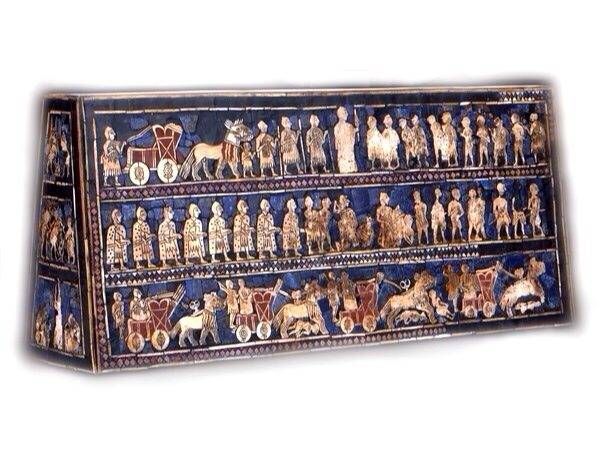

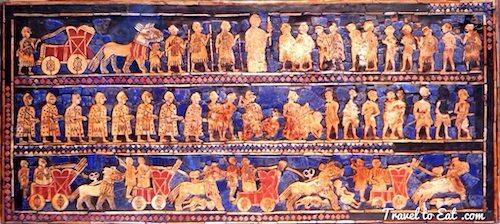

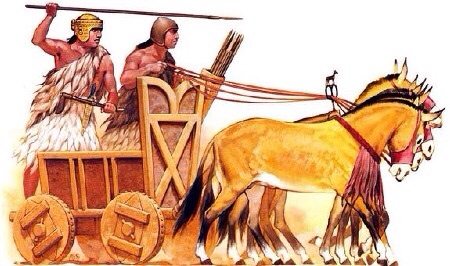

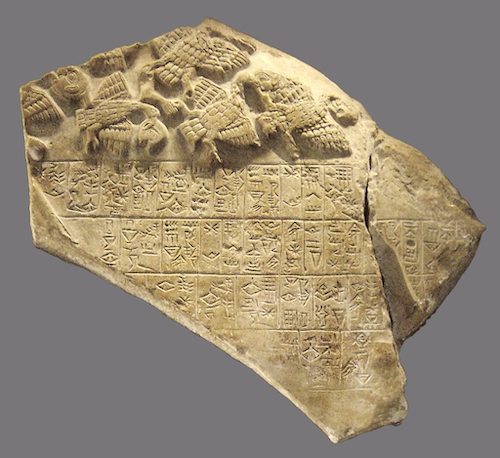

I saw the beautiful Standard of Ur, seen above, when we visited the British Museum last summer. It is about 4,500 years old and was probably constructed in the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics of Lapis Lazuli and shell. The standard of Ur shows the first unambiguous depictions of chariots in war. There has been some debate on whether a Sumerian chariot was actually used in combat. Many scholars believe that it was merely a “battle taxi”, used to convey a commander to a strategic part of the battlefield where he could lead his troops, in the same way that a modern general uses a jeep or helicopter to reach the front lines. Some scholars also believe the chariots were used to carry noblemen to the battle, where they would dismount and then fight on foot. The Standard of Ur along with the Vulture stele are the first depictions of war in history. The Standard of Ur dispels any question that chariots were used directly in combat. They were likely heavy and slow to start but undoubtedly were truly intimidating in combat, with an ability to scatter the enemy lines.

