When I first moved to Las Vegas there were virtually no mosquitoes and no flies. However as the population has increased and the local climate has changed with more landscaping and water we have seen a corresponding increase in bugs. That is not to say that there were no insects in the desert, as with flowers and plants you just have to look more carefully. There are an amazing variety of specialized insects living in the desert surrounding Las Vegas under conditions that would be considered hostile for any other insects. Again just like flowers and plants, the insects can come and go quickly over specific times like spring or after precipitation and are often found in specific areas suited to their needs. The Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve is a great place to see lots of unusual insects due to the presence of water and hospitable plants. Bees, wasps, dragonflies and butterflies are diverse and are part of the special ecology of the preserve, both prey and predator for birds and other inhabitants. Fortunately, there are very few mosquitoes, probably due to the dragonflies and the dry heat. Due to carefully selected and strategic native plants, there are a variety of native flowers all summer long which support a diverse and vibrant ecosystem. In this post I thought I would focus on some really interesting bees and wasps which I saw at the preserve.

Tarantula Hawk

Tarantula Hawks are large, interesting wasps that live in the Mojave Desert. They probably eat lots of things, but one thing females do is sting and paralyze Tarantulas. They then lay an egg on the tarantula, bury it, and let the developing larva eat the live tarantula until it is ready to pupate and hatch into a young adult. Tarantula Hawks can grow up to 2 inches (5 cm) in length. The wasp is about 1/3 of the size of a tarantula, but they are effective predators. There are 250–300 species of tarantula hawks worldwide. Over 250 species can be found in South America whereas 15 species occur in the United States (9 of them inhabit deserts). There are 15 species of Tarantula Hawks in North America, but in Nevada, only one is common: Pepsis thisbe. This species is recognized by the large size (of females), the blue-black body with orange wings, and black antennae. Another fairly common species, Pepsis grossa, has red on the antennae, but is more common in Arizona. Pepsis thisbe can grow up to 2 inches (5 mm) in length. Tarantula hawks have dark blue, iridescent bodies, bright orange wings, and long legs. Male and female Tarantula Hawks vary in subtle ways. Male antennae are straight and their abdomens are segmented into 7 sections. Female antennae are curved and their abdomens have only 6 segments.

While adult tarantula hawks are nectavores and feed on flowers, they get their name because adult females hunt tarantulas as food for their larvae. The wasp is about 1/3 of the size of a tarantula, but they are effective predators. An adult female will paralyze a tarantula with its stinger, and then transport the spider back to the hawk’s underground nest. Once there, the female lays an egg in the spider’s abdomen, then covers the entrance of the burrow to trap the spider. Once the egg hatches, the larvae will feed on the still living spider for several weeks, avoiding vital organs to keep the spider alive until the larvae pupates into an adult wasp. Males do not have stingers, but females have a ¼ inch (7 mm) stinger. They will not sting unless provoked, but their sting is reported to be the second most painful sting of any insect. Roadrunners are one of the few animals that will risk being stung to feed on tarantula hawks.

Pacific Cicada Killer

The Pacific Cicada Killer (Sphecius convallis) is only one of four species that occur in the United States, all named for their prey. Solitary females sting adult cicadas and drag them back to their individual underground burrows as food for their larval offspring. There are also the Eastern Cicada Killer, (Sphecius speciosus), Western Cicada Killer (Sphecius grands) and the Caribbean Cicada Killer (Sphecius hogardii), which ranges into southern Florida. The Pacific Cicada Killer can be up to 1.5 inches long (3.8 mm), males are a little smaller than the females. Cicada-killer wasps such as the Pacific cicada killer (Sphecius convallis) face the threat of kleptoparasitism, the theft of their prey by other animals. Birds are common thieves, though a captured cicada left unguarded in an underground nest can also be commandeered by other cicada killers—particularly in times of high competition for prey. Female cicada killers have the spines on the hind tibia modified into heavy, blade-like appendages, clearly visible in the images above. They use these blades to help kick soil out of the burrow as they dig with the front legs. The female wasps are generally larger and bulkier than the males as well, but are too busy nesting and hunting to bother attacking people or any other animal. One author who has been stung indicates that, for him, the stings are not much more than a “pinprick”. Males aggressively defend their perching areas on nesting sites against rival males but they have no stinger. Although they appear to attack anything that moves near their territories, male cicada killers are actually investigating anything that might be a female cicada killer ready to mate.

