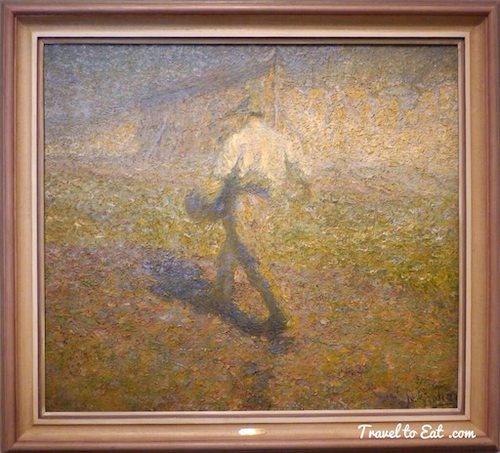

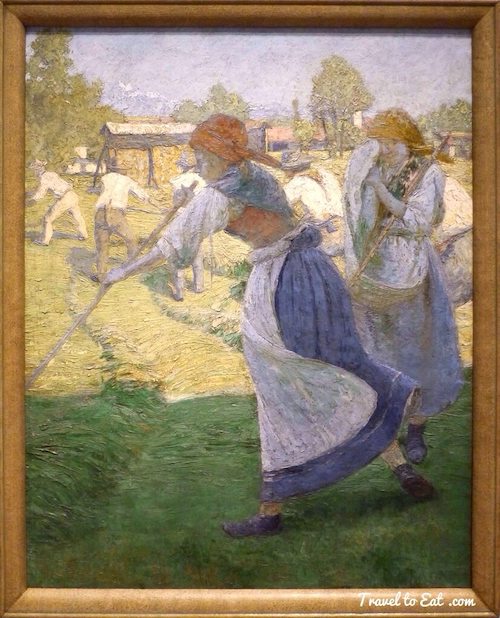

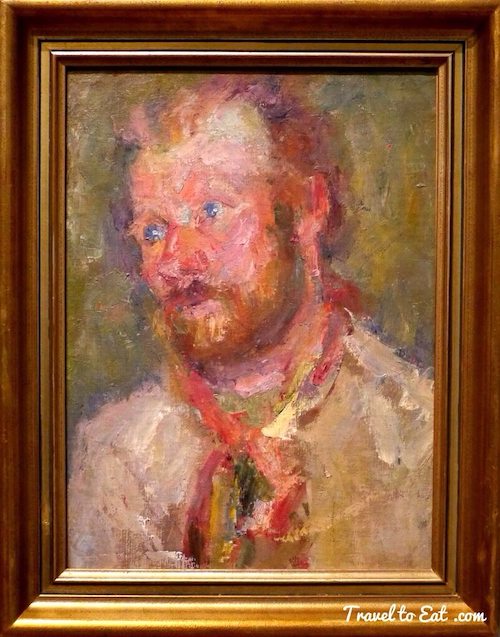

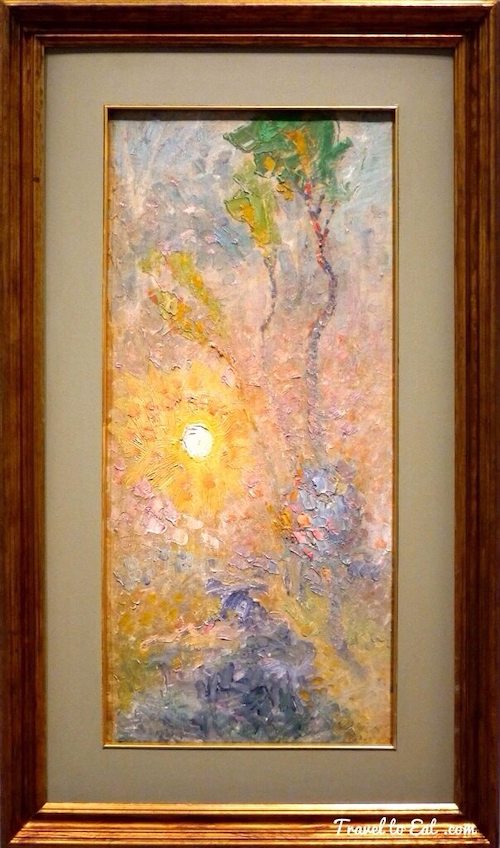

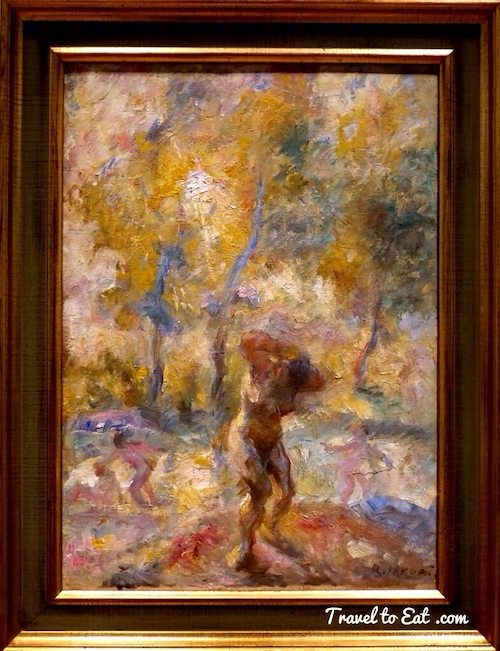

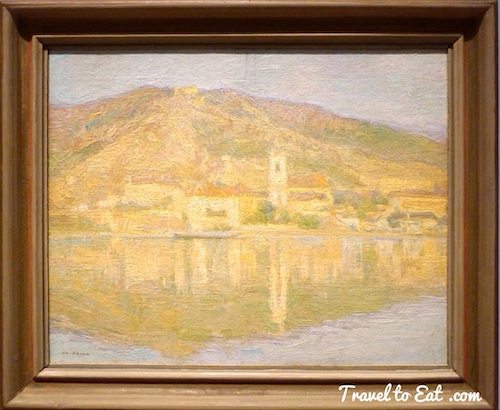

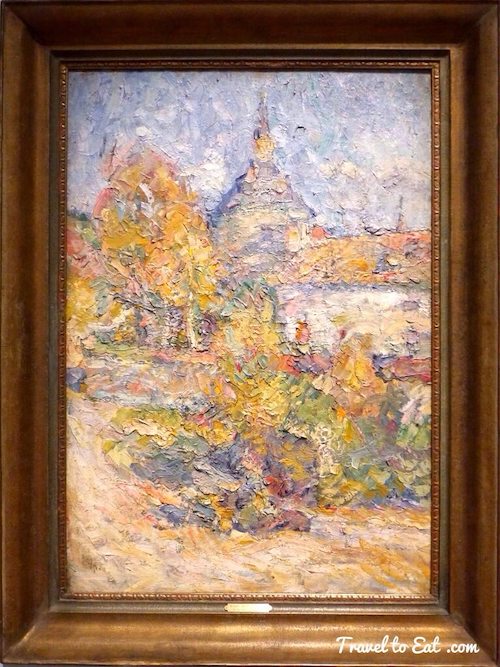

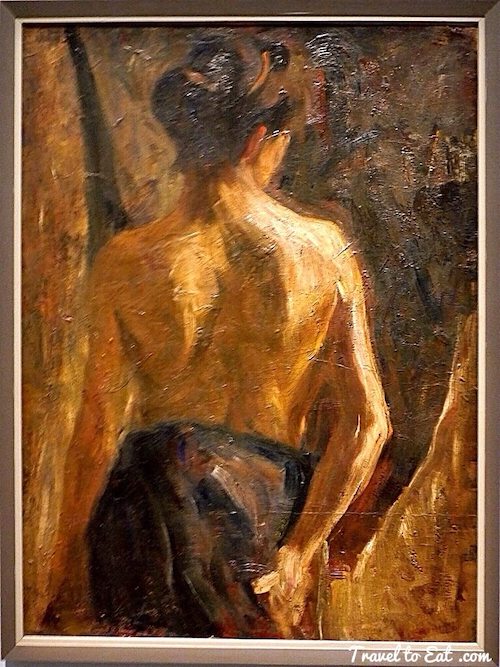

Last summer the Petit Palais hosted a retrospective exhibition of Slovenian Impressionists who were influenced by the French Impressionist movement which we were fortunate to visit. I thought it was a good subject to share. Their style, however, drew less on the original Impressionism born in France in 1860–1870 than on the form it was given by Monet in his Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral series, Van Gogh and his gestural Expressionism, and Giovanni Segantini, whose symbolism-inflected landscapes were a potent influence in this part of Europe. Their ambition was to transcend landscape painting’s anecdotal