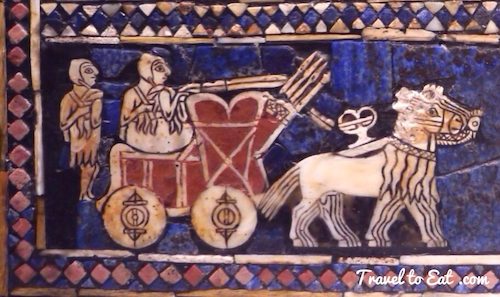

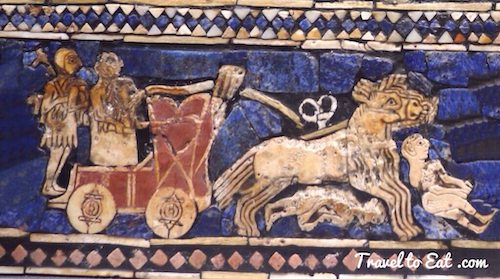

I have extracted the five depictions of Sumerian chariots from the War Panel of the Standard of Ur found by Leonard Woolley in tomb PG779 dating to about 2500 BC for easy comparison. They differ in minor details regarding which weapons are being used at different points in the battle. The Sumerians were pioneers of ancient weaponry, and although they fell to neighboring civilizations, they invented a large number of battle techniques and weapons that were used for years afterwards. The almost constant occurrence of war among the city-states of Sumer for thousands of years spurred the development of military technology and technique far beyond that found elsewhere at the time. The Sumerian chariot was a whole new style of ancient warfare. Never before had the wheel been used in such an offensive way, so the Sumerian invention of the chariot ranks among the major military innovations in history. The Sumerian chariot was usually four-wheeled (although there are examples of the two-wheeled variety in some findings) and they required at least four onagers (wild asses) to pull them. An interesting observation is that the Sumerians controlled the onagers with rings through their noses, while the reins went through rein rings attached to the chariot for greater control.

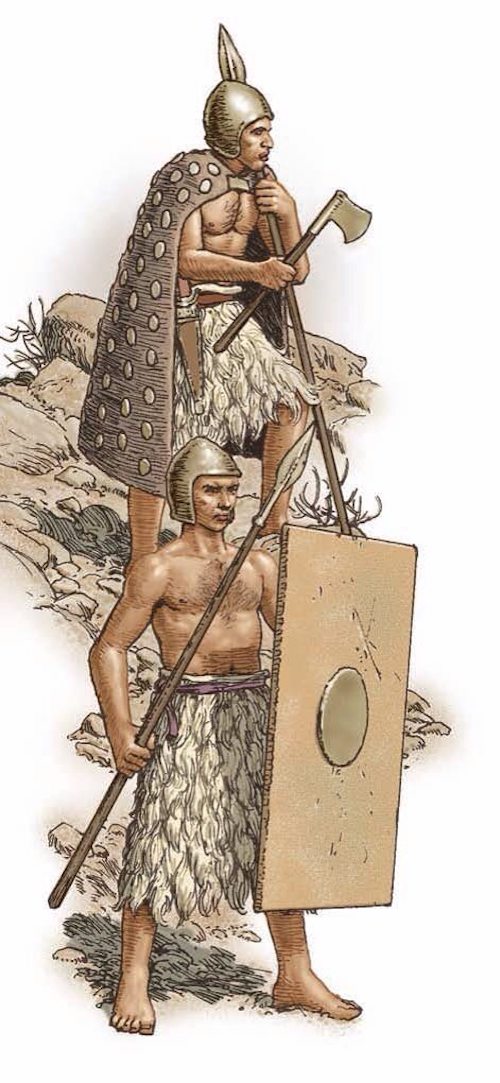

Also note that the driver and soldier wore helmets, leather armor and the horse had armor as well. The stele shows Eannatum's soldiers wearing what appears to be armored cloaks. Each cloak was secured around the neck and was made either of cloth or, more probably, thin leather. Metal disks with raised centers or spines like the boss on a shield were sown on the cloak. Although somewhat primitive in application, the cloak was the first representation of body armor, and would have afforded relatively good protection against the weapons of the day. Later, of course, the Sumerians introduced the use of overlapping plate body armor. The Gold Helmet of King Meskalamdug, c. 2400 BCE, from the royal cemetery at Ur, is made of repoussé gold, height 22 cm, greatest diameter 26 cm. The decoration of the helmet simulates the king's crown, hair, and ears. Holes drilled along the lower edges enabled the attachment of an inner helmet. This is one of many Mesopotamian objects that have recently been lost or stolen from Iraq's museums, and have yet to be recovered. Meskalamdug, Sargon, and Eannatum were all “Kings of Kish”. This is the traditional title held by any king who ruled both Sumer and Akkad.

