Ancient Egypt was very much a part of Africa's Neolithic period. Their word for luck was “sha” and “sha sha” meant bead. Egyptians used beads to cover almost every article of clothing and any uncovered part of the body. Quantities of beads were buried with the owner to ensure comfort in the afterlife. With reference to Neolithic Egypt, Lois Dubin wrote: No other civilization, however; manufactured such and enormous variety of beads in so many different materials. They were not only used for necklaces but were also attached to linen and papyrus backings to make belts, aprons, and sandals. Beadwork originated in Old Kingdom Egypt about 2200 BC.

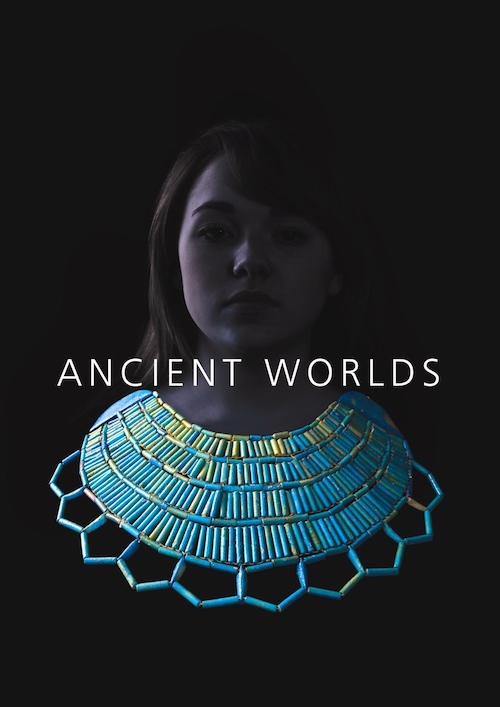

The Egyptian for collar was 'wesekh', which means 'wide'. The beautiful blue faience collar seen above is a First Intermediate Period faience broad collar from Sedment. The First Intermediate Period includes the time of 2216-2025 BC in ancient Egypt . Sedment is a village in what is now Egypt, at the entrance to Fayyum, about 70 miles south of Cairo. In its vicinity is an extensive necropolis. In research, these burial sites are known under the name “Sedment”. They probably belonged to several villages on the edge of the desert. The Manchester Museum houses over 16,000 objects from ancient Egypt and Sudan, making it one of the largest collections in Britain and one with world-class holdings in a number of areas. At the end of October 2012, the Museum opened its refurbished Ancient Worlds galleries, putting many more objects on display than ever before. The highlighted blue faience necklace is among the oldest Egyptian glass bead objects I could find. I really want to visit this museum.

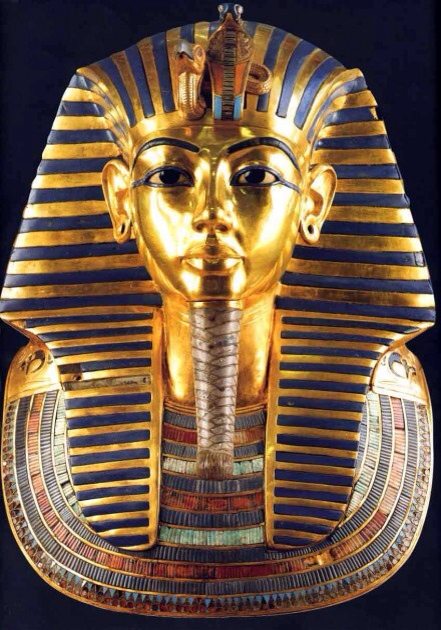

Tutankhamen was the son of Akhenaten and one of Akhenaten's sisters, or perhaps one of his cousins. As a prince he was known as Tutankhaten. He ascended to the throne in 1333 BC, at the age of nine or ten, taking the throne name Nebkheperure. The death mask is 24 pounds of solid gold, inlaid lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, turquoise, obsidian, and colored glass. Inside his innermost coffin Tutankhamen was buried with six collars, each with falcon heads at the ends. The top amazing example was found draped over the king's thighs. The collar has 11 main sections made of gold, as well as a counterweight. Each section has 8 rows of plaques, made of colored glass. The glass was meant to imitate semi-precious stones: light blue for turquiose, dark blue for lapis lazuli, and red for carnelian. The ninth row represents flower buds. The Corning Museum of Glass’s Research Scientist Emeritus, Dr. Robert Brill, was invited by a colleague at the National Gallery to examine the Tutankhamen Exhibition in 1976 for glass. One of Dr. Brill’s first impressions of the treasure was how prevalent glass was – appearing as inlays, molded objects, and beads. In a notebook, for example, Dr. Brill notes that the distinctive stripes on the nemes headdress on Tut’s golden funeral mask were created with blue glass inlay, not paint or lapis lazuli. Similarly, glass was inlaid in the false beard. Glass was used along with gold and precious gems in the scarab pectoral ornament found on the mummy’s chest. One of several headrests – which ancient Egyptians used instead of pillows – found in the tomb was made of blue glass.

