We visited the British Museum during the Olympics and it was relatively quiet, probably most people were at the games. We were amazed that there was no entrance charge. The museum first opened to the public in 1759 in Montagu House in Bloomsbury, on the site of the current museum building. The original museum was the result of four collections, the physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane, the Cottonian Library, assembled by Sir Robert Cotton, the Harleian library of the Earls of Oxford and the Royal Library, assembled by various British monarchs. Together these four “foundation collections” included many of the most treasured books now in the British Library including the Lindisfarne Gospels and the sole surviving copy of Beowulf. The British Museum was the first of a new kind of museum – national, belonging to neither church nor king, freely open to the public and aiming to collect everything.

The donation in 1822 of the personal library of King George III’s set the stage for the museum’s expansion. Sir Robert Smirke was asked to draw up plans for an eastern extension to the museum for the reception of the Royal Library. The dilapidated Old Montagu House was demolished and work on the King’s Library Gallery began in 1823. The extension, the East Wing, was completed by 1831. In 1895 the trustees purchased the 69 houses surrounding the Museum with the intention of demolishing them and building around the West, North and East sides of the Museum. The first stage was the construction of the northern wing beginning in 1906. There was not enough money to put up more new buildings, and so the houses in the other streets are nearly all still standing.

The departure of the British Library to a new site at St Pancras, finally achieved in 1998, provided the space needed for the books. It also created the opportunity to redevelop the vacant space in Robert Smirke’s 19th-century central quadrangle into the Queen Elizabeth II Great Court – the largest covered square in Europe – which opened in 2000. Altogether the British Museum showcases on public display less than 1% of its entire collection, approximately 50,000 items. There are nearly one hundred galleries open to the public, representing 2 miles (3.2 km) of exhibition space, although the less popular ones have restricted opening times.

There is a restaurant on top of the central pillar, so if you are feeling hungry just go up the stairs instead of eating in one of the smaller cafes inside.

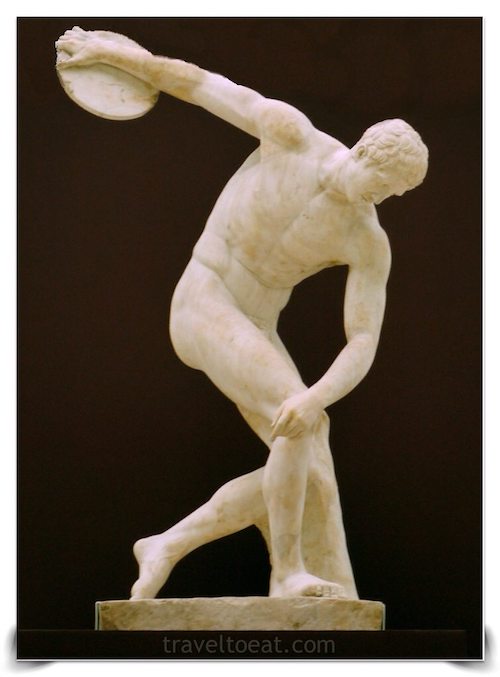

This marble statue is one of several copies of a lost bronze original of the fifth century BC which was attributed to the sculptor Myron (who lived about 470-440 BC). The head on this figure has been wrongly restored, and should be turned to look towards the discus. The popularity of the sculpture in antiquity was no doubt due to its representation of the athletic ideal. The Museum’s marble copy, known as the “Townley Discobolus”, was excavated at Hadrian’s Villa near Rome in 1791. This is one of the most famous images from the ancient world.

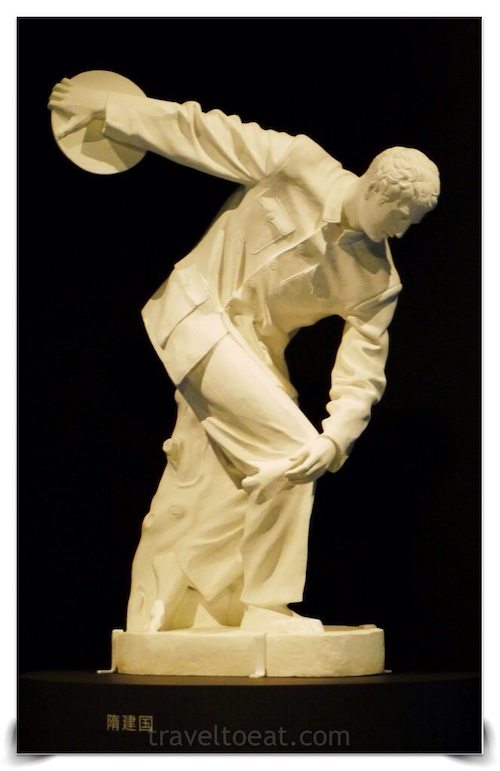

Sui Jianguo’s Discus Thrower was also on display. The Discobolus (discus thrower) is one of the most famous sculptures from the ancient world and has come to mean different things to different people. This display features contemporary Chinese artist Sui Jianguo’s beautiful and thought-provoking interpretation. Sui Jianguo is one of China’s most significant artists. As a sculptor, he has become internationally recognized for works that challenge the ideological assumptions and historical origins of Chinese Socialist Realism, the style in which he was trained. Sui’s sculpture is less an attack on official art than an infiltration of it. He likes to get under its skin, cloak it in ironies. This is expressed in this work as a tension between expression and repression, the Greek statue Discobulous poised to throw a discus while clad in constricting bureaucratic garb. Actually a pretty cool statue.

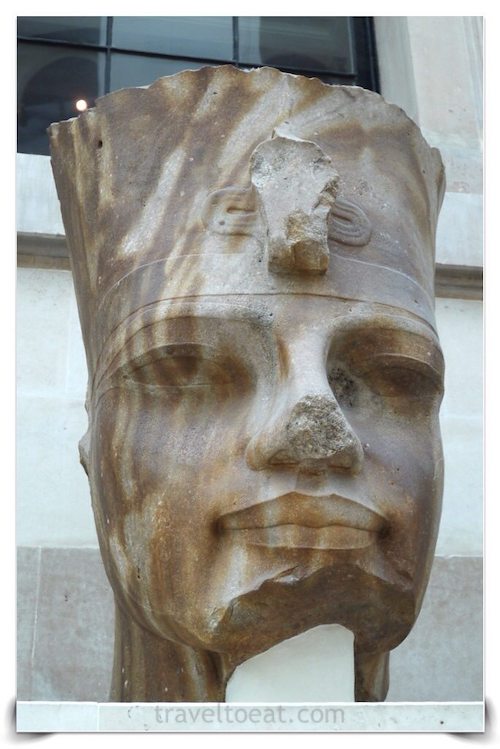

Also on display in the great court were a pair of massive quartzite heads of the Egyptian Pharoh Amenhoptep III which were found in the mortuary temple of the pharaoh Amenhotep III on the West Bank of the River Nile at Thebes (the present-day settlement of Kom el-Hitan) in Egypt. Only the heads of the two broken colossal statues have survived. When complete, the statues would have measured more than 26 feet (8 meters) high without their base.

I will stop here for the introduction, but I will have many more posts on what we saw at the British Museum including the next post on the Rosetta Stone.

References:

NYT: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/16/arts/16iht-rartsculptors16.html?pagewanted=all

The Sleep of Reason 2004: http://www.suijianguo.com/eng/htm/pinglun/p-2004-1.htm