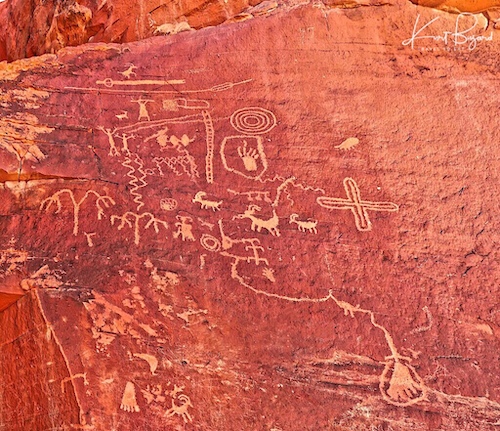

If you visit Little Petroglyph Canyon, you will inevitably ask who created these petroglyphs. The short answer is, nobody knows who made them or in fact, how old they are. The Coso people were inhabiting the Coso area when the Europeans first arrived but there were only about 150–250 Coso people in the area and they claimed to know nothing about the petroglyphs. Over the past 100 years significant effort by anthropologists and archeologists have worked on clues from the past to explain the entrance of humans into the Americas and what they did once they were there. Since it was a long time ago, many things have been washed away by time. However, looking at stone tools, pollen counts from pack rat middens, linguistics and retained native customs we have a hotly debated but reasonable idea of how things changed over time for the Coso people and humans all over the Americas. This post is an overview of this work and while it will not tell you the who and when the petroglyphs were made, it will give you context to decide for yourself. I think you will be surprised at the ultimate influence this tiny, out of the way place, had on the entire southwest.

