The Wallace Collection is a national museum in London which displays the works of art collected in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by the first four Marquesses of Hertford and Sir Richard Wallace, the son of the 4th Marquess. It was bequeathed to the British nation by Sir Richard's widow, Lady Wallace, in 1897. I have written a background post on the union of the Seymour and Conway families which can be found here. This post explores the life of the first four Marquess of Hertford and the life of Sir Richard Wallace.

The interior is pretty remarkable, unlike other museums in which the museum housing the collection was separate from the collection, this was actually the home of the Marquess of Hertford. The history of this family is really intertwined in the history of England and the British monarchy. Even though the British royal family is not specifically Seymour or Conway, these families functioned in the second tier of the nobility, by marriage and their wits managed to influence the history of Great Britain and accumulate one of the most far-flung and influential fortunes of Europe. In addition they managed to spend all the money and influence on an illegitimate final progeny and to create one of the great art collections of the world.

To understand this story, you need to know the players and their genealogy. Francis Seymour-Conway (1719-94) was created 1st Marquess of Hertford in 1793, the year before he died. He was descended from the Edward Seymour who became the discredited Lord Protector of England in 1547. His family’s property included Ragley Hall in Warwickshire (still the country seat of the Marquesses of Hertford), Conway Castle, Sudbourne Hall in Suffolk and extensive estates in Ireland. He was the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1765-1766. One look at his portrait tells what you need to know, the English would describe him as a hard-bitten man, someone who is connected, rich and knows it. That patch on his jacket is a measure of just how connected he was, it is the insignia of the Knight of the Order of the Garter granted to him in 1756.

The Most Noble Order of the Garter, founded in 1348 by King Edward III, is the highest order of chivalry existing in England and is dedicated to the image and arms of St. George as England's patron saint. Membership in the order is limited to the Sovereign, the Prince of Wales, and no more than twenty-four members, knights, or Companions. The theoretical distinction between a marquess and other titles has, since the Middle Ages, faded into obscurity. In times past, the distinction between a count and a marquess was that a marquess's land, called a march, was on the border of the country, while a count's land, called a county, often wasn't. Because of this, a marquess was trusted to defend and fortify against potentially hostile neighbors and was thus more important and ranked higher than a count. The title is ranked below duke, which was often restricted to the royal family and those that were held in high enough esteem to be granted such a title. The word “marquess” is unusual in English, ending in “-ess” but referring to a male and not a female. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above viscount.

Francis Ingram-Seymour-Conway, 2nd Marquess of Hertford held seats in the parliaments of both Ireland and Great Britain, and served as Chief Secretary for Ireland under his father. He subsequently held positions in the Royal Household, including serving as Lord Chamberlain between 1812 and 1822. He married, as a second wife, Isabella Anne Ingram, daughter of Charles Ingram, 9th Viscount of Irvine. She was a mistress of George IV, apparently at the same time. On the death of his mother-in-law in 1807, he and his wife added the surname Ingram to their own, due to the fortune they received. As a result of this marriage, substantial additional funds were accumulated. In 1807 he was appointed a Knight of the Garter. Lord Hertford died in London in June 1822, aged 79, and was succeeded by his son from his second marriage, Francis. His wife died in 1836.

Their son was Francis Charles Seymour-Conway, 3rd Marquess of Hertford. Lord Hertford was a considerable art collector, as were his son and grandson, many of his pictures are in the Wallace Collection which they founded. He sat as Member of Parliament for Orford from 1797 to 1802, for Lisburn from 1802 to 1812, for Antrim from 1812 to 1818 and for Camelford from 1820 to 1822. In March 1812 he was sworn into the Privy Council. In 1822 he was made a Knight of the Garter. He married Maria Emilia Fagnani in 1798 whose father was either William Douglas, 4th Duke of Queensberry or George Augustus Selwyn, both of whom left her left her very large legacies. No one really knows who her father was but “the Marchesa,” who had been a ballet dancer, kept the secret of the past securely. When Selwyn died in 1801 he left £33,000 Maria, and the rest to Queensberry. Then when Queensberry died in 1810, Maria had her bank account increased again by still another £350,000, as well as his famous house opposite the Green Park in Piccadilly. After four years of marriage they were estranged, and she lived in Paris for the rest of her life. Lord Hertford was the prototype for the characters of the Marquess of Monmouth in Benjamin Disraeli's 1844 novel, Coningsby and the Marquess of Steyne in William Makepeace Thackeray's 1848 novel, Vanity Fair. In his last years he was said to live with a retinue of prostitutes. When the third Marquess of Hertford died in London in 1842 he was credited with the possession of nearly £2,000,000.

