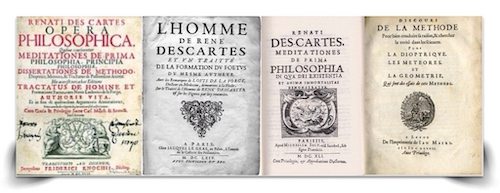

Descartes is the father of modern philosophy, abstract, mathematical and scientific. In mathematics he is the father of algebraic geometry and laid the groundwork for the calculus of Newton and Leibnitz. In general Descartes rejected empirical knowledge for experimental confirmation, the throwing out several millennia of Aristotelian “science”. He even rejected the existence of his own body and the sensations provided by it. All knowledge must be proven and it set the stage for the enlightenment and rationalism. He developed an early form of the law of conservation of mechanical momentum. “Thus, God imparted various motions to the parts of matter when he first created them, and he now conserves all this matter in the same way, and by the same process by which he originally created it; and it follows from what we have said that this fact alone makes it most reasonable to think that God likewise always conserves the same quantity of motion in matter.” I hear echos of the conservation of mass espoused by Levoisier, the father of modern chemistry, Leibniz conservation of energy, Joule's mechanical equilalence of heat and even Einstein's conservation of matter and energy.

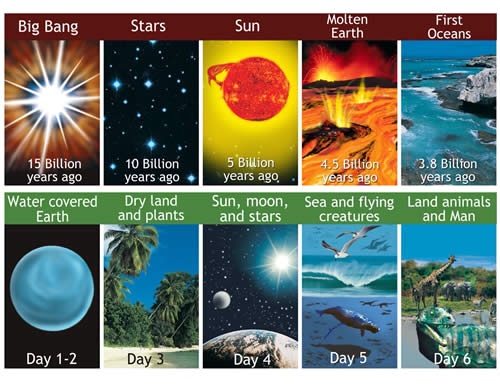

He also wrote: “I was not, however, disposed, from these circumstances, to conclude that this world had been created in the manner I described; for it is much more likely that God made it at the first such as it was to be. But this is certain, and an opinion commonly received among theologians, that the action by which he now sustains it is the same with that by which he originally created it; so that even although he had from the beginning given it no other form than that of chaos, provided only he had established certain laws of nature, and had lent it his concurrence to enable it to act as it is wont to do, it may be believed, without discredit to the miracle of creation, that, in this way alone, things purely material might, in course of time, have become such as we observe them at present; and their nature is much more easily conceived when they are beheld coming in this manner gradually into existence, than when they are only considered as produced at once in a finished and perfect state.” A heretical statement among others that caused, in 1663, the Pope to place his works on the Index of Prohibited Books.

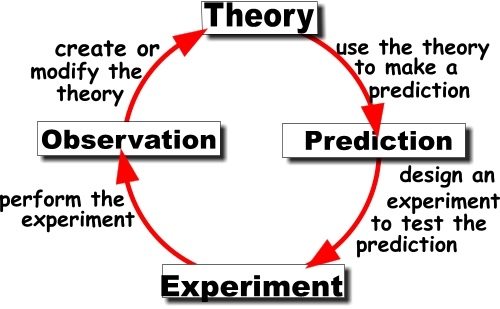

As clear a statement of the scientific method that I have ever read is contained in his conclusion: “I remarked, moreover, with respect to experiments, that they become always more necessary the more one is advanced in knowledge; for, at the commencement, it is better to make use only of what is spontaneously presented to our senses, and of which we cannot remain ignorant, provided we bestow on it any reflection, however slight, than to concern ourselves about more uncommon and recondite phenomena: the reason of which is, that the more uncommon often only mislead us so long as the causes of the more ordinary are still unknown; and the circumstances upon which they depend are almost always so special and minute as to be highly difficult to detect. But in this I have adopted the following order: first, I have essayed to find in general the principles, or first causes of all that is or can be in the world, without taking into consideration for this end anything but God himself who has created it, and without educing them from any other source than from certain germs of truths naturally existing in our minds In the second place, I examined what were the first and most ordinary effects that could be deduced from these causes; and it appears to me that, in this way, I have found heavens, stars, an earth, and even on the earth water, air, fire, minerals, and some other things of this kind, which of all others are the most common and simple, and hence the easiest to know. Afterwards when I wished to descend to the more particular, so many diverse objects presented themselves to me, that I believed it to be impossible for the human mind to distinguish the forms or species of bodies that are upon the earth, from an infinity of others which might have been, if it had pleased God to place them there, or consequently to apply them to our use, unless we rise to causes through their effects, and avail ourselves of many particular experiments. Thereupon, turning over in my mind I the objects that had ever been presented to my senses I freely venture to state that I have never observed any which I could not satisfactorily explain by the principles had discovered.” This statement was the commencement of real deductive reasoning in the world and led to 3 1/2 centuries of technological development and the industrial revolution.

