Almost every place that we visit near the sea, I look for a maritime museum. In Sydney, we visited the Australian National Maritime Museum and I was not disappointed. This museum has real ships, exhibits on a multitude of subjects and beautiful nautical models, paintings and instruments. In June 1985, the Australian government announced the establishment of a national museum focusing on Australia’s maritime history and the nation’s ongoing involvement and dependence on the sea. Proposals for the creation of such a museum had been under consideration over the preceding years. After consideration of the idea to establish a maritime museum, the Federal government announced that a national maritime museum would be constructed at Darling Harbour, tied into the New South Wales State government’s redevelopment of the area for the Australian bicentenary.

As you walk into the museum, they have an exhibit of items recovered from the wreck of HMS Sirius. HMS Sirius was the flagship of the First Fleet, which set out from Portsmouth, England, in 1787 to establish the first European colony in New South Wales, Australia. Sirius was wrecked off the coast of Norfolk Island in the Pacific Ocean in 1790. They had various items such as the anchor and blackened copper nails and bolts on display. The general location of the wreck was recorded by contemporary witnesses in both documentary accounts and drawings: however it was only after an initial survey of the underwater site by divers from the Western Australian Maritime Museum in 1983 that the archaeological potential of the wreck was confirmed. Focus on the wreck heightened during preparations for Australia’s bicentennial celebrations in 1988 and there were expeditions to the Sirius wreck site in 1985, 1987, 1988 and 1990.

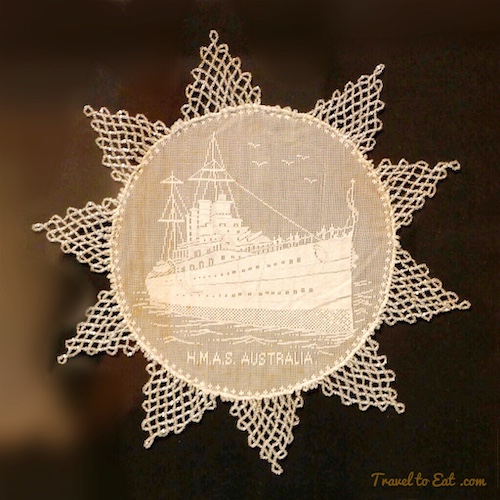

During the opening weeks of the First World War, the SMS Emdon waged an astonishing pirate campaign through the South Pacific and Indian Ocean. The short-lived expedition left more than 30 Allied ships ablaze, ground British trade in the Far East to a standstill and terrorized the ports and sea lanes of more than a quarter of the Earth’s surface. On November 9, 1914 the Emden was sunk by the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney in the “Battle of Cocos” after the Emdon attacked a communications station at Direction Island. This shield is a trophy from that battle.

This figurehead of British Vice Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson comes from “HMS NELSON”, later commissioned “HMVS NELSON” (Her Majesty’s Victorian Ship). The battleship was launched on 4 July 1814 in England but came to be a familiar sight on Victoria’s Port Phillip Bay.

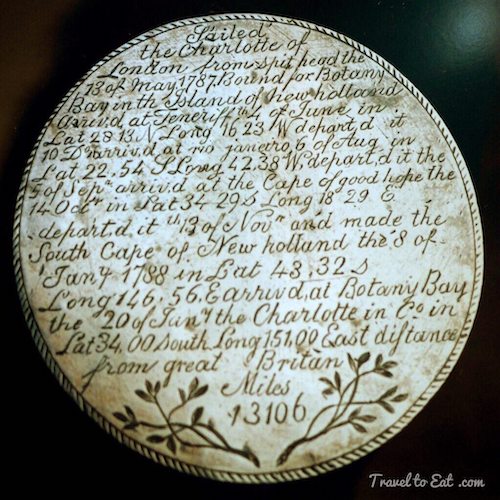

The Charlotte Medal is a silver medallion 74 millimeters (2.9 in) wide, depicting the voyage of the Charlotte, with the First Fleet, to Botany Bay, Australia. Its obverse depicts a scene of the ship and its reverse is inscribed with a description of the journey. The medal is said to be the first work of Australian colonial art. During the journey the Charlotte visited Rio de Janeiro. While at anchor, one of the ship’s convicts, a forger and mutineer by the name of Thomas Barrett was caught giving locals fake coins made from buckles, buttons and spoons. The Surgeon-General of the Fleet, John White was impressed with his skill in making these forgeries, without having the apparent means to do so. This led him to commission Barrett to make the medal, to commemorate the journey, possibly from the surgeon’s silver kidney dish. In 2008 the Australian National Maritime Museum, with funds from the National Cultural Heritage Account, authorized through the Australian Government, won an auction for the medal with a bid of $750,000.