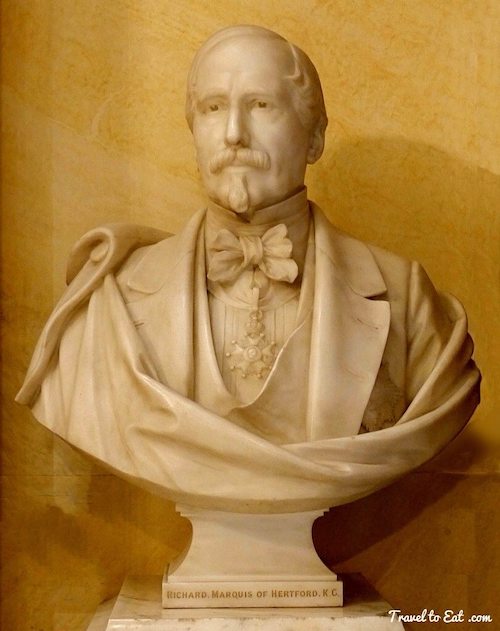

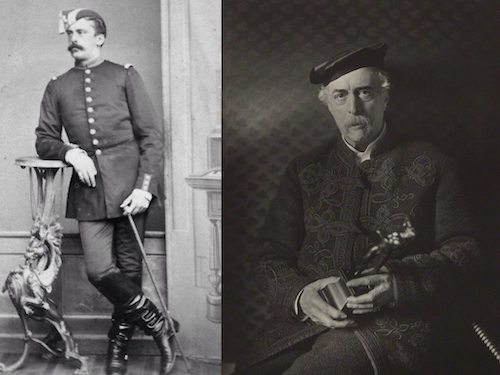

Richard Seymour-Conway (1800-70), the 4th Marquess, was brought up in Paris by his mother, Maria Emilia Fagnani, and came to England in 1816. He was briefly an MP and a cavalry officer, but by 1829, when he bought a large apartment at number 2 rue Laffitte, he had determined to forgo any public duties and to settle in Paris. This fourth Marquess of Hertford, although he possessed four palatial mansions in London, besides Rugley, Sudbourne, and other places, made his home in Paris. In 1835 he also bought the Château Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne. The 4th Marquess never married and was regarded as a very cranky, eccentric bachelor. Witty and intelligent as well as one of the richest men in Europe, he sometimes ventured into Parisian society and became friendly with Napoleon III. But there was a neurotic side to his personality and he preferred a reclusive life. In addition to the wealth of his mother and father the Irish estate at Lisburn County Antrim, was rolling in up to £75,000 a year. He only knew Lisburn by name and by his bank-book, and only visited once as MP for County Antrim for his four year term (1822-6).

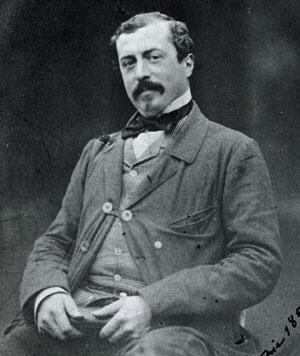

Richard Jackson (1818-90) was the illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess of Hertford and Mrs Agnes Jackson. She was a kind of “fille du regiment” of the 10th Hussars, and young Seymour-Conway made a home for her in Paris. There Wallace was born, and when they parted company, Jackson the child was placed with a concierge in the Rue de Clichy. There he ran wild until he was six years old. Lady Hertford (Maria Fagniani) was persuaded to adopt him, much against the inclination, at first, of her son. The 4th Marquess never acknowledged his paternity, and in 1842 Wallace took his mother's maiden name. Until his father's death he acted as the 4th Marquess's sale-room assistant and adviser. It is one redeeming trait that, if the Marquess was cold and harsh to his tenantry in Ireland, he showed much kindly affection to Wallace, who reciprocated the feeling. He died in 1870.

