Like the rest of the world, for the past several months I have been preoccupied with the pandemic, resulting in a loss of concentration and writers block. A great diversion for me during these trying times has been a local bird watching area, the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve. Each morning I cast the worries of the world aside and walk for a few hours with my camera, photographing birds and interesting plants. I have accumulated quite a nice number of photos and I thought they would make a good series of posts. I find it interesting that while I have written extensively about my travels, It has taken a pandemic to make me really see the attractions in my own backyard, so to speak. Over the years I have often traveled to riparian areas near rivers and lakes to observe birds but over the past few years more and more trips centered on wastewater treatment ponds. Due to clean water legislation in the US, these ponds have become ubiquitous and provide really great birding opportunities in most areas. I thought I would spend a little time exploring ecological wastewater treatment, particularly since cholera was a recurring pandemic of the 19th century, and then describe the plants and animals associated with these areas. Interestingly, one of the foremost tenets of modern treatment ponds is to utilize local native plants. Thus these facilities are not only a great place to see birds but also provide a unique presentation of often unusual or endangered native plant communities. This post is meant as an introduction to the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve while future posts will focus on specific plants, animals, birds and bugs.

Cholera and Wastewater Treatment

People in 19th century London and across the world were dying from cholera. There were at least 6 waves of cholera which washed around the world in the 1800’s. The third cholera pandemic (1846–1860) deeply affected Russia, with over one million deaths. A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives. In 1849, a second major outbreak occurred in France. In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city’s history, claiming 14,137 lives. In 1854 there were 500 deaths from cholera within 10 days. Dr. John L. Snow, the father of modern epidemiology, proved that the cholera outbreak was a result of bacteria in the drinking water in 1855. His discovery led to a restructuring of the sewage system and an incorporation of chemical sanitizing. London was one of the first places in the world to use chlorine bleach to disinfect drinking water. The result was a great reduction in the number of deaths from cholera. Sadly, most of the world continued to dump their raw sewage directly in rivers, lakes and oceans thus contaminating the drinking water of those downstream. In the United States, the first sewage treatment plant using chemical precipitation was built in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1890. Most cities in the Western world added more expensive systems for sewage treatment in the early 20th century, after scientists at the University of Manchester discovered the sewage treatment process of activated sludge in 1912. Since the early 1970s, waste water quality in the United States has improved through Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTWs) and through major investments contrived by the Clean Water Act. Wastewater treatment facilities in the United States process approximately 34 billion gallons of wastewater every day. Wastewater contains nitrogen and phosphorus from human waste, food and certain soaps and detergents.

Constructed Wetlands

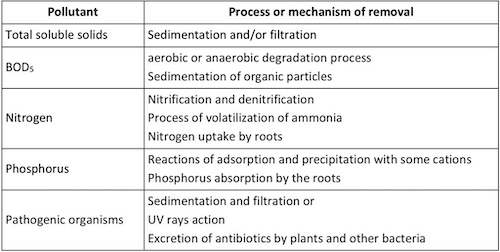

Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment have developed in the last few decades as an alternative to costly industrial methods. Essentially, carefully selected native plants both in and near the water absorb nitrogen, phosphorus and toxins, naturally cleansing the water like magic. Wetlands work through a combination of microorganism interaction, plant and soil filtration, aeration and settling to remove particulates and contaminants. As an eco-friendly treatment process, constructed wetlands enable the effective, economical, and ecological treatment of agricultural, industrial, and municipal wastewater. Constructed wetlands (CWs) have been proved to be “cost-effective” methods for wastewater treatment, with savings up to 92%. They also provide other landscape and social benefits such as wildlife habitat, research laboratories, and recreational uses. CWs are artificial wetland systems that are designed to exploit the physical, chemical and biological treatment processes that occur in wetlands and provide for the reduction in organic material, total suspended solids, nutrients, and pathogenic organisms.

