Normandy is a region of France with historical ties to the Gauls, Romans, Vikings and England. Belgian and Celts, known as Gauls, invaded Normandy in successive waves from the 4th century BC to the 3rd century BC. Much of our knowledge about this group comes from Julius Caesar’s de Bello Gallico. Under the reorganization of the empire by Diocletian, Rouen became the chief city of the divided province of Gallia Lugdunensis II and reached the apogee of its Roman development, with an amphitheatre and thermae of which the foundations remain. In 57 BC the Gauls united under Vercingetorix in an attempt to resist the onslaught of Caesar’s army. After their defeat at Alesia, the people of Normandy continued to fight until 51 BC, the year Caesar completed his conquest of Gaul.

The technique of half-timbering came from this period in Celtic huts. As shown above from a building in Rouen, they would first frame the house with the best timber and then use odd lengths to fill in. This created a lattice of panels which were then filled with a non-loadbearing material or “nogging” of brick, clay or plaster, the frame was often exposed on the outside of the building. This is essentially the same system we use today and these houses can be seen throughout England and Normandy.

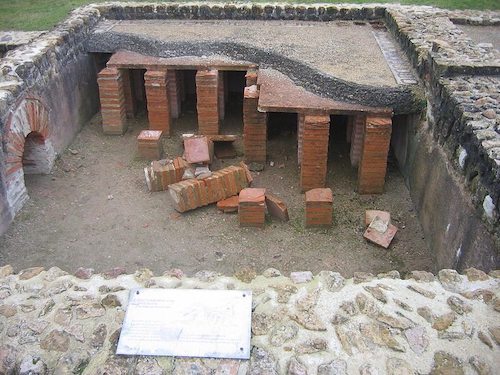

Roman villas and baths were built and heated by means of the Roman hypocaust, a false floor was created, supported by pillars and hot air was forced from a furnace (see picture at right) beneath the floor and up terra cotta pipes in the walls, thus providing central heating for the building. This was expensive to maintain and required lots of fuel. Central heating was not seen again in Europe for almost two millennia.

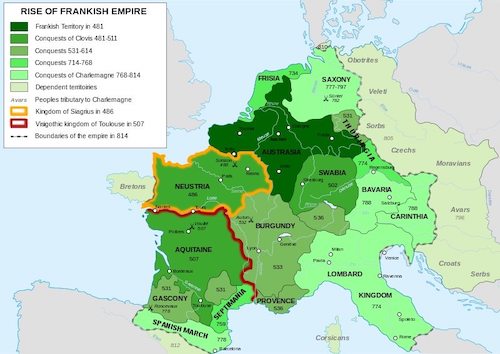

In the late 3rd century, barbarian raids devastated Normandy. Traces of fire and hastily buried treasures bear evidence to the degree of insecurity in Northern Gaul due to Saxon pirates. By 451 the Roman Empire was on the verge of collapsing. Aquitania (southern France) was definitely abandoned to the Visigoths, who would soon conquer a significant part of southern Gaul as well as most of the Iberian Peninsula. The Burgundians claimed their own kingdom, and northern Gaul was practically abandoned to the Franks under Childeric (457-481), the founder of the Merovingian dynasty. Under Clovis (481-511) his son, the boundaries of the Frankish empire were significantly enlarged and Clovis made Paris his capital. Under Frankish inheritance traditions, all sons would inherit part of the land, so four Frankish kingdoms emerged on the death of Clovis: centered on Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims. Over time, the borders and numbers of Frankish kingdoms were fluid and changed frequently.

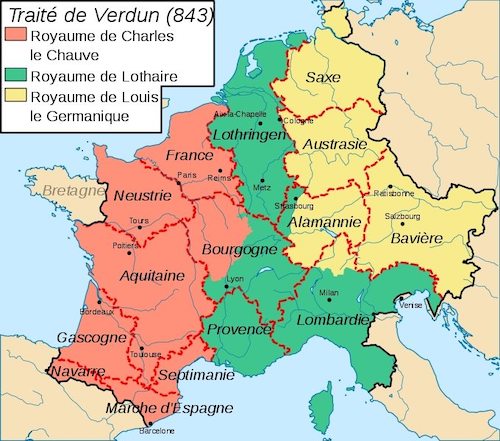

The assumption of the crown in 751 by Pepin the Short (son of Charles Martel) established the Carolingian dynasty and consolidated power as the Kings of the Franks. His son Charlemagne (742-814) basically conquered all of modern day Europe and was crowned “Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in the West” in 800 by Pope Leo III. The Treaty of Verdun in 843 was a treaty between the three surviving sons of Louis the Pious, the son and successor of Charlemagne, which divided the Carolingian Empire into three kingdoms. Charles the bald got France, Louis the German got Germany and Lothair got the middle.