So, given this splendid treatise and his manifesto, cogito ergo sum, “I think, therefore I am” what is left to say? Well, simply the same questions that have plagued mankind since time immemorial, the place of God, church and state in the world. Moreover such radical proposals had equally radical implications for society. The Age of Enlightenment (or simply the Enlightenment or Age of Reason) was a cultural movement of intellectuals in the 17th and 18th centuries, which began first in Europe and later in the American colonies. Its purpose was to reform society using reason, challenge ideas grounded in tradition and faith, and advance knowledge through the scientific method. It promoted scientific thought, skepticism and intellectual interchange and opposed superstition, intolerance and some abuses of power by the church and the state. The ideas of the Enlightenment have had a major impact on the culture, politics, and governments of the Western world. The Scientific Revolution is closely tied to the Enlightenment, as its discoveries overturned many traditional concepts and introduced new perspectives on nature and man's place within it. The Enlightenment flourished until about 1790–1800, after which the emphasis on reason gave way to Romanticism's emphasis on emotion, and a Counter-Enlightenment gained force.

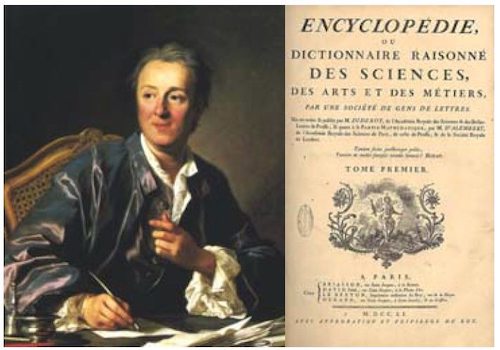

In France, Enlightenment was based in the salons and culminated in the great Encyclopédie (1751–72) edited by Denis Diderot and (until 1759) Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1713–1784) with contributions by hundreds of leading philosophes (intellectuals) such as Voltaire (1694–1778), Rousseau (1712–1778) and Montesquieu (1689–1755). Chartier (1991) skeptically argues that the Enlightenment was only invented after the fact for a political goal. He claims the leaders of the French Revolution created an Enlightenment canon of basic text, by selecting certain authors and identifying them with The Enlightenment in order to legitimize their republican political agenda.

This period saw the shaping of two distinct lines of enlightenment thought: Firstly the radical enlightenment, largely inspired by the one-substance philosophy of Spinoza, which in its political form adhered to: “democracy; racial and sexual equality; individual liberty of lifestyle; full freedom of thought, expression, and the press; eradication of religious authority from the legislative process and education; and full separation of church and state”. Secondly the moderate enlightenment, which in a number of different philosophical systems, like those in the writings of Descartes, John Locke, Isaac Newton or Christian Wolff, expressed some support for critical review and renewal of the old modes of thought, but in other parts sought reform and accommodation with the old systems of power and faith.

