The Tomb of Meketre (translates to The Sun is my protection) in western Thebe was a high official during the reign of Mentuhotep II, Mentuhotep III, Mentuhotep IV and Amenemhat I which spanned the 11th and 12th Dynasties. He served as Overseer of the Six Great Law Courts, Treasurer and Chief Steward. He died during the early years of Amenemhat’s reign and was one of the last high-officials to be buried at Thebes before the royal court moved to Lisht. All the accessible rooms in the tomb of Meketre had been robbed and plundered during Antiquity; but early in 1920 the Museum’s excavator, Herbert Winlock, wanted to obtain an accurate floor plan of the tomb’s layout for his map of the Eleventh Dynasty necropolis at Thebes and, therefore, had his workmen clean out the accumulated debris. It was during this cleaning operation that the small hidden chamber was discovered, filled with twenty-four almost perfectly preserved models. Eventually, half of these went to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and the other half came to the Metropolitan Museum in the partition of finds.

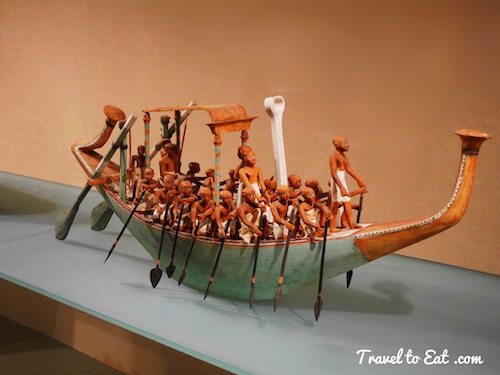

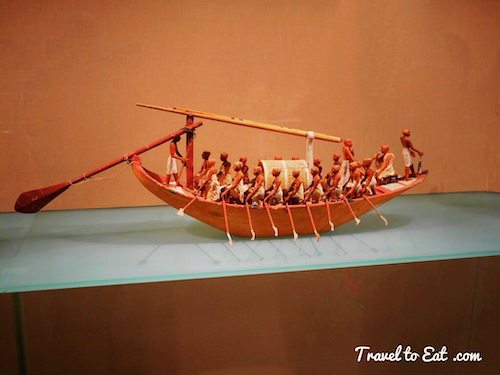

This boat is being paddled northward—downstream but against the prevailing wind—by sixteen men whose varied size and arm positions create an impression of movement along the line. The boat has two rudders because the elaborate stern would not accommodate the single rudder that was common to ordinary boats of the time. The rudders are fixed to poles capped by falcon heads. A statue-like figure of Meketre sits under a baldachin (canopy). The presence of a large libation vase indicates that an offering ritual is being performed. Facing Meketreis one of his sons or an upper servant with arms crossed reverentially over his chest. The shape of the boat, the baldachin, and the vase testify to the funerary nature of the voyage. Quite possibly, we are seeing Meketre on a pilgrimage to Abydos, the sacred site of Osiris, the god of the underworld. Note that all figures on this boat have shaven heads.

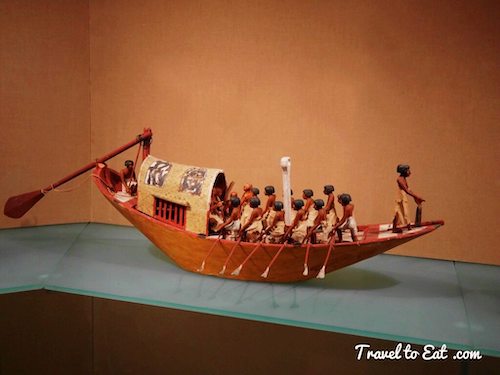

Meketre is seated smelling a lotus blossom in the shade of a small cabin, which on an actual boat would have been made of a light wooden framework with linen or leather hangings. Here the hangings are shown partly rolled up to let the breeze into the cabin. Wooden shields covered with bulls’ hides are painted on each side of the cabin roof. A singer, with his hand to his lips, and a blind harper entertain Meketre on his voyage. Standing in front of him is a man, probably the ship’s captain, with his arms crossed over his chest. He may be depicted awaiting orders, but he may also be paying homage to the deceased Meketre. As the twelve oarsmen propel the boat, a lookout in the bow holds a weighted line used to determine the depth of the river. At the stern, the helmsman controls the rudder. A tall white post amidship supported a mast and sail (not found in the tomb), which would have been taken down when the boat was rowed downstream—as it is here—against the prevailing north wind. Going south (upstream), with the wind behind it, the boat would have been sailed.

