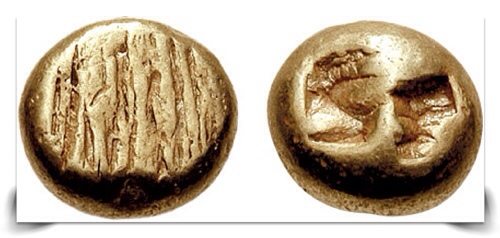

Coins are ubiquitous in modern society, check your pocket and you will undoubtedly find a few right now. Have you ever wondered when the first coins were made? An exhibition at the British Museum tries to answer that exact question. The 1/6 stater, pictured above, is more than 2,700 years old, making it one of the very earliest coins. It was made from electrum, a natural occurring alloy of gold and silver which I discussed in a previous post on Egyptian gold. It was discovered in Ephesos, an ancient Hellenic city in the area of Lydia, known from the bible and a prosperous trading center on the coast of modern day Turkey. The Lydians were the first to have fixed retail shops, probably contributing to the development of the coins. The coin above looks like a tiny nugget with a design on one side only. This ancient stater was hand struck. A die with a design, in this case a lion’s head, for the front of the coin was placed on an anvil. A blank piece of metal was placed on top of the die, and a punch hammered onto the reverse. The result was a coin with an image on one side and a punch mark on the other. Even though it looks crude, the weight was strictly monitored.

These striated designs are thought to be the oldest electrum coins, around 630-650 BC. We think they were differentiated in common use by the punch marks on the back although the smaller denominations might have been weighed. The electrum coins came into being to solve a local problem, the percentage of gold in the electrum varied from 30-70%. Thus the coins were guaranteed by the king to be worth a certain amount, making them easier to trade. The electrum coins were used for about 80-100 years until they figured out how to separate the gold and silver in electrum.

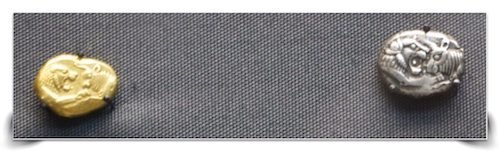

This rare electrum coin has a Greek inscription. Many of the designs that occur on early coins bear a remarkable resemblance to seals (stamps). Apparently these markings were attempts to guarantee the quality of the metal in the coins. The inscription on this extremely rare coin seems to confirm this interpretation. It is written right-to-left with mirror-image Greek letters, and translates “I am the badge of Phanes”. It is not known who Phanes was but he was presumably a powerful and wealthy individual whose name conjured up trust in the community that used these coins. The appearance of the stag on the coin has led some to attribute this coin to the city of Ephesos, where there was a strong cult of Artemis, to whom the stag was sacred.

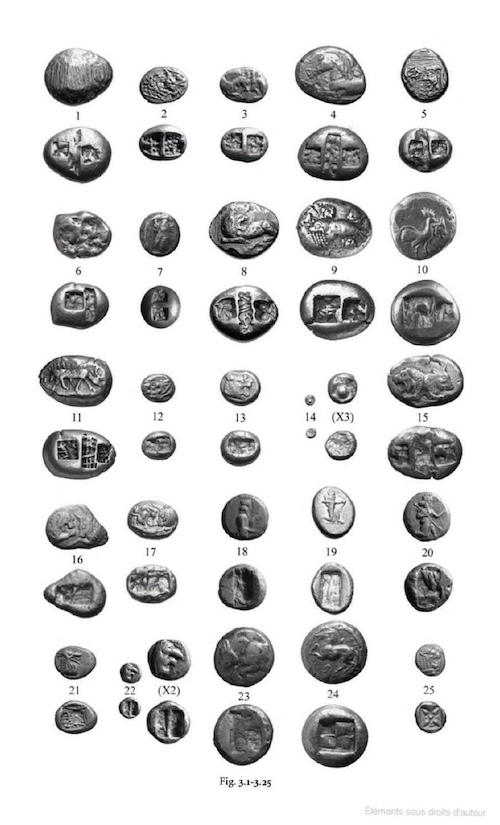

Apparently it was King Croesus who discovered how to separate the gold and silver from electrum and it is these metals which came to be used widely in coinage. Coins made from electrum had been struck since the seventh century BC in Lydia, but this practice was superseded by currencies made from gold and silver. Possibly because of his legendary wealth, the earliest coins to be issued in gold have often been attributed to the last and most famous Lydian King Croesus (560-546 BC). He was said to have panned gold from the nearby river Pactolus and introduced coinage of pure gold and pure silver. Crucibles and a few gold objects have made conclusive evidence for the gold-refining process from the 6th century B.C. for modern archaeologists. The expression “as rich as Croesus” is used today to mean fabulously rich. A lion was shown facing a bull on the front, while the reverse consisted of simple punches produced by a hammer blow.