Cartesian doubt is a systematic process of being skeptical about (or doubting) the truth of one's beliefs, which has become a characteristic method in philosophy. This method of doubt was largely popularized in Western philosophy by René Descartes, who sought to doubt the truth of all his beliefs in order to determine which beliefs he could be certain were true. Descartes' method is broken into four “scientific” steps including

- accepting only information you know to be true

- breaking down these truths into smaller units

- solving the simple problems first

- making complete lists of further problems

This is also known as hyperbolic doubt or having the tendency to doubt, since it is an extreme or exaggerated form of doubt. Knowledge in the Cartesian sense means to know something beyond not merely all reasonable, but all possible, doubt. In his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), Descartes resolved to systematically doubt that any of his beliefs were true, in order to build, from the ground up, a belief system consisting of only certainly true beliefs. Consider Descartes' opening lines of the Meditations:

Several years have now elapsed since I first became aware that I had accepted, even from my youth, many false opinions for true, and that consequently what I afterward based on such principles was highly doubtful; and from that time I was convinced of the necessity of undertaking once in my life to rid myself of all the opinions I had adopted, and of commencing anew the work of building from the foundation…

Fundamental to scholastic philosophy, thus in the historical context of Descartes, is the question of how causation is divided or shared between God and creatures. The moderate and consensus position among scholastics is that, while God is the universal and primary cause of being and change in the universe, the natures of created things provide a realm of secondary causes. Natural substances (and persons) are ultimately instruments of divine providence (Aquinas) and are able to possess their own causal efficacy only as subject to the divine concursus, but they are genuine efficient causes of change in another. In shifting the debate from “what is true” to “of what can I be certain”, Descartes shifted the authoritative guarantor of truth from God to humanity. While the traditional concept of “truth” implies an external authority, “certainty” instead relies on the judgment of the individual. In short, individuals are imbued with true free will within the constraints of the laws of nature, or divine concursus, provided by God. God does not continually monitor the actions of a ball in flight or a person at work but instead provides for and maintains the reality in which both exist.

All of this reminds me of the paradox of modern life. The obvious power of the scientific method is manifest in everything, light bulbs, computers and telescopes at the very least. Yet the question of God and/or politics defies all reason. Einstein wrote, “I believe in Spinoza's God, who reveals himself in the harmony of all that exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.” He also famously wrote: “Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind”. He expanded these thoughts:

“Scientific research can reduce superstition by encouraging people to think and view things in terms of cause and effect. Certain it is that a conviction, akin to religious feeling, of the rationality and intelligibility of the world lies behind all scientific work of a higher order… This firm belief, a belief bound up with a deep feeling, in a superior mind that reveals itself in the world of experience, represents my conception of God. In common parlance this may be described as “pantheistic” (Spinoza).”

“A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, of the manifestations of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which are only accessible to our reason in their most elementary forms, it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute the truly religious attitude; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man.”

I am, by training, a mathematician and a physicist. In addition I have been a practicing physician for over 20 years. I would seem to be qualified to have an opinion in these matters, yet I have nothing to add to the comments of Einstein, though I share his belief in a pantheistic God. The problem with science and with Descartes philosophy comes down to the first hypothesis or belief on which all further knowlege is based. Believe in God and all is revealed, without a first hypothesis the entire structure of science, or if you put it in Descartes's terms, the concursus or spiral of civilization and reason comes crashing down. The world is rational, follows rules precisely, whether that is by God's design or because our own thoughts impose those rules on a very different reality. Perhaps it is my age, but it is too easy to involve yourself in the predictable happenings in the middle of life, too difficult and yet so important to contemplate origins and endings. That is in part the rationale for this blog, a perusal of knowledge, places and things I had no time to pursue in the first part of my life and a search for beginnings, in a sense a search for the elusive first hypothesis to build upon. In any case, you can recognize in Descartes a truly modern worldview, perhaps the first in history, who would be perfectly at home in today's world, the world he helped to create.

References:

Descartes Discourse on Method: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/59

Descartes Passions of the Soul: http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/despas.html

Rules for the Direction of the Mind: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Rules_for_the_Direction_of_the_Mind

Descartes Meditations: http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/pdf/descmedi.pdf

Descartes on God, Creation, and Conservation by Richard F. Hassing: http://philosophy.tamu.edu/~sdaniel/682%20Readings/hassing%20creation.pdf

Causation and Modern Philosophy edited by Keith Allen, Tom Stoneham

The Big Bang: http://www.answersingenesis.org/articles/nab2/does-big-bang-fit-with-bible

Einstein and Religion: http://www.einsteinandreligion.com/

Einstein The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2008/may/12/peopleinscience.religion

World Union of Deists: http://www.deism.com/einstein.htm

Frans Hals: /frans-hals-louvre/