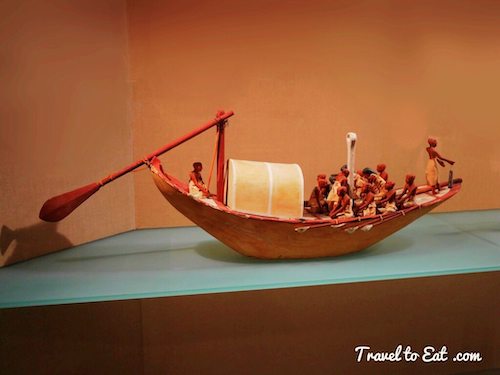

Many outings of Egyptian nobles culminated in a picnic. On the menu for Meketre’s boat trip were roasted fowl,dried beef, bread, beer, and some kind of soup. Meat and bread were carried on another tender, now in Cairo. Here, the beer is prepared and the soup cooked. A blackened trough may have contained burning coal forroasting the fowl. A man tends a stove on which soup simmers. On either side, a woman grinds grain. Brewers inside the cabin are shaping bread loaves, then working them through sieves into large vats. One brewer stands in another vat, where he tramples the dates that provide the sugar for the fermentation of the beer. The oars of this boat are fixed to the sides; to avoid damaging the oars while the boats were transported and deposited in the model chamber, all oars of Meketre’s boats were secured in this manner.

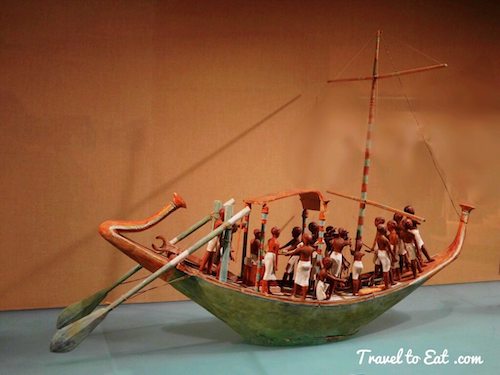

This boat is being rowed in a northerly direction, downstream, against the prevailing north wind. Its mast and spars rest in the forklike support beam, ready to be rigged for the return journey. The sail lies folded on the deck. A small cabin, positioned amidships, leaves room for eighteen rowers; speed clearly is important on this journey. Seated on a stool in the prow, Meketre holds a closed lotus flower to his nose. Before him stands a man (possibly the boat captain), with arms crossed referentially over his chest. Inside the cabin, a servant guards Meketre’s trunk. Is the Chief Steward on an inspection tour for the pharaoh, and does the trunk contain the accounts? Even if this represents a real-life event, the model still refers to the afterlife because the lotus flower, which opens every morning when the sun comes up, is a symbol of rebirth.

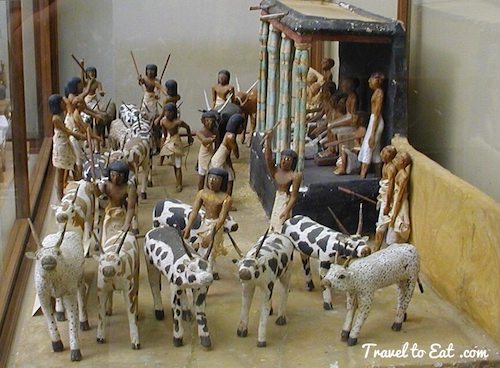

These models are highly valued because of the exquisite carving and painting and because they are remarkably well preserved. The colours, the linen garments on some of the figures, and most of the twine rigging on the boats are original. They tell us in great detail about the raising and slaughtering of livestock, storage of grain, making of bread and beer, and design of boats in Middle Kingdom Egypt. On another level of meaning, they tell us about the Egyptian belief that images could magically provide safe passage to the afterlife and eternal sustenance once there. Because of limited space, only the models above were on display when I visited. I found another collection on Wikipedia that shows dioramas of A garden, making bread and beer and a livestock market.