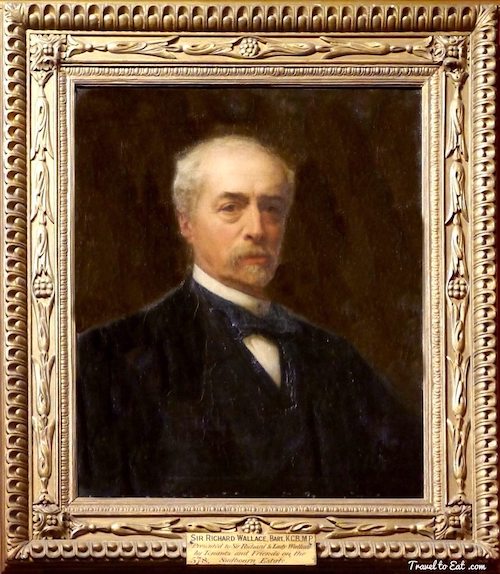

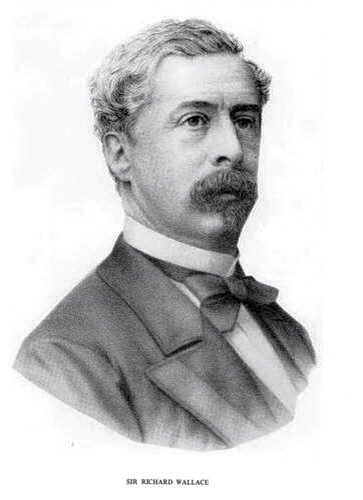

After the funeral in Paris on that August afternoon in 1870, the reading of the will was the occasion of astonishment. The title and entailed estates passed to the elder son of the deceased Marquess's cousin, Sir George Seymour. In addition however, “To reward as much as I can Richard Wallace for all his care and attention to my dear mother, and likewise for his devotedness to me during a long and painful illness I had in Paris in 1840, and on all other occasions, I give all my unentailed property to the said Richard Wallace, now living at the Hotel des Bains, Boulogne.” That “unentailed property” comprised not just the priceless collection of art, but the houses in Paris, Bagatelle and No. 2 Rue Lafitte and the big estates in Lisburn. Richard Wallace was utterly unaware of his great fortune until that afternoon of the funeral. He soon also bought the lease of Hertford House from the 5th Marquess of Hertford where the collection is now housed. While Paris was besieged by the Prussians and then devastated by the uprising of the Commune, Wallace won a considerable reputation through charitable works and gifts to humanitarian causes. In recognition of his philanthropy he was made a baronet in 1871, just after he had married his mistress, Julie Castelnau, the mother of his 24 year old son, Edmond Richard. Wallace was created baronet in 1871 and was Member of Parliament for Lisburn from 1873 to 1885.

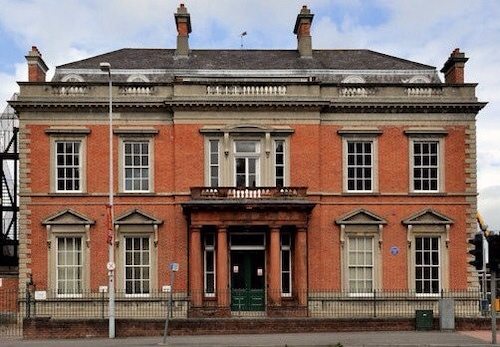

The reign of terror and oppression so long imposed on the estate in Ireland was at once changed. Dean Stannus, the old agent, was replaced by another, and tar-barrels burnt in rejoicing. The tenants had encouragement to buy out their farms and holdings, and instead of the bad old “fines” system they had the privilege of twenty years' purchase, even though others were willing to agree to the more extended twenty-five years. The progress of Lisburn was advanced by grants of sites in fee simple, so that the towns valuation, which was only £15,339 in 1874, became £23,650 in 1893. He built a residence for himself opposite the Castle Gardens, and it is now utilised as a splendid technical institute. Then in 1884 he gave Lisburn its handsome Wallace Park of twenty-five acres, and the year previously built the handsome Courthouse, with its Corinthian pillars, beside the railway station. He also gave the town five of his famous water fountains.

