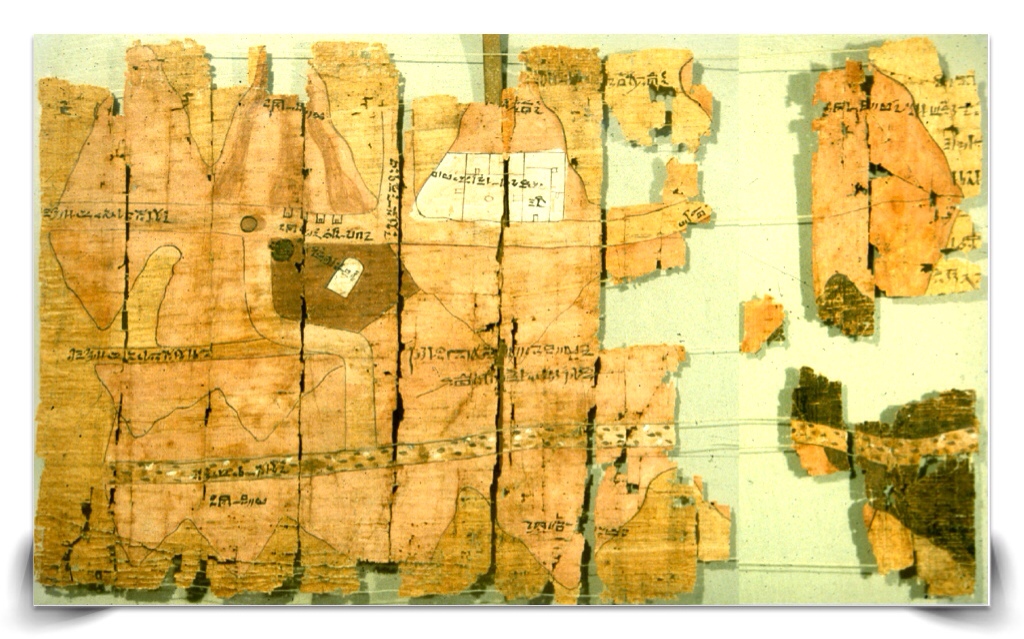

Everyone would love to find a treasure map. The Turin Papyrus Map is an ancient Egyptian treasure map, generally considered the oldest surviving topographical and geological map from the ancient world. It shows the locations of gold and slilver mines, where to quarry the prized bekhen-stone and it also depicts roads to the Dead Sea port used to travel to the fabled Punt, a place with even more gold. Punt was also really famous as the source of the biblical Frankincense and Myrrh, worth its weight in gold and used by the ancient Egyptians, along with natron, for the embalming of mummies and temple ceremonies. Although there are a few older topographic maps from outside Egypt, they are all quite crude and rather abstract in comparison to the relatively modern looking map drawn on the Turin papyrus.

The map was drawn about 1160 BC by the well-known Scribe-of-the-Tomb Amennakhte, son of Ipuy. Apparently his hieroglyphic cursive style is so distinctive there’s no doubt when an archaeologist sees it, could someone identify you after four thousand years by your handwriting? It was prepared for Ramesses IV’s quarrying expedition to the Wadi Hammamat in the Eastern Desert. According to the inscription on the map, this included 8,362 men, which makes it the largest recorded quarrying expedition to Wadi Hammamat (Valley of Many Baths) after one about 800 years earlier during the Middle Kingdom’s 12th Dynasty. Most likely, it was drawn as a visual record of the expedition to be viewed by either Ramesses IV or Ramessenakhte, the High Priest of Amun in Thebes, who organized the expedition for the king. The village where Amennakhte’s house and tomb were found is Deir el-Medina, home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th dynasties of the New Kingdom (1550–1080 BC). Tomb builders, artists, craftsmen and their families lived there during a period of about 400 years, leaving a rich record of daily life in that era. The Turin Papyrus was found in Amennakhte’s family’s private tomb, by the notorious Bernardino Drovettithe, the back of which was re-used by Amennakhte. In 1824, King Charles Felix of Sardinia acquired much of the personal collection of Drovetti, including this map, which went to the University of Turin and formed the foundation for the Museo Egizio in Turin.