Pacific Cicada Killers are known to use Apache Cicadas, Diceroprocta apache, and Silver-bellied annual cicadas, Tibicen pruinosus as hosts. Apache Cicadas are native to the Southwestern United States, and the Las Vegas Valley. The noise they make is caused by two membranes that the male Cicada has on his abdomen. They are located just behind his wings, and a vibration he makes causes that noise. His entire body is made in a way that amplifies the noise, which is why it does sound so loud to us. Apparently, female Cicadas like this. Five to ten days after mating, the female lands on twigs of deciduous trees, cuts slits in them, and lays her eggs in the slit. Shortly after mating, the male Cicada dies. The eggs hatch, producing tiny nymphs that fall to the ground. These nymphs burrow into the soil and feast on underground roots. They remain there for years, slowly growing, until their periodic cycle calls them to emerge again as adults. As larvae and nymphs they suck tree fluids from the roots of deciduous trees (trees that lose their leaves in the fall). This type of cicada spend the bulk of their lives living in underground burrows, emerging in overlapping three to five year cycles in May to late June as nymphs. We pretty much have them every year. The nymphs climb up walls or trees and emerge as adults, leaving the cask skins of the nymphs clinging to the base of the walls or tree trunks. Adults do not eat.

Periodical cicadas, unlike annual cicadas or Apache Cicadas, emerge every 13 or 17 years, depending on the species. In parts of southwestern Virginia, North Carolina and West Virginia, it’s nearly time for a brood of the insects to emerge for their once-in–17-year mating season. As many as 1.5 million cicadas could emerge per acre in 2020.

Golden Paper Wasp

The Golden Paper Wasp (Polistes aurifer) occurs in the western part of North America, from southern Canada through the United States to northern Mexico. The species has different color patterns depending on geography. Northern specimens are often mostly black, with ample yellow markings but with the ferruginous (rusty red) color being very restricted. In populations from the southwestern USA forms with almost completely yellow abdomens are more common. Although paper wasps and other social wasps have the reputation for being aggressive, this species (and perhaps the entire genus, ~19 species) and the related Mischocyttarus is relatively gentle and nonaggressive. This is a moderately large wasp, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in length with a forewing length of 0.4–0.7 inches (11.5–17.0 mm).

Mexican Honey Wasp

The Mexican Honey Wasp (Brachygastra mellifica) is a neotropical social wasp. It can be found in both North and South America. They can be found from southern United States to Northern Argentina and include a total of 16 species. Brachygastra mellifica is the only species present in the US, found in both Arizona and Texas and ranges from Texas to Nicaragua. They are smaller than European Honey Bees, only 0.3–0.35 inches (7–9 mm) in length. It is one of few wasp species that produces honey. This wasp species is of use to humans because they can be used to control pest species and pollinate avocados. This genus is known for its easily recognizable abdomen, which can be almost as wide as it is long. Brachygastra mellifica is very similar in morphology to Brachygastra lecheguana but differs in its geographic distribution (Central and South America). They build large paper nests up to a foot in diameter with up to 50,000 members.

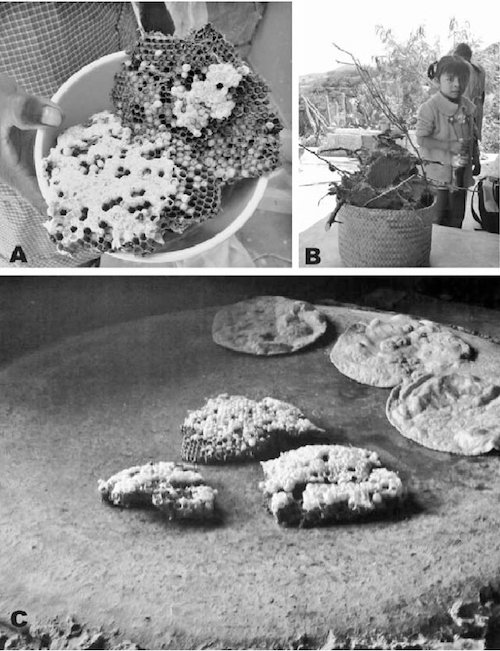

Brachygastra mellifica serve as food source for the Popoluca Town of Los Reyes Metzontla, Mexico. The Popolucas have at least 17 species of insects in their diet, including Brachygastra mellifica. The Spanish local name for this delicacy is “Panal Miniagua”, and the Popoluca name is “Cuchii”. They eat the honey and larva of these wasps year round, but only harvest when the moon is between its last quarter and waning.

