I recently visited the British Museum and found some beautiful pieces and the history accompanying them that I found very interesting. I am also providing a bit of background regarding the location of the tomb in which these artifacts were discovered. Pu-abi (Akkadian: “Word of my father”), also called Shubad due to a misinterpretation by Sir Charles Leonard Woolley, was an important person in the Sumerian city of Ur, during the First Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2600 BCE). Commonly labeled as a “queen”, her status is somewhat in dispute. Several cylinder seals in her tomb identify her by the title “nin” or “eresh”, a Sumerian word which can denote a queen or a priestess. The fact that Pu-abi, herself a Semitic Akkadian, was an important figure among Sumerians, indicates a high degree of cultural exchange and influence between the ancient Sumerians and their Semitic neighbors.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of an early occupation at Ur and Eridu during the Ubaid period (6500-3800 BC). These early levels were sealed off (the first layers) with a sterile deposit of clay and soil that was interpreted by excavators of the 1920s as evidence for the Great Flood of the book of Genesis and Epic of Gilgamesh. It is now understood that the South Mesopotamian plain was exposed to regular floods from the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, with heavy erosion from water and wind, which may have given rise to the Mesopotamian and derivative Biblical Great Flood beliefs. The Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BC) existed from the protohistoric Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age period in the history of Mesopotamia, following the Ubaid period and succeeded by the Jemdet Nasr period. During the Ubaid period, Ur was a seaside resort. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia. It was followed by the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries) saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it may also be called the Protoliterate period. It was during this period that pottery painting declined as copper started to become popular, along with cylinder seals. The further occupation of Ur only becomes clear during its emergence in the third millennium BC (although it must already have been a growing urban center during the fourth millennium). The third millennium BC is generally described as the Early Bronze Age of Mesopotamia, which ends approximately after the demise of the Third Dynasty of Ur in the 21st century BC.

The city of Ur lost its political power after the demise of the Third Dynasty of Ur in the 21st century BC. Nevertheless, its important position which kept on providing access to the Persian Gulf ensured the ongoing economic importance of the city during the second millennium BC. The splendor of the city, the might of the empire, the greatness of King Shulgi, and undoubtedly the efficient propaganda of the state endured throughout Mesopotamian history. Shulgi was a well known historical figure for at least another 2,000 years, while historical narratives of the Mesopotamian societies of Assyria and Babylonia kept names, events, and mythologies in remembrance. Before Akkad was identified in Mesopotamian cuneiform texts, the city was only known from a single reference in Genesis 10:10 where it is written אַכַּד (Accad). The city of Akkad is mentioned more than 160 times in cuneiform sources ranging in date from the Akkadian period itself (2350–2170 or 2230–2050 BCE, according to respectively the Middle or Short Chronology) to the 6th century BCE. The location of Akkad is unknown but throughout the years scholars made several proposals. Whereas many older proposals put Akkad on the Euphrates, more recent discussions conclude that a location on the Tigris is more likely.

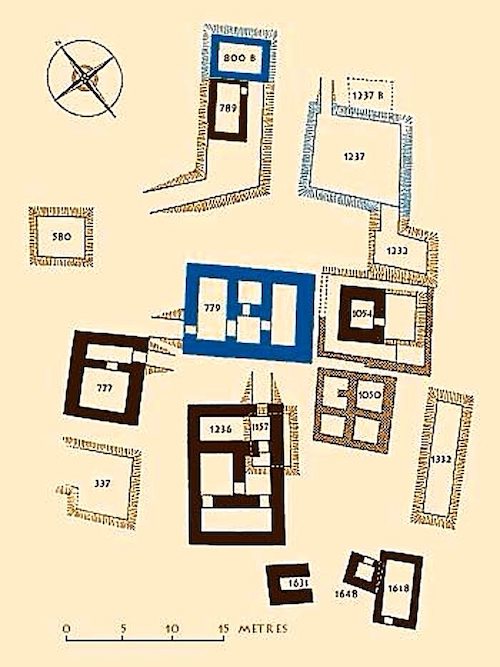

The cemetery was originally dug outside the walls of the city of Ur, not far from the temple buildings and was built over by the walls of Nebuchadnezzar's larger city about 2,000 years later. Some 1,840 burials were found, dating to between 2600 BC and 2000 BC. They ranged from simple burials (with a body rolled in a mat) to elaborate burials in domed tombs reached by descending ramps. Sixteen of the early burials Woolley called 'Royal Graves' because of the rich grave-goods, the presence of burial chambers, and the bodies of the attendants who had apparently been sacrificed.