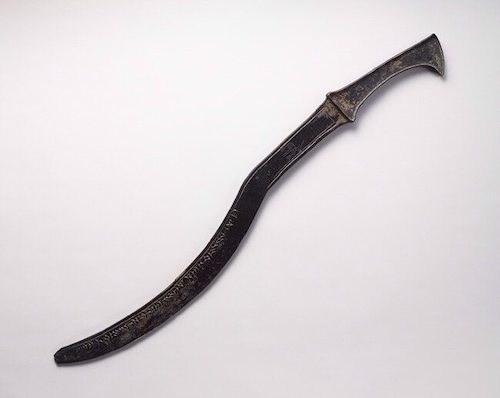

The bronze socket axe remains one of Sumer's major military innovations. When the Sumerians introduced the use of plate body armour, it was quickly followed by the development of the bronze socket axe. By 2500 BC, Sumerian axes had a narrower blade and strong socket, which made them capable of piercing through bronze-plate armours. The bronze socket axe became one of the most devastating weapons of the ancient world, and remained in use for 2,000 years. As an aside, the presence of bronze weapons in Sumer, which has no copper or tin, shows the dramatic influence of wheels and horses to deliver the components for bronze to Sumer.

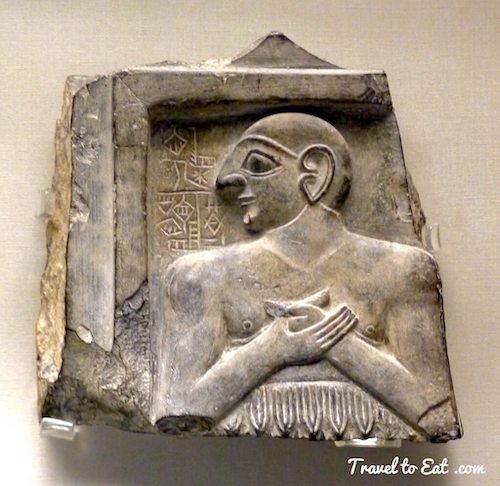

After a resounding victory over the King of Umma in 2525 BC, the King of Lagash, King Enannatum, erected a stele to commemorate the occasion. In commissioning this monument to his victory, the King of Lagash created the first known depiction of war ever created by humanity. The stele's carvings display the troops of Lagash: spearmen arranged in a phalanx formation, with eight men to a row, six rows deep. As a phalanx arrangement would require strict training and discipline, this suggests that the Sumerians had one of the earliest professional armies. Elsewhere on the stele, vultures can be seen carrying away the heads of the fallen Umman warriors. As a result, these Sumerian soldiers have become known as the “Vultures of Sumer.” The website Sumerian Shakespeare believes the Standard of Ur may have been buried with the son of King Enannatum.

The Ljubljana Marshes Wheel is a wooden wheel that was found in the Ljubljana Marshes some 20 km south of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, in 2002. Radiocarbon dating, performed in the VERA laboratory (Vienna Environmental Research Accelerator) in Vienna, showed that it is approximately 5,150 years old, which makes it the oldest wooden wheel yet discovered. It was discovered by a team of Slovene archeologists from the Ljubljana Institute of Archaeology, a part of the Research Center at the Slovene Academy of Arts and Sciences, under the guidance of Anton Velušček.

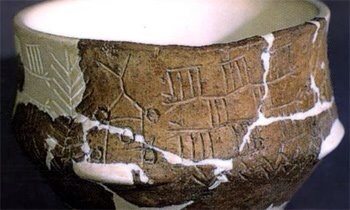

The Bronocice pot is a ceramic vase incised with the earliest known image of what may be a wheeled vehicle. It was dated by the radiocarbon method to 3635-3370 BC and is attributed to the Funnelbeaker archaeological culture. Today it is housed in the Archaeological Museum in Kraków, Poland.