Paper Wasp Nest

I saw this paper wasp nest in Costa Rica and decided to include it. Polybia occidentalis, commonly known as camoati, is a swarm-founding advanced eusocial paper wasp. Swarm-founding means that a swarm of these wasps find a nesting site and build the nest together. This species can be found in Central and South America, from Mexico to northern Argentina. This species of wasp is common in Costa Rica and Brazil. Polybia occidentalis preys on nectar, insects, and carbohydrate sources, while birds and ants prey on and parasitize them. The workers bite each other to communicate the time to start working, sounds like a bad place to work. This nest is interesting because of the “drip tips or fingers” used to channel rain off the paper nest. It is built on the underside of the leaf for the same reason.

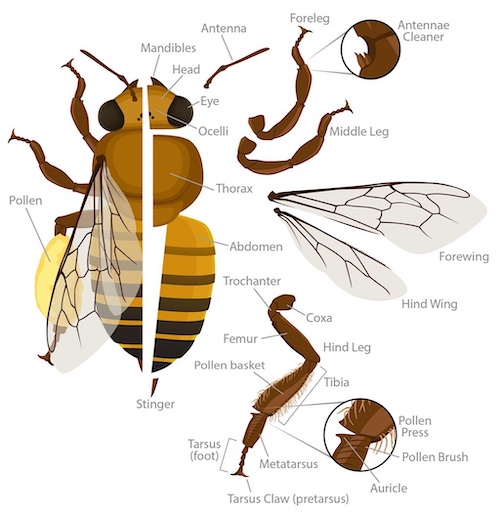

Bee Anatomy

Scientists suspect that bees and flowering plants both evolved around 100 million years ago, in the middle of the Cretaceous period. Before this period, many plants reproduced the way today’s conifers do. They released seeds and pollen using cones. The wind carried the cones, and eventually the pollen came into contact with the seeds and fertilized them. Unlike conifers, flowering plants, called angiosperms, needed the help of insects and other animals to reproduce. Insects had to physically move pollen grains from plants’ anthers, or their male structures, to their stigmas, or female structures. A bee’s body has a lot in common with the bodies of other insects. Much of it is covered in an exoskeleton made from small, movable plates of chitin. A bee’s body is also covered in lots of fuzzy, branched hair, which collects pollen and helps regulate body temperature. The body also has three sections — the head, the thorax and the abdomen. The honey bees exoskeleton is covered with layers of wax. The main component of exoskeleton is chitin which is a polymer of glucose and can support a lot of weight with very little material. The wax layers protect bees from desiccation (losing water). Bees breathe through a complex network of tracheas and air sacs. Oxygen is vacuumed into the body through openings on each segment (spiracles) by the expansion of the air sacs, then the spiracles are closed and air sacs are compressed to force the air into smaller tracheas, which become smaller and smaller until individual tubules reach individual cells.

Honey Bees

I am by no means an entomologist (bug expert), I came to photograph bees almost by accident. I found that photography of flowers was much enhanced by including the insects that were always flying around. Over time, I have become more interested in the insects themselves and find both similarities and differences to my usual bird photography. Both use specialized lenses (telephoto vs macro), both require patience and lighting/isolation is important to both. One interesting fact about pollinators is that they tend to be more prevalent in bright sunlight. This is good for macro photography but requires that you find the right kind of flowering plant in full sunlight or wait until the location you have selected in the shade becomes covered in light. Not all flowering plants will attract insects at all times. For whatever reason, there seems to be a “flavor of the day” that attracts the most interest so you will need to check them all. Finally, just as in bird photography, flash is always better and results in less noise and more detail, even in direct sunlight. I set my flash and camera on manual rather than TTL and I use an Olympus 60mm macro lens which allows for some distance from the subject. Finally, you will need to try to ignore the many honeybees quickly enough to find the “odd man out” that you want to photograph. I hope these tips will help you and I plan to do more insect posts in the future.

