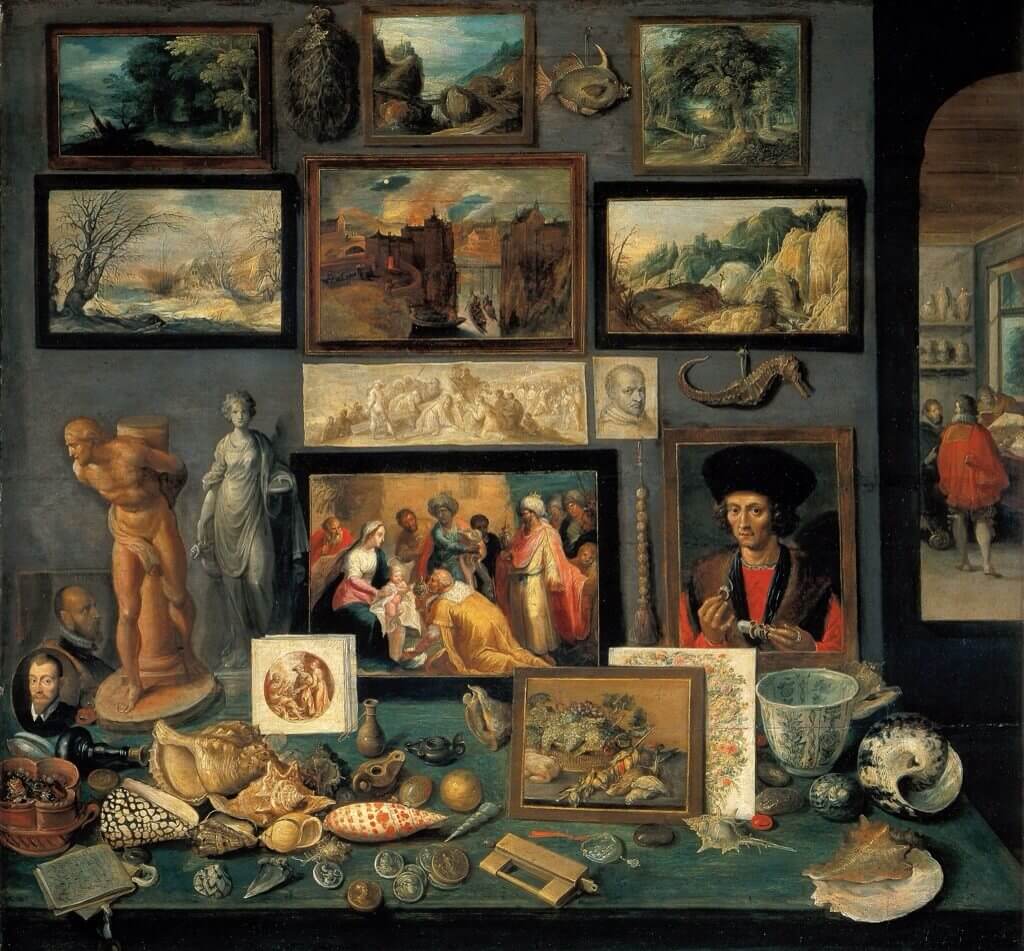

A cabinet of curiosities was an encyclopedic collection in Renaissance Europe of types of objects whose categorial boundaries were yet to be defined. They were also known by various names such as Cabinet of Wonder, and in German Kunstkammer (“art-room”) or Wunderkammer (“wonder-room”). Modern terminology would categorize the objects included as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings) and antiquities. “The Kunstkammer was regarded as a microcosm or theater of the world, and a memory theater. The Kunstkammer conveyed symbolically the patron's control of the world through its indoor, microscopic reproduction.” Besides the most famous and best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe also formed collections that were precursors to museums.

The five ingredients for success in showcasing a collector's panoramic education and broad humanist learning were naturalia (products of nature), arteficialia (or artefacta, the products of man), scientifica (the testaments of man's ability to dominate nature, such as astrolabes, clocks, automatons, and scientific instruments), exotica (collected from distant lands) and antiquities. On the Italian peninsula, the space housing these objects was called a stanzino, studiolo, more often museo, or sometimes galleria, a name mostly applied to collections of paintings and works of art that could contain curiosities as well, such as the Medici galleria. North of the alpine mountains, these predecessors of modern museums were called Kunst-und Wunderkammer (cabinet of art and marvels) or Kuriositäten and Raritäten-Kabinett or Kammer (cabinet or room of curiosities or rarities). The term Kunst-und Wunderkammer was apparently first employed by Count Froben Christoph of Zimmern and Johannes Müller in their historical account Zimmerische Chronik of 1564–66.

