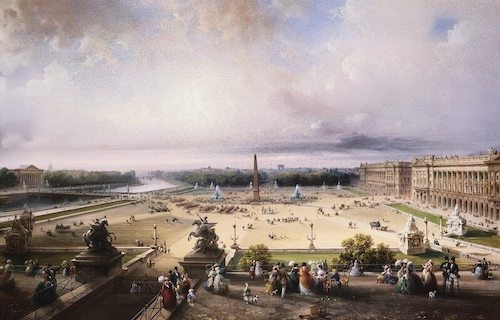

The Place de la Concorde was designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel in 1755 as a moat-skirted octagon between the Champs-Élysées to the west and the Tuileries Garden to the east. Decorated with statues and fountains, the area was named Place Louis XV to honor the king at that time. The square showcased an equestrian statue of the king, which had been commissioned in 1748 by the city of Paris, sculpted mostly by Edmé Bouchardon, and completed by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle after the death of Bouchardon. During the French Revolution the statue of Louis XV of France was torn down and the area renamed Place de la Révolution or Place de la Guillotine. The new revolutionary government erected the guillotine in the square, and it was here that King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed. In 1795, under the Directory, the square was renamed Place de la Concorde as a gesture of reconciliation after the turmoil of the French Revolution. During the reinstitution of the monarchy the name changed but after the the July Revolution of 1830 the name was returned to Place de la Concorde and has remained the same since. Measuring 8.64 hectares (21.3 acres) in area, it is the largest square in Paris.

The last watercolor, perhaps commissioned by Princess Eugenie, is a fascinating window into France under the reign of Louis Philippe. Dated 1853, the picture celebrates the completion of this square so filled with the echoes of French history. It also provides an idyllic image of the Parisian bourgoise admiring the parade of military power and the precision of the Garde Republicane. The Egyptian obelisk in the center – the near twin of Cleopatra's needle in London was a gift from Mohammed Ali, Viceroy of Egypt. The Place de la Concorde was designed to impress, originally a testimony to the 18th century splendor of the absolute monarchy. Virtually all of the buildings and monuments in view here are potent symbols of French prestige, whether monarchist, imperial or republican. Across the bridge on the left is the Palais Bourbon that now houses the National Assembly. Originally built in 1728 for the Duchesse de Bourbon, daughter of Louis XIV, the facade, the only part clearly visible, was redone by Napoleon in the Greek revival style. Napoleon's shadow looms over the left bank with the dome of the Invalides where he was finally buried in 1840. The Obelisk pulls the viewer's gaze up through the Arc de Triomphe which presides over the Champs Elysées as the quintessential monument to Napoleon's victories in battle.

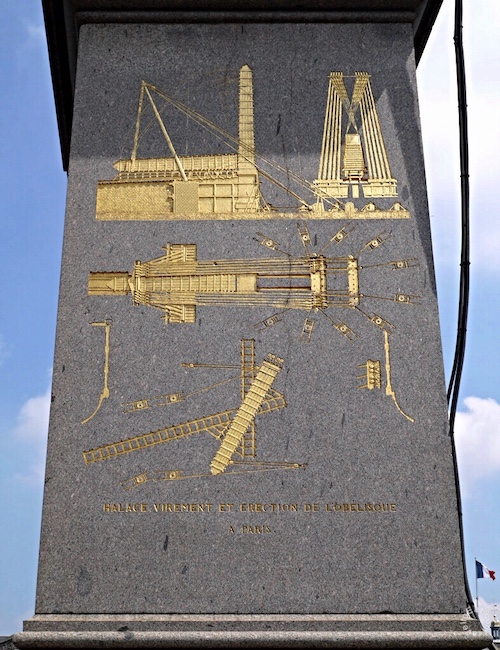

Obeliskes were originally called “tekhenu” by the builders, the Ancient Egyptians. The Greeks who saw them used the Greek 'obeliskos' to describe them, and this word passed into Latin and then English. The Luxor Obelisk (Obélisque de Louxor) is a yellow granite column, riseing 23 meters (75 ft) high, including the base, and weighs over 250 metric tons (280 short tons). Given the technical limitations of the day, transporting it was no easy feat, on the pedestal are diagrams explaining the machinery that was used for the transportation and erection. The French government ordered a purpose built seagoing lighter built by the Toulon naval yard; This 49 metres long, flat bottomed, three masted ship named the Louxor was sailed up the Nile to Louqsor where 300 workmen dug a canal to allow the ship to come close to the obelisk. The team of French seamen carefully lowered the oblisk with a complicated array of blocks and tackles, yardarms and capstans. The re-erection of the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde during a ceremony carefully planned by Louis-Philippe was no mean engineering feat either. The obelisk is flanked on both sides by fountains constructed at the time of its erection on the Place. The Egyptian viceroy Muhammad Ali Pasha presented the obelisk as a gift to Charles X in 1829 and Louis-Philippe installed it in its current location in 1836. Louis Philippe, bearing in mind the death and destruction witnessed by Place de la Concorde, was pleased to have found a non-political monument to replace the unpopular Louis XV statue.

The original Egyptian pedestal included the statues of sixteen fully sexed baboons and was deemed too obscene for public exhibition, it is displayed in the Egyptian section of the Musée du Louvre. We probably do not completely comprehend the significance of monkeys and baboons in Egyptian religious symbolism, but there is no doubt that they were kept as ritual animals since the earliest periods of Egyptian history. The baboon also became an aspect of the sun god Re, as well as of the moon god Thoth-Khonsu. The ancient Egyptians who observed the baboon barking at the rising sun gave rise to a favorite theme in sculpture, paintings and reliefs of a baboon worshiping the sun with raised hands. This aspect of baboons fits perfectly with the function of obelisks, which are temples to the sun god Ra. The obelisk symbolized the sun god Ra, and during the brief religious reformation of Akhenaten was said to be a petrified ray of the Aten, the sundisk. It was also thought that the god existed within the structure.

