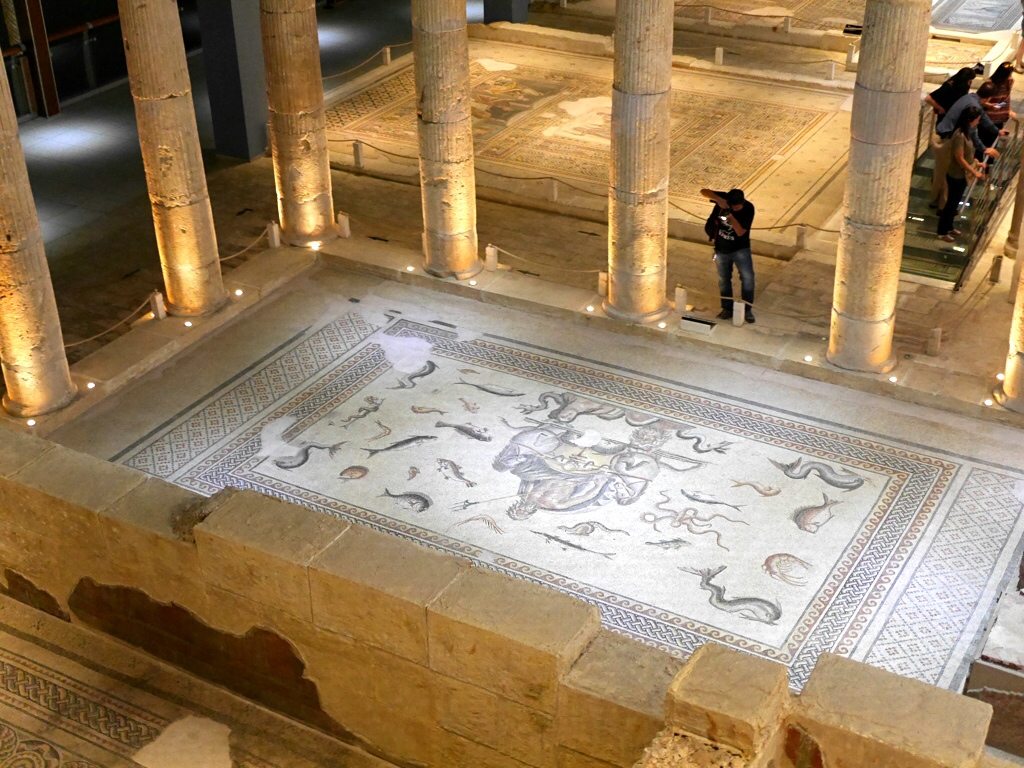

In my previous post, I explored the history of the ancient Roman town of Zeugma. In this and the next post, I will explore the beautiful museum containing the mosaics and objects saved from the floodwaters. The Zeugma Mosaic Museum, in the town of Gaziantep, Turkey, is the biggest mosaic museum on the world, containing 1700 square meters of mosaics . It opened to the public on 9 September 2011. The museum's mosaics are focused on Zeugma, thought to have been founded by a general in Alexander the Great’s army. The treasures, including the mosaics, remained relatively unknown until 2000 when artifacts appeared in museums and when plans for new dams on the Euphrates meant that much of Zeugma would be forever flooded. The 90,000-square-foot museum features a 7,500-square-foot exhibition hall and replaces the Bardo National Museum in Tunis as the world’s largest mosaic museum. The Poseidon and Euphrates Villas, known as the twin villas, have been faithfully recreated with the original mosaics, wall frescoes, fountains, columns and walls placed in their former positions, giving us a profile of a scene from 2000 years ago.

Outside the museum, on the median of the busy street in front of the museum, is a sculpture of a camel caravan, a reminder of the dominant means of transportation of goods in Turkey before the modern era. A statue of Athena, thought to be from the temple in the acropolis of ancient Zeugma, is now in the museum forecourt. Also on display are various columns, funeral steles and even a stone sarcophagus. There is also a nice little café/museum shop for resting before and after your visit.

Dyonysis is the god of fertility and wine, later considered a patron of the arts. He invented wine and spread the art of tending grapes. He has a dual nature. On the one hand bringing joy and divine ecstasy. On the other brutal, unthinking, rage, thus, reflecting both sides of wine's nature. Dionysus is the son of Zeus and Semele. He is the only god to have a mortal parent. The festival for Dionysus is in the spring when the leaves begin to reappear on the vine. It became one of the most important events of the year. Its focus became the theater. Most of the great Greek plays were initially written to be performed at the feast of Dionysus.