Sweat Bees

Sweat Bees (Halictidae) is the second-largest family of bees. Halictid species occur all over the world and are usually dark-colored and often metallic in appearance. Several species are all or partly green and a few are red; a number of them have yellow markings, especially the males, which commonly have yellow faces, a pattern widespread among the various families of bees. They are commonly referred to as “sweat bees” (especially the smaller species), as they are often attracted to perspiration. They are only likely to sting if disturbed; the sting is minor.

Augochloropsis is a genus of brilliant metallic, often blue-green, sweat bees in the family Halictidae. There are at least 140 described species in Augochloropsis. Species of the genus Augochloropsis are generally between 0.3–0.5 inches (8–12 mm) long and metallic, typically bright green or blue in color, with some exceptions such as gold, red, or purple. Although the vast majority of species are found in the tropical and subtropical regions, three Augochloropsis species are found in the temperate regions of North America.

Halictus ligatus is a species of sweat bee from the family Halictidae, among the species that mine or burrow into the ground to create their nests. They are small, about 0.3–0.4 inches (7–11 mm) in length. The nests of Halictus ligatus occur either in rotting wood or within the ground. Halictus ligatus is one of the most abundant and readily identifiable bees in North America, encompassing a wide range of aridities and altitudes. The species can be found in North American for about 50 degrees north latitude, south to the West Indies and Colombia. H. ligatus is also located in temperate areas of the Atlantic to the Pacific, including the southern Gulf of Mexico and southern Canada.

Cuckoo Bees

With over 850 species, the genus Nomada is one of the largest genera in the family Apidae, and the largest genus of kleptoparasitic “cuckoo bees.” Kleptoparasitic bees are so named because they enter the nests of a host and lay eggs there, stealing resources that the host has already collected. The name “Nomada” is derived from the Greek word nomas (νομάς), meaning “roaming” or “wandering.” They are often extraordinarily wasp-like in appearance, with red, black, and yellow colors prevailing, and with smoky (infuscated) wings or wing tips. They vary greatly in appearance between species, and can be stripeless, or have yellow or white integumental markings on their abdomen. As parasites, they lack a pollen-carrying scopa, and are mostly hairless, as they do not collect pollen to feed their offspring. Like non-parasitic bees, adults are known to visit flowers and feed on nectar. Nomada suavis Is about 0.25 inches (12 mm) in length.

Carpenter Bees

California Carpenter Bees (Xylocopa californica) are large, one inch (2.5 cm) long, bumblebee-like bees that are not covered with dense hairs. Female carpenter bees chew into wood forming galleries where they store food and lay eggs. Males often patrol outside the burrows driving away other males and hoping for a chance to mate. One of the more commonly spotted flying insects, California carpenter bees (Xylocopa californica) buzz through the air looking for nectar in flowers. These large, shiny, black-blue insects may look menacing but they’re very docile animals that will only sting when agitated. California carpenter bees get their name by boring holes into tree stumps, fence posts, and other wood structures. These bees lay their eggs in the holes and also use holes as homes for shelter through the winter season. Look for California Carpenter Bees near Las Vegas on top of Mojave Thistle (Cirsium mohavense), Desert Thistle (Cirsium neomexicanum) and of course Desert Willow (Chilopsis linearis), to which they seem to have a special affinity.

Hoverflies

Hoverflies, also called flower flies or syrphid flies, make up the insect family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed mainly on nectar and pollen, while the larvae (maggots) eat a wide range of foods. In some species, the larvae are saprotrophs, eating decaying plant and animal matter in the soil or in ponds and streams. In other species, the larvae are insectivores and prey on aphids, thrips, and other plant-sucking insects. Many species are brightly colored, with spots, stripes, and bands of yellow or brown covering their bodies. Due to this coloring, they are often mistaken for wasps or bees; they exhibit Batesian mimicry (pretending to be a wasp to fend off predators). Despite this, hoverflies are harmless to humans. Palpada agrorum are about 0.27 inches (7 mm) in length.