This wheeled ceramic bull was found in the Ukraine. Archaeologists have known about the Trypilian culture since 1896, when Ukrainian archaeologist Vikenty Khvoika discovered an ancient settlement near the village of Trypillia, about 40 km south of modern Kiev, in the Ukraine. It is generally accepted that the Trypilian culture flourished from 5400 to 2700 BC when it was ended by the expansion of the Kurgan culture. The Trypilians bridge the divide between the last phase of the Stone Age and the beginnings of the Copper Age. This period sees the introduction of agriculture into the region, marking a shift in the subsistence strategy for the locals away from nomadic hunting and gathering to a more sedentary way of life.

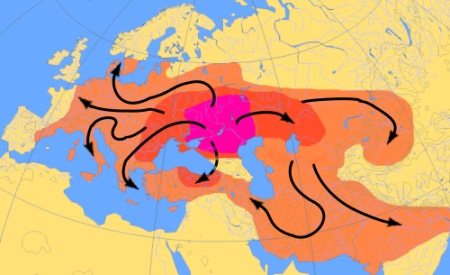

Kurgan is the Turkish term for a tumulus. These are mounds of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. When it was first proposed in 1956, in “The Prehistory of Eastern Europe”, Marija Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was a pioneering interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic-Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Urheimat (homeland), and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken across the region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually expanded until it encompassed the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe, basically modern day Ukraine, Kurgan IV being identified with the Pit Grave (Yamna) culture of around 3000 BC. In fact, the earliest remains in Eastern Europe of a wheeled cart were found in the “Storozhova mohyla” kurgan (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, excavated by Trenozhkin A.I.) associated with the Yamna culture. The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire Pit Grave region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots. The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.

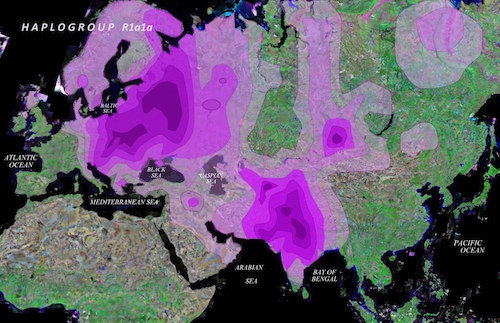

Geneticists have noted the correlation of a specific haplogroup R1a1a defined by the M17 (SNP marker) of the Y chromosome and speakers of Indo-European languages in Europe and Asia. The connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages was first proposed by Zerjal and colleagues in 1999 and subsequently supported by other authors. Spencer Wells deduced from this correlation that R1a1a arose on the Pontic-Caspian steppe (modern day Ukraine). The DNA testing of remains from kurgans also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying an origin close to Europe for this population, the proverbial Aryans, unfortunately made infamous by the Nazis.

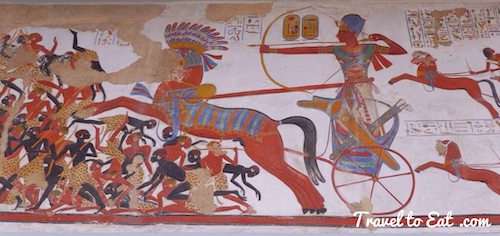

The earliest wheels were solid disk wheels. The invention of the spoke made wheels lighter and transportation swifter, with spoked wheels and chariots appearing around 2200-2000 BC. As we have seen, it is likely that people in the western Eurasian steppes were the first to tame the horse. The horse-drawn chariot was introduced before 2000 BC in the steppes of northeastern Europe, which aided a new phase of the Indo-European expansion. The “mother language” — Proto-Indo-European — was most likely dead as a spoken language by about 2500 BC, but the PIE expansion continued thereafter through its daughter languages. This Egyption chariot is extremely light, with a woven reed floor and only four spokes, while the military model had six spokes. The chariot was built of pieces of wood which had been bent into the required shape by heating them or immersing them in boiling hot water for several hours, bending them and then letting them dry. It would have been fast and very maneuverable but unstable on rough terrain and prone to tipping and breaking. In fact, the use of chariots in Egypt was abandoned in the first millenium BC in favor of horseback riding for precisely these reasons.