The art and curiosities cabinets (or rooms) emerged in Europe in the 16th Century, when the royal courts were taken with the collecting passion. They collected not only art, but everything that appeared in time and therefore was of interest: paintings, engravings and sculptures were of course to be included as well as books of all knowledge areas, coins and medals, astronomical instruments, globes, atlases, skeletons, fossils and minerals, sophisticated fine works of ivory, elaborately engraved ostrich eggs, precious gilded coconuts and much more. The Hall of Antiquities (Antiquarium), built between 1568-1571 for the collection of Duke Albert V (1550–1579) by Wilhelm Egkl and Jacobo Strada, is the largest Renaissance hall north of the Alps and one of the first museums, The Munich Art Chamber. Albert was a patron of the arts and a collector whose personal accumulations are the basis of the Wittelsbach antique collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, the coin collection and the Wittelsbach treasury in the Munich Residenz; some of his Egyptian antiquities remain in the collection of Egyptian art. His personal library has come to the Bavarian State Library in Munich, inheritor of the Wittelsbach court library.

One of the first scholars who dealt with the theoretical basics of collecting, was the Belgian Samuel Quiccheberg (Antwerp 1529 – 1567 Munich). He published his “Treatise Inscriptiones vel Tituli Theatri Amplissimi” in 1565 to establish the beginning of the teaching museum in Germany. This first theory with practical guidance on the design and presentation of the objects in a museum, influenced the Munich Art Chamber, which was built at the same time. Quiccheberg's extraordinary achievement is to combine the traditional fields of art and curiosities with the Naturalia, Mirabilia, Artefacta, Scientifica, Anitquites and Exotica to a unit that justifies the term museum. He designed a five-part classification system for his ideal museum (“Theatrum”). The text gives a deep insight into the world of collecting in the 16th Century.

Of course, one of the most famous Renaissance museums in the world is the Uffizi in Florence, begun by Giorgio Vasari in 1560 for Cosimo I de' Medici as the offices for the Florentine magistrates, hence the name “uffizi” (“offices”). Construction was continued to Vasari's design by Alfonso Parigi and Bernardo Buontalenti and ended in 1581. Over the years, further parts of the palace evolved into a display place for many of the paintings and sculpture collected by the Medici family or commissioned by them. According to Vasari, who was not only the architect of the Uffizi but also the author of Lives of the Artists, published in 1550 and 1568, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo gathered at the Uffizi “for beauty, for work and for recreation.” The collections would become more vast, continually enriched by almost every member of the Medici dynasty until their extinction in the XVIIIth century. The Gallery was opened to the public later, in 1769, by Grand Duke Peter Leopold, maybe the most enlightened and important member of the Austrian house of Lorraine, new regent family of the Grand Duchy until the unification of Italy. Johann Zoffany, born in Germany but active in England after the 1760's, was commissioned by England's Queen Charlotte to create this pictorial account of the Uffizi. Zoffany set his painting in the octagonal room called the Tribuna. Zoffany sets into this room a group of English gentlemen who are admiring the masterpieces.

Another famous painting by Johann Zoffany is this imaginary depiction of the apartment of Charles Townley of the Townley Marbles donated to the British Museum. The marbles were overshadowed at the time, and still today, by the Elgin Marbles. Prominent in front are Townley's Roman marble of the Discobolos, the Nymph with a Shell, of which the most famous variant was also in the Borghese collection and a Faun of the Barberini type. On the bookcase, the Townley Vase and right, on a puteal, the Townley Venus.

This studiolo, or study, is one of the most important works of art of the Italian Renaissance in America. It was commissioned around 1476 by Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482), Duke of Urbino, for his residence in the small city of Gubbio, north of Perugia in the foothills of the Appenine mountains in Italy. A duplicate was executed in Urbino, a room measuring just 3.60 x 3.35m and facing away from the city of Urbino and towards the Duke's rural lands. The studiolo was intended to provide a place for intellectual pursuits, examining confidential papers or private possessions, or receiving special visitors. The walls of the small room are carried out in wood inlay. Thousands of tiny pieces of different kinds of wood have been used to create the illusion of walls lined with cupboards. Their lattice doors are open, revealing a dazzling array of the accoutrements of the duke's life. Armor and insignia refer to his prowess as a warrior and wise governor; musical and scientific instruments and books attest to his love of learning. Also he could arrange to have anything he wanted on the shelves.

