The Musée d’Orangerie was originally built in 1852 as an orangerie or winter shelter for the orange trees destined for the Tuileries Gardens. Over time, the building was used for soldiers, sporting and musical events, industrial exhibitions, and rare painting exhibitions. In 1921, the administration of the Beaux Arts designated the Orangerie as an annex to the overcrowded Musée du Luxembourg.

A cycle of Monet's water-lily paintings, known as the Nymphéas, was arranged on the ground floor of the Orangerie in 1927. They are available under direct diffused light as was originally intended by Monet. The eight paintings are displayed in two oval rooms all along the walls. To celebrate the end of WWI, the French prime minister, Georges Clemenceau, invited his friend Claude Monet to display his large-format nymphéas there. Monet had been working on them since 1914 in a spacious studio added onto his Normandy home in Giverny. And he would continue painting these vast canvases until his death at 86. The following year, in 1927, eight were finally installed and glued to the walls in two specially designed oval-shaped rooms in the Orangerie.

The museum was closed to the public from the end of August 1999 until May 2006. The Orangerie was renovated in order to move the paintings to the upper floor of the gallery. You cannot take pictures there so I include excellent pictures from Bernard Edourd Bigaje, visit his site. I personally sat for half an hour in each room and came out feeling very soothed. It is a setting and experience not to be missed.

A range of early twentieth century art was given to the Orangerie Museum in 1959 by the estate of Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume with the stipulation that the objects be shown as a distinct collection. Today, after the renovation, the paintings and sculptures are located in galleries at the lower level. Renoir is represented at the Orangerie in his later period, from about 1882 onward. This is a fabulous collection and gives me an opportunity to explore the later Renoir here and in a separate post to look at his earlier paintings from a trip we took to the Chicago Art Museum about a year ago (in a separate post).

Although he is famous for sensual nudes and charming scenes of pretty women, Auguste Renoir was a far more complex and thoughtful painter than generally assumed. He was a founding member of the Impressionist movement, nevertheless he ceased to exhibit with the group after 1877, feeling that the Impressionist label made his paintings less marketable (how times have changed). From the 1880s until well into the twentieth century, he developed a monumental, classically inspired style that influenced such avant-garde giants as Pablo Picasso. Renoir's paintings are noted for their vibrant light and saturated colour, most often focusing on people in intimate and candid compositions like the painting shown above. In characteristic Impressionist style, Renoir suggested the details of a scene through freely brushed touches of colour, so that his figures softly fuse with one another and their surroundings. Renoir left for Italy in 1881 to continue his self-education in the “grandeur and simplicity of the ancient painters.” He returned influenced by Raphael and Pompeii and his figures consequently became more crisply drawn and sculptural in character. This has been called his Ingres period. I really love this nude.

This is a nude done just a few years earlier, Little Blue Nude (Petit nu bleu), from 1879. You can see the both the differences and the similarities. In the top painting, the marble or porcelain-like figure is sharply defined against an impressionistically brushed landscape. The spatial relationship between the nude and the amorphous background is deliberately unclear. While the back view of the nude is reminiscent of Ingres, the bushy vegetation and coastal view recall the landscapes Renoir painted on the English Channel island of Guernsey, which he visited in 1883. Notice the difference the background makes in the two paintings. The dark lifeless background below draws none of the colors from the nude and the shadows are black or brown. In opposition, the top painting has shadows of every color and draws from and enhances the perception of the skin of the nude woman. The lesson, in Impressionism you cannot paint a part of a painting without including the color palate in the whole painting. One other small point, if you look carefully at the top left corner of the painting you can almost imagine that it was painted by Marc Chagall. The color palate and forms are eerily similar.

The nude shown above is from 1896 with Renoir in his mature “pearly” period. From about 1890 to 1900, Renoir's style changed again, it no longer was pure Impressionism or the style of Ingres period (the previous ten years), but a mixture of both in the coloristic traditions of Titian and Rubens as well as the unabashedly sensual beauty of eighteenth-century French art. The bodies become somewhat softened, the skin becomes very colorful and, well pearly, and the forms are more fluid unlike the more sculptural Ingres depictions in the preceding 10 years. Also note the Rubenesque figure paired with the trademark glowing skin above. You can see where Picasso got his inspiration for his monumental nudes.