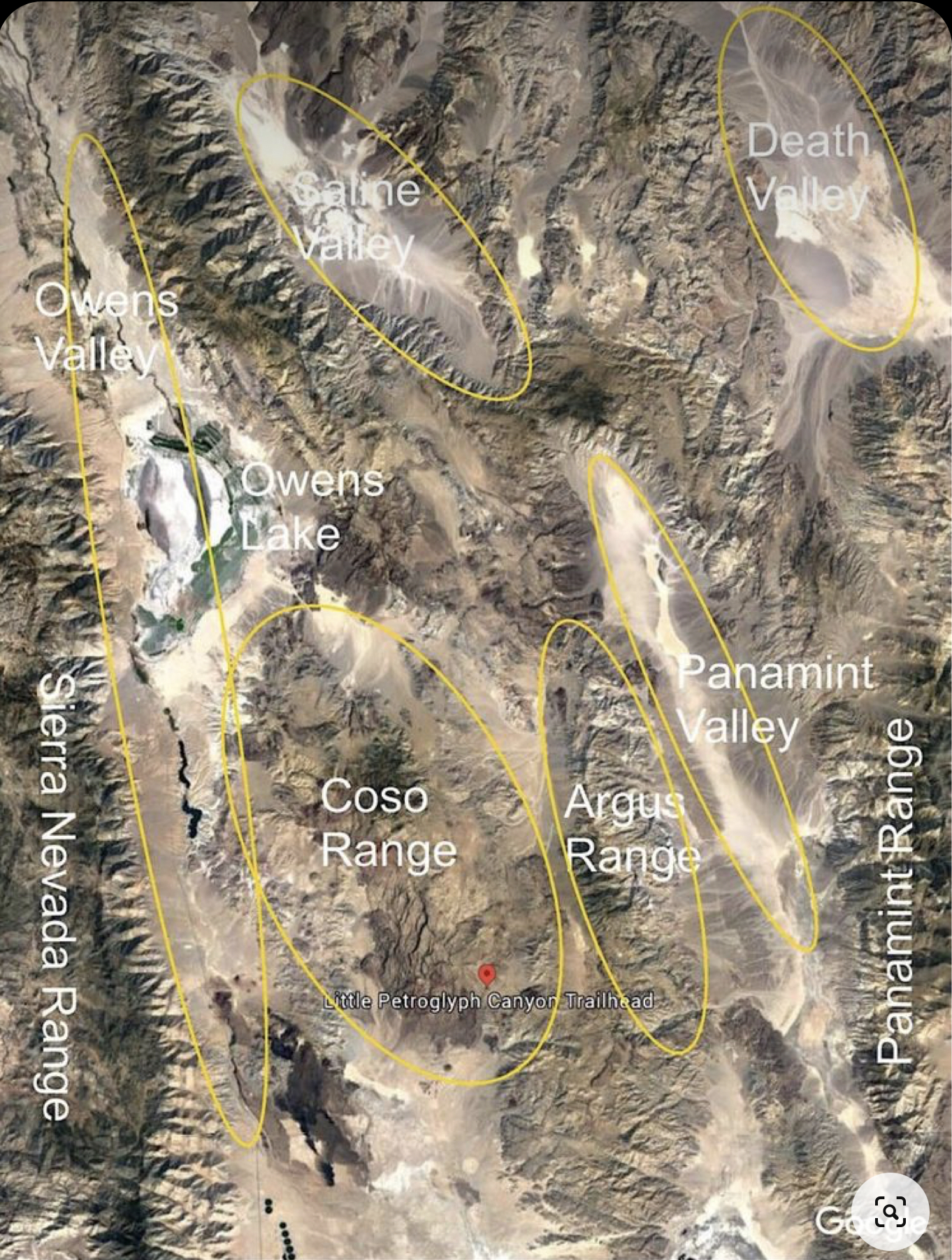

Maps

I have included the above maps to give you a basic idea of where this canyon lies. The Coso Range lies between the Sierra Nevada Range to the west and Death Valley National Park to the east. Due west is Sequoia National Park and beyond that, Tulare and the San Joaquin Valley. To the east lies a small valley, the Coso Valley, and then the Argus Mountain Range. The Argus Range is one of the westernmost of the Basin and Range Province ranges. The northern end of the range is just south of the Panamint Springs Resort on Highway 190. The range runs south to Argus Peak, just northwest of Searles Lake, near the town of Trona, California. In addition to Argus Peak, the range contains Maturango Peak, the highest mountain in the range. Beyond the Argus Range going west is the Panamint Valley and Range, followed by Death Valley on the western side of the Panamint Range. To the north of the Coso Range is the Owens River in the Owens Valley and Owens Lake, a fertile agricultural area for thousands of years, used by the Owens Valley Paiutes. To the south is the the Searles Valley, Mohave Desert with Barstow and Baker, Mohave Valley and further south, Joshua Tree National Forest with the Pinto Basin. Another feature of note is the Mohave River which today is mostly underground, running from the eastern San Bernardino mountains all the way to Primm, which made the communities of Barstow and Baker possible.

Coso/Numic People

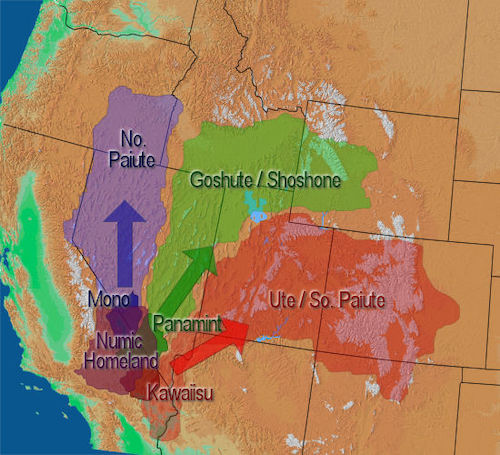

Linguistically all of the indigenous people of the Great Basin, with the exception of the Washo, spoke languages which belong to the Numic division of the Uto-Aztecan language family. The Numic languages appear to have divided into three sub-branches-Western, Central, and Southern-about 2,000 years ago. Numic is a branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It includes seven languages spoken by Native American peoples traditionally living in the Great Basin, Colorado River basin, Snake River basin, and southern Great Plains. Apart from Comanche, each of these groups contains one language spoken in a small area in the southern Sierra Nevada and valleys to the east (Mono, Timbisha, and Kawaiisu), and one language spoken in a much larger area extending to the north and east (Northern Paiute, Shoshoni, and Colorado River). Some linguists have taken this pattern as an indication that Numic speaking peoples expanded quite recently from a small core, perhaps near the Owens Valley, into their current range. This view is supported by lexicostatistical studies. Fowler’s reconstruction of Proto-Numic ethnobiology also points to the region of the southern Sierra Nevada as the homeland of Proto-Numic approximately two millennia ago, perhaps as long as 3500 years ago. Recent mitochondrial DNA studies have supported this linguistic hypothesis. The word Numic comes from the cognate word in all Numic languages for “person.” For unexplained reasons, some time around 1000 A.D., all three of the Numic groups began once again to move and expand. Fanning out from their central locations in southern California, these three groups moved northeasterly; but they remained on the edge of the Great Basin until about 1050 A.D. Coincidentally, this was essentially the same time that the Fremont and Anasazi began to decline. When that happened, the Numic tribes moved rapidly into the Great Basin and eventually onto the neighboring Colorado Plateau, displacing the Fremont and Anasazi that had lived there for many centuries. In addition to the above mentioned people the Utes of Utah, Colorado and New Mexico and the Comanche of the Great Plains spoke Numic languages.

