Throughout the 2nd millennium BCE there existed in Costa Rica small, disperse villages, non-nomadic agricultural communities that used ceramic bowls and utensils, and tools made from wood, bone and stone for agricultural tasks and food preparation. The oldest of these agricultural village communities (2000–500 BCE) has been found in the province of Guanacaste. More recent ones (1500–300 BCE) have been discovered in the Turrialba Valley, the coastal region of Gandoca, the northern plains, Sarapiquí Basin, Barva, Herradura, the Térraba River Basin, the Coto Colorado River Basin and Isla del Caño. Between 300 BCE and 300 CE many communities moved from a tribal, clan-centric organization (kinship-based, rarely hierarchical) and dependent on self-sustenance, to a hierarchical one, with caciques (chiefs), religious leaders or shamans, artisan specialists and so on. This social organization arose from the need to organize manufacture and trade, manage relations with other communities and plan offensive and defensive activities. These chiefdom groups in general established territorial divisions that were more strongly demarcated than those in tribal times, and were able to expand their geographical spheres of domination to produce more food and control expanding sources of raw materials.

Ornamental Jade

Jade ornaments were likely valued in Costa Rica for both their green color and the strength and luster of the stone. They undoubtedly gained additional prestige through the material’s origin in distant lands (the only known source of jadeite in the Americas is the Motagua Valley of highland Guatemala). Much of the jade was probably imported to Costa Rica in the form of celts, or axe-blades, that could then be worked locally into a variety of pendants, beads, or small sculptures. Because of jadeite’s toughness (resistance to chipping or shattering), it was the ideal tool for axe blades, used throughout the Americas to clear the forest for agriculture. The bulk of Costa Rican jades contain drilled holes so they can be utilized to decorate the body in bead and pendant form. There are three main types; Axe Gods, Beak Birds and Bar Pendants.

There are two types of Axe God figurines, Avian and Anthropomorphic. The earliest known jade work is the Avian axe god celt found at the site of La Regla, dated at 500 BC.

Beak Birds are characteristic for their large, stylized beak. All were drilled through their neck so when strung to hang the beak would be projecting. The figures are very diverse in size and shape. The beaks are either straight, or curved pointing up or down.

There was a great development in the manufacture of objects made of jadeite or so-called “social” jade (green or off-white stones such as quartz, chalcedony, opal, serpentine, etc.). It is supposed that they were used as personal ornaments then later on in individual burial clothes, since most have been found at burial sites. Deep local tradition in jade-work (which began around 500 BC and continued until around AD 700) for the most part developed without external influence, although some pieces display features of Olmec and Mayan artisanship. Their motifs apparently had religious meaning. Burials from this period demonstrate the existence of rank and class, since burial offerings include artifacts made of jade and other green gemstones, ceremonial grinding stones, sceptre stones and elaborate ceramics. The number, quality and difficulty of obtaining these articles are a means of indicating the person’s social rank.

Earliest Costa Rica Pottery

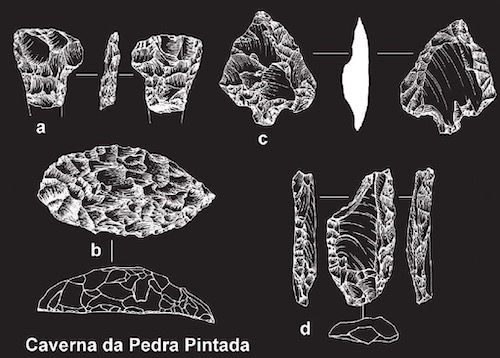

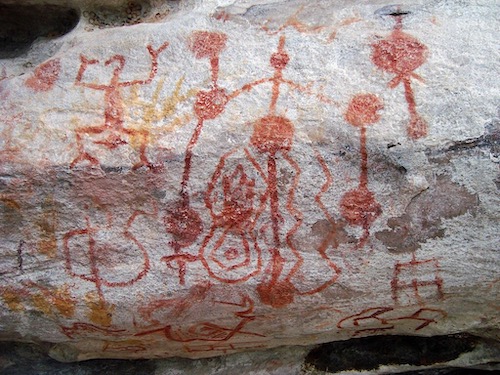

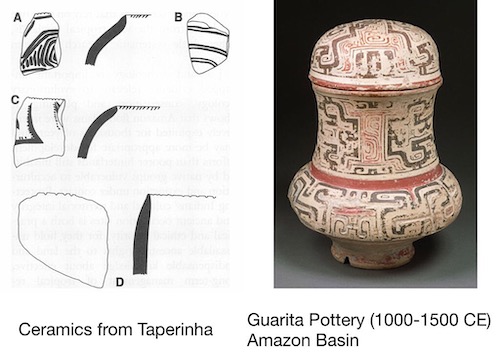

The earliest ceramics known from the Americas have been found in the lower Amazon Basin. Ceramics from the Caverna de Pedra Pintada, near Santarém, Brazil, have been dated to 7,500 to 5,000 years ago. Ceramics from Taperinha, also near Santarém, have been dated to 7,000 to 6,000 years ago. The Guarita sub-tradition, starting around 500 CE, has been reported for various sites, such as Mangueiras, Manacapurú, Açutuba, Osvaldo, Lago Grande and Hatahara.