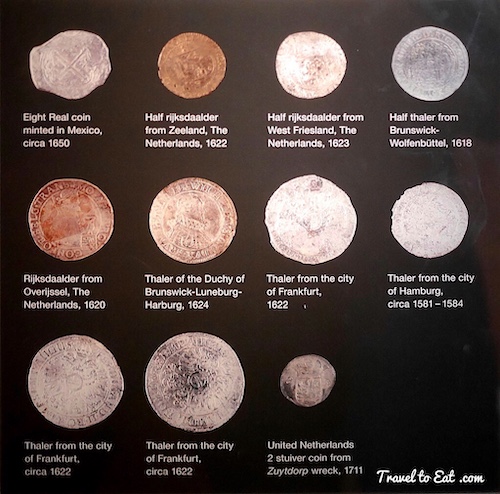

When “VOC Batavia” (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, commonly abbreviated VOC) was wrecked in 1629 it was loaded with coinage to purchase spices in the Dutch East Indies. Commander Pelsaert salvaged eight of the ten chests of silver coins. The other two were recovered by divers in the 1960’s and contained around 9,000 coins. Most of the Batavia coins were rijksdaalders from the Netherlands along with German thalers (the origin of the word dollar). The oldest coin in the find dates from 1542. Despite being on thc sea floor for hundreds of years a number of the coins have survived remarkably intact, still showing their striking design elements. The Spanish coins valued at eight reales were minted in Mexico in the mid-17th century. They come from the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck, another Dutch ship wrecked off the West Australian coast, in 1656. They were known as Spanish Dollars, or pieces of eight.

These coins are one of several hundred objects recovered from the wreck of the VOC Zuytdorp, a Dutch East India Corporation vessel wrecked off the Western Australia coast in 1712. The VOC Zuytdorp also Zuiddorp (meaning ‘South Village’ after a still existing village in the South of Zeeland, near the Belgian border) was an 18th-century trading ship of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, commonly abbreviated VOC). An infamous predecessor of the Zuytdorp, the VOC Batavia was wrecked on the Houtman Abrolhos islands not far south from the later wreck of the Zuytdorp. In 1964 a team led by Geraldton identity Tom Brady, including Graham and Max Cramer, conducted the first dive on the wreck, and on a subsequent dive later found a veritable “carpet of silver”.

P&O (merged with Carnival) first introduced passenger cruising services in 1844, advertising sea tours to destinations such as Gibraltar, Malta and Athens, sailing from Southampton. The forerunner of modern cruise holidays, these voyages were the first of their kind, and P&O Cruises has been recognised as the world’s oldest cruise line. RMS Orcades was a British passenger ship that Vickers-Armstrongs Ltd of Barrow-in-Furness built as an ocean liner in 1937. Her owner was Orient Line, which operated her between Britain and Australia 1937–39, and also as a cruise ship. The Admiralty then requisitioned her and had her converted into a troopship. Cruising was was not quite as luxurious as it is today, without an onboard doctor, and passengers were encouraged to take their own medicines while the ship would have a large medical chest to supplement. The pictures above show the ship medical chest from the Samuel Plimsoll (1873-1903) and a private box from 1880. God forbid you should require a surgeon as you can see from the saws and pliers in Surgeon Cloverdale’s kit from 1837.