The technique that is employed here is intarsia, the Italian word for wood inlay. This technique was used to create intricate pictorial images like these set into paneling, doors, or furniture. Everything in the studiolo looks three-dimensional, as if intended to fool us into thinking these objects are real. This device is called trompe l'oeil (French for “fool the eye”). The designer of the studiolo enhanced this illusion of three-dimensionality by using a system of linear perspective that had only recently been formulated by the great Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi. The irony of this studiolo is that Montefeltro lost his right eye when young and had no depth perception, it probably looked even more real to him.

Perhaps the grandest studiolo was the “Camerino” (“little room”) of Alfonso d'Este in Ferrara, for which the greatest painters of the day were commissioned from about 1512-1525 to paint mythological canvases, very large by the standards of the time. Fra Bartolommeo died before starting work, and Raphael got no further than a drawing, but Giovanni Bellini completed The Feast of the Gods (NGA, Washington) in 1514. Titian was then brought in and added three of his finest works: Bacchus and Ariadne (National Gallery, London), The Andrians and The Worship of Venus (both Prado, Madrid), as well as repainting the background of the Bellini to match his own works better.

Another famous treatise on Museums was Caspar Friedrich Neickel’s Museographia. With this book, Neickel became a founder of modern day collection management. It has one copper-plate etching – an illustration of the collection room and its arrangement. For English speakers, this is the key to Museographia’s contents. Classifying the world was fundamental to collection management in Neickel’s time and remains so today. Neickel or Einckel, Jenckel or Jencquel was passionate about collections and kept one himself. He researched 128 other publications to write Museographia, had it edited by Dr Johann Kanold and published it in 1727 under the pseudonym “C F Neikelius”. Museographia appeared when man was classifying the world. Only a few years later, Carl Linneaus established ‘genus’ and ‘species’ in his work, which influenced Darwin’s theories of evolution. Man classified the world and the museum was his prototype.

The Salzburg Cathedral Museum (Dommuseum) is dedicated to the art and the culture of one of the oldest Archbishoprics in German-speaking territories. It displays art treasures from the cathedral and the churches of the archdiocese. Artifacts spanning the Cathedral's 1300-year history, including medieval sculptures, baroque paintings and goldsmith's art from the Cathedral treasure. The exhibits range from the 8th century Carolingian St. Rupert’s crucifix, 12th to 18th century objects from the Cathedral treasury, for example Prince Archbishop Wolf Dietrich’s monstrance of 1697, sculpture and paintings from the 15th to the 18th century, to the 17th century curiosities of the “Royal Art and Rarities Collection” collected by the archbishops, which has mostly been dispersed. The extensive artifacts dating from Salzburg's Baroque Era include works by Georg Raphael Donner, Johann Michael Rottmayr and Paul Troger.

The Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck was created by Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria (1529-1595) in the 16th century. Representing an excellent example of a late Renaissance encyclopedic collection of its genre, unlike many other collections, it continues to be displayed at Ambras Castle, the same setting since its inception. Ferdinand II, like many other rulers of the Renaissance, was interested in promoting the arts and sciences. He spent considerable time and money on his unique collection and converted the medieval Ambras Castle into a contemporary palace to display his possessions. Beside the chamber of arts and curiosities the castle is home to a collection of medieval and early modern weapons and the “Habsburg Portrait Gallery”. Today these collections are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and at Castle Ambras.

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576-1612), housed in the Hradschin in Prague was unrivalled north of the Alps; it provided a solace and retreat for contemplation that also served to demonstrate his imperial magnificence and power in symbolic arrangement of their display, ceremoniously presented to visiting diplomats and magnates. Rudolf moved the Hapsburg capital from Vienna to Prague in 1583. Rudolf loved collecting paintings, and was often reported to sit and stare in rapture at a new work for hours on end. He spared no expense in acquiring great past masterworks, such as those of Dürer and Brueghel. Rudolf's successors did not appreciate the collection and the Kunstkammer gradually fell into disarray. Some 50 years after its establishment, most of the collection was packed into wooden crates and moved to Vienna. The collection remaining at Prague was looted during the last year of the Thirty Years War, by Swedish troops who sacked Prague Castle in 1648, also taking the best of the paintings, many of which later passed to the Orléans Collection after the death of Christina of Sweden. The painting “Rudolf II as Vertumnus” was taken as war booty by Sweden in Prague in 1648.