A young woman with “pearly” skin comes slowly out of the water to dry near a rock. The very sweet and innocent face, shot entirely in profile, almost makes it seem like a small animal caught in a forest. The young woman is the sole subject of the painting. With generous hips and her left hand resting on the rock, it fills the space of the canvas. The elements that surround it are quickly sketched and the background, all fogged, remains unknown. Take note of the color palate, in this painting it goes from blue to green in opposition to the top nude which goes from green to blue. Moreover, a characteristic feature of Renoir is a small foreground area painted in focus that draws the eye to start at the bottom of the painting. This painting is a little scandalous since the eye begins at the bottom, moving up the voluptuous body completely uncovered, and only at the end encounters the innocent face. Thus the viewer is put in the somewhat uncomfortable position of a voyeur, and in fact of a young girl judging by the face. Here is a quote from 1896:

“This body of young swimmers, small instinctive beings, child and women both, where Renoir provides both a committed love and malicious observation. It is a special design that says these sensual girls without vice, unconscious humane irresponsible though gently awakened to life … They exist as children, but also players like young animals, and like flowers that absorb air and dew” (Geffroy, 1896)

A lovely quote and an equally lovely, even if risqué, painting.

In the early twentieth century, despite old age and declining health, Renoir persisted in artistic experimentation. The Rubenesque nudes he had been painting reached a level of unprecedented exaggeration in the twentieth century, as seen above, culminating in the massive “Bathers” at the Musée d'Orsay. Mary Cassatt infamously described these pictures as of “enormously fat red women with very small heads.” (I love that quote) Nevertheless, their over-the-top vision of feminine plenitude was admired by Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Aristide Maillol.

The Bathers may also be regarded as Renoir's pictorial last testament, he died in December 1919. It was in this spirit that his three sons, among them the filmmaker John Renoir, gave the painting to the State in 1923.

In the early 1890s, friends and admirers of Renoir took exception to the fact that the French State had never made any official purchase from the painter, then almost fifty years old. In 1892, Stéphane Mallarmé, who knew and admired the artist, helped by Roger Marx, a young member of the Beaux Arts administration and open to new trends, took steps to bring Impressionist works into the national museums. This was how, following an informal commission from the administration, Young Girls at the Piano was acquired and placed in the Musée du Luxembourg. Renoir made five versions of Two Young Girls at the Piano for the Minister of Fine Arts to choose from. The subject of girls at a piano recalls eighteenth-century French genre scenes, especially those of Fragonard. Renoir had painted the subject several times before, most notably in a major portrait commission.

We know of three other finished versions using the same composition (one in the Metropolitan Museum de New York and the two others in private collections). There also exists a sketch in oils (Paris, Musée de l'Orangerie) and a pastel of the same size (private collection). The repetition of this motif shows Renoir's interest for a subject he had already treated and would treat again as shown above. We know that the painter was always dissatisfied and kept on reworking his paintings, but such a concentrated effort on one and the same composition remains unique, perhaps influenced by the serial paintings of Monet. Maybe we should see in this his desire to provide the museums with a perfectly accomplished work. Notice the difference in technique between the upper and lower painting separated by only about six years.

