This is my second post on the Château de Vincennes, the first covered the history and grounds of the outer keep or Enciente. The Chateau de Vincennes was where both Philippe III and IV were married and three kings, namely Louis X, Philippe V and Charles IV, were born there. Henry V of England also passed away in the donjon tower in 1422 following the siege of Meaux. This really gave it a place in French history and made the Chateau more than just a hunting lodge and sometime home for kings. The Chateau boasts the tallest medieval fortified structure in not only France, but in all of Europe. It is a donjon tower that was added by Philip VI (1293-1350) in 1337. It was further fortified by the addition of a circuit of rectangular walls in the early 15th century. The Royal Keep which remains today and the fortified gate house were both completed in 1369 under the auspices of Charles V (1338-1380). The keep stands 160 feet high and is the only surviving medieval royal residence in France. Each side measures 50 feet and the walls are 10 feet thick. The château was built by Charles V in response to civil unrest during the Hundred Years War. The Hundred Years' War, a series of conflicts waged from 1337 to 1453, pitted the Kingdom of England against the Valois Capetians for control of the French throne. Each side drew many allies into the fighting.

At the top of the Châtelet's bell-tower, destroyed in 1837, Charles V had installed a mechanical clock in 1369. It had a large bell (currently kept in the Sainte-Chapelle) which called the faithful to the daily services. At that period, such devices were very expensive and very rare: in Paris, the first public mechanical clock was only installed in 1370 at the Palais de la Cité by the King himself. The reconstruction of the bell-tower made it possible to install a copy of Charles V's bell, which was inaugurated on 27 May 2000. The bell tower from 1369 housed the very first public clock in France and is on top of the gate house to the Royal Keep. The bell that can be seen today replaced the original bell in 2000. The original bell, seen above, can be seen the Chapel. The clock was located above the King’s study and on the same level as his bedroom. Be sure to climb to the top of the bell tower for some wonderful views of the Château and the surrounding country-side.

As the main entrance of the enceinte of the donjon, the facade of the Château was painstakingly decorated, something unusual which was to become widespread in military architecture. Under the window of the study, a carved cornice is used as a base for five niches, in which there are no statues at present. Above that window, a console once bore a statue which, according to a text, was the representation of the Trinity, placed above the King's place of work, like a sort of protection. We can't say which statues stood in the niches, but there was probably a representation of Saint Christopher on either side, as stated in a text from the period, a statue of the King and one of the Queen. Between the three central niches and the two side ones, there was a carved decoration destroyed in 1793, consisting of the French coat of arms with a dolphin underneath.

Just how serious the architects were about the security of the King can be seen in the path into the Royal Donjon or Keep. A separate moat surrounds the Royal Keep which can only be entered over narrow walkway with a drawbridge. Once inside the keep, you find two levels of defense along the walls, an enclosed upper walkway and a lower unenclosed area on the roofs of the small buildings for interior defense. The enclosure wall features a covered round-way, two corridors corbelled inwards and going around the Château, making it possible to do a whole round without interruption. Most of these interior buildings have been rebuilt over the years. Even the tower has undergone renovations from 2003-2006. To enter the tower, you need to climb enclosed stairs next to the entrance and enter on the second floor of the tower over a narrow walk bridge. If you continue up the stairs, you will find the reproductions of the first clock and bell installed in France. Interestingly, there are slits for archers but no particular openings for guns which were only being introduced in the Hundered Years War.

On the first floor, the central hall was probably a meeting room. The donjon was accessed through this floor. Against the vaults there is still oak panelling which, as detected through a careful look at the traces on the walls, used to cover the entire walls all the way down to the floor, as well as the vault and walls of a little oratory cut into the northern wall of the donjon. A dendrochronological study showed that this panelling was made from oak trees cut down a few years after 1363, most probably near the city of Gdansk (Poland).

The second floor and terrace of the tower of the Château are reached by a spiral staircase of great architectural interest. With its large diameter (3.32 m), it displays a few exceptional traits which were subsequently to become common: it is partly mounted on the outside of the building, in a sort of protruding tower; it is well lit over its entire height through four superimposed windows; moreover, it was covered by an eight-sided vault, destroyed in 1840.

The general layout of the second floor, which housed the King's bedroom, is fairly similar to that of the first floor. Major traces of the decoration at the time of Charles V in 1367 or 1368 still remain. The ribs of the vaults bear an embossed fleur-de-lis pattern coated with gold leaf against a blue background. A few hooks remaining in the vaults and traces on the walls show that the King's bedroom, just like the first-floor hall, was entirely wood-panelled, along with the small oratory cut into the northern wall of the donjon and the walls and vaults of the south-west turret.