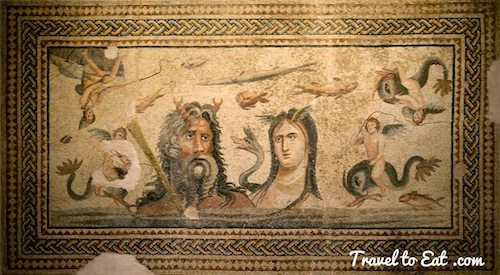

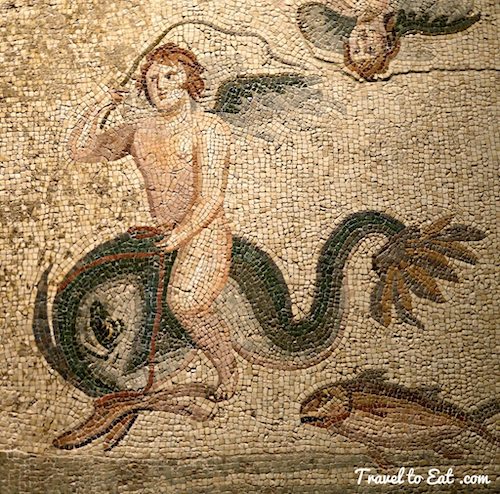

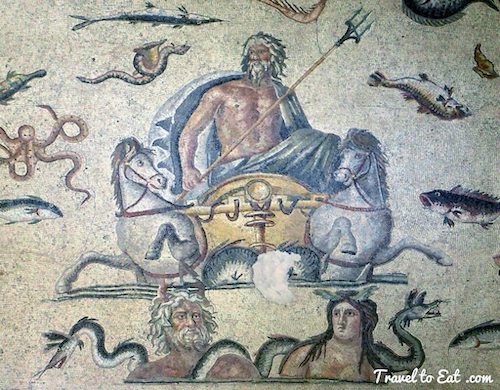

In this mosaic Oceanos is seen with chelas, or claws of a crustacean, which are among his most characteristic attributes. Though the tail of an eel is represented as his feet in the figures on ceramics, in this mosaic he is represented as a bust with Chelsea on his head. His wife Tethys is by his side and represented with wings on her forehead. Between them, there is the dragon called Cetos, which is a mythological sea creature. As seen in the coins of Zeugma, the Euphrates River is expressed as a dragon. Around them are Eros figures riding various species of fish and dolphins. In the top left of the mosaic is a young man thought to be Pan, the patron of fisherman and shepherds.

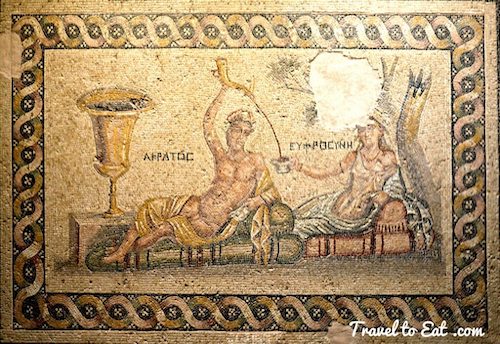

This mosaic was found during the excavations carried out by the Museum of Gaziantep at Zeugma/Belkýs Kelekagzi region. Acratos and Euphrosyne are shown seated and reclining. Acratos is filling Euphrosyne’s cup out of a liquor jug shaped like a deer’s head. On the left there is large container presumably containing wine. In Greek mythology, Euphrosyne was one of the Charites, known in English as the “Three Graces”. Euphrosyne is also the Goddess of Joy or Mirth, a daughter of Zeus and Eurynome, and the incarnation of grace and beauty. The other two Charites are Thalia (Good Cheer) and Aglaea (Beauty or Splendor). Acratos is a God that symbolizes men who are weak against women.

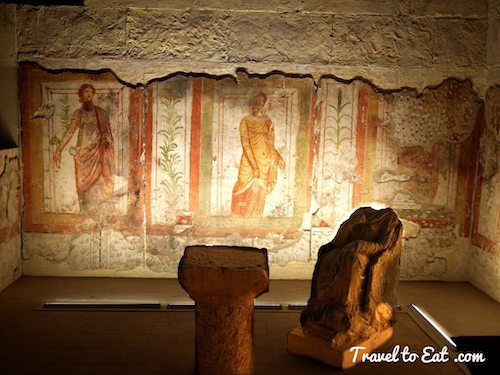

This room with frescos has an additional element of great interest, a game board or counting board. The earliest counting boards are forever lost because of the perishable materials used in their construction. However, educated guesses can be made about their construction based on early writings of Plutarch (a priest at the Oracle at Delphi) and others. In outdoor markets of those times, the simplest counting board involved drawing lines in the sand with fingers or with a stylus, and placing pebbles between those lines as place-holders representing numbers (the spaces between 2 lines would represent the units 10s, 100s, etc.) Affluent citizens could afford small wooden tables having raised borders that were filled with sand (usually colored blue or green). A benefit of these counting boards on tables was that they could be moved without disturbing the calculation— the table could be picked up and carried indoors. In this case, the board is a stone on a pedestal, a rare piece whether it is a game or counting board.