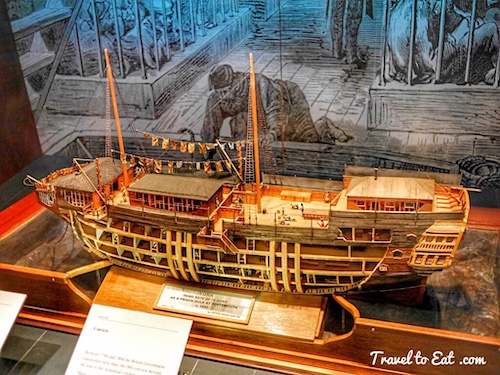

Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 162,000 convicts were transported to the various Australian penal colonies by the British government. Many prisoners were confined in crowded person hulks before being transported. York was a 74-gun Third-rate launched in 1807 at Rotherhithe. She was converted to a prison hulk in 1819 and served as a prison hulk at Gosport and London from 1820 until 1848 when a serious rebellion broke out. Typically she confined about 500 convicts. She was taken out of service and broken up in 1854. This model represents the British prison hulk YORK on a scale of 1: 64. It was inspired by an engraving by the artist Edward William Cooke of the YORK in Portsmouth harbour. The model is cut away to reveal figures of convicts, guards and soldiers undertaking their daily duties. Over 500 prisoners were held on board YORK at the one time, in unsanitary and cramped conditions. This environment resulted in disease and malnutrition in the prisoners and a rebellion in 1848.

This late 18th century pantograph, by instrument maker Benjamin Martin, was used for copying charts and maps at various scales. Parts of a pantograph similar to this one have been recovered from the wreck site of HMS SIRIUS – wrecked at Norfolk Island in March 1790. Around 1770 Benjamin Martin published a pamphlet advertising his new improved pantograph, an example of which is here. This is pretty much the perfected design for the instrument, it remined relatively unchanged until its demise in the 20th century; later makers copied this design very closely.

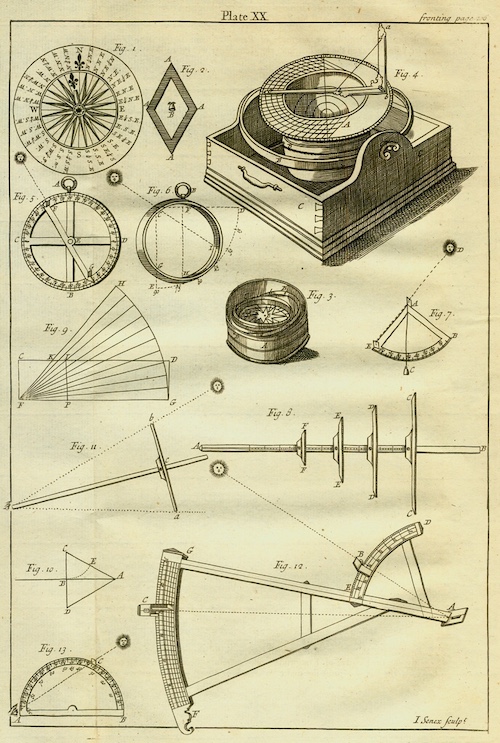

Early instruments for navigation. Plate XX from N. Bion’s The Construction and Principal Uses of Mathematical Instruments. Translated from the French of M. Bion. To Which Are Added The Construction and Uses of Such Instruments as Are Omitted by M. Bion; Particularly of Those Invented or Improved by the English. By Edmund Stone. . . . (London, 1723). [Rare Books Division]