Algae Blooms

In our hot summers the ponds often get an algae bloom due to increased nitrogen and phosphorus in the water as seen in the above photo. Algae blooms can remove oxygen in the surrounding water, often killing fish and are considered a bad thing in water sources. In a stream, lake or ocean this would be a catastrophe, causing wholesale death of aquatic life and disruption to the local ecosystem. In settling ponds, the bloom is controlled, self limited and isolated, the reeds provide extra oxygen and the algae bloom provides food for ducks, geese and other waterfowl. Algae is not always bad. Algae have been used to provide food for people and livestock, to serve as thickening agents in ice cream or shampoo, and can be used as drugs to ward off diseases. More than 150 species of algae are commercially important food sources, and over $2 billion of seaweed is consumed annually by humans, specifically in Japan.

Quail Bush

At the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve, they have planted quite a lot of Quail Bush for its hardiness, it’s detoxification properties with respect to wastewater and for ground cover used by many animals. Quail Bush or Big Saltbush is native to the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, where it grows in habitats with saline or alkaline soils, such as salt flats and dry lake beds, coastline, and desert scrub. Bladders in the leaves act as salt sinks that keep salt from the plant cells and allow the plant to extract water from the soil. During the summer, the plant produces large bracts of flowers which will produce small, red seeds. Quailbush provides cover for quail, other game birds, and song birds. Rabbits increase where plantings of this species have been established. Small mammals, lizards, rattlesnakes, coyotes, quails, and other birds use the seeds and foliage for food and habitat. Foliage and twigs provide shelter for small mammals and livestock. All of the quail bush plant is edible. Young shoots can be used as cooked greens before they get hardy. The leaves have a nice salty taste, so you won’t need any additional sodium in your meals if you use this plant. Fresh leaves are especially delicious in salads, sandwiches, and bruschettas.

Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 was the first major U.S. law to address water pollution. Growing public awareness and concern for controlling water pollution led to sweeping amendments in 1972. As amended in 1972, the law became commonly known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). For more than 20 years, local birders and nature lovers have visited the evaporating ponds at the Henderson Wastewater Reclamation Facility. As the third-largest body of water in Southern Nevada, the ponds proved irresistible to a wide variety of native and migratory birds. Here in the middle of a desert, birds found an undisturbed and plentiful water source. In 1967, the water reclamation site was first included in the National Audubon Society’s Christmas Count. Each year, the local chapter provided information on the number of types of birds to the National Audubon Society Headquarters in New York City. The information was used to track how well different bird species were faring. Some bird species identified were migrating to the tip of South America and back each year. The ponds were also used as a part of a nationwide shorebird survey conducted by the Point Reyes Bird Observatory in northern California. In December 1996, the first official meeting took place between representatives of the city’s Department of Utility Services, Red Rock Audubon Society and Montgomery Watson Engineers, a firm that had performed much of the facility’s engineering. The group discussed their vision for a bird viewing preserve. They saw an opportunity to provide the public with a venue to see and learn about birds, and to create a bird habitat that provides naturally occurring food sources for resident, migrating and nesting birds. And they saw an equally appealing opportunity to educate preserve users on wastewater treatment and ecology. On May 20, 1998, the City of Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve was officially dedicated and became “A Place to Call Home” for more than 270 species of birds – and thousands of bird lovers.

Frenchman Mountain

Frenchman Mountain is the highest peak in the craggy mountain range that forms the eastern border of the Las Vegas Valley. The range is composed of two peaks: Sunrise Mountain to the north and Frenchman Mountain to the south. It is a rocky, treeless ridge visible from everywhere in Las Vegas and a formidable and beautiful landmark throughout the Henderson Bird Watching Preserve. The mountain rises about 1500’ to 2000’ above the surrounding desert. The Las Vegas Wash, located in front of Frenchman Mountain, is a 12-mile-long channel which feeds most of the Las Vegas Valley’s excess water into Lake Mead. The wash is sometimes called an urban river, and it exists in its present capacity because of an urban population. The wash also works in a conjunction with the pre-existing wetlands that formed the original oasis of the Las Vegas Valley. The wash is fed by urban runoff, shallow ground water, reclaimed water, and stormwater. In addition, during rains, significant water flows down Frenchman Mountain into the wash.

Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve in Winter

Winter is a period of rest and regeneration in the Bird Viewing Preserve. The many plants, both in and around the water, often die back during winter and the maintenance staff is kept busy pruning dead branches and removing dead leaves. This removal of dead material is important to the underlying mission of the settling ponds to clean the wastewater. In order to continue their purification duties, the plants must remain healthy and vibrant. Dead material may contain heavy metals and other impurities that were removed from the water when the plants were alive. In addition, winter is a great time for birdwatching since the trees are often bare of leaves, revealing the birds. Also winter brings birds from farther north who may winter in Las Vegas. In this area just a little northwest, bordering on the Las Vegas Wash, is the Clark County Wetlands.

Riparian Ecosystems in the American Southwest

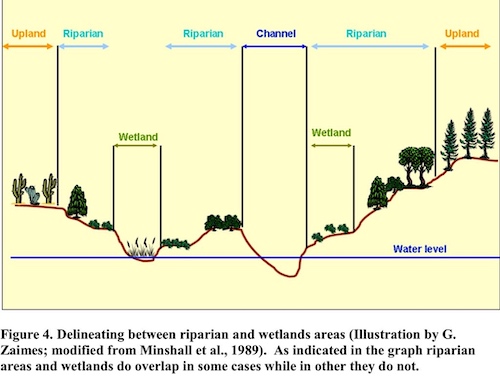

Although they constitute less than 2% of the land area in the American Southwest, riparian habitats support the highest density and abundance of plants and animals of any habitat type, making them critical to the ecological integrity of this large area. Riparian areas supply food, cover, and water, and serve as migration routes and habitat connectors, for a variety of wildlife. They also help control water pollution, reduce erosion, mitigate floods, and increase groundwater recharge. Riparian systems perform numerous ecosystem functions important to human populations, yet are one of the most endangered forest types in the United States. Riparian areas along southwestern rivers have among the highest densities of birds for the United States, and although cottonwood-willow gallery forests are of special interest to ecologists, mesquite bosques have been a neglected critical habitat for birds. Riparian ecosystems are made up of the plants and animals living along lakes, rivers, and streams, and the soil, air and water that support them. They include areas within floodplains that may only rarely see surface flows, but where the “water table” (top of the aquifer, below which the ground is saturated) is shallow enough for plant roots to reach subsurface water.