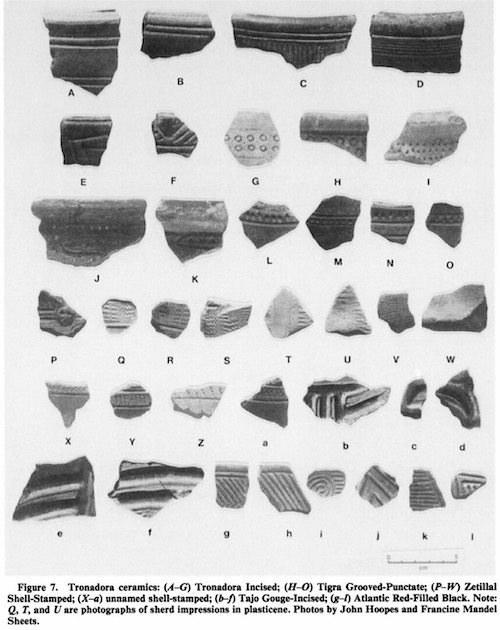

By 2000 BCE pottery had appeared in the land-bridge cultural record, represented by two geographically disjunct and very different traditions: Monagrillo in central Panama (2500–1200 BCE) and Early Tronadora in northwest Costa Rica (1890 BCE).

Formative Period Pottery In Costa Rica

Costa Rica has three basic archaeological regions, each with a different cultural chronology: the Nicoya, extending into Nicaragua, in the North; the central Atlantic Watershed and Highland; and the Diquis/Chiriquí, extending into Panama, in the south. The Nicoya region seems to have been part of the Formative Period picture around 1000 BCE when a period defined as Zoned Bichrome, lasting until 300 CE, is recognized. The Atlantic Watershed and Highland Region’s Early Period extends from 300 BCE to 300 CE, a time when most of the above-mentioned ceramics were present. In the Diquis Region, the Early Period stretches from 0 to 800 CE. Although many of the basic traits which delineate Formative Period culture appear along with local characteristics throughout Costa Rica, much of the painted decoration is absent.

