Benvenuto Cellini was one of the enigmatic, larger-than-life figures of the Italian Renaissance: a celebrated sculptor, goldsmith, author and soldier, but also a hooligan and even avenging killer. Much of Cellini's notoriety, and perhaps even fame, derives from his memoirs, begun in 1558 and abandoned in 1562, which were published posthumously under the title “The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini”. As noted by one biographer, “His amours and hatreds, his passions and delights, his love of the sumptuous and the exquisite in art, his self-applause and self-assertion, make this one of the most singular and fascinating books in existence.” He confessed to three murders and was several times imprisoned, in one instance breaking out of the Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome by climbing down a homemade rope of knotted bedsheets.

Perhaps one of Cellini's most famous works is the Cellini Salt Cellar (in Vienna called the Saliera – Italian for salt cellar), a partly-enameled gold table sculpture by Benvenuto Cellini. The Saliera is the only work of gold which can be attributed to Cellini with certainty and is sometimes referred to as the “Mona Lisa of Sculpture”. It was created in the style of the late Renaissance, the Mannerist period, and allegorically portrays “Terra e Mare” in Cellini's description in his Autobiography, allegorized as Neptune, god of the sea born by two sea horses, and Tellus (or Terra), Roman goddess of the earth, symbolizing their unity in producing salt mined from the earth. The legs of the two figures are intertwined, the way Cellini imagined the limbs of land and sea are conjoined. Tellus is perched on an elephant and surrounded by flowers and fruit that conceal small animals. Beside Tellus, is a miniature temple where peppercorns were to be stored while beside Neptune is a boat for holding salt supported by fish. Additional reclining figures, representing winds and the times of day, are carved into the base upon which the whole thing stands. The style of the School of Fontainebleau and Italian Mannerism is characterized by an elongation and abstraction of the poised rather than moving body, creating an unnatural elegance and sophistication.

The Saliera was initially offered as a wax model to Cardinal Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara who dismissed it due to its excessive price and infeasibility years earlier. It was finally created for Francis I of France, of Loire Valley and Fontainebleau fame, between 1540 and 1543. From his descendant Charles IX it passed to Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol as a gift, who had acted as a proxy for Charles in his wedding to Elizabeth. Rather than casting the sculpture, it was sculpted by hand from rolled gold into its delicate shape. It measures about 10 inches tall. The base is made of ebony, about 13 inches wide and features ivory bearings to roll it around in order to appreciate it better. When Francis I moved it around the table, he was fuguratively moving the world. It remains, to this day, one of the most striking and celebrated works of Mannerist design, in fact, the very emblem of that era's excesses. According to Cellini, when it was presented to Francis I, the king “gasped in amazement and could not take his eyes off it.”

In 2003 Robert Mang, a 50-year-old specialist in security-alarm systems pulled off one of the biggest art heists in recent history: the removal of the “Saliera” from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. After holding the Cellini masterpiece, valued at roughly $60 million, for nearly three years and making two attempts to collect about $12 million in ransom, Mr. Mang was identified as the culprit in 2006 after the police had circulated security camera images of him buying a cellphone that he used to send a text message. He led the police to a wooded area about 50 miles northeast of Vienna where he had buried the legendary 10 inch-high sculpture inside a lead box. The Saliera was unharmed.