The map shows a 15 km stretch of Wadi Hammamat in the central part of Egypt’s Eastern Desert about 70 km from Thebes. The top is oriented toward the south and the source of the Nile River with west on the right side, and east to the sea is left. Geologists James A. Harrell and V. Max Brown also noted that the colors were apparently not added for esthetic reasons, they said the colors ”correspond with the actual appearance of the rocks making up the mountains.” Sedimentary rocks in one region, which range in color from purplish to dark gray and dark green, are mapped in black. Pink granite rocks correspond with the pink- and brown-streaked mountain on the scroll. The scroll notes the locations of the mine and quarry, the gold and silver content of surrounding mountains, the settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir (well of the mother of pottery) and the destinations of the roadways. The streaks may thus represent the iron-stained, gold-bearing quartz veins that the ancient Egyptians were mining, or they may depict mine tailings. The first of the roads is labelled “The road that leads to Yam”, which heads southeast towards the port of Quseir. The second road is simply “Another road that leads to Yam”, exact destination unknown. The third road is described as “road of Ten-pa-mer”, which means “the road belonging to the harbor”.

The actual purpose of this particular expedition was to obtain blocks of stone to be used for statues of the king. These include basalts, schists, quartz with gold and bekhen-stone, an especially prized gray to green sandstone used for bowls, palettes, statues, and sarcophagi. Green (ancient Egyptian name ‘wahdj’) was the color of fresh growth, vegetation, new life, and resurrection (the latter along with the color black). The hieroglyph for green is a papyrus stem and frond. No wonder they used green for their sarcophagus.

Contrary to popular beliefs, the amount of gold produced and used in ancient Egypt was small, accounting for its strictly limited Royal and religious use. The annual production of gold during pharaonic times is thought not to have exceeded one ton per year. The funeral mask for King Tutankhamun alone weighed 232 pounds. The Egyptian word for gold is nub, which survives in the name Nubia, which was the main center of production. Over one hundred ancient small gold quarries have been discovered in Egypt, mostly in the desert valleys to the east of the Nile. There were two sources of gold, one called nub-en-set (gold of the mountain) and the other called nub-en-mu (gold of the river). The gold in the river sand was extracted using sheepskins, perhaps leading to the Greek legend of the Golden Fleece. Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper and other metals called white gold by the Greeks which was also found in the mines.

Gold was considered by the ancient Egyptians to be a divine and indestructible metal. It was associated with the brilliance of the sun. The hieroglyph for gold represents a golden collar with beads on its lower edge and hanging ends. The “Golden Horus” hieroglyph which was part of the five royal titularies consisted of the falcon of Horus above the gold symbol. An inscription of the 12th Dynasty describes the golden Horus hieroglyph as the “name of gold”. The notion of “gold” is strongly linked to the notion of “eternity”. The royal tomb was called the “House of Gold” during the New Kingdom not only because it was stacked up with gold, but because it was there for eternity. The “golden Horus name” may convey the same notion of eternity, expressing the wish that the king may be an eternal Horus. On the Rosetta Stone (see my post) the silver symbol (hedj in Egyptian), seen to the right above, which is a derivation of the gold symbol, is used three times to represent taxes.

Let us return to that road of Ten-pa-mer, leading to the harbor, the real treasure in this story. That ancient harbor turned out to be Saww on the Red Sea. The massive complex, made up of six manmade caves, is located at Wadi Gawasis, a small desert bluff on the Red Sea near the modern city of Port Safaga. Mersa Gawasis is located on a fossil coral terrace at the northern end of Wadi Gawasis, above what is now the dry remains of an ancient bay that once flowed through a channel into the Red Sea. When Senusret’s men were here, the site was a sheltered lagoon, lush with mangroves, and deep enough for launching large ships to sail the Red Sea. Over the intervening millennia, nine feet of sand blew onto and covered the terrace slopes. But where were they going, the mysterious Punt of course. At times, the ancient Egyptians called Punt Ta netjer, meaning “God’s Land”. Carved in stone, scenes and texts tell of sailing expeditions sent south on the Red Sea to Punt and Bia-Punt (land of Punt) to acquire highly prized raw materials that were unavailable in Egypt: ebony, ivory, and gold; leopards, baboons, and other exotic live animals for the royal zoo; and the coveted aromatics frankincense and myrrh, required for use in temple ceremonies and some mortuary rituals.

