For me and apparently many others, Vermeer is a guilty pleasure. His paintings are so few and so small that it is hard to get enough of them. I sometimes find myself looking, when we travel, to see if any museums in the area have a Vermeer. Fortunately for me, the Louvre has two. I often wonder why a similar small masterpiece, the Mona Lisa has such a large crowd perpetually glued to it’s location while these two small, but exquisite paintings are usually left to themselves. If you visit the Louvre, spend time with with these paintings, the pleasure will last long after you leave. Normally I photograph with the frame, but because these are so small, so beautiful and so loved by everyone, I have enlarged just the painting for both.

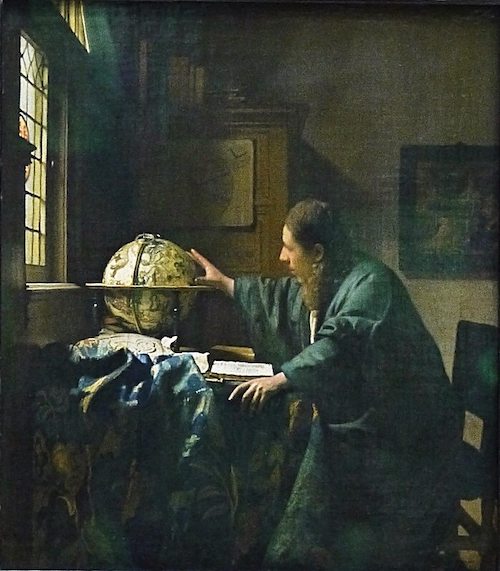

The Astronomer pictured above is a painting finished about 1668. It is oil on canvas, 51 cm x 45 cm (20 x 18 in), and is on display at the Louvre, Paris. Portrayals of scientists were a favorite topic in 17th century Dutch painting and Vermeer’s oeuvre includes both this astronomer and the slightly later The Geographer. Both are believed to portray the same man, possibly Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Surprisingly both were originally sold together. The presumed buyer was Hendrik Sorgh, whose estate sale held in Amsterdam on 28 March 1720 included both The Astronomer and The Geographer.

The astronomer’s profession is shown by the celestial globe (version by Jodocus Hondius) and the book on the table, Metius’s Institutiones Astronomicae Geographicae). Symbolically, the volume is open to Book III, a section advising the astronomer to seek “inspiration from God” and the painting on the wall shows the finding of Moses—Moses may represent knowledge and science (“learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians”).