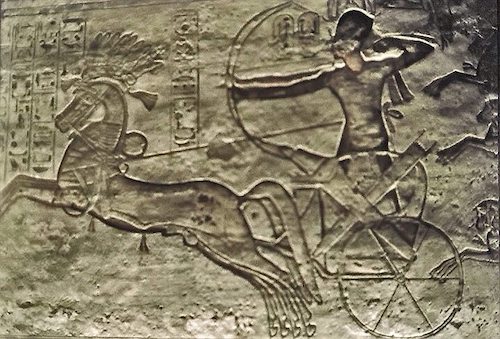

The Battle of Kadesh (also Qadesh) took place between the forces of the Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River, in what is now the Syrian Arab Republic. The battle is generally dated to 1274 BC, and is the earliest battle in recorded history for which details of tactics and formations are known. It was probably the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving perhaps 5,000–6,000 chariots. Ramesses II also campaigned south of the first cataract into Nubia. When Ramesses was about 22, two of his own sons, including Amun-her-khepeshef, accompanied him in at least one of those campaigns. By the time of Ramesses, Nubia had been a colony for two hundred years, but its conquest was recalled in decoration from the temples Ramesses II built at Beit el-Wali.

The Sun Chariot of Trundholm is a late Bronze Age artifact, which is dated to the 14th and the 15th centuries BC. It was discovered in 1902 in the Trundholm moor near Nykøbing Sjælland, Denmark. It is a bronze statue of a horse drawing the Sun in a chariot. The horse drawing the solar disk runs on four wheels, and the Sun itself on two. All wheels have four spokes. The “chariot” consists of the solar disk, the axle, and the wheels, and it is not certain if the sun was imagined as being the chariot itself, or as riding in a chariot.

This post is a little complicated, so a summary is in order. The evidence of wheels exists from the mid-4th millennium BC and domesticated horses exist from at least the 5th millennium, almost parallel in Mesopotamia, Indus Valley, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe, so that which culture originally invented the wheel is not precisely known, although a really good theory is the Kurgan Hypothesis. Roughly half the world's population speaks languages possibly derived from an extinct mother linguistic source known as Proto-Indo-European. All things considered, the first phase of the Indo-European expansion was probably not associated with the slower diffusion of agriculture but with the faster spread of wheeled vehicles after 3500 BC. Whether such vehicles directly triggered the initial IE expansion is not known, but it seems plausible that they aided this by improving mobility, thereby making previously useless steppe grasslands available and converting them into useful animal protein. The domestication of horses and use of the wheel rapidly spread language, the Neolithic package of farming, pottery, and animal husbandry and transformed civilization. Although the whereabouts of where the wheel originated in the beginning is unknown in exact terms, the invention of the wheel is placed during the period in the late Neolithic and can be seen as an important catalyst giving rise to the early Bronze Age. The invention of the wheel is one of the most important inventions of all time. The wheel was later used in different forms such as cart wheel, water wheel, cogwheel, potters wheel and spinning wheel, thus benefiting human civilization in many ways. The invention of the wheel was also at the root of the Industrial Revolution, although it would take a long time to get there. If this subject has piqued your interest, and you want to know more, consider reading the excellent book by David Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language.

References:

Vulture Shield: http://sumerianshakespeare.com/38801.html

First Wheel: https://ktwop.wordpress.com/2012/02/26/earliest-evidence-of-the-wheel-7500-year-old-toy-car-found/

Chariots: http://www.nytimes.com/1994/02/22/science/remaking-the-wheel-evolution-of-the-chariot.html

Wooden Wheel: http://www.sloveniatimes.com/world-s-oldest-wheel-home-after-decade-under-restoration

Spread of the Wheel: http://gatesofvienna.blogspot.com/2011/01/mead-butter-and-indo-europeans.html

Trypilian Culture: http://www.hmns.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=442&Itemid=463

Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trypillian

Kurgan Hypothesis: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_hypothesis

Spencer Wells: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spencer_Wells

The Horse, The Wheel and Language: http://www.amazon.com/The-Horse-Wheel-Language-Bronze-Age/dp/069114818X