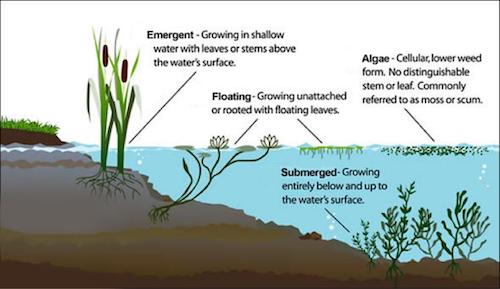

Littoral Zone

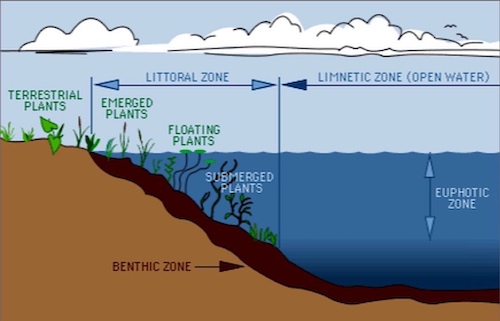

A typical lake has distinct zones of biological communities linked to the physical structure of the lake. The littoral zone is the near shore area where sunlight penetrates all the way to the sediment and allows aquatic plants (macrophytes) to grow. Light levels of about 1% or less of surface values usually define this depth. The 1% light level also defines the euphotic zone of the lake, which is the layer from the surface down to the depth where light levels become too low for photosynthesizers. In most lakes, the sunlit euphotic zone occurs within the epilimnion (top-most layer in a thermally stratified lake). The limnetic zone is the open water area where light does not generally penetrate all the way to the bottom. The bottom sediment, known as the benthic zone, has a surface layer abundant with organisms. This upper layer of sediments may be mixed by the activity of the benthic organisms that live there, often to a depth of 2–5 cm (several inches) in rich organic sediments. Most of the organisms in the benthic zone are invertebrates, such as insect larvae (midges, mosquitoes, black flies, etc.) or small crustaceans. The productivity of this zone largely depends upon the organic content of the sediment, the amount of physical structure, and in some cases upon the rate of fish predation. Native plants consume nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus. The weeds and algae also consume these nutrients. When most of the nutrients are being absorbed by the native plants, there will be less algae in the ponds. With proper maintenance of a littoral shelf, the water quality will continue to improve and stay improved. Wildlife habitat will also benefit from maintenance which involves removing dead material.

The Ponds

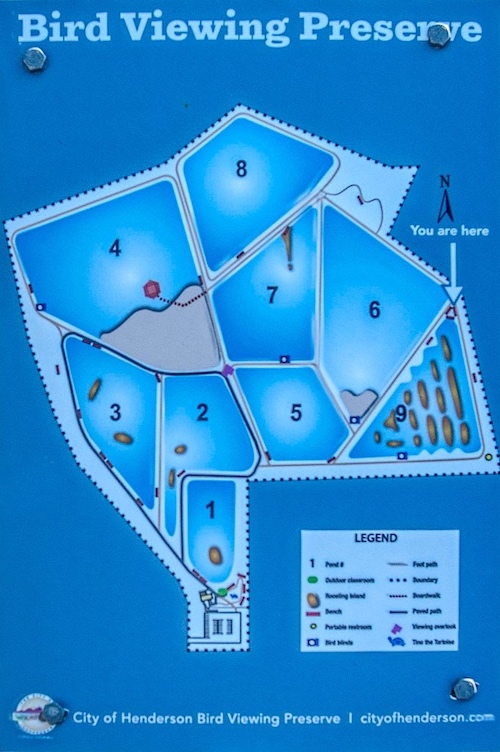

I am a lover of gardens, large or small, structured or wild, and I am particularly interested in how they came to be. All living things have a hidden structure, we have bones, and gardens are no exception. Some of the structures are imposed by our plantings and others are mysterious, unexpected growth and flowering that can delight and astound us. The bones of this ambitious garden began with the intent to purify water, not by a contrived mechanical contraption but by the magic of nature. Each of the ponds is at a different height, with pond 1 at the highest position. As pond 1 fills, the overflow goes to adjacent ponds through pipe spillways, skimming the purest water from the top. Each pond is surrounded by patch-work plantings of the three riparian plant communities of the Sonoran desert, cottonwood/willow gallery forest, “cienega” or marsh, and mesquite “bosque” or woodland. Of course, each of those “type” plant communities have many more plant members which I will detail in future posts. For now I want to describe the result of the plantings as they relate to birds for each pond.

Pond 1

Pond 1 is the “marquee” pond, the first pond visitors see as they exit the visitor center. The plantings are lush, there is lots of shade and seating in the form picnic tables, benches and even a small outdoor classroom. They have hummingbird feeders, a desert tortoise and quite a few Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps) in the trees since they feed them nectar. There is a broad shallows area directly behind the visitor center which often features wading birds, ducks, grebes and Killdeer. Even the occasional snake takes advantage of the shallow water. This is the top pond and the water inlet at the northwest corner often has a collection of waterbirds.