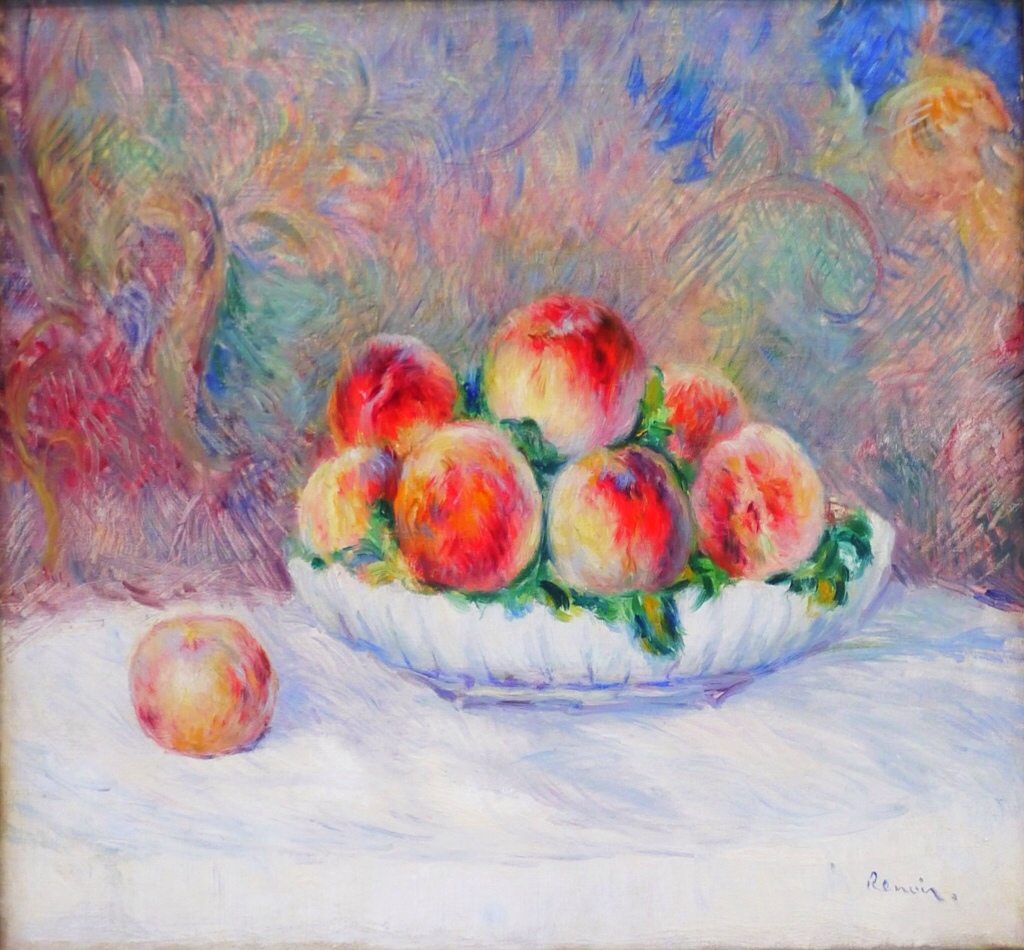

Renoir's skills for portraiture attracted the attention of a range of patrons with avant-garde sensibilities. Renoir painted all of his patrons with affectionate charm. Marguerite Charpentier was the wife of the publisher Georges Charpentier and hostess of one of the most fashionable salons in Paris, at which Renoir was a regular guest. Renoir, in fact, met one of his best patrons, the banker Paul Bérard, at Mme Charpentier's home. Renoir painted all of his children and visited the Bérards' country house in Wargemont (in Normandy) regularly, where he explored other genres such as seascapes and still life's like the exquisite painting of peaches shown above.

Reviewers of the 1882 Impressionist exhibition were dazzled by a “very appealing” still life of “a certain fruit bowl of “Peaches”, whose velvety execution verges on a trompe l'oeil.” Painted the previous summer at the country house of his patron Paul Bérard, it is one of two still lifes that feature the same bowl. Notice the difference the background makes in these two paintings. The top one from the Orangerie has an impressionist background that really lights up the painting. This is true to the impressionist ideas that the color of an object is influenced by the nearby colors. The bottom painting from the Met has beautifully rendered fruit but the colors are more restrained and the background is much more classical. As a result, we don't get the “pop” that we associate with Impressionism. Conversely, you can easily see why the reviewers of 1882 liked the bottom one. Somewhat like an acquired taste in food, Impressionistic painting has to be accepted by the viewer as a whole.

Late in his life, his still lifes became more drab with plain brown backgrounds, as shown above in a painting of strawberries from 1905 and the one below of peaches from 1916, sold at Christie's in 2001. The Musée de L'Orangerie is a great museum with lots more than I have shown. It is conveniently located in the Tuileries on the far side from the Louvre which will be much more crowded. Think about a visit if you come to Paris.

References:

American Friends Musée D'Orsay: http://aforsay.org/musee-de-lorangerie/

Bernard Edourd Bigaje: http://bebgalerie.voila.net/photos.html

Musée Orangerie: http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/

Met Museum Renoir: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/augu/hd_augu.htm

Baigneuse aux cheveux longs: http://www.musee-orangerie.fr/pages/page_id19457_u1l2.htm

Bather with long hair: http://aidart.fr/galerie-maitres/impressionnisme/baigneuse-aux-cheveux-longs-renoir-vers-1895-1107.html

Renoir Gallery: http://www.renoirgallery.com/biography.asp