The division reflected an adherence to the old Frankish custom of partible or divisible inheritance amongst a ruler’s sons, rather than inheritance by the eldest son, which would soon be adopted by both Frankish kingdoms. Since the Middle Frankish Kingdom combined lengthy and vulnerable land borders with poor internal communications as it was severed by the Alps, it was not a viable entity and soon fragmented. Generations of kings of France and Germany were unable to establish a firm rule over Lothair’s kingdom as were two World Wars in recent times. I covered this in the “Travel to Eat” website from the viewpoint of Provance.

Under the Carolingians, the French kingdom was ravaged by Viking raiders. An expedition in 845 went up the Seine and reached Paris. Led by Rollo (846-941) some Vikings had settled in Normandy and were granted the land, first as counts and then as dukes, by King Charles the Simple in 911 in order to protect the land from other raiders. The people that emerged from the interactions between the new Viking aristocracy and the already mixed Franks and Gallo-Romans became known as the Normans. The Normans quickly adapted to the indigenous culture, renouncing paganism and converting to Christianity. They adopted the language of their new home and added features from their own Norse language, transforming it into the Norman language. They further blended into the culture by intermarrying with the local population.

The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, under which Charles gave Rouen and the area of present-day Upper Normandy (Haute Normandie in the map below) to Rollo, established the Duchy of Normandy. In exchange Rollo pledged vassalage to Charles and agreed to be baptized. Rollo vowed to guard the estuaries of the Seine from further Viking attacks. When he died in 941 he was buried in Notre Dame Rouen. With a series of conquests, the territory of Normandy gradually expanded toward Brittainy. The Scandinavian colonisation was principally Danish, with a Norwegian element in the south.

Norman expansion was actively encouraged by the French kings as long as it was directed against Brittany, because this kept the Breton kings under control and weakened the power of the Normans while allowing them an outlet for adventure. In 933 William Longsword (son of Rollo and also buried in Notre Dame Rouen) annexed the Cotentin and the islands, described as “the land of the Bretons by the seacoast” (lower Normandy or Basse Normandie in the map above) from the Bretons who were otherwise engaged with other Viking bands. This transfer of power was recognised by the French king.

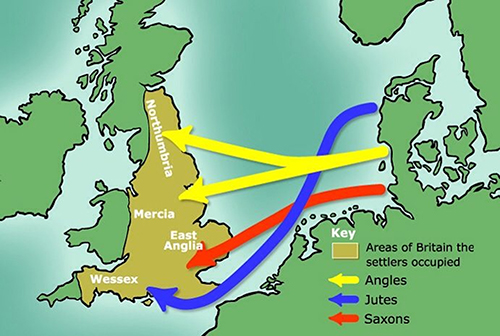

The Benedictine monk Bede, writing in the early 8th century, identified the English as the descendants of three Germanic tribes; the Angles from northern Germany, the Saxons from Lower Saxony and Jutes from Denmark. According to tradition, the Saxons (and other tribes) first entered Britain en masse in the 5th century as part of a deal to protect the Britons from the incursions of the Picts, Gaels, and others.

From around 800, waves of Danish assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles were gradually followed by a succession of Danish settlers. Danish raiders first began to settle in England in 865 starting in Northumbria. By 878 the Danes had become established in a large area known as the Danelaw seen above. Their expansion was stopped by the first “King of the Anglo-Saxons”, King of Wessex, Alfred the great (849-899). This the same time period as the establishment of Normandy. The reasons for the waves of immigration were complex and bound to the political situation in Scandinavia at that time; moreover, they occurred when Viking settlers were also establishing their presence in the Hebrides, Orkney, the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, France (Normandy), Russia and Ukraine. The Danes were ejected from England in 954 by Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the great.

The Danes never gave up their designs on England. From 1016 to 1035 Cnut the Great ruled over a unified English kingdom, itself the product of a hitherto resurgent Wessex, as part of his North Sea Empire, together with Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden. Cnut was succeeded in England by Harold Harefoot (1035-1040), Harthacut for 2 years and by Edward the Confessor (1042-1066).