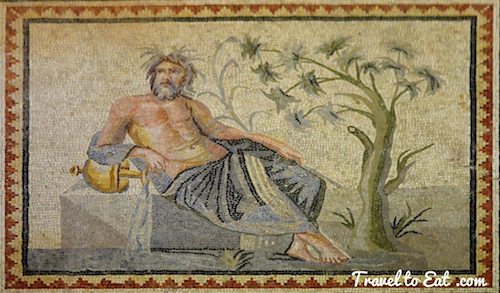

This set of mosaics were designed as a shallow octagonal pool. In the center of the larger pool is the God of the Euphrates. In this mosaic Euphrates can be seen half laying on a couch. The River Euphrates pictured flowing out of a jug under his elbow and the land that has met with the water is covered with green plants. Euphrates holds a branch from a tree. His torso is naked, and there is a tree at his foot. This mosaic was found during the Belkis/Zeugma Necropol digs in 2000 in a Roman villa pool hallway with the Euphrates River Gods. There are two shallow pools in this hallway. According to the myth, Euphrates, for whom the river is named, had a son called Aksurtas. One day this young man was sleeping alongside his mother and Euphrates, who thought that Aksurtas was a stranger, killed his own son. Euphrates later realizes his mistake and jumps in to the River Medos and commits suicide. After that day the river Medos was called Euphrates.

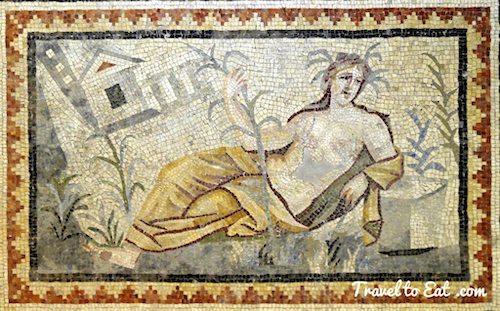

In Greek mythology, the Naiads were a type of water nymph (female spirit) who presided over fountains, wells, springs, streams, brooks, and other bodies of fresh water. They are distinct from river gods, who embodied rivers, and the very ancient spirits that inhabited the still waters of marshes, ponds and lagoon-lakes, such as pre-Mycenaean Lerna in the Argolid. Naiads were associated with fresh water, as the Oceanids were with saltwater and the Nereids specifically with the Mediterranean, but because the Greeks thought of the world's waters as all one system, which percolated in from the sea in deep cavernous spaces within the earth, there was some overlap. Arethusa, the nymph of a spring, could make her way through subterranean flows from the Peloponnesus, to surface on the island of Sicily.