All of this complicated language talk can be simplified to say that virtually all of the Native People of the Great Basin, when the Europeans arrived, shared not only variants of the same language but also had a shared belief system, similar customs and similar lifestyles. Much of the subsistence of all the Great Basin Indian tribes depended on the gathering of wild plants. It is estimated that 30 to 70% of the Great Basin diet was based on plants. Several major groups of plants were important to the subsistence of the Great Basin peoples. These include piñon nuts, mesquite, acorns, agave, camas, sego lily, tobacco root, yampa, biscuitroot, bitterroot, cattails, and berries (wolfberry, buckberry, chokecherries). Additionally, they also shared similar images and subjects in their Rock Art. Conversely, the Coso People likely had trading ties, visits and conflicts from both the east and west with possible joint hunts with many other tribes, likely speaking similar but different languages.

Lifestyle, Diet and Culture

After about 1500 years ago an important change in milling technology was a much increased use of bedrock grinding surfaces/cupules and mortars. Thousands of these are found throughout the Eastern Sierra, where people gathered and processed seeds and nuts although they are found in only three locations in the Coso Range. They were located where suitable stone outcrops were present near rich resource areas. A final change was the development of large threshing floors and roasting pits to mass process seeds and pine nuts. This increased the size of the harvest and number of people who could be fed off the land. Generally the bedrock mortars were used more for nuts while seeds were processed on grinding stones, some of which were actually carried around.

As shown above. I believe this configuration functioned much like a grater for fibrous root crops. A group of plants that became more important in the Late Prehistoric period were wild root crops. These included nut grass, cattail, bitterroot, and probably others. Nut Grass is a common weed in many people’s lawns and gardens, but its tubers have been eaten by people in many parts of the world. In the Eastern Sierra , it was gathered from wild stands in wetter parts of the valleys and eventually irrigated to increase its abundance. Other crops like bitterroot (seen above) were gathered at high elevation camps in the mountains, where earlier people spent little time. The bitter root played a part, though a small and inconspicuous one, in that epic of American exploration, the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It was the specimen taken from the herbarium of Meriwether Lewis that was first described by the botanist Pursh and named Lewisia rediviva.

The oak represented a stable food source because acorns could be stored for extended periods. Black oak acorns were preferred over other oaks by Miwok, Mono Lake Paiute, and Western Mono peoples. Black oaks don’t consistently produce good crops of acorns in good years, each family might collect and store about 2,000 pounds of acorns for use over the next several years. Yosemite Valley supports some of the best black oak woodland in the Sierra Nevada, and early people lit fires regularly to maintain them. Fires killed young pines and cedars that could outgrow and overshadow the oaks. The chuckah was the Ahwahneechee’s pantry. Each chuckah could hold several hundred pounds of acorns, providing a substantial part of a family’s diet throughout the year. People built chuckahs with sloping tops to shed rain and snow and lined them with aromatic plants that naturally repel insects. Pounding rocks or bedrock mortar are ideal for pounding acorns. Shallow mortar holes, like the ones shown in the picture, were preferred for processing black oak acorns, while deeper holes were used for manzanita berries. Yosemite’s early inhabitants transported food, medicine, raw materials, and culture throughout the Sierra Nevada and California. To the west, they traded for clamshells, dried fish, and beads. In summer, they traveled east to the High Sierra where they exchanged acorns for salt, pine nuts, obsidian, and alkali fly larva (which they made into high-protein flour), perhaps with the Coso people or more likely with the Owens Valley or Mono Paiutes.

The pine nut was to the people of the Great Basin what the buffalo was to the plains people. The nut is protein packed with all 20 amino acid and very high in concentration in 8 of the 9 amino acids necessary for growth. When pine nuts ripened in the late summer, families moved to the pinyon woodland on the lower mountain slopes. Pine Nut Camps served as places where everyone worked to gather and store nuts for the coming winter. If the harvest was good, families might spend the winter in the woodlands, or return to valley settlements and retrieve their nuts as needed. Such sites are often marked by small rock rings that served as storage areas (see above) for nuts left in the uplands. The pine nuts are gathered in September and October. The cones require two years to mature, so careful observation of the cones means that the scarcity or abundance of the crop can be predicted a year in advance. One of the common ways of collecting the pine nuts was to collect the cones just before they were about to break open. Using poles, the men would beat the trees to get the cones to drop. Then, using a stone hammer or a stick, the cones would be broken open to collect the seeds. Another way of collecting the pine nuts was to pick the seeds from the forest floor after the cones had dried and opened on the tree. This was, however, both labor intensive and time consuming. Prior to European contact, a typical Shoshone family could gather about 1,200 pounds of pine nuts in the fall and this would last the family for about four months.