The picture shows an unusual green glass in the scarab in the middle of the pectoral piece. In 1996 in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Italian mineralogist Vincenzo de Michele spotted an unusual yellow-green gem in the middle of another one of Tutankhamun's necklaces. Working with Egyptian geologist Aly Barakat, they traced its origins to unexplained chunks of green glass found scattered in the sand in a remote region of the Sahara Desert. It turned out to be from a meteor explosion about 26 million years ago, the heat melted the sand to make a green desert glass.

This colorful collar is made of faience (glass) beads, shaped and colored to look like the buds, petals, and fruits of various plants. The collar was made in the time of pharaoh Akhenaten, around 1353-1336 BC (just before Tutankhamun was born). Faience bead collars were frequently supplied as favors to guests at banquets. This necklace typifies the technical brilliance of the faience and glass jewelry of the Armana period (1379-1362 BC). It has been suggested that the uniquely gay and joyful quality of Amarna period art and jewelry reflects the sudden appearance of outside influences – possibly attributable to Minoan artists who may have fled to Egypt after the fall of Crete. Excavated from the tomb of Tutankhamen at Thebes.

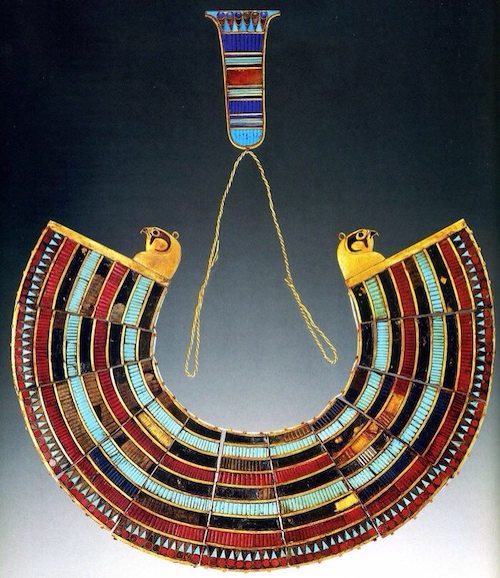

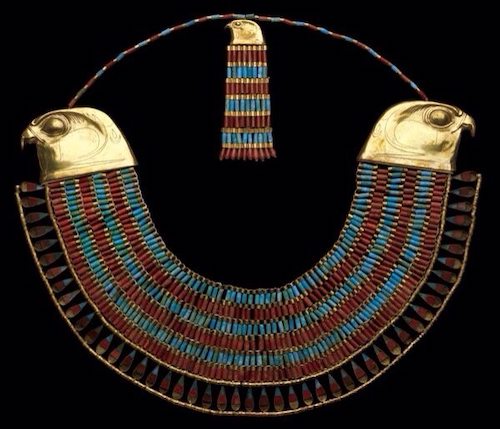

Inside his innermost coffin Tutankhamen was buried with six collars, each with falcon heads at the ends. This amazing example was found draped over the king's thighs. The collar has 11 main sections made of gold, as well as a counterweight. Each section has 8 rows of plaques, made of coloured glass. The glass was meant to imitate semi-precious stones: light blue for turquiose, dark blue for lapis lazuli, and red for carnelian. The ninth row represents flower buds.

This stunning necklace belonged to Princess Neferuptah of the 12th dynasty. It was found in her tomb, which was near the pyramid of her father, King Amenemhat III (who ruled around 1860-1814 BC). The collar is made of hundreds of beads, made from gold, carnelian, feldspar and glass paste. Once again there are flower buds at the bottom and falcon's heads at the ends, with a counterweight at the back. Because of its protective value, the wesekh (wide) collar was a favorite ornament of gods, kings and private individuals alike, hence, this collar accompanied Princess Neferuptah in her sarcophagus.