Here, a team led by Kathryn Bard and Rodolfo Fattovich, during excavations beginning in 2004, revealed ship timbers, stone anchors, ropes, and other artifacts dating to the Middle Kingdom. They also uncovered actual products presumably brought from Punt, including ebony (identified by charcoal) and obsidian (a volcanic glass), neither of which occurs in Egypt.

They even found cargo boxes bearing painted hieroglyphic text describing the contents as the “wonders of Punt.” As we now know, this port was the jumping-off point for deep-sea voyages to Punt, some 1,200-1,300 km (800 miles) away to the south.

The most surprising find, Bard says, was what she calls “the rope cave,” containing an estimated 26 coils of ropes used for rigging that “looked to be in great condition, frozen in time,” just as they must have appeared when sailors left them on the cave floor nearly four thousand years ago.

In carved niches outside the second cave, the team discovered stelae, flat monuments made of limestone slabs, with badly eroded inscriptions. However, Bard found one, face down in the sand, that was “perfectly preserved,” she says. On it, hieroglyphic inscriptions recount two royal sailing expeditions, one to Punt and the other to Bia-Punt by two brothers. The text was the first evidence the team found that King Amenemhet III, who ruled Egypt 1831–1786 BCE, had dispatched such voyages. An inscription on a stone found on top of the cliff commemorating a voyage that set sail around 1950 B.C. lists a labor force of 3,756 men, 3,200 of them conscripted workers. “These were complicated and expensive operations in Egyptian times,” Fattovich says. Surprisingly, the harbor was only used for about 400 years, then abandoned.

The first mention of Punt was about 2500 B.C. during the reign of King Sahure, an expedition which returned with 80,000 measures of “ntyw”, which scholars believe to be myrrh and large quantities of electrum (mixture of gold and silver). Queen Hatshepsut’s expedition of five ships in the New Kingdom, if not the largest, was far and away the most thoroughly chronicled. Dispatched in the 15th century BC, during the ninth year of her reign, the crusade is meticulously recorded on bas-reliefs seen on the walls of Queen Hatshepsut’s stupendous temple of Deir el-Bahri. The inscriptions depict a trading group bringing back myrrh trees, sacks of myrrh, elephant tusks, incense, gold, various fragmented wood and exotic animals. The last expedition to Punt that we know of occurred under Ramesses III, in the 12th century B.C. An ancient papyrus records that Ramesses III “constructed great transport vessels … loaded with limitless goods from Egypt. … They reached the land of Punt, unaffected by (any) misfortune, safe and respected.” And they returned safe and respected. Apparently after that time, they traveled by land.

From the very beginning, the Egyptians were building boats that could be disassembled, and that makes them different from anyone else. They were using the shapes of the planks to lock each of the pieces into place. As the boat sat in the water, it swelled and became watertight, using very little caulking. The famous Khufu ship from around 2500 BC seen above gives us a very visual idea of shipbuilding at the time. It was built largely of Lebanon cedar planking in the “shell-first” construction technique, using unpegged tenons of Christ’s thorn. Expeditions to Punt were logistical feats of engineering, travel, and coordination on a gigantic scale, involving thousands of men. To build the ships, cedar timber was cut from the hills of Lebanon about 1,000 meters above sea level and brought down to the coast to be transported south on the Mediterranean to the Nile delta. There the timbers were loaded onto boats and transported upriver to a shipbuilding site at Coptos, where they were constructed into seafaring vessels. Ships would then be disassembled and their parts would be trekked by donkey caravan for approximately 10 days across 100 miles of desert, along with food, rope, pottery, and other travel supplies. Once at Wadi Gawasis, the ships would be reconstructed and readied to sail south on the Red Sea to Punt to gather Pharaoh’s treasure.