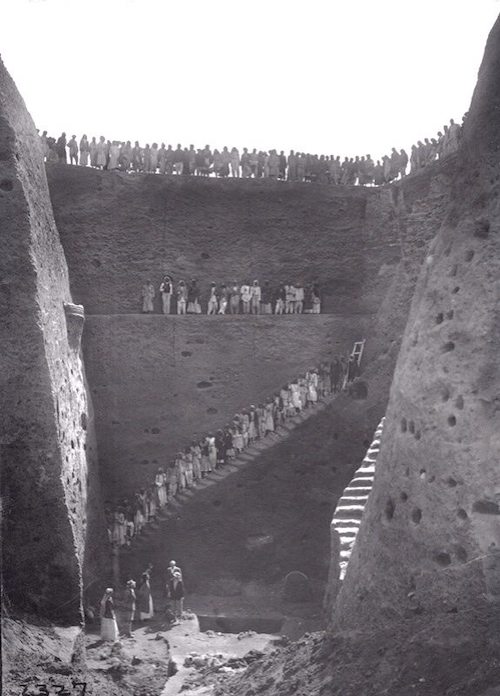

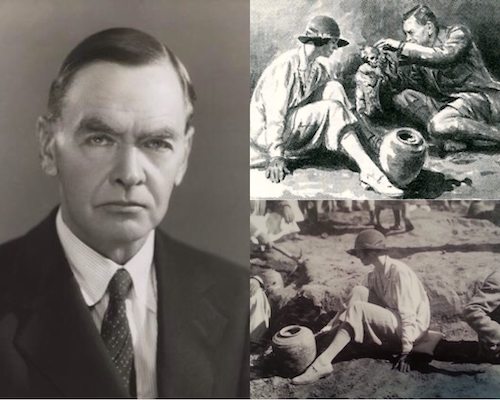

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, a rubbish dump built up over centuries. Unable to use the area for building, the people of Ur started to bury their dead there. The cemetery was used between about 2600-2000 BC and hundreds of burials were made in pits. Many of these contained very rich materials. In one area of the cemetery a group of 16 graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. You can see how deep the pit could be from the above photo of Woolley at the excavation. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to 74 such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley, thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

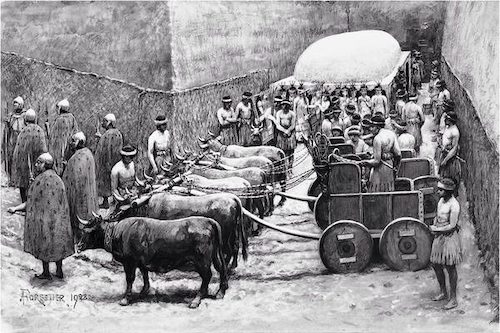

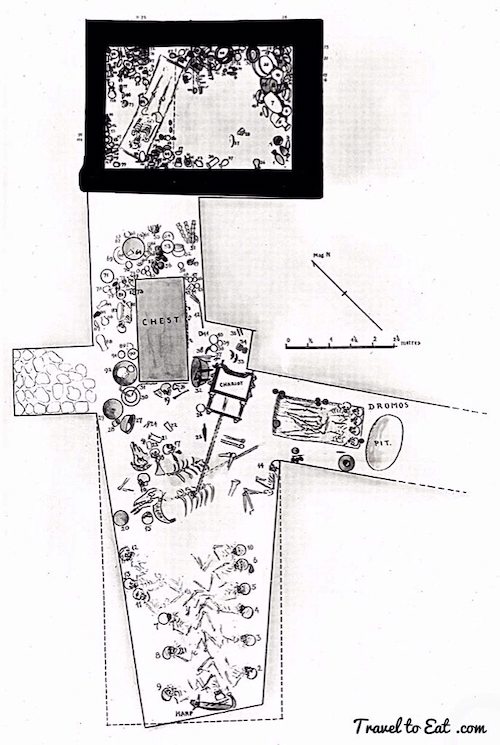

The attendants were arranged as shown, then they were given poison to drink. The oxen were also killed. The structure in the background is the domed burial chamber. The female attendants, with their elaborate headdresses, are lined up before it. The men on the left are the soldiers who will guard the tomb for all eternity.

The tomb (PG800), measuring 4.35 x 2.8 meters, was a vaulted chamber that was built of limestone slabs and mud brick and placed on top of a raised wooden platform was a skeleton of a middle aged woman about 40 years old. According to written descriptions of the site, the woman was decorated in elaborate gold, lapis lazuli, and a carnelian headdress. Also discovered on the body were a pair of crescent-shaped gold earrings and covering the entire torso of the skeleton were gold and semi-precious beads. The royal cemetery tomb of Queen “Pu-abi” at Ur, like the tomb of King Tutankhamun of Egypt, was an especially extraordinary find, because it was intact and had escaped looting throughout the millennia.

