Dragonflies and their relatives are an ancient group. Meganisoptera is an extinct order of very large to gigantic insects, occasionally called Griffinflies. The largest known Griffinfly and/or insect of all time was a predator resembling a dragonfly but was only distantly related to them. Its name is Meganeuropsis, and it ruled the skies before pterosaurs, birds and bats had even evolved. The oldest fossils are of the Protodonata from the 325 Mya Upper Carboniferous of Europe, a group that included the largest insect that ever lived, Meganeuropsis permiana from the Early Permian (300–250 Mya). Meganeuropsis permiana was described in 1939 from Elmo, Kansas. It was one of the largest known insects that ever lived, with a reconstructed wing length of 330 millimetres (13 in), an estimated wingspan of up to 28 inches (710 mm), and a body length from head to tail of almost 430 millimetres (17 in). Nevada designated the Vivid Dancer Damselfly (Argia vivida) as the official state insect in 2009. Sadly, I have no photos of the state insect but Nevada has many eco-zones and the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve has quite a number of equally beautiful species.

Fossils

Controversy has prevailed as to how insects of the Carboniferous period were able to grow so large. The way oxygen is diffused through the insect’s body via its tracheal breathing system puts an upper limit on body size, which prehistoric insects seem to have well exceeded. It was originally proposed in Harlé (1911) that Meganeura was only able to fly because the atmosphere at that time contained more oxygen than the present 20%. This theory was dismissed by fellow scientists, but has found approval more recently through further study into the relationship between gigantism and oxygen availability. Bechly suggested in 2004 that the lack of aerial vertebrate predators allowed insects to evolve to maximum sizes during the Carboniferous and Permian periods (350–250 Mya), could have been accelerated by an “evolutionary arms race” for increase in body size between plant-feeding Palaeodictyoptera and meganeurids as their predators.

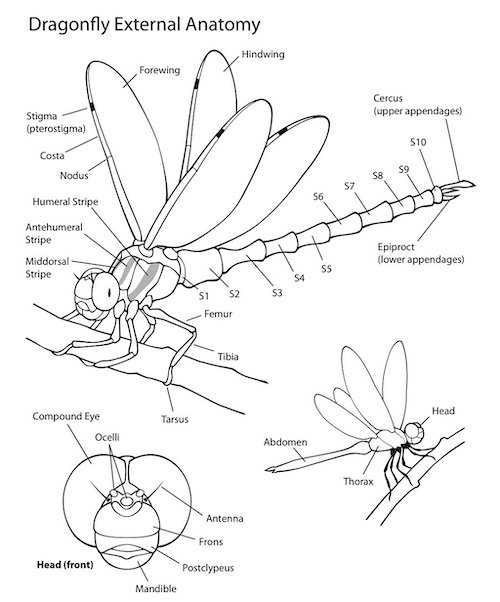

Dragonfly Anatomy

Like all insects, the dragonfly is made up of three main body parts: head, thorax and abdomen. The head is a tough, rounded capsule, hollowed out at the back to allow efficient attachment of the neck and to increase head mobility. The compound eye is composed of nearly 30,000 lenses, which work in consort to provide a rich visual image to the dragonfly. They are sight-based creatures who, with a quick turn of the head, are able to scan 360 degrees as well as above and below. Their two short bristly antennae are thought to function as windsocks or anemometers, measuring wind direction and speed, thereby giving them a method with which to assess their flight. The thorax is the center for locomotion, it connects two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs. It is a muscular powerhouse, controlling head, wing and leg movements. The most obvious feature of a clear, unpatterned wing is the stigma, located on the leading edge of each wing out towards the wingtips. It is thought that the stigma may be used for signaling mates or rivals and may also act as a tiny weight that dampens wing vibrations. The nodus, located at the shallow notch midway down the leading edge of each wing, is an intersection of several large veins and is a point of both strength and flexibility. The abdomen always has ten segments. Segments 1 and 2 appear to be integrated into the thorax and are sometimes difficult to tell from the thorax. To find a particular segment, it is usually best to start with segment 10, far out at the tip, and count backwards. Because of its segmented nature, the abdomen is very flexible and is able to arch up or down (but not side to side).

Dragonflies vs Damselflies

Dragonflies and damselflies are part of the order Odonata (odonates). Insects of the order Odonata are divided in two suborders: Epiprocta (dragonflies) and Zygoptera (damselflies). Three basic differences separate the two, first dragonfly wings are perpendicular to the body at rest while damselflies keep the wings parallel to the body. Also the compound eyes of dragonflies are large and almost touch at the top of the head while damselflies have smaller eyes and there is always a gap of space between them. Finally, dragonflies have bulkier bodies than damselflies, with a shorter, thicker appearance. Damselflies have a body made like the narrowest of twigs, whereas dragonflies have a bit of heft.