As with other tribal groups in the Great Basin, wild plants were an important food and fiber source for these groups. Among the Southern Paiute, for example, seeds were gathered from at least 44 different species of grass. Among the Owens Valley Paiute, seed areas were owned by the band. Women would gather the seeds using a small, paddle-shaped basket which they would use to knock the seeds into a conical container. The seeds would then be winnowed, parched with hot coals, and ground on a flat stone. The seed flour could then be prepared as mush or used for making bread. Among the Owens Valley Paiute, ditch irrigation of wild plants was used to increase the yields. Brush dams were used to divert the water into ditches which ran for miles and which watered multi-acre plots. “Paa” ute means water ute, and explains the Southern Paiute preference for living near water sources. The Spanish explorer Escalante kept detailed journals of his travels in the Southwest and made notes concerning Southern Paiute horticulture, writing in 1776, that there were “well dug irrigation ditches” being used to water small fields of corn, pumpkins, squash and sunflowers.

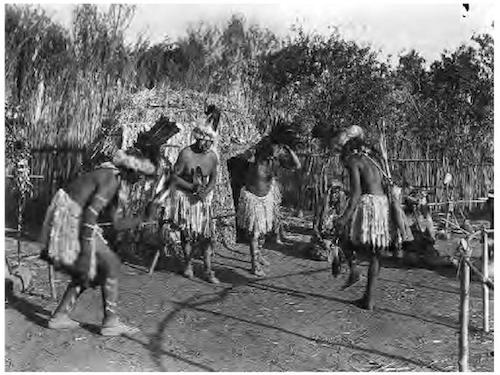

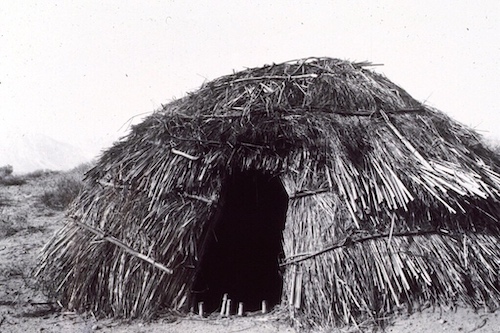

Depending on the time of year and weather, brush made kahns (Paiute for home) or teepees provided shelter. Both shelters can be seen in this photo of a Kanosh band family of Southern Paiutes from Utah. Historically, the tipi has been used by indigenous people of the Plains in the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies of North America, not the native people of the great basin. The introduction of the horse and greater interaction between settled areas led to the adoption of the tipi or teepee by the Numic speaking people of the Great Basin.

In less mobile Native American cultures, such as Anasazi, Fremont and Pueblo, fired clay pottery vessels were used to transport water, for cooking and to store food. The Numic speaking people of the Great Basin had to get creative to find lightweight alternative solutions to each of these functions. The answer was tightly and finely woven baskets, coated with pine pitch to carry water. They could even cook in these vessels, as noted above, by placing hot rocks into a grain or nut mush. Surprisingly, the Owens Valley Paiutes used pottery since about 1300 AD. It was a brown ware, characterized in part by coil-and-scrape shaping and relatively uncontrolled firing. Owens Valley brown ware has been identified both east of the Sierra Nevada and on the western slope of that range. Heavy soot on the exterior walls and carbonized food residue on the interior suggest that these vessels were primarily used to cook food.