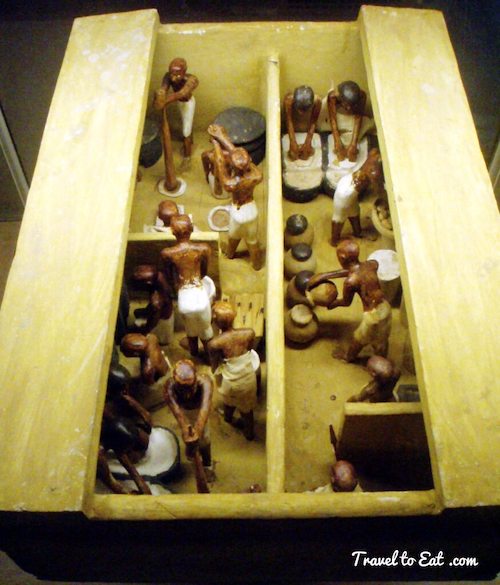

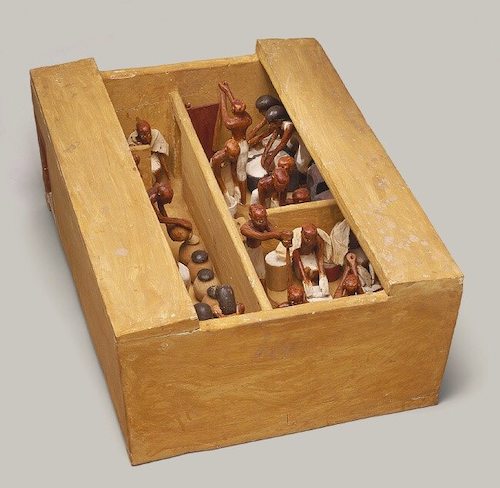

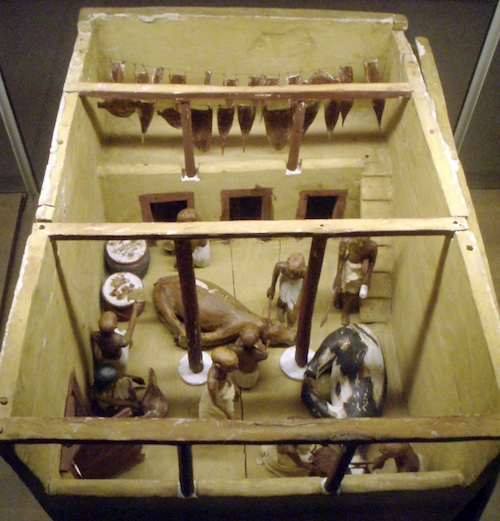

This model of a granary was discovered in a hidden chamber at the side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the royal chief steward Meketre, who began his career under King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II of Dynasty 11 and continued to serve successive kings into the early years of Dynasty 12.The four corners of this model granary are peaked in a manner that is sometimes still found in southern Egypt today presumably to offer additional protection against thieves and rodents. The interior is divided into two main sections: the granary proper, where grain was stored, and an accounting area. Keeping track of grain supplies was crucial in an agricultural society, and it is noteworthy that the six men carrying sacks of grain here are outnumbered by nine men taking care of measuring and accounting. Of the four scribes two are using papyrus scrolls, two write on wooden writing boards.

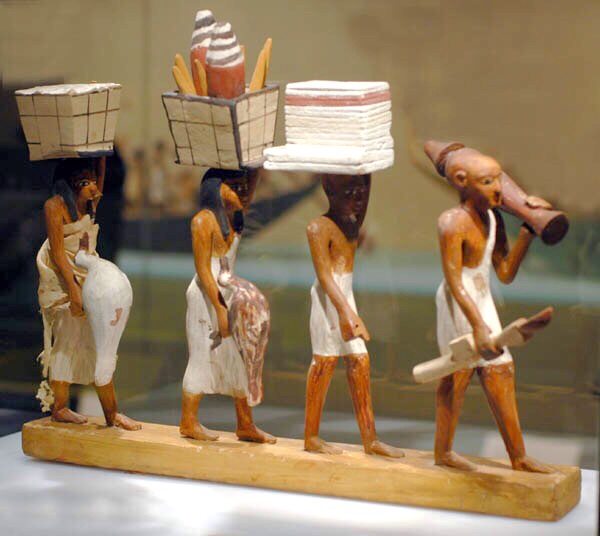

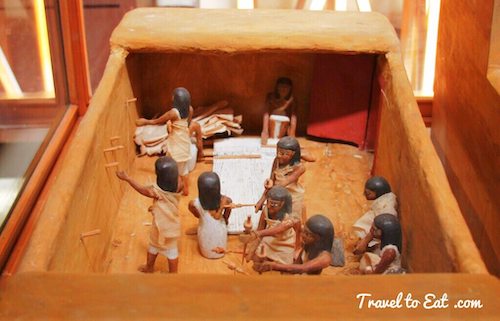

The figures in Meketre’s models, especially those from the combined bakery and brewery, are small works of art in their own right. Although several figures in a given model may be performing the same task, each is a distinct individual, and each has a slightly different pose.The most striking aspect of Meketre’s brewers is their arms, which were specially crafted for each figure according to the task he performs. These figures and those in Meketre’s other models convey a feeling of motion that was seldom achieved, or desired, in more formal Egyptian statuary. Note particularly the pose of the man decanting beer at the right.

This masterpiece of Egyptian wood carving was discovered in a hidden chamber at the side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the royal chief steward Meketre. Together with a second, very similar female figure (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo) this statue flanked the group of twenty two models of gardens, workshops, boats, and a funeral procession that were crammed into the chamber’s narrow space. Striding forward with her left leg, the woman carries on her head a basket filled with cuts of meat. In her right hand she holds a live duck by its wings. The figure’s iconography is well known from reliefs of the Old Kingdom in which rows of offering bearers were depicted. Place names were often written beside these figures identifying them as personifications of estates that would provide sustenance for the spirit of the tomb owner in perpetuity. The woman is richly adorned with jewelry and wears a dress decorated with a pattern of feathers, the kind of garment often associated with goddesses. Thus, this figure and its companion in Cairo may also be associated with the funerary goddesses Isis and Nephthys who are often depicted at the foot and head of coffins, protecting the deceased.

While there are no glittering jewels or gold, these exquisite figures are more valuable than a whole bucket of gold. I love the little details of life four thousand years ago. In fact, Meketre may well have achieved the immortality through these little dioramas. Obviously any visit to New York deserves a visit to the Metropolitan Museum.

[mappress mapid=”63″]

References:

Tomb of Meketre: http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/metropolitan/pages/servant.htm

Tomb of Meketre: http://www.odysseyadventures.ca/articles/thebes/article_meketre.htm

Granary: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/545281

Wikipedia Commons: http://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Tomb_of_Meketre