The coins were issued in several denominations in gold and also in silver. It cannot have been easy to tell some of the smaller denominations apart. We must assume that for many transactions the coins were weighed rather than counted.

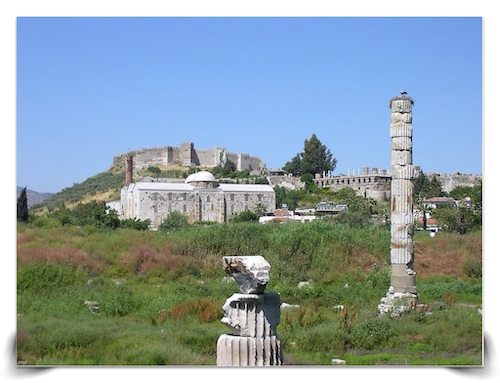

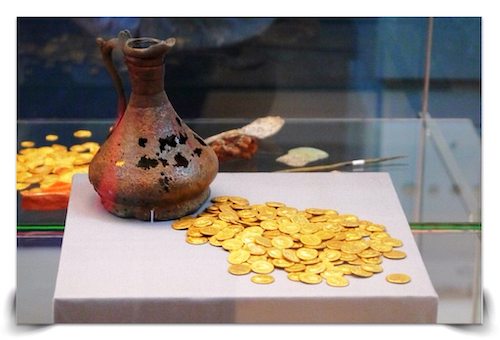

But how do we know how old the coins are? Excavations carried out by The British Museum at the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in 1904-5 provided the breakthrough of in the form of a number coins sealed in the foundation deposit of the Archaic temple.

This is a black and white photograph of the coins in the jug. The originals are still in Turkey, the ones on display are copies.

From the date of this early temple (around 600 BC) we know for certain that the coins were in use at this point in time. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, stated that “the Lydians were the first people we know to have struck and used coinage of silver and gold.” The gold and sliver and were found in the form of electrum in the Pactolus river.

Lydia does not have many marvelous things to write about in comparison with other countries, except for the gold dust that is carried down from Mount Tmolus.

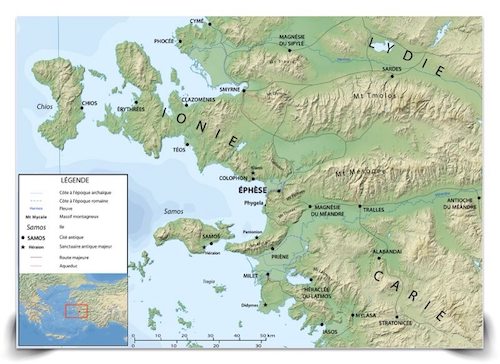

As early as the thirteenth century BCE, the Aegean shores of modern Turkey were occupied by Greeks. In the Bronze age, they were divided into three groups: the Aeolians in the north, the Ionians in the center (around Ephesus and Miletus) and the Dorians in the south, opposite Caria (main town Halicarnassus). The Phrygians had arrived over the Caucasus Mountains in the 13th Century BC, and conquered the Hittite Empire, already weakened by Assyria, and expanded before being checked by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (1114-1076) who refers to the “Muški” he defeated near the Euphrates, a name later applied to the Phrygians. Hattušas, the Hittite capital, was burned by the Phrygians about 1200 BC, abandoned, and never reoccupied. A long “dark” period followed, but by the eighth century BC, the Phrygians had settled everywhere in Anatolia. The Phrygians of Gordium created a large kingdom, which occupied the greater part of Turkey west of the river Halys. The most famous king of Phrygia was Midas, who is known from Greek legends and perhaps also from contemporary Assyrian sources, which refer to an Anatolian ruler named Mit-ta-a. During his reign, a nomadic tribe called Cimmerians invaded the country, and in 710, Mit-ta-a was forced to ask for help from the Assyrian king Sargon II. Unfortunately, this did not prevent the Cimmerian invasion. In 695, Midas committed suicide after a lost battle. Archeology has confirmed that Gordium was destroyed and burned around that time. This time period corresponds roughly with the Babylonian World Map, see my post to learn more about the history of this period.