As my last example, I present the repository of the House of Hapsburg, the Kunstkammer Wien in Vienna, the biggest and best of all the Kunstkammers, closed since 2002 and just reopened this year, 2013. The following collections provided the basis for the Kunstkammer Wien:

- The Kunst- and Wunderkammer of Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria (1529-1595).

- The older collections of the emperors Friedrich III, Maximilian I and Ferdinand I.

- Archduchess Margaret of Austria (1480-1530) Kunstkammer from the Netherlands

- The Kunstkammer of Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612), which he assembled in Prague.

- The Kunstkammer of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614-1662) from the Netherlands.

- The Vienna Treasury (Schatzkammer), originally the oldest of the Habsburg Kunstkammer.

It was not until 1875, under the reign of Emperor Francis Joseph I, that a large reform of the imperial collections was undertaken. All of the various holdings were brought together at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which opened in 1891, leaving only those objects in the Treasury that had the character of insignia or that were souvenirs of members of the imperial family. The Kunsthistorisches Museum and the the Natural History Museum are the most important large buildings of the Ringstrasse. The two museums have identical exteriors and face each other across Maria-Theresien-Platz. The Ringstraße (or Ringstrasse) is a circular road surrounding the Inner Stadt district of Vienna, Austria and is one of its main sights. The Kunsthistorisches Museum is considered as one of the first art museums in the old world and one of the largest, comparable to the Louvre. After the collapse of the monarchy in 1918, 800 tapestries came into the collection, which had originally served the design of the imperial palaces. Since 1963, all parts of the collection are reunited in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. There are nine divisions:

- The Egyptian and Near East Collection

- The Greek and Roman Collection

- The Coins and Medals Collection

- Arms and Armor Collection

- Kunstkammer Wien

- Pictures Collection

- Musical Instruments Collection

- Ephesos Collection

- Library

In this post I have focused on German and Italian collectors because that was where the early Renaissance collectors were. The Renaissance was the Age of Exploration, a period of rapidly expanding horizons of knowledge and the constant attempt to achieve the seemingly unachievable. All over Europe the Renaissance had stimulated people high and low to re-evaluate their surroundings. I will leave you with a short list of other collectors:

- King Charles V of France (1337-1380) and his younger brother Duke of Berry (1340-1416) were collectors. In particular the Duke of Berry had collections in the Palace of Bourges which were the among the first model of a universal art chamber.

- Claude du Molinet (1620 – 1687) in the abbey of Sainte Geneviève in Paris.

- Louis XIV Versailles 1682 and the French Revolution, Louvre 1793

- The lavish Cabinet of Curiosities of Bonnier de la Mosson (1702-1744), the Museum of Natural History in the Jardin des Plantes.

- In 1759, George II's royal library was added to Sloane’s collection to form the foundation of the British Museum.

- Cornelis van der Geest (1577-1638) was a spice merchant from Antwerp, who used his wealth to establish his art collection.

- Two of the most famously described 17th century cabinets were those of Ole Worm, known as Olaus Wormius (1588–1654) and Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680).

- Frederick III of Denmark (1609-1670), who added Worm's collection to his own after Worm's death.

- The Kunstkamera founded by Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg in 1727.

- Pope Julius II founded the Vatican museums in the early 16th century with the discovery of “Laocoön and his Sons” in 1506

References:

Kunstkammer: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kuns/hd_kuns.htm

Kunstkammer Wein: http://www.khm.at/en/visit/collections/kunstkammer-wien/

Kunstkammer George Lau: http://www.kunstkammer.com/e_seiten/framestart.html

Wunderkammern Italian Group: http://www.wunderkammern.net//

Cabinet Magazine: http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/

Zymoglyphic: http://www.zymoglyphic.org/exhibits/baroquemuseums.html

Dommuseum Strausbourg: http://www.kirchen.net/dommuseum/page.asp?id=2426

Uffizi: http://www.uffizi.org/

Studiolo of Francesco: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Studiolo_of_Francesco_I

Cabinets of Curiosity: http://www.musaeum.org/cabinets/cabinets.html

Margaret of Austria: /conrad-meit-sculptor-cathedrale-saints-michel-et-gudule-brussels/