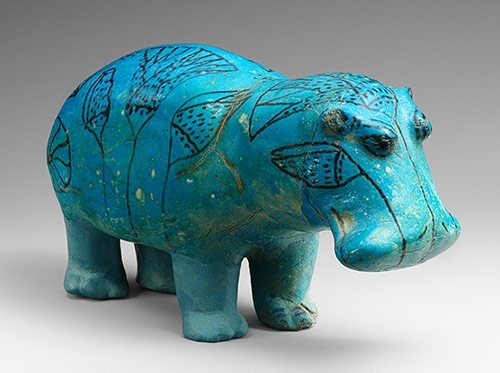

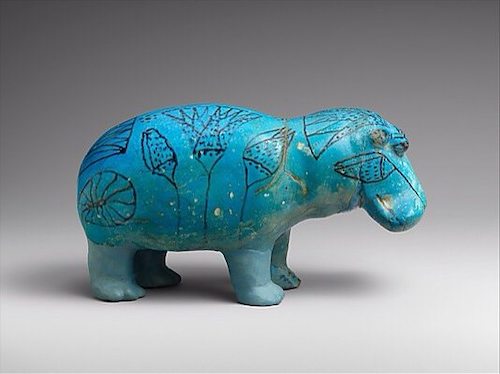

Egyptian faience is the oldest known type of glazed ceramic. It was first developed more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt, Mesopotamia and elsewhere in the ancient world. It is known for its bright colors, especially shades of turquoise, blue and green, and it can vary widely in appearance, from glossy and translucent to matte and opaque. Because it is composed mainly of silica (sand or crushed quartz), along with small amounts of sodium and calcium, faience is considered a non-clay ceramic. It is a precursor to glazed clay-based ceramics, such as earthenware and stoneware, and also to glass, which was invented around 2500 BC. Egyptian faience is a self-glazing ceramic: sodium in the wet paste comes to the surface as it dries and forms a glaze when it is fired in the kiln. This is called efflorescence glazing. Metal oxides in the paste color the glaze. Two common colorants are copper (turquoise) and cobalt (blue). Faience can also be created by placing small items such as beads in a container full of glazing powder (cementation glazing) or by painting on a glaze (application glazing). More than one glazing method may be used on a single piece. In the self-glazing process of efflorescence, the glazing materials, in the form of water-soluble alkali salts, are mixed with the raw crushed quartz of the core of the object. The idea of making a slurry to apply directly to the surface (application glazing) did not appear until around the New Kingdom (1550-1077 BC). As the water in the body evaporates, the salts migrate to the surface of the object to recrystallize, creating a thin surface, which glazes upon firing. In general, frits, glasses and faience are similar materials: they are all silica-based but have different concentrations of alkali, copper and lime. However, as Nicholson states, they are distinct materials because “it would not be possible to turn faience into frit or frit into glass simply by further, or higher temperature, heating.” In my reading the term “Frit” is used as the process to make “Faience”, as in “fritting”, although some authors seem to use the terms relatively interchangeably.

From the inception of faience in the archaeological record of Ancient Egypt, the colors of the glazes varied within an array of blue-green hues. Glazed in these colours, faience was perceived as substitute for blue-green materials such as turquoise, found in the Sinai peninsula, and lapis lazuli, from Afghanistan. According to the archaeologist David Frederick Grose, the quest to imitate precious stones “explains why most all early glasses are opaque and brilliantly colored” and that the deepest blue color imitating lapis lazuli was likely the most sought-after. As early as the Predynastic graves at Naqada, Badar, el-Amrah, Matmar, Harageh, Avadiyedh and El-Gerzeh, glazed steatite and faience beads are found associated with these semi-precious stones. To the Egyptians, faience was known as tjehnet, and more rarely as khshdj, the same word used for lapis lazuli. Both words are related to those for the properties of “shining,” “gleaming,” or “dazzling,” Faience was thought to glisten with a light symbolic of life, rebirth and immortality.

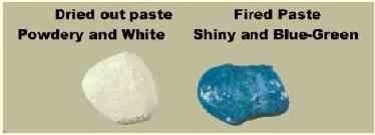

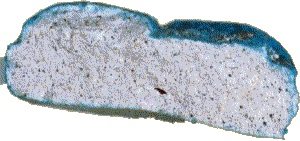

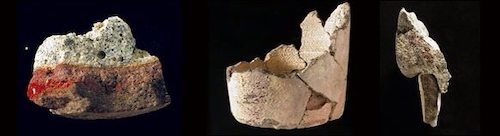

I found the above examples of making a Faience (or Frit) from Victor Bryant from UCLA, showing a simple faience recipe, the dried object with a fuzzy white surface and the final bright blue fired object. In the cross section seen above, you can see a thin layer of blue on the surface and a foamy white interior.