Florida State University maritime archaeologist Cheryl Ward has re-created a 66-foot-long, 30-ton reconstruction of an 18th Dynasty Egyptian trading ship. Called Min of the Desert–in honor of the powerful Egyptian fertility god commemorated in stelae and shrines at the Middle Kingdom lagoon site of Mersa Gawasis–the ship was partly based on a detailed relief depicting Hatshepsut’s fleet in her funerary temple.

So, where is Punt? On the original expeditions, wild animals including baboons were taken back to Egypt, as you can see above. The dry, hot climate did not agree with them and many died quickly. When the Egyptians observed baboons barking at the rising sun, they imagined that the apes were worshipping the sun just as people did. That’s why the baboon became an aspect of the sun god, Amun-Re, and whole colonies of these animals were kept in his temples. When they died, they were mummified and found their way to the British Museum. In 2010, a genetic study was conducted on the mummified remains of baboons that were brought back from Punt by the ancient Egyptians. Led by a research team from the Egyptian Museum and the University of California, the scientists used oxygen isotope analysis to examine hairs from two baboon mummies that had been preserved in the British Museum. The researchers found that the mummies most closely matched modern specimens seen in Eritrea and Ethiopia as opposed to those in neighboring Somalia, with the Ethiopian specimens “basically due west from Eritrea”.

So Punt was in modern day Eritrea but where was the actual port? A likely candidate is Adula in ancient Aksum. Aksum is mentioned in the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as an important marketplace for ivory, which was exported throughout the ancient world, and states that the ruler of Aksum in the 1st century AD was Zoskales, who, besides ruling in Aksum also controlled two harbours on the Red Sea: Adulis (near Massawa) and Avalites (Assab) located in Eritrea. Kathryn Bard has said her next project is to find the ancient harbor of Punt and perhaps soon we will know for sure.

The treasure I promised at the beginning of this long post is both physical and historical. The Turin Papyrus Map is a remarkable document, enriching our understanding of ancient Egypt. Egypt became a major gold-producer during the Old Kingdom and remained so in the next 1,500 years, with interruptions when the kingdom broke down. During the New Kingdom, the production of gold steadily increased, and mining became more intensive as new fields were developed. British historian Paul Johnson says that it was gold rather than military power which sustained the Egyptian empire and made it a world power throughout the third quarter of the second millennium BCE. Today these same ancient mines are being reopened with modern techniques, steadily increasing gold production in Egypt.

References:

Judith Weingarten: http://judithweingarten.blogspot.com/2011/09/hatshepsut-and-turin-papyrus-map.html

James Harrell: http://www.eeescience.utoledo.edu/faculty/harrell/egypt/Turin%20Papyrus/Harrell_Papyrus_Map_text.htm

Harrell Stone in Egypt: http://www.eeescience.utoledo.edu/faculty/harrell/egypt/Stone%20Use/Harrell_Stones_text.htm

What the numbers mean: http://www.eeescience.utoledo.edu/Faculty/Harrell/Egypt/Turin%20Papyrus/Harrell_Papyrus_Map_table-1.htm

Waddi Hammamat: http://egyptsites.wordpress.com/2010/09/14/wadi-hammamat/

Gold working and Mining: http://www.medal-project.eu/07-ancient_egypt.pdf

Gold Rush in Egypt: http://www.archaeology.org/9905/newsbriefs/gold.html

Veronica Scott: http://veronicascott.wordpress.com/2012/06/18/3000-years-later-we-know-his-work-by-his-heiroglyphic-handwriting/

Archaeogate: http://www.archeogate.it/spid/spid.php?cat=mersagawasis2&lang=it&theme=archaeogate

EgyptSitesBlog: http://egyptsitesblog.wordpress.com/tag/rock-inscriptions/

Scribd Kathryn Bard: http://www.scribd.com/doc/78257745/67/The-Middle-Kingdom-Overview