‘Gypsy Girl’ (also known as ‘Bohemian’) is an oil painting on wood created by Frans Hals in approximately 1628-1630. It depicts a young gypsy wench who appears to be slightly leaning her right arm on a table or counter, and bears a sly and somewhat mischievous smile on her face. Each brush stroke has been exquisitely executed as to create a particular elegance to her burly physique. She seems to be facing a window that illuminates her face, drawing the viewer’s attention to her voluptuous breasts. She dons a red overdress, with a low-cut white shirt underneath. Hals well-known portraiture talents are most apparent in ‘Gypsy Girl’ as he masterfully contrasts her hardened street-smart appearance with the soft, natural beauty of her inner self. She seems happy with her life.

Hals was a master of a technique that utilized something previously seen as a flaw in painting, the visible brushstroke. The soft curling lines of Hals’ brush are always clear upon the surface: “materially just lying there, flat, while conjuring substance and space in the eye.” Hals was fond of daylight and silvery sheen, while Rembrandt used golden glow effects based upon artificial contrasts of low light in immeasurable gloom. Both men were painters of touch, but of touch on different keys — Rembrandt was the bass, Hals the treble.

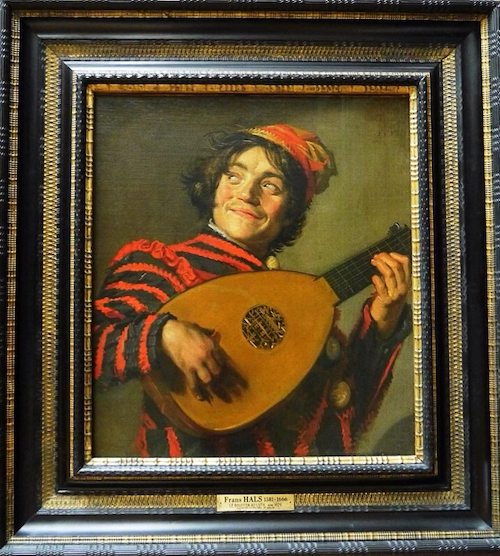

In the painting seen above from the Louvre, “Buffoon Playing a Lute” from 1623-1624, you can see the same mischievous energy seen in Gypsy Girl. A wide, perhaps ironic smile lights up the whole of the lutist’s face, giving it enormous life. The natural spontaneity that the picture exudes is undoubtedly due to the fact that the artist studied a real man, the same model who is found in several other of his pictures. However, this is not strictly speaking a portrait, although Hals became famous for these too. Portrait commissions were restricted to the upper classes of society-the nobility, the middle classes, or perhaps men of letters who had themselves painted in conventional, rather static poses.

By the 1620s Hals had definitively evolved a technique that was close to impressionism in its looseness. Like the contemporary Spanish painter Diego Velázquez, he used colour to structure forms; and this use of colour is what sets the two artists apart from their contemporaries. Unique to Hals, however, is his use of quick, loose strokes of bright colour that suggest rather than enclose form and are highly expressive of movement and of the subjects’ vitality. Most painters of the 17th century approached their paintings slowly, with preparatory drawings, a certain amount of underpainting, and an elaborate finish. Although there is no certain evidence of his method, Hals seems to have started directly on the canvas and painted quickly, leaving his first spontaneous expression, which is almost an oil sketch, as the finished work. Hals continued to use this technique, which gave a striking immediacy to his perceptive portrayals of character, all his life, painting with increasing freedom as he grew older. In his group portraits, such as The Banquet of the Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company in 1627, Hals captures each character in a different manner. The faces are not idealized and are clearly distinguishable, with their personalities revealed in a variety of poses and facial expressions.

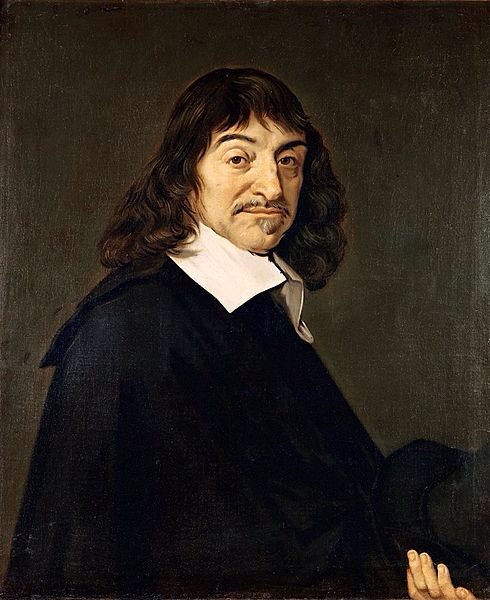

As early as the 17th century, people were struck by the vitality of Frans Hals’ portraits. For example, Haarlem resident Theodorus Schrevelius noted that Hals’ works reflected “such power and life” that the painter “seems to challenge nature with his brush”. His most noted portrait today is the one he made in 1649 of René Descartes. The copy displayed in the Louvre is certainly a different style, it really is too bad that the condition of the original is so deteriorated. Centuries later Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: “What a joy it is to see a Frans Hals, how different it is from the paintings, so many of them, where everything is carefully smoothed out in the same manner”. Hals chose not to give a smooth finish to his painting, as most of his contemporaries did, but mimicked the vitality of his subject by using smears, lines, spots, large patches of color and hardly any details. Frans Hals did not prefer a particular type of model; he painted all classes from the lower to the upper. Due to his unique artistic style, he left no followers, but he did inspire Edouard Manet and Adriaen Brouwer.

There is this final portrait in the Louvre from 1640 that is signed FH. This painting is sometimes attributed to Judith Jan Leister or F Hals son. It is titled “A Young Man With a Flower” or “La Peintre Ambulant”. The painter is almost certainly not a son of Franz Hals or Fran’s Hals himself despite the similarities.

If you would like to learn more about Frans Hals, there is a Fran’s Hals Museum in Haarlem in the Netherlands. I also stumbled onto a genealogy website that talks about his lineage. The Louvre website has excellent art criticism on all the pieces from their collection. Finally, European Heritage has nice art history on the Dutch Golden Age.