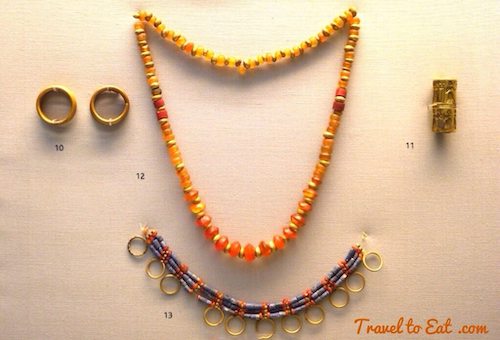

I have a few more images of the finds of Leonard Woolley at Ur from the British Museum. I thought I would include them in this post. Although the exact belief systems and practices behind the royal burials at Ur are not yet known to us, what is apparent is the high level of technical and artistic sophistication that produced the artifacts that they contain. The array of raw materials from which the objects are made all had to be imported into the resource-poor Mesopotamian floodplain, and their variety attests to the far-flung trading network of which Ur was a part. These materials include gold that must have come from Afghanistan, Iran, Anatolia, Egypt, or Nubia, and etched carnelian beads from the Indus Valley, as well as many stones that perhaps made their way primarily from eastern Iran. With few exceptions, however, these imported materials were worked into final form in southern Mesopotamia by craftsmen who created some of the most spectacular works of art preserved from ancient Sumer. All of these pieces are between 2500-2000 BC.

The 1920s and 1930s were archaeology’s heyday. In 1922, Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings gripped the public. The media of the day regularly reported on progress and finds at different excavation sites. Often colorfully described, these reports provided vivid pictures of life on excavations and fantastic glimpses of the culture, history, and lives of ancient peoples. The news stories about Ur were no different. Woolley’s eagerness to engage the general public and his unique ability to simplify and tell lively stories about his discoveries made him a popular figure. Woolley regularly contributed reports to the newspapers and The Illustrated London Newsabout the progress of his work at Ur. He never missed an opportunity to link what he found to Abraham and the Bible or to compare it to Egypt and Tutankhamen. The intense media coverage of Ur inspired readers, including European royalty such as Belgium’s King Albert, to see the excavations firsthand. The most intriguing guest was author Agatha Christie, who first visited in 1928. She became enthralled with life at the site, as well as good friends with Woolley’s wife, Katharine. She returned the following season and eventually married Woolley’s young archaeological field assistant, Max Mallowan. By 1927, Woolley had uncovered Ur’s ziggurat and the major public buildings around it. The only area left untouched was the site of Trial Trench A, where he had discovered burials back in 1922. Expanding this trench, Woolley excavated nearly 600 burials in three months. Over the next three seasons, he would uncover 1,100 more, including his most spectacular discoveries—the royal tombs—which included stone-built chambers, a wealth of artifacts made of gold, silver, and semi-precious stones, and evidence for the burial of court attendants alongside deceased kings and queens. In all, by 1934, he uncovered almost 2,000 burials.

References:

Abraham; Recent Discoveries and Hebrew Origins: http://books.google.com/books/about/Abraham.html?id=aNH7cQAACAAJ

The Sumerians: http://www.amazon.com/The-Sumerians-Norton-Library/dp/0393002926