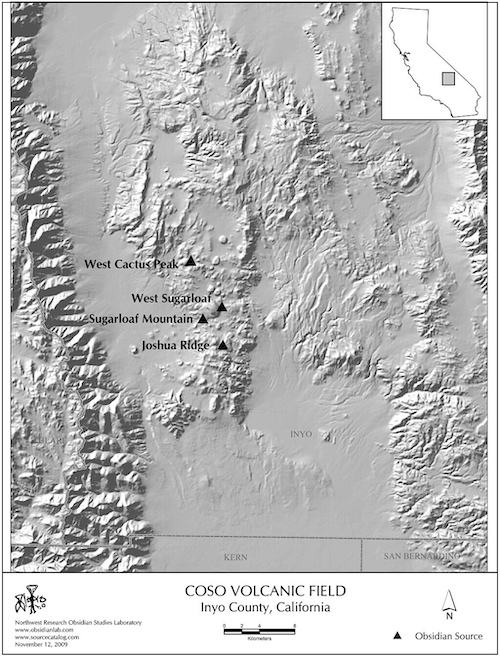

Obsidian in the Coso Mountains

Obsidian from the Coso Volcanic Fields was heavily exploited by Native American People to make knives, projectile points, and other stone tools. The chief period of exploitation was between approximately 3000 and 1000 years ago, when people mined obsidian by constructing benches in hillsides and digging deep pits to access raw materials (Elston and Zeier 1984; Gilreath and Hildebrand 1997). Obsidian from the volcanic fields was traded all the way to the California coast in San Diego, San Luis Obispo County, Santa Barbara, California, and throughout the Mojave Desert and regions further east. Archaeologists recognize at least four different geochemical subsources: Sugarloaf, West Sugarloaf, Joshua Ridge, and West Cactus Peak. Obsidian from the Coso mountains was used and loved by native people for thousands of years, it was a valuable commodity.

Coso Native People

The Coso Indians lived within the Inyo, Coso, Argus, Panamint and Funeral Mountains. These mountains border Saline Valley, Death Valley, and Panamint Valley today. In the mid 1800s, the tribe was settled on Cottonwood Creek in the northwestern area of Death Valley, south of Bennett Mills on the eastern side of the Panamints, at the mouth of Hall Creek in Panamint Valley, and on the west side of Saline Valley near Hunter Creek at the foot of the Inyo Mountains. Their population was small when settlers arrived, with an estimate of 150–250 in 1883. The Coso Indians lived south of the Owens Valley region which was inhabited by the Paiute and Mono tribes. To the west, the Tubatulabal tribe inhabited the Kern River area. To the northwest the Miwok tribe lived in north-central California, from the Pacific coast to the west slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains including Yosemite. The Coso were also thought to be related to the Shoshone & Comanche, which covered a large area from the Sierras to the Platte River in Colorado area and into the Texas region. On the south, the Kawaiisu and Chemehuevi ranged over a similar barren habitat of the desert. The Coso Indians, though resident in the area of the Coso Petroglyphs, had apparently lost the knowledge of why they had been made and for what purpose. Perhaps the Indians that lived in the area chose not to convey their significance to the white settler, the tradition itself had vanished by that time, or most likely the petroglyphs had been constructed by another long-gone Indian group.