The two fountains in the Place de la Concorde have become the most famous of the fountains built during the time of Louis-Philippe, and came to symbolize the fountains in Paris. They were designed by Jacques Ignace Hittorff, a student of the Neoclassical designer Charles Percier at the École des Beaux-Arts. The German-born Hittorff had served as the official Architect of Festivals and Ceremonies for the deposed King Charles X (in the July Revolution of 1830), and had spent two years studying the architecture and fountains of Italy. Both fountains had the same form: a stone basin; six figures of tritons or naiads holding fish spouting water; six seated allegorical figures, their feet on the prows of ships, supporting the pedestal, of the circular vasque; four statues of different forms of genius in arts or crafts supporting the upper inverted upper vasque; whose water shot up and then cascaded down to the lower vasque and then the basin. These fountains were just one part of a larger French Restoration period by Louis-Phillipe in which Hittorff replanted the gardens of the Champs-Élysées. He kept the formal gardens and flowerbeds essentially intact, but turned the garden into a sort of outdoor amusement park with outdoor restaurants and entertainment venues.

The elegant lamp posts in the Place de la Concorde have been the subject of many comments, photographs and paintings. The first four Paris municipal gas lamps were illuminated on the place du Carrousel in 1829, along with twelve more on the rue de Rivoli. The experiment was judged a success, a design for a lamppost was selected and gas lamps appeared the same year on rue de la Paix, place Vendôme, rue de l'Odeon and rue de Castiglione. According to Galignani's “Guide to Paris” (1844) the gas lamp posts in the Place de la Concorde were installed in 1836 along with the fountains and Luxor Obelisk. I cannot find the actual designer, but the neo-classical style is very similar to the fountains, indicating they were designed to compliment the fountains by Jacques Ignace Hittorff or one of his associates. Between 1853 and 1870 Haussmann placed more utilitarian street lamps every twenty meters on the boulevards of Paris. At a predetermined minute after nightfall a small army of 750 allumeurs in uniform, carrying long poles with small lamps at the end, went out into the streets, turned on a pipe of gas inside each lamppost, and lit the lamp. The entire city was illuminated within forty minutes. The Paris gas lamps were apparently very influential on municipal lamps designed elsewhere. Percy Fitzgerald, writing in the Magazine of Art in 1880, argued that the lamps on the (Thames) embankment in London were ‘too trifling in character to need such massive bases’ and, in a telling comparison, condemned Vulliamy’s “attenuated” lamp posts in contrast to those found in Paris, which he regarded as “elegant” objects.

At the north end, two magnificent identical stone buildings were constructed. Separated by the rue Royale, these structures remain among the best examples of Louis Quinze style architecture. Initially they served as government offices, with the eastern one being the home of the French Naval Ministry. Shortly after its construction, the western building was made into the luxurious Hôtel de Crillon, which is still operating today, it is here that Marie Antoinette spent afternoons relaxing and taking piano lessons. The hotel also served as the headquarters of the occupying German army during World War II. In November 2010, the French online newsource “Challenges” reported the sale of the hotel to the Saudi Arabian royal family member Prince Mitab Ben Abdalah ben Abd al-Aziz Al Saoud. In December 2013, it was announced that Rosewood Hotels & Resorts would manage the hotel once it reopens in 2015 from a major renovation.

The Place de la Concorde is bound on the west by the Champs Élisée and to the east by the Tuileries Gardens and Louvre.

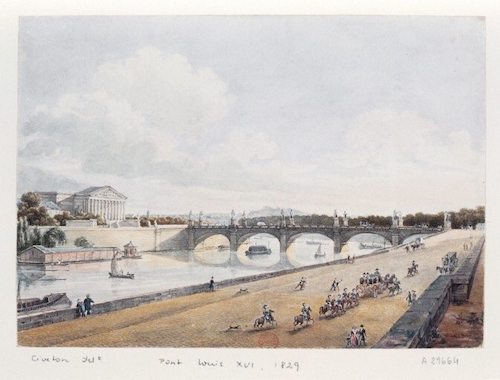

If Notre Dame Cathedral is the heart of Paris, then Place de Concorde is the true historic and political center of Paris. To the south the Pont de la Concorde (Bridge of Concord) leads from the Place de la Concorde to the Palais Bourbon, home of the French Parliament's lower house. Already planned in 1725, the bridge was built after much delay, between 1787 and 1791. To the north is the Rue Royal leading to L'église de la Madeleine. Both the Palais Bourbon and Madeleine were transformed by Napoleon Bonaparte. Next time you visit Paris, brave the traffic swirling around the Place Concorde and take a moment to admire the fountains, obelisk, lamp posts and views from this historic vantage point.

[mappress mapid=”141″]

References:

Musée Carnavalet: http://www.carnavalet.paris.fr/en/homepage

Carlo Bossoli: http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/LotDetailsPrintable.aspx?intObjectID=343889

Paris During the Restoration: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_during_the_Restoration

Baboons and Monkeys: http://m.touregypt.net/featurestories/baboons.htm

Hotel Crillon: http://www.crillon.com/en/

London Lamp Posts: http://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/2012/05/22/representing-the-nation-the-thames-embankment-lamps/

Charles Marville: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/paris-reborn-and-destroyed

Luxor Temple: /evening-at-the-temple-of-luxor-egypt/#more-12586

Église de la Madeleine: /eglise-de-la-madeleine-paris/

Victoria and Albert Museum: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/creating-new-europe-1600-1800-galleries/born-on-this-day-the-bridge-builder