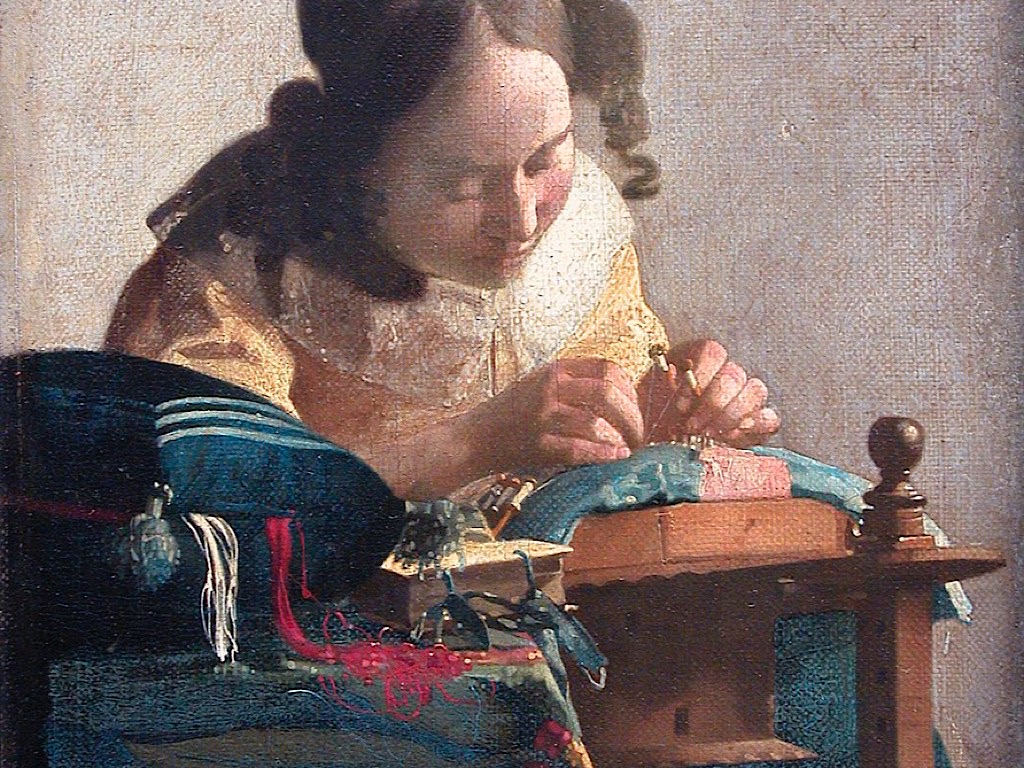

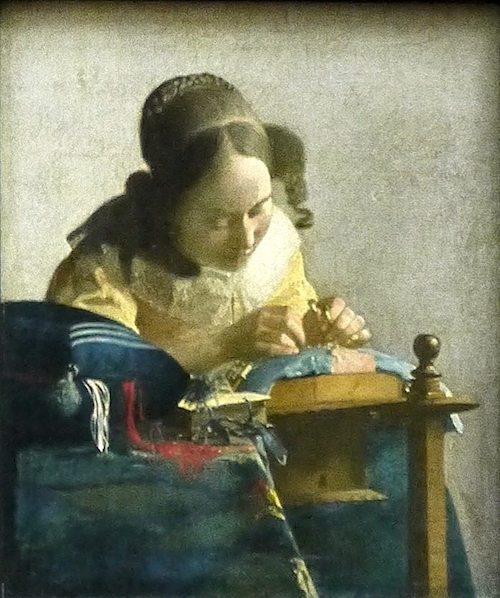

The Lacemaker is a painting by Johannes Vermeer and was executed as oil on canvas between 1669 and 1670. The dimensions are not more than 24.5 cm x 21 cm, i.e. 9.6 in x 8.3 in, which makes it actually the smallest among Vermeer’s paintings. In the intimate painting above, you can see how her handwork is illuminated by the sun streaming in through a window. Renoir considered this masterpiece, which entered the Louvre in 1870, the most beautiful painting in the world, along with Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera, also in the Louvre.

A young lacemaker, undoubtedly a member of the Delft bourgeoisie, is hunched intently over her work, deftly manipulating bobbins, pins and thread on her sewing table. The theme of the lacemaker, frequently depicted in Dutch literature and painting traditionally illustrated feminine domestic virtues. The small book in the foreground is probably the Bible, which reinforces the picture’s moral and religious interpretation. But this is also one of the peeks into domestic privacy that so fascinated him. He loved to observe the everyday objects around him and paint different combinations of them in his works: he used the same piece of furniture and Dutch carpet with leaf motifs in several of his pictures.

I like this interpretation of the painting by John Nash from 1991:

“Her diligence preserves her virtue: of that there is little doubt. Within easy reach of her right hand lies a book which is, surely, the Book, the Bible. But what is the work box doing there, so prominently placed; why should those threads of white and scarlet spill from it so copiously? The work box was known in Vermeer’s day as naaikussen which is, literally, a needle cushion. But naaien means, vulgarly and metaphorically, to copulate, and though the noun kussen means cushion, the verb kussen means to kiss. The threads that gush from the gape in this swollen naaikussen evoke the blood red and milk white spilling from the womb that precede the birth of a child.”

“Jan” Vermeer was born in the Netherlands in the city of Delft in 1632. His father was an innkeeper and a member of Saint Luke’s Guild which allowed him to sell art. His real profession, however was as a “caffawercker” (silkworker). Caffa was a kind fine satin widely used for clothes, curtains and furniture-covering. Some scholars have speculated that Vermeer’s predilections for this material, often depicted in his paintings, was a kind of childhood remembrance. The paintings in which his father dealt may have sparked in young Vermeer his interest in painting.

As with every other Dutch painter, Vermeer was required to undergo a six-year apprenticeship with a master painter who belonged to the Saint Luke’s Guild, the powerful trade organization which regulated the commerce of painters and artisans. For many years it was believed that Vermeer’s master was Leonaert Bramer of Delft. Bramer’s curious Italianate style was so different from both early and subsequent works of Vermeer that it would seem the elderly painter had little or no artistic influence on Vermeer. In any case, surviving documents indicate that Bramer had a friendly relationship with the Vermeer family.

With Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Vermeer ranks among the most admired of all Dutch artists, but he was much less well known in his own day and remained relatively obscure until the end of the nineteenth century. The main reason for this is that he produced a small number of pictures, perhaps about forty-five (of which thirty-six are known today), primarily for a small circle of patrons in Delft. Indeed, as much as half of Vermeer’s output was acquired by the local collector Pieter van Ruijven.

His works are rare. Of the 35 or 36 paintings generally attributed to him, most portray figures in interiors. All his works are admired for the sensitivity with which he rendered effects of light and color and for the poetic quality of his images. Vermeer, as many painters of his time, employed a very limited palette consisting of approximately ten to twelve pigments. The only substantial difference was his use of genuine ultramarine (pure lapis lazuli) rather than the much cheaper azurite. Genuine ultramarine is made of the powder of the crushed semi-precious stone lapis lazuli which, after being thoroughly purified by repeated washings, is bonded to a drying oil (walnut, linseed or poppy oil) through hand mulling. Though difficult to work with, it produces amazing lighting effects.

Vermeer’s copious use of genuine ultramarine seems to have reached an almost obsessive degree unless we understand just how perceptive was the artist’s eye. Vermeer realized early in his career that the admixture of genuine ultramarine with tones of gray, usually composed of lead white, bone black and raw umber in varying proportions, lends them a characteristic luminosity produced by intense daylight which cannot be produced otherwise. This technique is to found only in Vermeer’s paintings.

If you are truly in love with Vermeer, and I hope you are, and want to know more, there is no better resource than Essential Vermeer. I can only wish there was a website like this for all my favorite painters. You can find specific paintings and check on their travel and availability. There are interactive web displays and tons of beautiful art analysis of each of the paintings. I highly recommend this site.