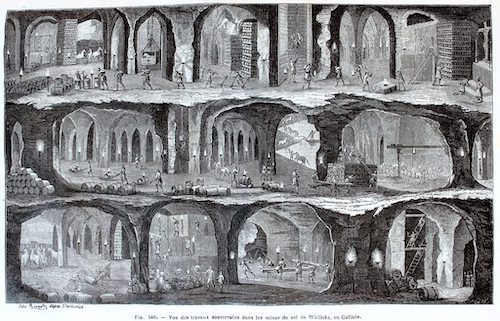

It is ironic that the Saliera ended up with the Habsburgs in Vienna. Salt has often been considered so valuable that it served as currency, and it is still exchanged as such in places today. Salt was a good reliable source of income, sometimes called “white gold” in medieval times. The Habsburgs were in the salt business, they created a monopoly in salt in Europe for themselves and tried to squeeze out their few competitors. The Habsburgs were also good at exploiting the salt deposits to be found in their territories, with the result that the salt industry became one of their most important sources of income. In order to make sure that they kept this income for themselves, they established a monopoly in the production of salt at the end of the fifteenth century and later demonstratively extended this to the whole salt trade. Revenue from the salt monopoly went up continuously as a result of rising demand and price increases. At the beginning of the eighteenth century it was some 1.7 million Gulden per year that flowed into the Habsburg coffers, while barely sixty years later it was just under nine million Gulden (a lot of money in any currency). The Gulden was the currency of the lands of the House of Habsburg between 1754 and 1892.

Sadly, few works by Cellini survive today. The second Florentine duke, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, commissioned Perseus with the head of Medusa with specific political connections to the other sculptural works in the Perseus with the head of Medusa by Benvento Cellini 1545 in Loggia dei Lanzi of the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, Italy. When the piece was revealed to the public on 27 April 1554, Michelangelo’s David, Bandinelli’s Hercules and Cacus, and Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes were already erected in the piazza. The bronze sculpture and the legend that Medusa’s head turns men to stone is appropriately surrounded by three huge marble statues of men: Hercules, David and later Neptune. By 1996, centuries of environmental pollution exposure had streaked and banded the statue. In December 1996 it was removed from the Loggia and transferred to the Uffizi for cleaning and restoration. It was a slow, years-long process, and the restored statue was not returned to its home until June 2000.

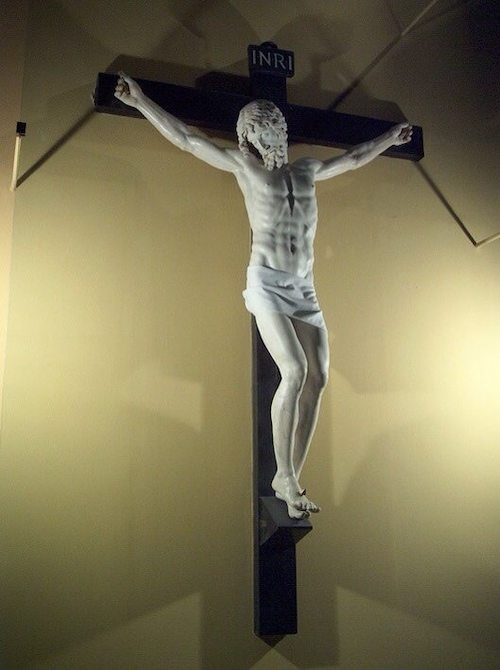

One of the most important works by Cellini from late in his career was a life-size nude crucifix carved from marble. Although originally intended to be placed over his tomb, this crucifix was sold to the Medici family who gave it to Spain. Today the crucifix is in the Escorial Monastery near Madrid, where it has usually been displayed in an altered form, the monastery added a loincloth and a crown of thorns.

There are a few scattered medals, coins and medallions but these are essentially the legacy of the famous Benvenuto Cellini. I have to say, to see the Saliera in person was thrilling, if you are in Vienna you should see it too.

References:

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4028

The Salt Cellar of Cellini: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2003/05/cellinis_stellar_cellar.html

NY Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/26/arts/design/26cell.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&

James Greer: http://fictionaut.com/stories/james-greer/cellinis-salt-cellar

Commissioning the Saliera: http://idlespeculations-terryprest.blogspot.com/2006/12/cellini-pinch-of-salt.html

Salt and the Habsburgs: http://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/white-gold-habsburgs-salt-monopoly

Mark Kurlansky, History of Salt: http://www.amazon.com/Salt-World-History-Mark-Kurlansky/dp/0142001619

López Gajate, Juan. El Cristo Blanco de Cellini. San Lorenzo del Escorial: Escurialenses, 1995.