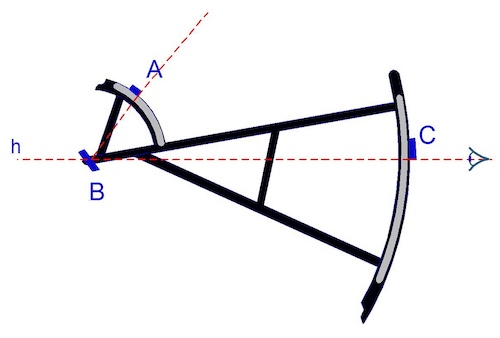

As anyone who reads this blog knows, I am very fond of maritime instruments. They have some very old and well made instruments at the Australian National Maritime Museum, although not all of them are on display. I am not going to explain the use of these instruments except in broad terms, please refer to my previous posts referenced below for more information. I have never seen an original 18th century Davis Quadrant or Backstaff before (named because it could measure up to 90 degrees). Captain John Davis invented a version of the backstaff in 1594. Davis was a navigator who was quite familiar with the instruments of the day such as the mariner’s astrolabe, the quadrant and the cross-staff. Both arcs have a common center, the upper 60 degrees and lower 30 degrees. At the common center, a slotted horizon vane is mounted (B). A moveable shadow vane is placed on the upper arc so that its shadow is cast on the horizon vane. A moveable sight vane is mounted on the lower arc (C). The user lined up the sun shadow and the horizon to get the elevation of the sun. The Davis Backstaff had the advantage of not looking directly at the sun as you had to do with the Jacob Staff or Cross Staff. The Backstaff was replaced in the 1700s by the quadrant, then the octant and finally by the modern sextant.

Two men independently developed the octant around 1730: John Hadley (1682–1744), an English mathematician, and Thomas Godfrey (1704–1749), a glazier in Philadelphia. While both have a legitimate and equal claim to the invention, Hadley generally gets the greater share of the credit. The octant seen above must have been one of the very first Hadley models. Hadley placed an index mirror on the index arm which could move 45 degrees. Two horizon mirrors were provided. The upper mirror, in the line of the sighting telescope, was small enough to allow the telescope to see directly ahead as well as seeing the reflected view. The reflected view was that of the light from the index mirror. The arrangement of the mirrors allowed the observer to simultaneously see an object straight ahead and to see one reflected in the index mirror to the horizon mirror and then into the telescope. Moving the index arm allowed the navigator to see any object within 90° of the direct view. The second horizon mirror was an interesting innovation. The pinhole could be rotated to view the second horizon mirror from the opposite side of the frame. By mounting the two horizon mirrors at right angles to each other and permitting the movement of the telescope, the navigator could measure angles from 0 to 90° with one horizon mirror and from 90° to 180° with the other.

Early octants retained some of the features common to backstaves, such as transversals on the scale. However, as engraved, they showed the instrument to have an apparent accuracy of only two minutes of arc while the backstaff appeared to be accurate to one minute. The use of the vernier scale allowed the scale to be read to one minute, so improved the marketability of the instrument. In addition, using ivory or brass for the vernier scale further improved accuracy and legibility. This and the ease in making verniers compared to transversals, lead to adoption of the vernier on octants produced later in the 18th century.

This photograph shows details of the working parts of the Octant including the double-holed sighting pinnula which was used at the time since the poor optical quality of the early polished speculum metal mirrors meant that telescopic sights were not practical. For that reason, most early octants employed a simple naked-eye sighting pinnula instead. The index mirror is attached to the movable arm and reflects the image of the sun, through filters to the half height horizon mirror. Thus the observer can observe both the sun and the horizon through the hole in the pinnula, one on top of the other. Using shades over the light paths, one could observe the sun directly, while moving the shades out of the light path allowed the navigator to observe faint stars. This made the instrument usable both night and day.

