptures provide a historical record relative to the existence of music and instruments that Cycladic peoples had and clearly valued. Found primarily in graves, it is interesting to note the synchronicity between these harpists and the lyres found in Mesopotamian tombs dating to roughly the same time. There is no evidence as of yet that the two societies knew about each other or their similar taste in music or instruments relating to funerary practices.

The use of such a hard material and consequently the time needed to produce these pieces would suggest that they were of great significance in Cycladic culture but their exact purpose is unknown. Their most likely function is as some sort of religious idol and the predominance of female figures, sometimes pregnant, suggests a fertility deity. Supporting this view is the fact that figurines have been found outside of a burial context at settlements on Melos, Kea and Thera. Alternatively, precisely because the majority of figures have been found in graves, perhaps they were guardians to or representations of the deceased. The examples above show the spread of stylized female figures across the Mediterranean, to Turkey, Greece, Cyprus and even Portugal. There must have been a powerful message that accompanied these statues although we have yet to decipher their meaning.

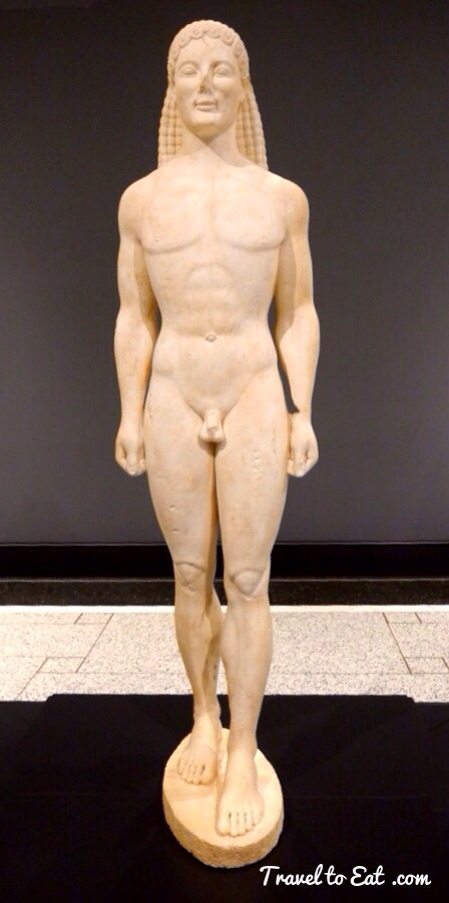

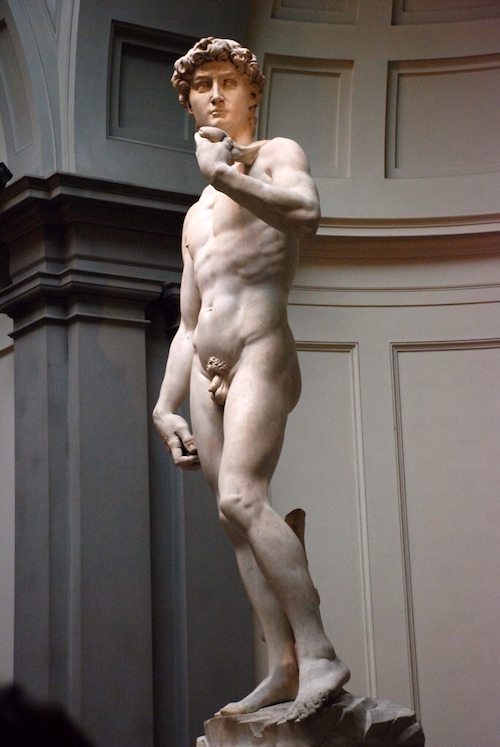

Abstraction is a reality of modern art due to the pervasive influence of photography and even more recently, 3-D printing. Abstraction has many expressions, from the stoic animal morphed human statues of the Egyptians to the Greek Kourous to Michelangelo’s David with his exaggerated musculature and huge hands. Somehow, we have this innate feeling of superiority over ancient civilizations but we must remember that the 10,000 years separating us from the Neolithic revolution is a tiny slice in human history. Our forefathers were just as intelligent, just as capable as artists as we find ourselves today. I once thought that Egyptian and Assyrian artists were not as evolved as the Greeks and later the Romans. I now believe that art is an expression of civilization, that the product is hard to quantify, even harder to criticize, art is a package deal with literature, poetry, music, civilization and war. I hope you liked this subject as much as I did.

References:

Met Cyclades: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ecyc/hd_ecyc.htm

Getty Villa Harp Player: http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=12928

Met Museum Harp Player: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/47.100.1

Queen Pu-Abi Burial: /queen-pu-abi-of-ur-british-museum-london/

Chariots, the First Wheels of War: /chariots-the-first-wheels-of-war/

Ancient History Encyclopedia: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/457/