realism in favor of an emotional power some of them strove for in compositions verging on the abstract. Of the four, Ivan Grohar was the one closest to Symbolism in his spiritual conception of landscape. His Sower (seen above from 1907) was immediately taken up as the emblem of the emerging Slovenian nation. Matija Jama set out to capture the intense luminosity of tranquil landscapes, while Matej Sternen focused more on the human figure. Rihard Jakopič was the driving force behind the art scene in Ljubljana, where in 1909 he built, at his own expense, a pavilion that became an avant-garde exhibition venue. His bold, ardent paintings cover a wide range of themes, including spirited images of figures merging with the natural setting.

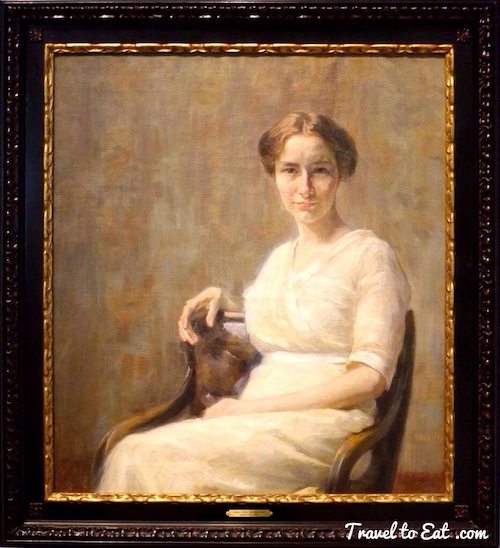

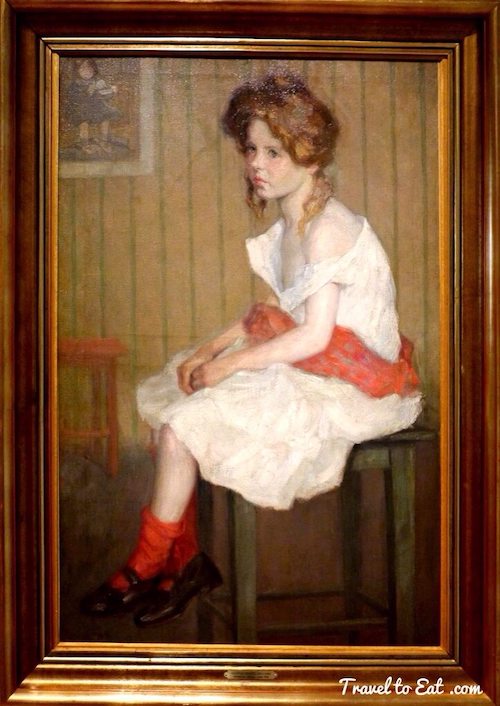

After studying in Munich with the painter Alois Erdtelt (it not being possible at the time for a woman to enter the official academy), Ivana Kobilca became the first Slovenian painter to be granted a solo exhibition in Ljubljana (1889). She stayed in Paris for two years, during which time she studied under Henri Gervex, painted in the Forest of Fontainebleau, and became a member of the Société Nazionale des Beaux-Arts, exhibiting her painting “Summer” in their 1891 salon and “The Children in the Grass” in 1892. In 1897 she and Ferro Vesel were the first Slovenian painters to be invited to the Venice Biennale, founded two years previously. She was a firmly established artist in 1903 when the mayor of Ljubljana, IvanHribar, commissioned a large allegorical painting. Her “Slovenia Paying Homageto Ljubljana” still hangs in the Municipal Council chamber of that city. She often used photography to work out the composition of her paintings. When they decided to seek a newer, more independent style, the Impressionist group was rebelling against the kind of official art that Kobilca represented.