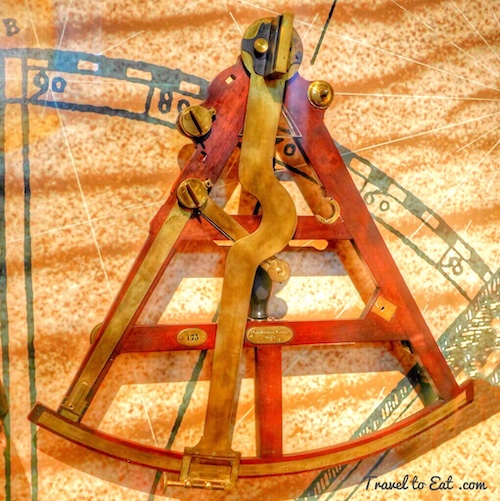

They had this beautiful wooden, brass and ivory octant on display from the firm of Spencer, Browning and Rust. Ebenezer Rust, son of Joseph Rust, was an apprentice to Richard Rust (died 1785), and most probably his nephew. Richard Rust was a renowned mathematical instrument maker in Ratcliff and Wapping, London, and the first of a line of English instrument makers. Richard Rust was master to a number of apprentices, including William Spencer, Samuel Browning, and Ebenezer Rust. The seven-year contract of indenture of Ebenezer Rust to Richard Rust was dated 6 March 1770. On 5 April 1770, Richard Rust, “Citizen and Grocer of London” paid a fee for the indenture of Ebenezer Rust, who was then freed from his apprenticeship in 1777, and joined the partnership of Spencer and Browning in 1784. Spencer, Browning and Rust, a manufacturer of scientific instruments in England from 1787 to 1840 (operating as Spencer, Browning and Co. after 1840) used a Ramsden dividing engine to produce graduated scales in ivory. These were widely used by others and the SBR initials could be found on octants from many other manufacturers.

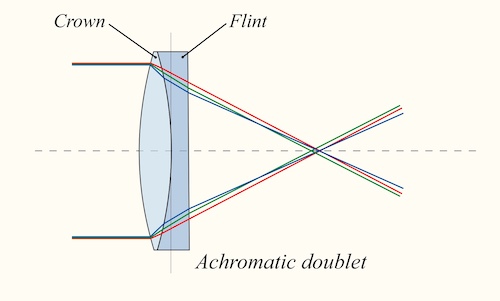

In 1767 the first edition of the Nautical Almanac tabulated lunar distances, enabling navigators to find the current time from the angle between the sun and the moon. This angle is sometimes larger than 90°, and thus not possible to measure with an octant (without the second mirror). For that reason, Admiral John Campbell, who conducted shipboard experiments with the lunar distance method, suggested a larger instrument and the sextant (with a 60 degree frame) was developed. Peter Dolland (1731-1820) was the son of John Dolland (1706-1761) who was the first person to patent the achromatic doublet. However, it is well known that he was not the first to make achromatic lenses. Optician George Bass, following the instructions of Chester Moore Hall, made and sold such lenses as early as 1733. In the late 1750s, Bass told Dollond about Hall’s design; Dollond saw the potential and was able to reproduce them. His son Peter enforced the patent and primarily made telescopes and microscopes. Dollond telescopes, for sidereal or terrestrial use, were among the most popular in both Great Britain and abroad for a period of over one and half centuries. Admiral Lord Nelson himself owned one. Another had sailed with Captain Cook in 1769 to observe the Transit of Venus. He developed this Sextant with very well made glass mirrors but a funky method of adjusting the back mirror which never caught on.

This sextant was not on display but I wanted to show the form of an early 19th century sextant. This copper alloy double framed sextant is attributed to Troughton and Simms of London, England. Sextants were used to obtain the angles or height from the horizon of a celestial body such as stars, planets, the moon or the sun. This information could then be used to calculate a vessels latitude and, aided by a chronometer and mathematical tables, its longitude. The construction technique used for this sextant produced a very rigid robust and accurate instrument and was first developed by Troughton and Simms in the early 1800s and remained popular until the development of lighter sextants in the 1850s. One common practice among navigators up to the late nineteenth century was to use both a sextant and an octant. The sextant was used with great care and only for lunars, while the octant was used for routine meridional altitude measurements of the sun every day. This protected the very accurate and pricier sextant, while using the more affordable octant where it performs well.

The first compasses in Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) in China were made of lodestone, a naturally magnetized ore of iron in the shape of a spoon. The compass was later used for navigation by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Later compasses were made of iron needles, magnetized by striking them with a lodestone. Dry compasses begin appearing around 1300 in Medieval Europe. This was supplanted in the early 20th century by the liquid-filled magnetic compass.

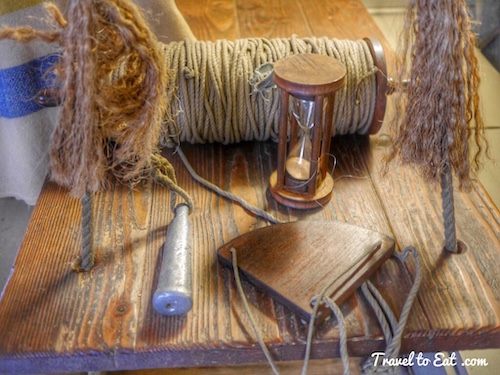

The little gadget shown above is called a ship log, and it is a way of determining the speed of the boat through water. This is the evolved form of throwing a chip of wood overboard and seeing how far it goes in a few seconds. In the above picture you can see a thirty second sandglass. The idea is to throw it overboard, let it float there for 30 seconds, while the ship moves away. The line has knots on it every so often and thus you can measure the speed of the boat. You can use the same line to measure depth with a lead plumb bob.