Dragonfly Sex

To mate, the male first grabs a female by the back of her neck with claspers at the end of his abdomen — these structures actually fit into species-specific grooves in the female. From here, the pair can fly around together in tandem. If the female is sexually receptive, she will lift her abdomen up to bring her “vagina” in contact with his “penis,” allowing the male to transfer his sperm. In some species, the pair will remain in this wheel position for only a minute. Others, however, may stay in formation for several hours, while the male tries to use spoonlike structures on his penis to scoop out any sperm from other males the female may already have in her. In order to avoid males of the species bothering them for sex, female dragonflies sometimes fake their own deaths, falling from the sky and lying motionless on the ground, upside down, until the suitor goes away.

Blue Dasher

Blue Dashers (Pachydiplax longipennis) are one of the most abundant dragonflies in the U.S. and can be found near still, calm bodies of water, such as ponds, marshes, slow-moving waterways, and ditches, in warm areas typically at low elevations. It is a small blue dragonfly with a white face, a black tip to the abdomen, and a black-and-yellow-striped thorax. Females are recognized by the narrow yellow parallel stripes on the abdomen. Both sexes have an amber patch at the base of each hindwing. Males develop a sky-blue (or Carolina-blue) abdomen when they approach maturity. California specimens turn blue not just over the abdomen (hiding the dark tip), but the thorax as well, and often have no amber on the wings at all. Fully mature males are powdery blue with jade-green eyes.

As they mature the abdomen becomes blue except for yellow that remains on the sides of the first few abdominal segments and the black tip on the end of the abdomen. The eyes at this stage are still juvenile red/grey.

Females have paired yellow stripes on the upper/dorsal side of the first 8 abdominal segments, but not on segments 9 and 10. The end of the abdomen has a yellowish-white tuft in the center. Their eyes retain the half red/brown, half blue/gray color of immatures, though an occasional green-eyed female can be seen. Females are also reported to turn blue with age, but more slowly than males. Older females get somewhat bluish, but never, it seems, quite like the males.

The adults roost in trees at night. These dragonflies, like others, are carnivorous, and are capable of eating hundreds of insects every day, including mosquito and mayfly larvae. The adult dragonfly will eat nearly any flying insect, such as a moth or fly. Nymphs have a diet that includes other aquatic larvae, small fish, and tadpoles. These dragonflies are known to be voracious predators, consuming up to 10% of their body weight each day in food. The blue dasher hunts by keeping still and waiting for suitable prey to come within range. When it does, they dart from their position to catch it.

Flame Skimmer

The Flame Skimmer or Firecracker Skimmer (Libellula saturata) is a common dragonfly of the family Libellulidae, native to western North America. Due to its choice habitat of warm ponds, streams, or hot springs, flame skimmers are found mainly in the southwestern part of the United States. They also make their homes in public gardens or backyards. Male flame skimmers are known for their entirely red or dark orange body, this includes eyes, legs, and even wing veins. The males bright orange/red with amber color in the wings covering half the width of the wing, out to the nodus, and all the way to the rear of the hind wing. Females are paler but still with some amber at least on the leading edge of the wing. Females are usually a medium or darker brown with some thin, yellow markings. This particular type of skimmer varies in size but is generally measured somewhere between 2–3 inches (5–7.6 mm) long.

Mexican Amberwing

The Mexican Amberwing (Perithemis intensa) is a dragonfly of the family Libellulidae, native to the southwestern United States and Mexico. These are small dragonflies, with an average length of 1 inch (25 mm). Males are recognized by their overall amber/orange color. The head, thorax and abdomen are a bit brown, but even these could be described as a shade of orange. The eyes are red. Females have similar bodies, but the wings have two bands of amber/orange with black spots. This skimmer is found in semi-arid regions from California to Texas.

Black Saddlebags Skimmer

The black saddlebags is a relatively large dragonfly at about 2 inches (5 cm) in length. The body is thin and black, and the female may have lighter spotting or mottling dorsally. The head is much wider than the rest of the body and is dark brown in color. The length of the body varies from 2.0 to 2.2 inches. The hindwings are 1/4 covered with a black band, near the body. Females and juvenile males have yellow-brown faces and large white dorsal spots on most of the abdomen. Also females and immatures have yellow spots on S6 and S7. It can be found at bodies of stagnant water, such as ponds and ditches. The female mates once and stores all the sperm she needs for fertilization. If she should mate again, the second male will remove the sperm of the first male from her body with the brush-like apparatus on his specially-adapted penis. The larvae of the dragonflies hatch and eat anything they can catch, favoring a carnivorous diet of organisms smaller than themselves. Adults of the species, especially males, congregate in swarms. They are one of a dozen or so American dragonflies that migrate; the offspring of the northbound Black Saddlebags return to the South, and their offspring come north with the spring. In fall, they join the Common Green Darners that drift along the Atlantic coast and the shore of Lake Michigan.