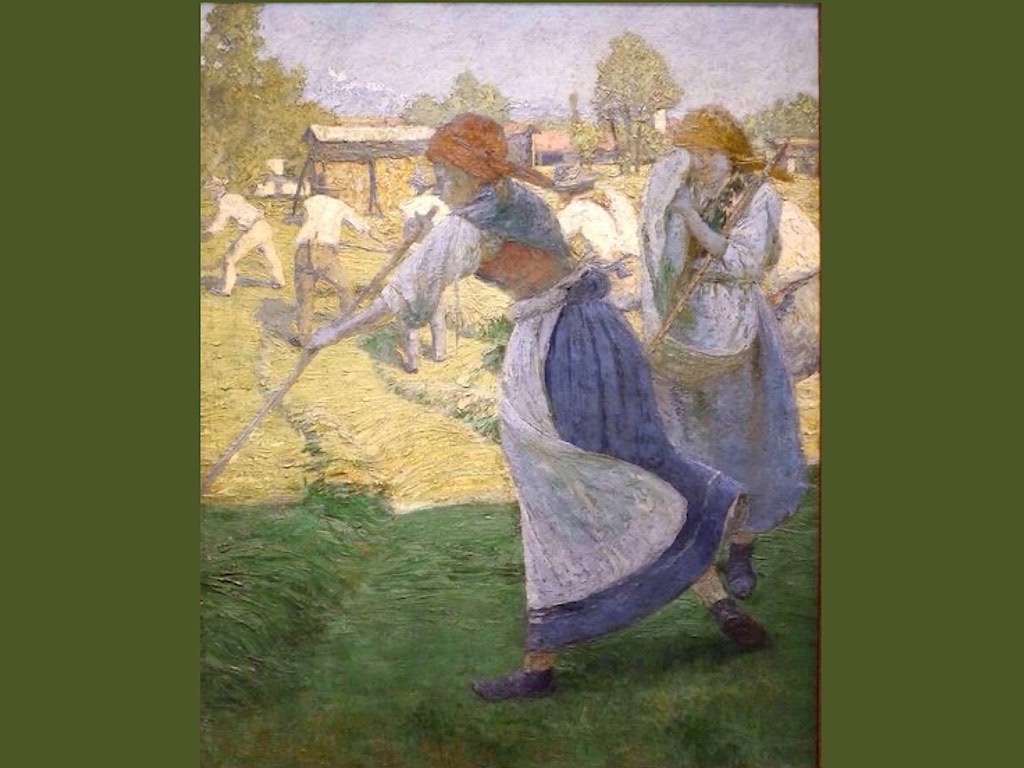

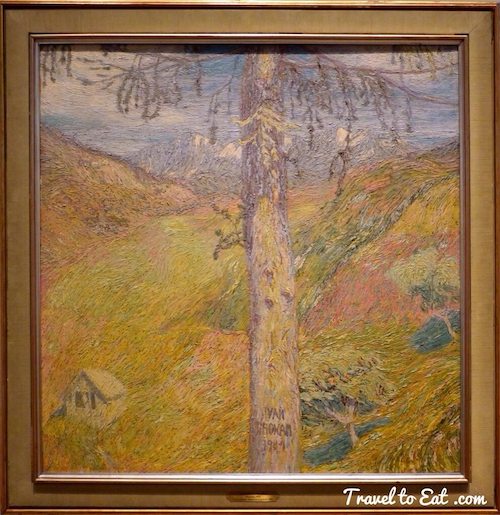

Ivan Grohar came from a modest, provincial background and first made a living executing religious paintings commissioned by the church. He completely changed direction when he went to Anton Aibes academy in Munich in 1898 and met the other painters of what was to become the Impressionist group. Grohar was already a confirmed practitioner of the newplain-air painting, when he exhibited “Haymakers” at the Society of Slovenian Artists second exhibition in Ljubljana in 1902. But his style of painting developed further, particularly under the influence of Italian painter Giovanni Segantini, who was highly acclaimed in that part of Europe. From then on, realism in his landscapes gave way to a more symbolist manner. In 1904 he joined Rihard Jakopič in Škofja Loka, where they painted several views of Kamnitnik Hill in very similar styles. In the same year, “Spring”, part of his contribution to the Sava club exhibition at the Miethke Gallery, Vienna, was looked on as a manifesto of young Slovenian painting. His painting “The Sower”, inspired by a photograph by Avgust Berthold, was shown in Trieste in 1907 and quickly became the symbol of the Slovenian nation.The evanescent quality of “The Shepherd”, painted towards the end of his short life, shows the extent to which Grohar’s painting was becoming more and more spiritual.

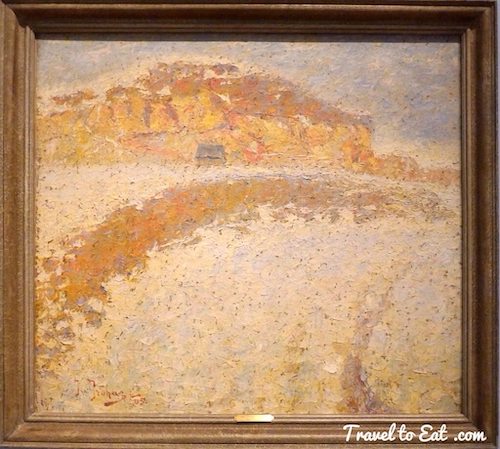

At the turn of the 20th century, Slovenia, then known as the Duchy of Carniola, was a state of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During this period, it opened up to modernism under the infuence of the Munich Secession (1892) and the Vienna Secession (1897). Carniolan artists and writers were moved by powerful nationalistic feelings, however, and sought to emphasize their individuality. A first generation of Realist painters which included Jurij