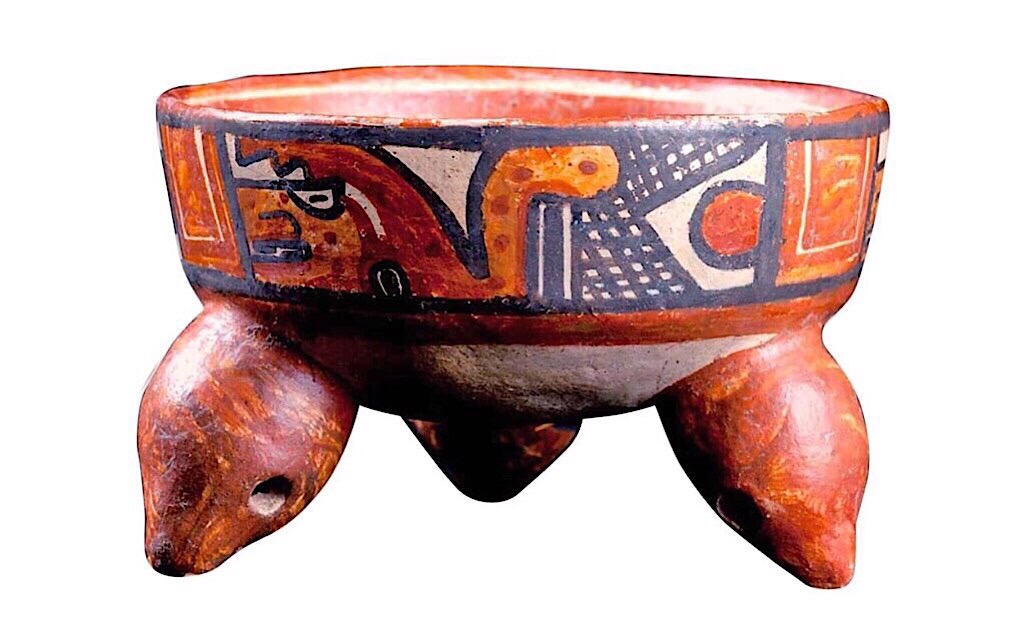

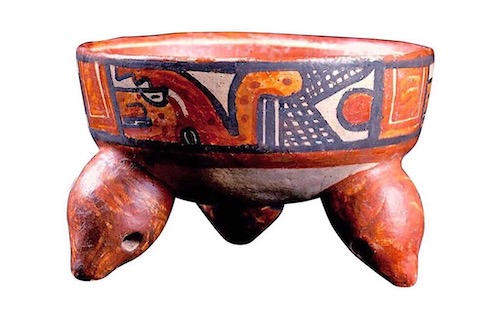

La Selva Tripod Pottery

Of particular note is the widespread tripod pottery which is found throughout Costa Rica, but particularly in the Atlantic Watershed and Highlands. By about 300 CE, Costa Rican natives were living in the east-central part of the land that is known as the Atlantic Watershed which is a tropical rainforest that was called La Selva, a Spanish term meaning “the jungle”. They developed three leg type pottery that has been given several names including Africa tripods, spider-leg vessels, chocolate pots and zoomorphic tripods. They all have certain common features, three legs with zoomorphic and/or anthropomorphic (human shapes combined with animal or god-like beings) embellishments enclosing a vase or cup-like container. Most have hollow legs inside which are stone or clay balls that rattle when the vessels are shaken or moved. Various zoomorphic images are usually at or near the juncture of the limbs and the bowl and some have animal forms actually modeled against the outside surface of the container. These La Selva tripods are often tall and graceful with the long sinuous tapered legs and gourd shaped bowls enclosed within the trio of supports and were thought to be ceremonial objects for burning incense.

Censers or Incense Burners

Censers are ceremonial containers used for burning incense, a substance which plays an important role around the world in various religious ceremonies; in many cases the smoke is thought to ‘coat’ the participating members in the same smell and act as a visual cue for communication between humans and the spirit world. Almost 400 species of plants were reportedly burned for incense purposes throughout the world, with copal (gums, and resins) commonly used in Mesoamerica. Most often, American copals are resins from various members of the tropical Burseraceae (torchwood) tree family. Other resin-bearing plants that are known or suspected of being American sources of copal include Hymenaea, a legume; Pinus (pines or pinyons); Jatropha (spurges); and Rhus (sumac). Why this particular shape was preferred over others for burning incense is unknown.

Historically, the Lacandón Maya made copal from the pitch pine tree (Pinus pseudostrobus). To the Maya the burning of copal gum was considered so vital that it was known as “the super odor of the center of heaven … and the brains of heaven”. The aroma of burning resins was supposed to please the gods and make them amenable to granting worshippers’ wishes. To Maya devotees smoke represented an ascending prayer. Its smoke also provided a route for the ascent of the soul of a deceased person. The smoke was also thought to have healing and purifying power. The gum or resin that served as incense was taken from trees and was considered the “blood” of the tree. Among peoples from southern Nicaragua to Mesoamerica, and particularly among the Nicoya people, the earth was likened to the back of a crocodile floating in the primordial sea, its dorsal scutes being the volcanic north-south backbone that defines the continents of the Western Hemisphere. Many such incense burners were found ritually broken on the slopes of a principal volcano on the island of Ometepe in Lake Nicaragua, the incense burner lid with its smoke issuing from the top mimicking an active volcano. These incense burners are profound ritual vessels pertaining to the transition from the natural to the supernatural realms and a symbolic model of the ancient Costa Rican world.

Costa Rica Fusion of Cultures

Based upon current archaeological studies, it is believed that the art and culture of the natives of Costa Rica were heavily influenced by intrusions from the Olmec and Mayan entities of Mexico and Guatemala and by various civilizations living in Columbia, Ecuador and Peru in South America. Around 300 CE, the Nicoya, Atlantic Watershed and Highland Regions had new elements, including human and zoomorphic effigy figurines; vessels with the form of an elongated gourd called ifcara (Calabash tree): clay mushroom effigy vessels; Amazonian-style tapering pottery drums; rattles; and nasal snuffers with one or two tubes. These traits represent the fusion of cultures in Costa Rica, and illustrate the importance of Central America as a meeting-ground of southern and northern cultures.

I hope you enjoyed this post, it is an overview of subjects I will be treating in more detail in the future. I have tried, when possible, to use objects from the expansive and excellent Denver Art Museum Pre-Columbian Art Collection, since I want my readers to be aware of its existence. This is such a fine resource that it is worthwhile to visit as an end destination or at the very least as a day trip on your visit to Denver. As always please leave comments or questions below.

References:

Ancient Costa Rica: Denver Art Museum

The Tronadora Complex: Early Formative Ceramics in Northwestern Costa Rica

A Synthesis of Pre-Columbian Ceramics from Costa Rica

A Comparison of Iconography from Northwestern Costa Rica and Central Mexico

Ancient Costa Rica: Denver Art Museum

Jade in Costa Rica. Met Museum

Costa Rica Jade Museum in San Jose

The Zoomorphic Tripod Vessels of La Selva

A Re-examination of Potosí Applique Censers from Greater Nicoya

Nature and Artistry in the Ancient Americas

Copal, the Blood of Trees: Sacred Source of Maya and Aztec Incense

A Complex of Ritual and Ideology Shared by Mesoamerica and the Ancient Near East