Pond 2 and 3

Gallery forests of Cottonwood (Populus fremontii) and Willow (Salix gooddingii) historically were one of the most abundant riparian ecosystems along low-elevation rivers of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, and now are among the most threatened forest types in the United States. Plantings along the east side of the preserve are particularly rich in Cottonwood and Willow, including ponds two, three and four. In addition, all of these pond have islands which are favorites for nesting. This area seems particularly suited to heron and egrets, many of whom I have seen in this area.

Pond 4

Pond 4 is one of the larger ponds in terms of area and it is home to a diverse number of habitats. On the south side is the elevated walkway leading to a shallow lagoon lined with willow and cottonwoods with an island nearby. Here you will find many smaller birds, often migrating on their way to somewhere else. Sadly, though the shallow lagoon is beautiful to see, I have rarely seen wading birds there. Perhaps the people coming for the viewing platform scared them away. The south side also has a floodplain, filled mostly with quail bush, that is home to several Roadrunners, Gamble’s Quail, Verdin and a variety of reptiles. The northeast corner has a wading area for waterbirds which is used heavily.

Pond 5

Pond 5 is mostly notable for the elevated viewing platform and for being in the relative center of the preserve, although there is rarely much to observe as the platform is a magnet for loud children and groups. There are always Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) around, noisily announcing their presence and Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps), Black-Headed Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans), Great Tailed Grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) and Yellow-Headed Blackbirds (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) in season.

Pond 6

Pond 6 is one of my favorites, really divided into two attractions. the south end has a wading area with a blind, a good place to see wading birds like Avocets (Recurvirostra americana), White-Faced Ibis (Plegadis chihi) and Snowy Egret (Egretta thula). The north side, bordering on the rather desolate Las Vegas Wash, has a Mesquite bosque with lots of Verdin (Auriparus flaviceps), Black-Tailed Gnatcatcher (Polioptila melanura) and Say’s Phoebe (Sayornis saya). Also a good number of reptiles, roadrunners and extremely cute Harris’ Antelope Squirrels (Ammospermophilus harrisii).

Pond 7

Pond 7 is a pond between more interesting ponds. There are not a lot of viewing points to the water and not any particular attractions. I did see a Gilded Flicker (Colaptes chrysoides) on one side (I can’t remember exactly where) so there are birds, often just difficult to see them.

Pond 8

The northern edges of Pond 8 border the relative desert of Las Vegas Wash and have birds similar to the Mesquite Bosque of Pond 6. The difference is the Salt Cedar (Tamarix ramosissima) lining the fence, which the birds seem to love but is a headache for the maintenance staff at the preserve. Since this area is the interface between open desert and the bird preserve, there are a fair number of interesting birds and animals. On the northeast corner there is a floating raft that usually attracts ducks and waterfowl. This is the other big pond, making photography of the water birds a little more difficult.

Pond 9

If you a migratory bird, new in town, Pond 9 is probably the best place. With lots of islands and reeds, the birds have a little privacy and plenty to eat. On the north side it borders on the Las Vegas wash. On this side there is a strip of open water that often has interesting birds. On the east side, migrating birds like to rest, high in the trees. For instance, this summer we have a group of 9–10 Double-Crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus) spending time in the trees. The island in the center is very popular with the birds but viewing angles and the distance makes photography a bit difficult.

As always, I hope you enjoyed the post. This got quite a bit longer than I anticipated but with the pandemic, I have a lot of photography to share. If you visit Las Vegas and love birds or just enjoy some nice scenery, consider a visit to the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve.

References:

Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve

History of the Clean Water Act

A Consumer’s Guide to Wetland Wastewater Treatment

US Wastewater and Sewage Industry

Selection of Plant Species in Wastewater Treatment

Spring Birds in the Arcata Marsh

Ground Cover in the Las Vegas Washes

Mesquite Bosques: Not Just A Bunch Of Trees!

Understanding Arizona’s Riparian Areas

Effects of livestock management on Southwestern riparian ecosystems

US rivers and lakes are shrinking for a surprising reason: Cows