In addition to the precious artifacts, many other skeletons were distributed throughout the site. A total of 52 other skeletons were found, in addition to the middle aged women on the raised slab. Taking into account all the precious artifacts and the immense amount of skeletons buried with the woman, it is theorized that this woman, Pu-abi, was royalty during the dynasty of Ur and those were her servants. A sudy was recently done at the UPenn Museum on the skulls of a woman and a soldier. Both skulls show signs of premortem fractures, the kind of fracture caused by a blunt weapon. This was deemed to be the cause of death, not poisoning. The two theories, death by poison and death by blunt force trauma, are not incompatible. It suggests that the participants whose dosage of poison had not proved to be fatal were given a coup de grâce to spare them prolonged suffering and to insure that they wouldn't be buried while still alive and conscious. Sort of gross but it is what it is.

Near Pu-abi's right shoulder, three lapis lazuli cylinder seals were found. These cylinder seals were discovered in the 'Queen's Grave' in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. Both of the above seals are engraved with banquet scenes. It has been suggested that this indicates that the owner was female, while a man's seal would have been engraved with a combat scene. Indeed, the cuneiform inscription on the bottom seal reads 'Pu-abi nin'. The Sumerian word 'nin' can be translated as either 'lady' or 'queen'. It is possible that Pu-abi (previously read as Shub-ad) may have been a high priestess in the service of the moon god, Nanna, patron of Ur. The seal is made from lapis lazuli, which would have come from Afghanistan. This not only shows the extensive trade routes that existed at this time, but also how important Pu-abi was, owning an object made of such an exotic material.

Queen Pu-abi wore an elaborate headdress of gold leaves, gold ribbons, strands of lapis lazuli and carnelian beads, a tall comb of gold, chokers, necklaces, and a pair of large, crescent-shaped earrings. Her upper body was covered in strings of beads made of precious metals and semi-precious stones stretching from her shoulders to her belt, while ten rings decorated all her fingers. An ornate diadem of thousands of small lapis lazuli beads with gold pendants of animals and plants was on a table near her head. Two attendants were buried in the chamber with her; one crouched at her head, the other at her feet. Shell, used for cosmetics cases, pouring vessels, and cylinder seals, came from the Persian Gulf. Carnelian, a semi-precious stone used extensively for beads, came from eastern Iran and/or Gujarat in India. Lapis lazuli was used for jewelry, cylinder seals, and inlays, and came from northeastern Afghanistan. Mentioned in Mesopotamian myths and hymns as a material worthy of kings and gods, lapis would arrive in small, unfinished chunks to be worked locally into beads, cylinder seals, or inlays. Similar beads of agate and jasper came from Iran’s mountains and plateau. The Sumerians, more than any other people in the world, loved lapis lazuli. For them, it represented fabulous wealth, literally and as well as figuratively. It is not indigenous to Sumer, and was mined in faraway Afghanistan. Because it had to be imported over vast distances, it was very expensive. Kim Benzel believes that the collection is not only expensive but sacred, both for the materials and for the religious process of manufacture. This mid-third millennium B.C. assemblage represents one of the earliest and richest collections of gold and precious stones from antiquity and figures as one of the most renowned and often illustrated aspects of Sumerian culture.

The excavated treasures from Woolley's expedition were divided between the British Museum in London, the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the National Museum in Baghdad. Several pieces were looted from the National Museum in the aftermath of the Second Gulf War in 2003. Recently, in 2000, several of the more spectacular pieces from Pu-abi's grave have been the feature of a highly successful Art and History Museum tour through the United Kingdom and America. In this post I am going to focus on the pieces in the British Museum and I present the above items just to give you an idea of the University of Pennsylvania Museum presentation, where the majority of the personal jewelry of Pu-ali ended up, which I hope to visit in the future. The gold ornamentations of the diadem were originally labeled as “stalks of grain”, but were later identified as apples and the male and female flowers of the date palm, all of which are believed to be symbols of fertility.

The Sumerians believed it was necessary to bring gifts (bribes) for the gods and goddesses of the underworld to insure the deceased had a comfortable stay in the afterlife. For instance, King Ur-Namma made sure to bring many expensive gifts for the deities of the netherworld. This is the reason why many feminine articles (jewelry) were found in the graves of men, and many masculine articles (daggers) were found in the graves of women. Even the attendants were given fine jewelry for the afterlife.

The bowl was found very close to Pu-abi. It is made from beaten gold with small tubes of gold attached to the sides by brazing (or hard-soldering). Through these lugs, two strands of gold wire, twisted to give a cable effect, have been threaded to form a handle. The excavator Leonard Woolley found a silver tube inside the bowl, which may have been a drinking straw. Each of these vessels is unique and utilizes a special use of gold. Even the unseen bottoms are decorated. There are no deposits of gold in Mesopotamia, and the metal would probably have been imported from Iran or Anatolia (modern Turkey). However, these vessels were almost certainly manufactured in Mesopotamia.