Chronometers were used on board ships to accurately tell the time and determine longitude. Chronometers were very expensive in the 19th century and were purchased by the Admiralty to be loaned to ship captains for special voyages or exploration. This Victorian chronometer comes with its own mahogany box with a protective glass inner lid and was number 2112 issued by Hewitt and Son, Makers to the Admiralty, London. A major function of the Royal Observatory was to organize a contest entitled the Greenwich Trial which was held annually after 1822 and which allowed the Admiralty to choose the best chronometers available. Winners could place the title “Makers to the Admiralty” on their chronometers. Between 1853-1858 they were unable to win with any chronometers they entered, including number 1999 which they entered four times, indicating they were not held in especially high regard by the Admiralty although the chronometers were probably sold to private companies.

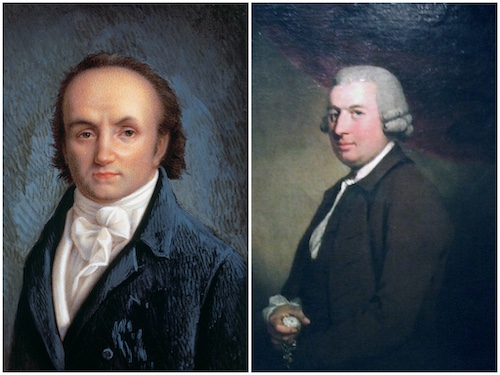

John Arnold (1736-1799) was the first to design a watch that was both practical and accurate, and also brought the term “Chronometer” into use in its modern sense, meaning a precision timekeeper. His technical advances enabled the quantity production of Marine Chronometers for use on board ships from around 1782. Arnold and Son dominated the early purchases of chronometers by the Admiralty. The basic design of these, with a few modifications unchanged until the late twentieth century. With regard to his legacy one can say that both he and Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) largely invented the modern mechanical watch.

Immortalized by Charles Dickens in ‘Dombey and Son’ where ‘the sign of the little midshipman’ hung above the shop kept by Sol Gils, figures such as this once marked many shops of instrument makers and navigation warehouses of 18th and 19th century England, America, and Europe. Young naval officers were expected to equip themselves with navigational instruments from such shops. The figure represents a British naval lieutenant in full dress uniform of the period 1787-1812 and he holds an octant. I know this was a long post but as always I hope you enjoyed it. Please leave a comment.

[mappress mapid=”113″]

References:

Princeton Sextants: http://libweb5.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/pacific/introduction/introduction.html

HMS Sirus: http://norfolkislandmuseum.com.au/collections/hms-sirius/

VOC Zuytdorp: http://www.museum.wa.gov.au/maritime-archaeology-db/wrecks/zuiddorp-zuytdorp

SMS Emdon: http://ahoy.tk-jk.net/macslog/GermanWW1LightCruiserSMSE.html

Samuel Plimsoll Ship: http://home.pacific.net.au/~hannahhome/ships/samuelplimsoll.html

Convict Records for the York: http://www.convictrecords.com.au/ships/york/1830

History of Compass: http://theinstitute.ieee.org/technology-focus/technology-history/a-history-of-the-magnetic-compass

Chinese Compass:

Chronometers British Navy: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00253359.2013.766998

Accounts of the House of Commons 1859 page 23-24

Arnold and Son History: http://www.arnoldandson.com/home/history/chronology.aspx

Abraham-Louis Breguet: http://www.breguet.com/en

French Maritime Instruments: /french-maritime-museum-navigation-instruments-paris/

Astrolabes, Clocks and Sundials: /astrolabes-and-sundials-musee-des-arts-et-metiers-paris/