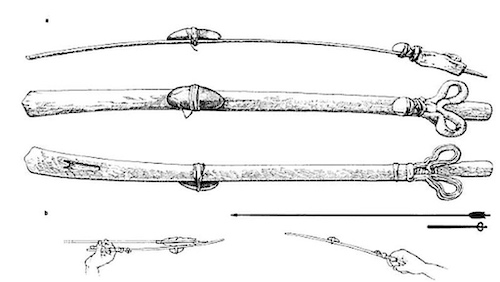

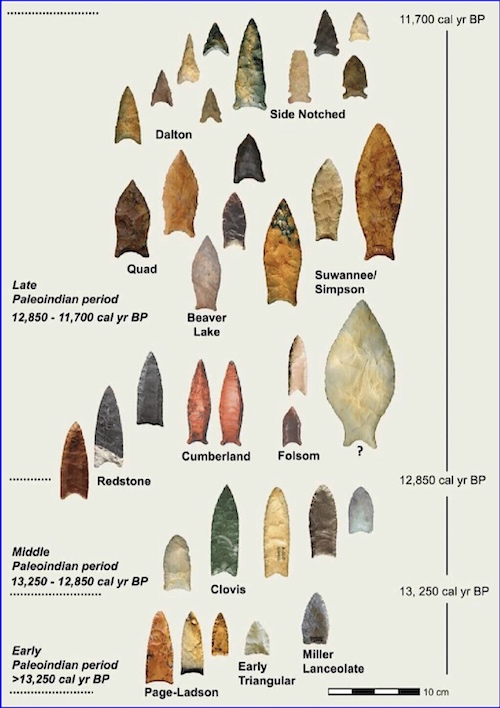

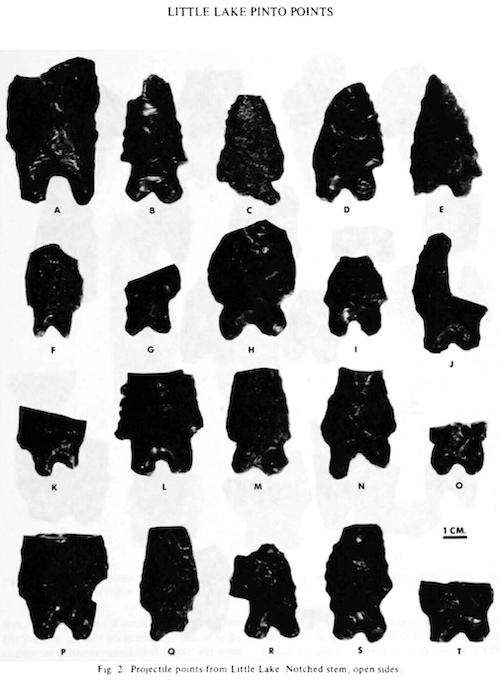

Woven baskets were covered with pitch in order to hold water. The main food was Pinyon nuts, with seeds gathered by beating. Chia and grass seeds were collected, with small game limited to ground squirrel, rabbit and the then occasional big horn sheep as the chief big game. On the shores of Owens Lake countless grubs of fly larvae were scooped out of shallow water, and dried for food. Estimated dates for the arrival of the bow and arrow in the Great Basin have ranged from 4,500 B.P. to 1,300 years BP, while at Coso, it arrived about 1500 years BP. Willow, greasewood, juniper and sinew were used in the making of bows and arrows, with obsidian used as scrapers, points and ceremonial tools. Before the bow and arrows, people used the altatl to propel spears and darts. Atlatl is an Aztec word for what’s also called a throwing board or spear thrower. The altatl was probably used in conjunction with the bow and arrow for a time, especially with the eskimos. Looking at the projectile points pictured above, you see the larger points are for spears, probably used with an altatl and the smaller ones are arrowheads.

Climate Change in Owens Valley

During the last ice age (115,000 – 20,000 BP), the peaks of the Sierra Mountains were not covered, but there were glaciers in the valleys, specifically in the Owens Valley. The glaciers of the Sierras were not connected with the Wisconsinian continental glacier but formed independently. The Tioga was the least severe and last of the three Wisconsin Ice Age Episodes. It began about 30,000 years ago and reached its greatest advance 21,000 years ago. As the Owens Valley glacier melted it left a string of lakes that resulted as one after the other overflowed. The Owens valley was a very different place then. During the full-glacial, Owens Lake was located in a transitional position between the full-glacial single-needle pinyon-juniper woodlands of the Mojave

Desert and the Utah juniper-limber pine woodland of the southern Great Basin. Lake levels at Lake Searles (downstream from Lake Owen) were generally high to overflowing between 25,000 and 10,000 years before present (BP). Between ca 21,000 and 15,000 yr BP a continuous highstand is inferred. This means the Owens Valley probably remained forested until at least around 10,000 yr BP. During a lengthy period beginning around 5,000 BCE, an episode of intense climatic warming was responsible for major changes in human settlement patterns and lifeways. The large lakes dried up and their associated resources were gone. Inhabitants were forced to seek living sites near dependable water sources: springs, streams, or small, isolated lakes. Surprisingly, much of this specific information was gleaned from packrat middens, the packrats from a long time ago (think 10,000 years ago) would store things in their cave and then their urine would cement the things together for posterity.

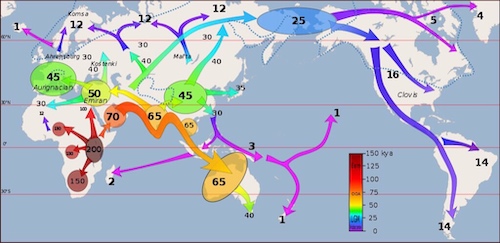

The First Humans Enter the Americas

Even though the Coso People occupied the area where Little Petroglyph canyon is now found, it is unlikely by their own admission, that they created them. We need to go further back in time. Traditional theories suggest that big-animal hunters and animals crossed the Bering Strait from North Asia into the Americas over a land-and-ice bridge (Beringia). This bridge existed from 45,000–12,000 BCE (47,000–14,000 BP) but access to the Americas was blocked by glaciers until 15,000–13,000 years ago.

Human made stone tools have been found in Bluefish cave, in the Northeast of Beringia dating to 25,00–10,000 years ago. A 2007 analysis of mtDNA found evidence that a human population lived in genetic isolation on the exposed Beringian landmass during the Last Glacial Maximum for approximately 5,000 years. This population is often referred to as the Beringian Standstill population. A number of other studies, relying on more extensive genomic data, have come to the same conclusion.