Julie-Amélie-Charlotte Castelnau (1819-97), married Richard Wallace in 1871, having been his mistress for many years. She is said to have been an assistant in a perfumer’s shop when they met. In 1890 Sir Richard Wallace bequeathed to her all his property. There is no evidence that she had any enthusiasm for the great collection for which she then became responsible and, after Wallace’s death, she led a secluded life at Hertford House.It was almost certainly the loyal desire to fulfill her husband’s wishes that led her to leave the collection at Hertford House to England on her death.

The Paris Siege and then the Commune, which shocked and disgusted the finer instincts of Wallace, settled one thing for him. For the second time in his lifetime the Collection had been in danger through revolution in Paris. He would move it to London and with it himself. Further, when the elections for French Chamber of Deputies were about to take place Wallace expressed a wish to be considered for election. He thought he was entitled to such an honour in view of his work during the Siege. On a technicality that he was not a Frenchman, he was debarred. This made him determined to move to Britain and live there.

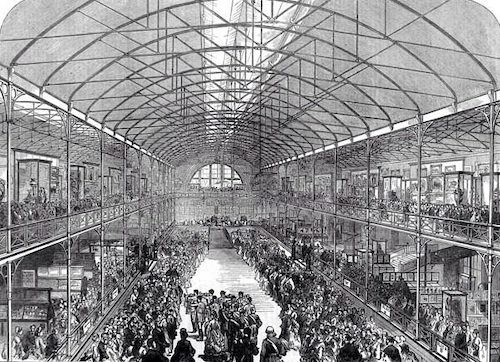

Wallace agreed, that his Collection should be shown in the newly erected museum at Bethnal Green so it was quietly transferred from Paris for this purpose. Something like 25 train wagons were needed to convey the precious works – though not all at once. In all 736 pictures, 227 miniatures, 446 pieces of furniture, sculpture and decorative bronzes, 240 porcelain objects, 141 pieces of majolica and 200 items of jewellery were moved from Paris to Bethnal Green without any suspicions on the part of the Parisians. The Exhibition is also notable for the start of the close friendship between Wallace and the Prince and Princess of Wales with whom he was a great favourite. The Prince opened the Exhibition in 1872 and was taken on a tour of it by Wallace, who was accompanied by Lady Wallace and their son Edmond. It was an outstanding success.

He now had everything he wanted and should have been a contented man. In the short space of two years he had risen from comparative obscurity as a private secretary to become one of the most famous men in the Kingdom, a landed proprietor beloved by his tenants, a Member of Parliament and the owner of the finest private art collection in the world. However there were problems. First there was Lady Wallace. She was unhappy in England and made everyone around her unhappy, too. She did not like London, its society and English life generally and she preferred the life she had led for so many years in Paris. Edmond Wallace was 24 when his parents married. In France this rendered him legitimate; in England it did not. After the war he resigned his commission in the French Army and accompanied his parents to England. Sir Richard's hopes centered on his son Edmond Wallace. He hoped that Edmond would found an English family by marrying into an English titled family, preferably a branch of the Seymours. The patent of the baronetcy issued on 28th August, 1871 contained the phrase, “and to heirs male of his body lawfully begotten”. Wallace wanted his son to inherit his baronetcy and appealed to the Queen for an exception for his son, she declined and Wallace was crushed.