The people in antiquity had a mythological explanation for the presence of gold sand in the Pactolus river in Lydia. Bacchus offered Midas a gift, and the king asked that everything he touched be turned to gold. Soon realizing that he could neither eat nor drink, he asked to be relieved of the gift, and Bacchus sent him to wash it away in the Pactolus River. Midas, who was threatened by starvation, as everything he touched turned to gold, followed the advice of the compassionate god. He washed his head with his hair that had turned stiff with gold in the Lydian mountain river and was freed of the magic. According to legend, that was the reason why grains of gold are found in the sand of the Pactolus mountain river.

The Lydian Kingdom made Sardis its capital as early as 700 B.C. The river Pactolus ran right through the middle of town and emptied into the much larger Hermos river. What looks like a small muddy stream today was once a navigable river, smaller boats were either rowed or pulled by animals along the shore. The larger ships were moored about 6 kilometers downstream where the Pactolus meets the Hermos River, which flows into the Aegean Sea. The first king of the Mermnad Dynasty of Lydia was Gyges (687-652 B.C), credited with the invention of the first coined electrum coins. In excavations in the early 1980s, many coins were found in buildings of the Lydian period. Sardis was conquered by Persia in 546 BC, when King Croesus and Sardis fell to Cyrus the Great. Sardis formed the end station for the Persian Royal Road which began in Persepolis, capital of Persia.

Surprisingly, the Persians continued to mint coins in Sardis at least until 500 BC.

The Daric was a gold coin used within the Persian Empire and mentioned in the Bible. It was of very high gold quality, with a purity of 95.83%. Weighing around 8.4 grams, it bore the image of the Persian king or a great warrior armed with a bow and arrow, but who is depicted is not known for sure. The coin was introduced by Darius the Great of Persia some time between 522 and 486 BC and ended with Alexander the Great’s invasion in 330 BC. In ancient times, it was nicknamed “the archer”.

Alexander the Great had the Darius Archer coins melted down after the invasion to be replaced with his own coins.

The concept of minting coins was initially adopted by the Greek city states of Aegina, Corinth and Athens. This idea then rapidly spread across the Mediterranean. By the middle of the 6th century BC most mints had begun making coins with designs on both sides.

Hoards of coins are very important in dating coins. The British Museum had two very interesting coin hoards on display. The Corbridge gold coin hoard was discovered in 1911. These 160 gold coins were kept in a jug with 2 bronze coins wedged in the neck to conceal them. The jug was buried under the floor of a Roman house. The weight of the gold broke the bottom out of the jug when it was lifted, revealing the gold.

The Romans, who also used gold coins to pay their legions, emulated the practice of printing the emperor’s head on their aureus gold coins. They were usually 950 fine (22 carat) and weighed 7.3 grams (0.23 troy oz). Constantine introduced the solidus in 309, replacing the aureus as the standard gold coin of the Roman Empire. The solidus was a larger diameter and flatter coin, while the aureus was smaller, thicker and similar to the denarius.

In 1999, the British Museum acquired a group of over 400 gold coins, broken pieces of gold jewellery and ingots as well as pewter, pottery sherds and a merchant’s seal. This assemblage was recovered by a group of divers from the sea bed in Salcombe Bay in Devon. The coins were struck by the Sharifs of the Sa’dian dynasty, who ruled Morocco during the sixteenth and seventeeth centuries.

The 17th century assemblage contains the largest number (over 400) of Islamic gold coins ever found in the UK.

This has been a rather quick overview of ancient coinage. If you are interested in the subject, the British Museum has one of the best collections in the world, well worth a visit.

References:

White Gold, The Worlds Earliest Coins: http://www.imj.org.il/exhibitions/2012/WhiteGold/Introduction.html

Archaic and Classical Greek Coinage: http://www.academia.edu/1378165/Asia_Minor_to_the_Ionian_Revolt

Wildwinds: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/greece/ionia/uncertain/i.html

Refining Electrum: Ramage and Craddock 2000 pages 81-96

Spurlock Museum: http://www.spurlock.illinois.edu/search/details.php?a=1900.63.0646

Roman Coins Outside the Empire: http://www.academia.edu/370211/Roman_Gold_and_Hun_Kings_the_use_and_hoarding_of_solidi_in_the_late_fourth_and_fifth_centuries

1922 Guide to Coins and Medals British Museum: http://www.scribd.com/doc/46438420/COINS-MEDALS-BRITISH-MUSEUM

Vilmar: http://vilmarnumismatics.com/product/coins/