Old Stone Tools and Paleo Indians

Let me begin by saying I do not like the term “Paleo Indian” but that is the term currently used in the literature and unfortunately I use it in this context or no one will understand what I am saying. First discovered in New Mexico in the 1930s, the Clovis culture is known for its distinct stone tools, primarily fluted projectile points. For decades, Clovis artifacts were the oldest known in the New World, dating to 13,000 years ago. But in recent years, researchers have found more and more evidence that people were living in North and South America before the Clovis. Archaeological work in 2012 in Oregon’s Paisley Caves has found evidence that Western Stemmed projectile points, darts or thrusting spearheads, were present at least 13,200 calendar years ago during or before the Clovis culture in western North America.

Even though the projectile points seen above from the Gault site in Central Texas were just published and not a great deal of critical appraisal of the results are available, I felt obliged to include it here. Initially identified in 2002, excavation at the Gault site was undertaken to explore evidence of early cultures in Central Texas. Research focused on the manufacturing technologies, their relationship to Clovis Projectile Points, and the associated age of the assemblages. The stone tool assemblage recovered from the lowest, earliest deposits (seen above) exhibits a small projectile point technology as well as both a biface and a blade-and-core tradition. The projectile points from the Gault Assemblage exhibit two stem morphologies: stemmed and lanceolate. The ages presented in the paper established the presence of a cultural component, stratified below Clovis, and associated with ages older than ~16,000 years BP. This startling age was obtained with both location in the stratified site and Optically-Stimulated Luminescence. As I will discuss below, this technique gives valid age results with proper calibration, that means that the same aged rock recovered in Wyoming and Texas may give different ages with improperly calibrated Optically-Stimulated Luminescence. I have read the paper and I confess I do not have the experience to conclude whether the proper adjustments were made in testing. Nonetheless, the results are pretty amazing and the authors did correlate the results with stratification data.

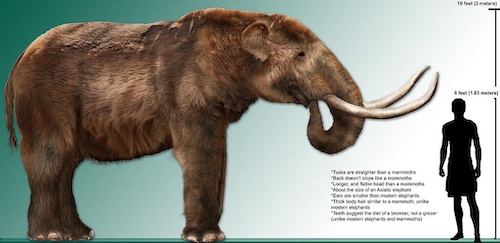

By about 13,250–11,000 BC, discoveries of Paleo Indian and Clovis artifacts in sites with the bones of at least some of these animals leave no doubt that people were here. The best-known Clovis sites in North America are mammoth kills, and this has led many to view Clovis people as specialized big-game hunters. Clovis campsites (best known from Texas) tell a very different story. Clovis people relied on a wide array of large and small animals. They also cached tools on the landscape. By some time after 11,000 BC, most large mammals in North America, including mammoths, mastodons, camels, horses, and many others, were extinct. Bison still ranged into the Rocky Mountains and Paleo-Indians hunted them there, just as plains Paleo-Indians (Folsom People) hunted them (and many other animals) on the open grasslands. The Folsom Complex dates to between 9000 BC and 8000 BC and is thought to have derived from the earlier Clovis culture, hunting mainly buffalo. By 7000 BC and after, people throughout the southwest began to make new styles of spear points and to experiment with new kinds of hunting, marking the end of this period.

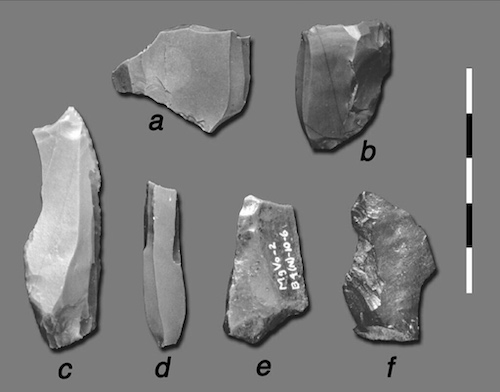

Crescents are enigmatic flaked-stone artifacts found in association with projectile points of Paleoindian age; it has been asserted that they are more frequently found with Great Basin Stemmed points than with Clovis points. They were possibly used as scythes. The crescents seen above all came from areas in or near the Coso mountains.