A small room, perhaps 6 feet by 9 feet was the study of Henry V. An inventory of the royal collections made in 1380 gives precious indications on part of the furniture in the King's bedroom which boasted a large number of jewels. In the western window opening, in the light, hung a box which contained thirty one religious manuscripts, including two psalters who once belonged to Saint Louis. Starting in July 1367, the north-west turret, lit by a single window and fitted with a fireplace, was used to house the King's “coffers” i.e. his money. After that room, in the rectangular tower, a vestibule lit by a window gave access to a “study” on one side and to the latrines on the other. This study is a very small room with a fireplace and a vaulted ceiling whose ribs come down onto four carved consoles bearing the symbols of the Evangelists; the crown of the vault is decorated with a representation of the Trinity. In 1380, a large number of jewels, relics and manuscripts were kept there.

The private rooms of the King included a very small unheated chapel with a beautiful ceiling seen above.

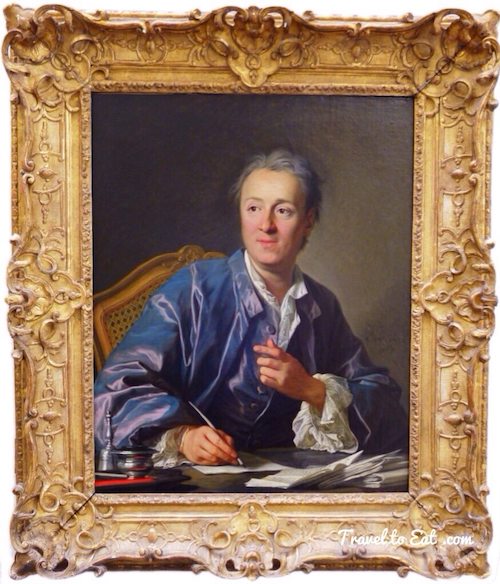

The ground floor, which was greatly modified in the 18th century, has a well and a big fireplace in its northern wall, which suggests a kitchen. However, for numerous reasons, this use is doubtful; as this floor is only accessible from the first floor, it would probably have been used as a store room and to house relatives or servants. Abandoned in the 18th century by Louis XIV, the château still served, first as the site of the Vincennes porcelain manufactory, the precursor to Sèvres, then as a state prison, which housed the marquis de Sade, Diderot, Mirabeau, and the famous confidence man, Jean Henri Latude, as well as a community of nuns of the English Benedictine Congregation from Cambrai. At the end of February 1791 a mob of more than a thousand workers from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, encouraged by members of the Cordeliers Club and led by Antoine Joseph Santerre, marched out to the Château, which, rumour had it, was being readied on the part of the Crown for political prisoners, and with crowbars and pickaxes set about demolishing it, as the Bastille had recently been demolished. The work was interrupted by the marquis de Lafayette who took several ringleaders prisoner, to the jeers of the Parisian workers.

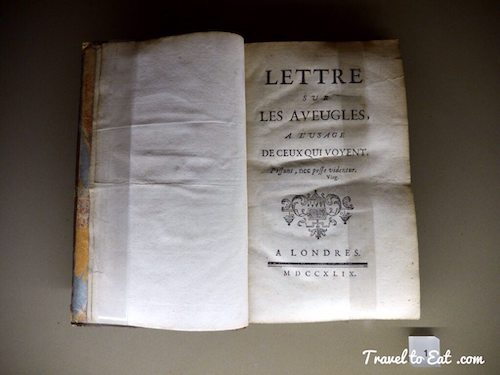

Diderot's celebrated Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient (“Letter on the Blind”) (1749), introduced him to the world as a daringly original thinker. The subject is a discussion of the interrelation between man's reason and the knowledge acquired through perception (the five senses). The title, “Letter on the Blind For the Use of Those Who See”, also evoked some ironic doubt about who exactly were “the blind” under discussion. In the essay a blind English mathematician named Saunderson argues that since knowledge derives from the senses, then mathematics is the only form of knowledge that both he and a sighted person can agree about. It is suggested that the blind could be taught to read through their sense of touch (a later essay, Lettre sur les sourds et muets, considered the case of a similar deprivation in the deaf and mute). What makes the Lettre sur les aveugles so remarkable, however, is its distinct, if undeveloped, presentation of the theory of variation and natural selection. Denis Diderot was imprisoned in the donjon of Vincennes in 1749 for three months for publishing these books and had to sign a pledge that there would be no further anti-religious books published during his lifetime.

[mappress mapid=”18″]

References:

Château Website: http://en.chateau-vincennes.fr/index.php

Diderot: http://www.iep.utm.edu/diderot/

Letter on the Blind: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=36470