Archaeological research and replication experiments have shown that there were many recipes for Egyptian faience. These recipes varied by location and also over time. Above are some examples of different Egyptian faience recipes (these have all been fired just once and are glazed with the self-glazing efflorescence technique; the turquoise color is created by copper in the paste) from Amy Waller. In the bowl in the bottom right, an application glaze has been added, with a much darker blue color.

If you scrape the blue glazed layer off, you get an blue pigment called Egyptian Blue, which can be used as a paint or to re-glaze ceramic objects. Egyptian Blue, also known as calcium copper silicate (CaCuSi4O10 or CaO·CuO·4SiO2) or cuprorivaite, is a pigment used by Egyptians for thousands of years. It is considered to be the first synthetic pigment. The pigment was known to the Romans by the name caeruleum, kyanos to the ancient Greek-Mycenaean-Minoans. After the Roman era, Egyptian Blue fell from usage and the manner of its creation was forgotten. The earliest evidence for the use of Egyptian blue is in the 4th Dynasty (c.2575–2467 BC), limestone sculptures from that period in addition to being shaped into a variety of cylinder seals and beads. In the Middle Kingdom (2050–1652 BC), it continued to be used as a pigment in the decoration of tombs, wall paintings, furnishings and statues and by the New Kingdom (1570–1070 BC), began to be more widely utilized in the production of numerous objects. Its use continued throughout the Late period, and Greco-Roman period, only dying out in the 4th century AD, when the secret to its manufacture was lost. Egyptian Blue is a form of Frit and in antiquity, frit could be crushed to make pigments or shaped to create objects. The foamy white center may also have served as an intermediate material in the manufacture of raw glass. The definition of frit tends to be variable and has proved a thorny issue for scholars.

Archeologists think glassmaking originated in the Syro-Palestine area around the third millennium BC and was developed in Egypt around 1800 BC. The Phoenicians became the greatest glassmakers and exporters of the ancient world. This was because of the rich deposits of silica-based sand, which contained a substantial amount of lime, found along the coast of Lebanon. The reality may have been more complicated than first imagined, involving trade in glass ingots and molds. Archaeologists have uncovered for the first time the remains of a Bronze Age glass factory, where skilled artisans made glass from its raw materials. Surprisingly, this factory, which was bustling around 1250 B.C., is in Egypt rather than Mesopotamia, which is generally thought to be where glass was first made. The well-known site, Qantir-Piramesses, in the eastern Nile delta, flourished in the 13th century B.C. as a northern capital of the pharaohs. Glass was extremely valuable during the Bronze Age, so this discovery implies that Egypt may have enjoyed more clout than was previously thought as a producer of this sought-after substance. Note the foamy white glass ingot in the above photo which is the center substance of Faience.

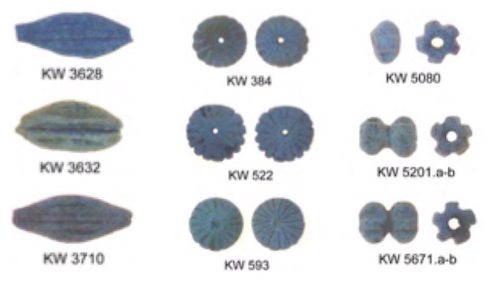

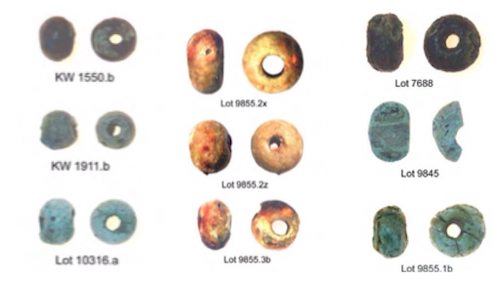

Probably the earliest beads of true glass were made by the winding method. Glass at a temperature high enough to make it workable, or “ductile”, is laid down or wound around a steel wire or mandrel coated in a clay slip called “bead release.” The wound bead, while still hot, may be further shaped by manipulating with graphite, wood, stainless steel, brass, tungsten or marble tools and paddles. This process is called marvering, originating from the French word “marver” which translates to “marble”. It can also be pressed into a mold in its molten state. While still hot, or after re-heating, the surface of the bead may be decorated with fine rods of colored glass called stringers. A Late Bronze Age Egyptian shipwreck, discovered off the Turkish coast at Uluburun in 1982, dates to approximately 1300 BC. Thousands of beads, both faience and glass seen above, were found on the shipwreck, including approximately 75,000 faience beads and 9,500 glass beads.