This goblet comes from the Queen's Grave in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. It was one of four vessels (including a gold cup) found together on the floor of the pit where most of the sacrificial victims lay. The vessel is made not of gold but electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold). It contains green eye paint like the gold imitation shells found in 'Queen' Pu-abi's tomb chamber. The upper part is made of a double layer of metal and the foot is joined to the bowl by brazing (hard-soldering).

Leonard Woolley discovered several lyres in the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. These were the two that he found in the grave of 'Queen' Pu-abi. The front panels are made of lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone originally set in bitumen. The gold mask of the bull decorating the front of the sounding box had been crushed and had to be restored. While the horns from the British Museum are modern, the beard, hair and eyes are original and made of lapis lazuli.

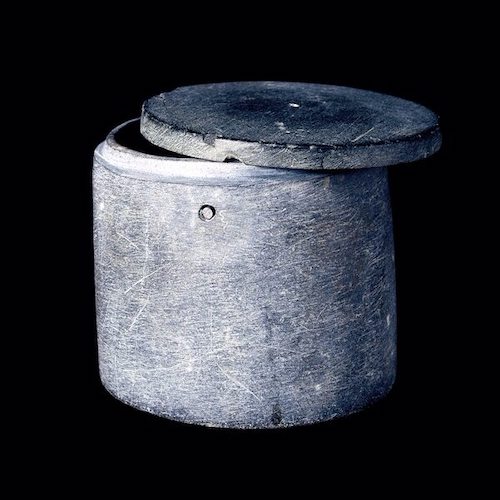

This stone jar was found in the tomb of 'Queen' Pu-abi, one of the best preserved in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. The four holes through the sides of the jar below the rim are roughly equidistant, and may have been for securing the lid with strings through the hole in the middle of the lid.

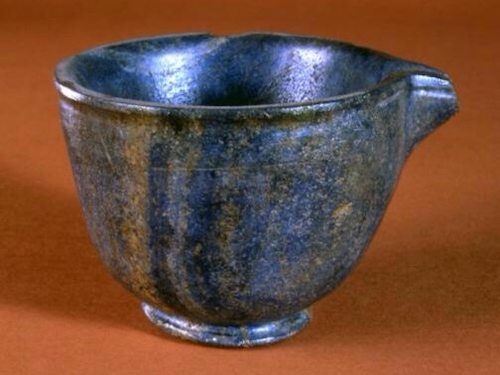

This cup carved from lapis lazuli must have been fabulously expensive, considering that the stone was from Afghanistan. Perhaps it was considered a sacred object and was buried with the priestess.

The royal cemetery excavations of that early era in archaeology remain one of the most remarkable technical achievements of Near Eastern archaeology, and they helped to catapult Sir Charles Leonard Woolley’s career. Indeed, at the time of its discovery, the royal cemetery at Ur competed only with Howard Carter’s discovery of the intact tomb of the boy pharaoh Tutankhamun for public attention. By the end of the excavation in 1934, Woolley had become, as the Illustrated London News termed him, “a famous archaeologist,” with his own series on BBC Radio, and in a little more than a year he was awarded knighthood. His archaeological career was interrupted by the United Kingdom's entry into World War II, and he became part of the “Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section” of the Allied armies made famous in the movie “Monuments Men”. His wife Katherine died in 1945. One of Sir Leonard Woolley's colleagues, archaeologist Max Mallowan, met the detective novelist Agatha Christie at the excavations of Sir Leonard Woolley. Mallowan later married Agatha Christie, and her book Murder in Mesopotamia is based on her experiences at the excavations at Ur. The murder victim in the Agatha Christie's detective is Katherine Woolley, Sir Leonard's wife.

References:

I do not often recommend a specific site for more information, but in this case I make an exception. Jerald Jack Starr from Nashville has created an exceptional website, Sumerian Shakespeare, which you should visit if you have an interest in Sumeria.

Penn Museum: http://www.penn.museum/sites/iraq/?page_id=28

British Museum: http://www.britishmuseum.org/search_results.aspx?searchText=Pu-abi&searchPrevious=Puabi&tPage=1

Sumarian Shakespeare: http://sumerianshakespeare.com

Cause of Death of Attendants: http://www.penn.museum/sites/iraq/?page_id=233

Elizabeth Smith: http://elizabethjsmithart.blogspot.com/2009/09/rare-books-tour-phila-free.html

Royal Tombs of Ur: http://sumerianshakespeare.com/117701/117801.html

Puabi's Jewelry, Kim Benzel: http://academiccommons.columbia.edu/download/fedora_content/download/ac:162298/CONTENT/Benzel_columbia_0054D_11436.pdf

Open Context: http://opencontext.org/subjects/GHF1SPA0000077950