Bees in History

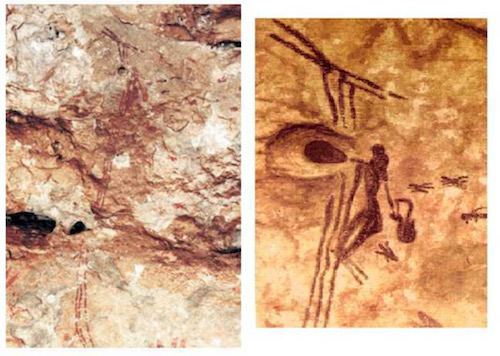

This painting is frequently referred by historians and anthropologists as the first recorded evidence of the ancient history of bee keeping, and was discovered in 1924 by a local teacher, Jaime Garí i Poch. In this painting in the ‘Cave of the Spider’ (Cueva de la Araña), Bicorp, Valencia, dating back as many as 7,000 to 15,000 years, is a cave painting that depicts a man working with honeybees.

Ancient Beehives in Israel

Hives uncovered during a dig at the ancient city of Rehov in northern Israel may provide the oldest evidence of honeybee husbandry in the Near East. Dated around 900 BC by archaeologist Amihai Mazar of Hebrew University, the hives could be the oldest found, anywhere. Each of the cylindrical hives measured 2–1/2 feet long and one foot in diameter, and were constructed of unbaked clay and straw. Each hive had a removable plug at one end, through which the beekeeper could extract the honeycomb, and a small hole for the bees on the other. Stacked in rows three high, the 30 hives discovered could have produced up to one half ton of honey per year, according to the archaeologist’s estimate. And the area in which these hives were discovered may have accommodated another 70 hives.

Date Honey

This find should put an end to claims by some that ancient Palestine was not conducive to bee keeping:

“Biblical scholars believe that the honey repeatedly mentioned in the Torah likely came from dates and other fruits, not bees.” Ancient Palestine was not conducive to bee hives or beekeeping, this interpretation holds, so we should actually think of something like date paste when we come across biblical statements such as Jacob’s instructions to his sons as they were returning to buy food from Joseph in Egypt: “Put some of the best products of the land in your bags and take them down to the man as a gift—a little balm and a little honey, some spices and myrrh, some pistachio nuts and almonds.” In fact, while Silan or date paste/honey is a delicious and durable product of antiquity, particularly from Persia, there is ample evidence both in the Bible and in this archaeology find that real honey from bees was made and used in ancient Israel.

Gold Bee Jewelry from Minos

The Palace of Malia, is the third largest of the Minoan Palaces, covering an area of around 7,500 square meters and, according to myth was ruled by Sarpedon, son of Zeus and Europa and brother of the famous King Minos. The Palace was originally constructed in 1900 BCE but was destroyed by an earthquake 1700 BCE. These pendants were found in the a tholi nearby, a structure shaped like a beehive, used for burials. Both Minoans and Mycenaeans buried their dead in circular structures, known as tholoi. Minoans built their tholoi above ground, with small doors and round tomb chambers. Archaeological excavations confirmed that Minoans buried all members of their settlements in these tombs. The communal status of Minoan tholoi explains the simplicity in the architectural style and the lack of decorations. The Malia Honeybees Pendant is made from gold and comprises two bees, their bodies curved towards each other and their wings outstretched, clasping a honeycomb into which they are placing a small drop of honey. The piece is striking not only because of its unusual composition and intricate rendering, but also because of the significance of its subject-matter. In the cultures of the Ancient Near East and Aegean, the bee was believed to be a sacred insect, especially associated with connecting the natural world to the underworld, which helps to explain why a pendant with such a design was placed in the tomb with the deceased. Often, the bee appears in tomb decoration and, in Mycenae, so-called tholos tombs were sometimes even shaped as beehives. It is believed that the Great Mother of Mother Goddess was related to bees, while honey was used in rituals. As a symbol of the Mother Goddess, bees represent the mutual support and fertility. Later on, Greek Goddess priestesses were called melissae (bees) and bees were associated with Demeter and Artemis.