An Akkadian text from Assurbanipal’s library at Nineveh, in the 7th century BC, suggests that a frit-like substance was an intermediate material in the production of raw glass. This intermediate step would have followed the grinding and mixing of the raw materials used to make glass. An excerpt of Oppenheim’s translation of Tablet A, Section 1 of the Nineveh text reads: “You keep a good and smokeless fire burning until the ‘metal’ (molten glass) becomes fritted. You take it out and allow it to cool off.” The steps that follow involve reheating, regrinding and finally gathering the powder in a pan. Following the Nineveh recipe, Brill was able to produce a “high quality” glass. He deduced that the frit intermediate is necessary so that gases will evolve during this stage and the end product will be virtually free of bubbles. Furthermore, grinding the frit actually expedites the “second part of the process, which is to…reduce the system to a glass.” The picture above is a glass Frit or ingot ready for trade or to be ground to a powder and with additional alkali, to be turned into true glass.

It is, at present, impossible to say with any real confidence whether the production of faience appeared in Western Asia before it did in Egypt; comparative chronologies are still too imprecise for the question to be resolved. In Egypt beads of green or greenish-blue glazed steatite (perhaps also of other stones) appear first in the Badarian period (Early Predynastic), currently dated to the last quarter of the fifth millennium BC or soon after. Glazed stones, predominantly steatite (soapstone), continued as one of the commoner materials for beads in Pre-dynastic Egypt. Soapstone is soft and easy to carve in its native state but becomes much harder and self-glazes when fired in a kiln. Green-glazed faience beads appear first in the Amratian period (Naqada I; Middle Predynastic). c.4000-3500 BC, though not as commonly as was once assumed.

I feel the need to summarize this relatively long and complex post. It is likely that the first glazed vessels were created by non-clay faience in which the glaze was not applied but instead was self glazing by efflorescence glazing. Beads were some of the first glazed objects, beginning with steatite or soapstone in the fifth Millenium BC. Glass paste or faience appeared around 4000-3500 BC particularly in blue, possibly in a direct connection with copper kilns, which would have had all the necessary components (sand, ash and copper) to fortuitously create blue faience. Further developments were applied glazes to ceramic and clay vessels and true glass by the second millennium BC. This in turn stimulated a luxury trade in raw Frit or glass ingots, beads and finished glass products, all of which were literally worth their weight in gold, to destinations throughout the Middle East and Greece. Thank you for your patience; I really hope you enjoyed the post.

References:

Glass in Mesopotania and Egypt: http://www.iprospero.com/shpusa/books/chapters/Alchemy_of_Glass.pdf

Chemical Composition of Egyptian Glass: http://www.antiquityofman.com/AE_glass.html

Archaeologists Discover an Ancient Egyptian Glass Factory: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/21/science/21glas.html?_r=0

NBC News Qantir: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/8221331/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/how-egypt-turned-dust-treasures-glass/#.UvCG6X-9KK0

Collars: http://www.timetrips.co.uk/ef-collars.htm

Shipwreck Glass Beads: http://anthropology.tamu.edu/papers/Ingram-MA2005.pdf

Corning Museum of Glass: http://blog.cmog.org/2012/04/03/glass-of-king-tut-dr-brills-research-on-the-ancient-egyptian-glass-from-tutankhamuns-tomb/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=glass-of-king-tut-dr-brills-research-on-the-ancient-egyptian-glass-from-tutankhamuns-tomb

Libyan Glass: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5196362.stm

History of Beads by Dubin: http://www.amazon.com/The-History-Beads-Present-Expanded/dp/0810951746

Gallery Ezakwantu: http://www.ezakwantu.com/Gallery%20Trade%20Beads%20Slave%20Beads%20African%20Currency.htm

P.T. Nicholson and E. Peltenburg 2000, “Egyptian Faience,” In: P.T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 178.

R.H. Brill 1970, “The Chemical Interpretation of the Texts,” In: A.L. Oppenheim et al. (eds.), Glass and Glassmaking in Ancient Mesopotamia, Corning: The Corning Museum of Glass, 113.

Early Frits and Glazes: http://www.ceramicstudies.me.uk/histx104.html

Amy Waller: http://www.amywallerpottery.com/faience

UCLA Faience Technology: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/9cs9x41z#page-2