Twelve-Spot Skimmer

The 12 spotted skimmer is a large showy dragonfly in the skimmer family, measuring 2 inches (5 cm) in length. It looks even larger when flittering around the wetland because of the numerous spots placed along the length of the wing (6 spots on each side with black at the tip, a white spot nearest the tip is the Eight-spotted Skimmer). In mid-summer (July & August), they are very active and territorial often covering the whole wetland or lake shore on patrol and then returning back to the same area. This species is found statewide in ponds, lakes and wetlands with abundant emergent vegetation and oftentimes some open water. Like all adult dragonflies they eat smaller flying insects such as mosquitoes and flies, but will also take down damselflies and moths. Twelve-spotted Skimmers prefer habitats of lakes and ponds, often shallow or semipermanent, as well as slow streams, marshes, and bogs. They are also commonly encountered in open fields where they forage. The twelve-spotted skimmer (Libellula pulchella) is a common North American skimmer dragonfly, found in southern Canada and in all 48 of the contiguous U.S. states. It is a large species, at 50 mm (2.0 in) long. Each wing has three brown spots. In adult males, additional white spots form between the brown ones and at the bases of the hindwings; it is sometimes called the ten-spot skimmer for the number of these white spots.

Roseate Skimmer

Orthemis is a genus of large Neotropical dragonflies, commonly called Tropical King Skimmers. The males are generally red and the females brown. There are two major species in Orthemis. The Roseate Skimmer (Orthemis ferruginea) is a species dragonfly in the family Libellulidae. It is native to the Americas, where its distribution extends from the United States to Brazil. It is common and widespread. It is an introduced species in Hawaii. It behaves similarly to many King Skimmers (Libellula), foraging from the top of tall vegetation. It is an aggressive predator taking insects only slightly smaller than itself. Males will regularly and vigorously patrol territories averaging 10 m. Males use their abdomens to ward off intruding males by bending the tip downwards. Orthemis discolor, known generally as the carmine skimmer or orange-bellied skimmer, is a species of skimmer in the dragonfly family Libellulidae. This one is brilliant pink, sometimes purplish, sometimes more red, with bright red eyes and face. Face and eyes typically as brightly colored or brighter than the body; compare to Roseate Skimmer, in which the eyes and face are usually darker than the body. It is quite similar to Roseate Skimmer, but has a brighter red face and eyes. In some cases, in-hand ID may be necessary to separate these similar species. The white stripe on the back may indicate a more rare species.

Bluetail Fronted Dancer

The Blue-Fronted Dancer (Argia apicalis) has a wide distribution in North America, its range extending from Ontario in Canada, across the United States except for the extreme southwest, to the state of Nuevo León in Mexico. It inhabits a range of habitats including near large and small rivers, streams, lakes and ponds, but is most common in the vicinity of large, muddy rivers. ranges in length between about 33 and 40 mm (1.3 and 1.6 in). Most males have a blue thorax, the plates being separated by a few black lines, and also have a color-tipped abdomen, segments eight, nine and ten being bright blue. The remaining segments are dark brown. However the color of the thorax of Argia apicalis is variable and some males can be greyish-black rather than blue. They can change from one phase to the other and back again over the course of several days, with several intervening variations on the way; neither color phase seems to be particularly related to age or sexual maturity.

Females exhibit three thoracic color phases: brown, turquoise and grayish-black. Again the phase change often takes place in steps, and none of the phases seems to be associated with a particular age or state of maturity.

Vivid Dancer Damselfly

As always, I hope you enjoyed the post and will return in the future. I will add more photos as I get them in the future.

References:

Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve

Trinidad and Tobago Bees, Butterflies and Bugs

Animal Sex: How Dragonflies Do It

Female Dragonflies Fake Death to Avoid Males Harassing Them for Sex

Dragonflies and Damselflies of Nevada

Dragonflies. DesertUsa Kathy Biggs

Do Dragonflies Bite or Sting People? Here’s Why They’re Typically Harmless

Swarms of Dragonflies from Space

Dragonflies Embark on an Epic, Multi-Generational Migration Each Year