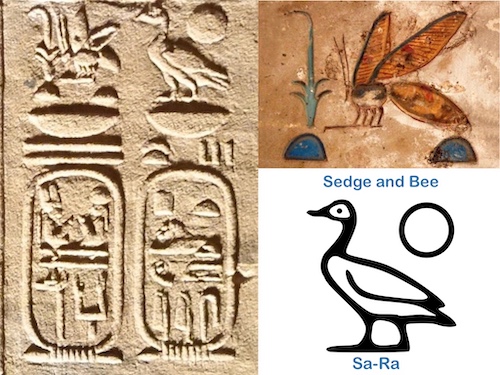

Bees in Ancient Egypt

It cannot be disputed that the Ancient Egyptians attached great religious and spiritual significance to the honey bee. Bees were associated with royalty in Egypt. The pharaoh’s throne name (prenomen) was the first of the two names written inside a cartouche and is usually labled, above the cartouche as seen above, with the title “nsw-bity”. This ancient term literally means “He of the Sedge and Bee”, but is often translated for convenience as “King of Upper and of Lower Egypt”. The bee is the symbol for Lower Egypt and sedge is the symbol for Northern Egypt.

For at least four thousand five hundred years, the Egyptians have been making hives in the same way, out of pipes of clay or Nile mud, often stacked one on top of another. These hives were moved up and down the Nile depending on the time of year, allowing the bees to pollinate any and all flowers which were in season. Special rafts were built for moving these hives, which were stacked in pyramids. At each new location, the hives were carried to the nearby flowers and released. When the flowers died, the bees were taken a few miles further down the Nile and released again. Thus the bees traveled the whole length of Egypt. This tradition continues into the present day.

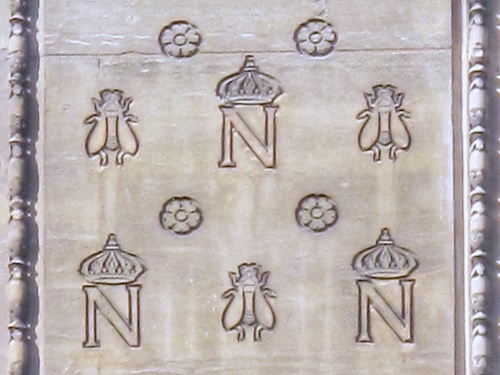

Napoleonic Bees

Although he was never a beekeeper, Napoleon used the honey bee as one of the most important symbols of the power and prestige of his empire. There seem to be two schools of thought of why Napoleon chose the honey bee as part of his iconography. One school of thought says the honey bee is representational of the Merovingian kings (Childeric I), the founders of France, with whom Napoleon sought to align himself. My own thought is that Napoleon was quite taken with ancient Egypt, after invading he launched a number of studies, both artistic and scientific. Napoleon brought along 150 savants — scientists, engineers and scholars whose responsibility was to capture, not Egyptian soil, but Egyptian culture and history. After their return to France in 1801, they continued to organize materials, and finally, in 1809, the first volumes of the “Description de l’Égypte” were published. Over the years, concluding in 1828, a total of 23 volumes would appear. Three of these were the largest books that had ever been printed, standing over 43 inches tall. The total set contained 837 engravings, many of them of unprecedented size, which captured Egyptian culture from every possible vantage point. Europeans of the time looked to ancient Egyptian motifs because ancient Egypt itself was intrinsically so alluring. The Egyptians considered their religion/government eternal, they were supported in this thought by the enduring aspect of great public monuments which appeared to resist the effects of time. The Napoleonic bees were a natural choice for a symbol of his tenure, reminding the populous of his achievements and the durability of his reign. In any case, those little bees can be found in many of the buildings and paintings of the Napoleonic era.

As always I hope you enjoyed the post and will return for more in the future.

References

Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve

Trinidad and Tobago Bees, Butterflies and Bugs

Tarantula Hawk. BirdandHike.com

They’re Back: Millions Of Cicadas Expected To Emerge This Year. NPR

Bee Anatomy. Arizona State University

Nevada Bees. Insect Identification

Carpenter Bees In Red Rock Canyon

Friends of the Earth Bee Identification

Insects that look like bees. Michigan State

Murder Hornets, Bees, Wasps and Hoverflies: Learn the Difference Between Striped Insects

Ptolomy II in the Temple of Isis from Philae. TraveltoEat

Childeric I Bees and Napoleon I

Cueva de la Araña, Valencia Spain

Bee Keeping in Ancient Egypt. Egypt Museum

Oldest Bee Hives Discovered in Israel