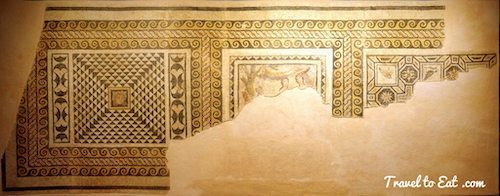

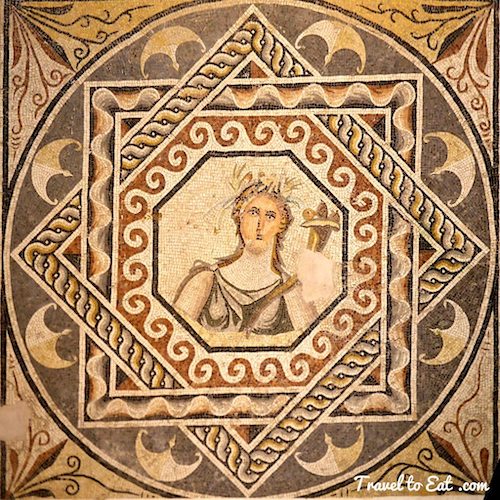

Gaia was the great mother of all: the primal Greek Mother Goddess; creator and giver of birth to the Earth and all the Universe; the heavenly gods, the Titans, and the Giants were born to her. The gods reigning over their classical pantheon were born from her union with Uranus (the sky), while the sea-gods were born from her union with Pontus (the sea). Her equivalent in the Roman pantheon was Terra. This mosaic could also represent the Demeter, the Goddess of Earth and granddaughter of Gaia, with the horn of furtility on her left shoulder in a square shallow pool crowned with flowers and ears of wheat right to the west of Gods related to Euphrates. The mosaic artist has created a situation by first having the water go through the pool where the Gods of the Euphrates are pictured and have it reach the pool where the Goddess of fertility Demeter is and in this way he describes the abundance and fertility Euphrates presents to his surroundings. In addition, Demeter’s bust is placed in the middle of decoration that is seen in the following order, an octagonal band with two equilateral squares rotated 90 degrees and placed inside each other creating eight corners. Eight axe heads are also added. This composition with the geometric decorations of number eight is surrounded by a circular band placed inside a square, decorated with plants. The number eight could have something to do with Demeter’s daughter Persephone. Because Zeus had decided that she should spend 2/3 of the year (8 months) at the time of blossoming and fruit harvest time with her mother Demeter and the other 1/3 winter period with her husband, Hades. In the myth, Demeter doesn’t part with Persephone. Perhaps for this reason in the Zeugma mosaics they are together and Persephone is represented by geometric decorations with the number eight. There are numerous Greek and Roman Goddesses of fertility, harvest, and earth. This could represent either Demeter based on the horn of plenty and the number 8 or Gaia as indicated in the museum.

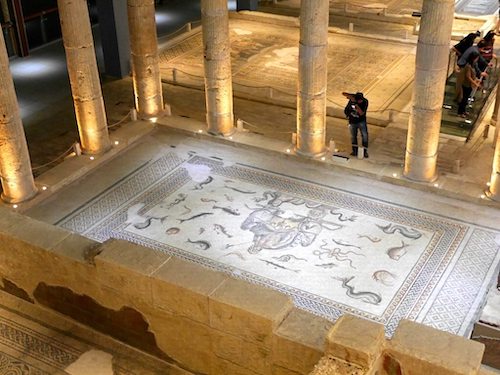

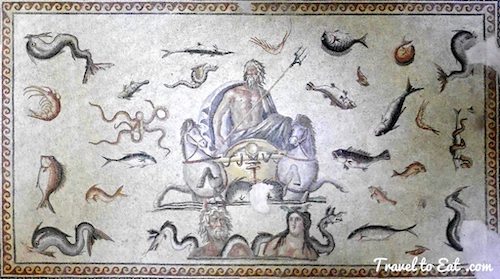

In this mosaic, we recognize Oceanos and his wife Tethys with the Cetos dragon representing the Euphrates on their shoulders. Poiseidon is depicted in a chariot with two horses and his trademark trident. Poseidon is one of the 12 Olympian deities of the pantheon in Greek mythology. His main domain is the ocean, and he is called the “God of the Sea”. Additionally, he is referred to as “Earth-Shaker” due to his role in causing earthquakes, and has been called the “tamer of horses.” He is usually depicted as an older male with curly hair and beard. The name of the sea-god Nethuns in Etruscan was adopted in Latin for Neptune in Roman mythology; both were sea gods analogous to Poseidon. Homer and Hesiod suggest that Poseidon became lord of the sea following the defeat of his father Kronos, when the world was divided by lot among his three sons; Zeus was given the sky, Hades the underworld, and Poseidon the sea, with the Earth and Mount Olympus belonging to all three. Homer claims Oceanus and Tethys, pictured in the lower half of this mosaic, were responsible for the birth of the gods, but Hesiod's version of the origins is generally accepted. Gods of the sea, Oceanus and his wife Tethys bore 3,000 daughters and 3,000 sons. Known as the Oceanids, these children were spirits of rivers, waters, and springs. Poseidon, chief of the water deities and second in power only to Zeus, carried a trident, with which he could shake the earth, call forth or dissipate storms, and the like. To impress Demeter, who urged him to create the world's most beautiful animal, Poseidon invented the horse. Horses with brass hoofs and golden manes drew his chariot across the seas, which became calm before him.

In this post we have spent more than a little time exploring the various Water Gods and it makes sense to explore the world view of the Romans as it relates to oceans. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the ocean was considered to be a river running around the world, a view that began in Sumeria and was reinforced by the T-O maps of Anaximander in 546 BC and Hecataeus in 476 BC. In the deforested relative desert of southeastern Turkey, the inhabitants of the Roman city of Zeugma were particularly cognizant of the the relation between water, rain and water table as they related to fertility of the soil, the heavens and the earth. The linkage of the heavens, earth, and underworld was accomplished through remarkable insight by the Romans through the various Water Gods.

[mappress mapid=”29″]

References:

Go Turkey: http://www.goturkey.com/en/pages/content/839/gaziantep-zeugma-mosaics-museum

Muze: http://m.muze.gov.tr/MuseumDetail.aspx?museumID=28

Babylonian World Map: /babylonian-world-map-british-museum-london/

Counting Board: /musee-des-arts-et-metiers-paris/