Edmond also disliked living in England. He was essentially a Frenchman and he realized that he would never wish to be an English landowner and M.P. He preferred the Bohemian type of life for which Paris was famous. He had a mistress in Paris and had four children with her. Things had come to a head when Edmond told his father of his intention to return to Paris to live. Wallace lost his temper with his son and threatened, blustered, cajoled and pleaded, but all to no avail. They became estranged. Wallace cut the allowance he was making to him. They were never destined to be reconciled. Edmond went to live in Paris and his parents never saw him again. At the early age of 47 Edmond died, still totally estranged from his father and still unmarried. Strange to say Lady Wallace was very little affected by his death. Her stubbornness and insensitivity remained unaltered by the tragic loss. As the years passed she replaced Edmond in her affections with Murray Scott, the Secretary.

It was now downhill all the way for Richard Wallace. He took himself to Paris and began living at Bagatelle. He followed the example of the Fourth Marquis and became a recluse, refusing to see people and holding communication with none if he could avoid it. His wife and Murray Scott remained in London though Scott did make visits to Paris to attend to Sir Richard's wants. They were not very pleasant visits. Wallace's temper had not improved with his isolation and the bulk of it fell upon the shoulders of the tall secretary who took it all without recrimination. When he died in 1890 he bequeathed his entire estate to his widow, Amélie-Julie-Charlotte Castelnau. It was Lady Wallace who on her death in 1897 made what has been described as the greatest ever single bequest of art treasures to a Nation.

In drawing up her will in 1894, Lady Wallace was almost certainly motivated by a desire to honour the wishes of her husband whilst, at the same time, she wished to commemorate his own important role in the formation and preservation of the collection. Lady Wallace bequeathed to the British Nation the pictures and works of art “placed on the ground and first floors and in the galleries at Hertford House”. She also specified that the Government should provide a site to build a new museum and that the collection shall be kept together, unmixed with other objects of art, and shall be styled the Wallace Collection.

The terms of Lady Wallace's bequest mean that the Wallace Collection does not acquire new works of art for its collections. Nor does it normally display works of art from other collections alongside works in the permanent collection. Visitors to the Collection are therefore able to appreciate and enjoy one of the greatest collections ever assembled, essentially in its original form.

Wallace wanted to found an English family as part of the titled, landed proprietors of Britain. That was not to be largely because his son (like himself before him) was loyal to the woman he loved who was the mother of his children. And the bitter tragedy of this sad tale is this, the spurned children of his son were to prove worthy of their grandfather by their valor, their bravery and their industry. The eldest, Georges Richard was born in Paris in 1872 just as his grandfather and father were leaving that city to live in London. He was a captain in the 22nd Dragoons at the outbreak of the Great War throughout which he served. He rose to the rank of General of the French Army, was mentioned no less than nine times in dispatches for conspicuous gallantry, was wounded five times, was made a Commander of the Legion of Honor and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Henry Richard, the second son, also distinguished himself in action on various fronts and was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. The highest accolade was reserved for the youngest son, named after his father Edmond Richard Wallace, born in 1876. He was a lieutenant in the reserves when war broke out and on 28th February, 1915 at Vauquois on the Meuse his regiment was decimated and he was killed at point blank range by a bullet in the head. In the margin of his death certificate are the immortal words “Died for France”. The fourth child was a girl, Georgette Wallace, born in 1878. Gifted with a fine contralto voice, she studied singing and made a career for herself in French opera in the years between the wars. She was in constant demand by leading conductors of those days.

As you might be able to tell, I have been moved by the story of this family. How appropriate is the old saying “Love what you have, not what you want” or the refrain from John Lennon, “Love is all you need” and of course “Money can't make you happy”. This story is a microcosm of the clash between French and English society and culture. Also Wallace lived in a time that that introduced titanic changes in society, the old class system was over and he and his son were products of the new order. Had he just embraced the new world, he might have led a happy old age with a loving wife and adoring grandchildren. Something to think about in our own situations.

References:

Wallace Collection Website: http://www.wallacecollection.org/index.php

Extract of Old Lisburn: http://anextractofreflection.blogspot.fr/2012/03/wallace-collection.html

Lisburn Historical Society: http://lisburn.com/books/historical_society/volume10/volume10-8.html

Life of Wallace: http://www.lisburn.com/books/historical_society/volume3/volume3-2.html