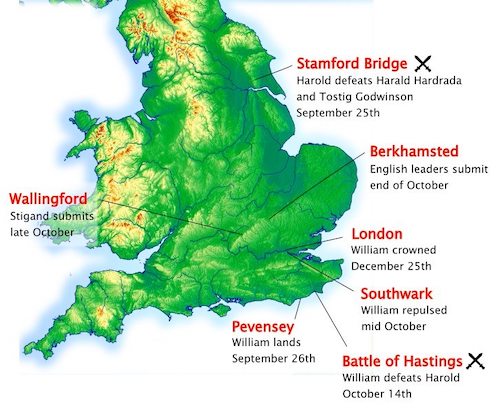

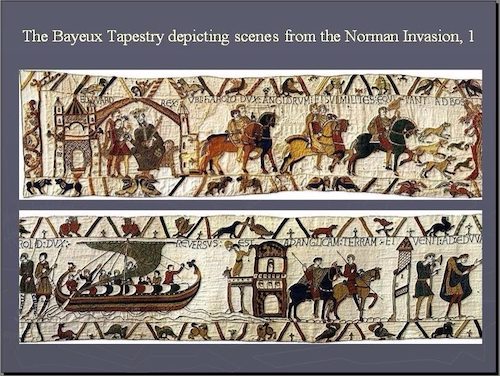

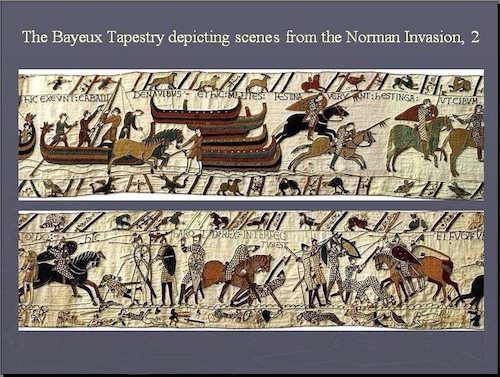

Edward died in January 1066 without an obvious successor, and an English nobleman, Harold Godwinson, took the throne. In the autumn of that same year, two rival claimants to the throne led invasions of England in short succession. First, Harald Hardrada of Norway took York in September, but was defeated by Harold at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, in Yorkshire. Then, three weeks later, William of Normandy (William the Conquerer) defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings, in Sussex, and in December he accepted the submission of Edgar the Ætheling, last in the line of Anglo-Saxon kings, at Berkhamsted. William the conquerer was crowned King of England December 25, 1066, reigning until his death in 1087.

He invaded Scotland in 1072 and concluded a truce. He marched on Wales in 1081 and established defensive buffer counties. He spent the last months of his reign fighting Phillip I of France. His reign in England was marked by the construction of castles, the settling of a new Norman nobility on the land, and change in the composition of the English clergy. By William’s death in 1087, after weathering a series of rebellions, most of the native Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had been replaced by Norman and other continental magnates. He did not try to integrate his various domains into one empire, but instead continued to administer each part separately. William’s lands were divided after his death: Normandy went to his eldest son, Robert, and his second surviving son, William, received England. He was buried in Caen, Normandy.

In 1204, during the reign of England’s King John, mainland Normandy was taken from England by France under Philip II of France. The Channel Islands remained under English control. In 1259, Henry III of England recognised the legality of French possession of mainland Normandy under the Treaty of Paris. His successors, however, often fought to regain control of mainland French Normandy.

The Charte aux Normands granted by Louis X of France in 1315 (and later re-confirmed in 1339) – like the analogous Magna Carta granted in England in the aftermath of 1204 – guaranteed the liberties and privileges of the province of Normandy.

When many Norman towns (Alençon, Rouen, Caen, Coutances, Bayeux) joined the Protestant Reformation during the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), battles ensued throughout the province and many left.

Samuel de Champlain left the port of Honfleur in 1604 and founded Acadia. Four years later, he founded Quebec City. From that point onwards, the Normans engaged in a policy of expansion in North America. They continued the exploration of the New World: René Robert Cavelier de La Salle travelled in the area of the Great Lakes, then on the Mississippi River. Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his brother Lemoyne de Bienville founded Louisiana, Biloxi, Mobile and New Orleans. Territories located between Quebec and the Mississippi Delta were opened up to establish Canada and Louisiana. Colonists from Normandy were among the most active in New France, comprising Acadia, Canada, and Louisiana.

Well this has been a long post, but I hope it will give you special insight into the uniqueness of Normandy and it’s special relationship with England, America and the Vikings.