Šubic and Ivana Kobilca, who both spent time in Paris, tended to look towards Western Europe, but they were succeeded by artists more concerned to make their name within the Slavonic areas of multi-ethnic Austria-Hungary. Ivan Grohar, Ricard Jopie, Matija Jana and Mateo Steven all met at the private academy in Munich, set up in 1891 by Slovenian painter Anton Abbe. They decided to concentrate on landscape painting as a reaction against the anecdotal, conventional paintings of the Realist generation.Their contribution to the second exhibition (1902) of the Society of Slovenian Artists was given a bad reception, but this only strengthened their determination to assert their originality. Up until 1906 they would meet fairly regularly in the small town of Škofja Loka, the “Barbizon” of Slovenian Impressionism. It lay to the north-west of Ljubljana and Rihard Jakopič, the strongest personality in the group, had moved there. They were joined by the photographer Avgust Berthold. The value of their work was eventually recognized in 1904 when, calling themselves the Save club, they held a group exhibition at the Miethke Gallery in Vienna. In addition to this Impressionist group, the Modern movement was an infuence on every area of creative activity in Ljubljana. In 1903, Gvidon Birolla, Maksim Gaspari, and Hinko Smrekar, who had all trained in Vienna, founded the Vesna group. They were principally illustrators, which brought them into contact with the foremost writers of their generation, Oton Župančič and Ivan Cankar. Within the group, Hinko Smrekar was particularly famous for his remarkable gifts as a caricaturist.

This was a really great exhibition and it shows that the Impressionist movement in France influenced not only American painters but also painters in Eastern Europe.

References:

Petit Palais Program: http://www.petitpalais.paris.fr/en/expositions/slovenian-impressionists-and-their-time-1890-1920