Later Stone Tools Near the Coso Mountains

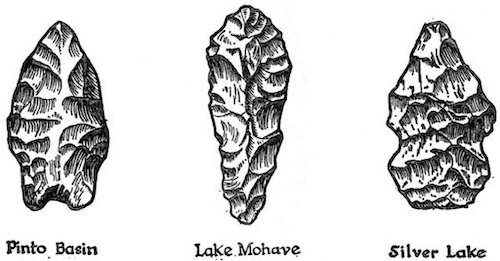

Named for the sites along the shores of pluvial Lake Mohave (Silver and Soda Lake playas) near Baker California, the Lake Mohave Complex was noted by early researchers to contain a range of large stemmed projectile points, flaked stone crescents, steep sided and formalized unifaces and various core cobble tools. What we know of Lake Mohave adaptations is that human populations were low, residential mobility was high and settlement systems involve long-distance shifts in accordance with seasonal resource abundance. They were generalized foragers, exploiting both animal and plant resources in a variety of habitats. One of the resources especially prized at China Lake near the Coso mountains might have been the obsidian. In skilled hands, obsidian can give very sharp points but on the other hand it is brittle and prone to breaking. Hunters in this time frame often resharpened their stone tools so it is interesting to see early obsidian stone tools in this location.

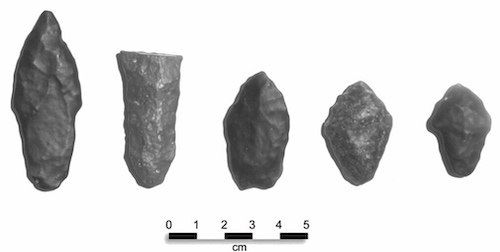

Projectile points found in the Pinto Basin, in Joshua Tree National Forest in the Mohave Desert of Southeastern California, represent the earliest known human occupation of this area. Dated from four to eight thousand years ago, this Pinto culture was first described by amateur archeologists, William and Elizabeth Campbell in the 1930s. The projectile points seen above are from Stahl’s original excavation at Little Lake next to the Coso Mountains. These are classified as Pinto Points by some and Little Lake Points by others. There is variability on both the lower and higher age range due to the fact that Coso Obsidian seems to hydrate faster than obsidian from other sources. This just emphasizes the need for interpretation when viewing the age of an artifact using different techniques.

Native American Language Groups in California

Just to round this post out, since we have gone through all of this information, I thought I would close with the origins of the Native American Language groups west of the Coso/Numic. In Southern California there are two aboriginal language groups: the Hokan and the Uto-Aztecan. One of the descendents of the Hokan language are the Washoe People, the only non-Numic speakers of the Great Basin. Washoe people have lived in the Great Basin and the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains for at least the last 6,000 years. Geographic distribution of the Hokan languages suggests that they became separated around the great central valley of California by the influx of later-arriving Penutian and other peoples. The Miwok of Yosemite and the Central Valley of California are considered to be descendents of Penutian speaking people. At about 3500 years ago, the Uto-Aztecan people moved into the Owens Valley, eventually leading to the Coso, Paiute, Shoshone, Comanche and Ute Native peoples, who occupied the Great Basin and the Colorado plateau.

If you have read this all the way to the end, I hope you will agree that the influence of the tiny Coso/Numic homeland is incredible, reminiscent of the expansion of Rome or Alexander the Great in the ancient world. These were not naked savages, these were spectacularly creative and brave people that lived in an inhospitable world that threatened to kill them daily. This has been a long post with plenty of facts and figures, I would be surprised if you didn’t have questions or comments. I welcome you to respond in the comment box, beneath the post.

References:

Panamint Springs Resort: Travel to Eat

Darwin Falls near Panamint Springs Resort: Travel to Eat

Geology in Southern Owens Valley

Gene Quintana: Panamint Baskets

Eastern Sierra Ancient History

Catherine Louise Sweeney Fowler. 1972. “Comparative Numic Ethnobiology”. University of Pittsburgh PhD dissertation.

Comparative Numic Ethnobiology

Ahwahnechee or Awahnichi (″Yosemite Valley People″) a Miwok People

Indian Grinding Rock State Historical Park

Yosemite Indians, Tools and Trade

Coso Petroglyphs and Mythology

Pollen Counts During the End of the Last Ice Age in Owens Valley

Archeology Periods in North America

Population Dispersal in Western North America

Bluefish Caves and Old Crow Basin Stone Artifacts

Pre-Clovis Points in Paisley Caves, Oregon

Paleo Indian Points Timeline. David Anderson et al

Clovis Points at Twentynine Palms, California

Coso Junction Point Collection, Maturango Museum

Natve American Stone Points Types

Little Lake Pinto Points. Clement Meighan

China Lake, Mojave Complex Projectile Points. Giambastiani and Bullard