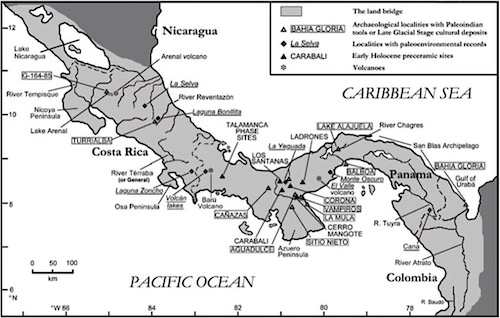

Since I am visiting Costa Rica for a bird photography tour, I thought I would write a post on the pre-Colombian cultures of this area. Costa Rica appeared to be a dynamic, fluctuating frontier zone between two major spheres of pre-Columbian cultural influence: Mesoamerica (central Mexico through El Salvador) and northern South America, primarily Colombia. There is archaeological evidence that places the arrival of the first humans to Costa Rica between 7,000 and 10,000 BC. In the valley of Turrialba, sites have been found in areas where quarry and tradesman tools such as biface stone tools were manufactured. The Central American land bridge has served as a passageway for animals and humans moving between North and South America for thousands of years. Because it was not home to ancient state societies but was predominated by chiefdoms at the time of the Spanish conquest, it was sometimes regarded as a kind of “cultural backwater” that contributed little to the emergence of Pre-Columbian civilization in the New World. However, recent archaeological research has demonstrated that this part of the Americas had some of the earliest agriculture, pottery, and metallurgy in the hemisphere. It is likely to have played a critical role in the transmission of culture both to and between neighboring regions to the north and south.

The Central American Land Bridge

Since it is unlikely that the first human immigrants into South America skipped the land bridge by making direct sea crossings, the antiquity and geography of the earliest human occupation is important for understanding the timing and nature of human dispersal into this continent. The very early humans in the Americas have been called “paleoindians” and were present in North America as far back as 16,000 years before the present. Since the first humans came through this area so long ago, not much evidence remains. Archeologists rely on stone tools, marks on animal bones and ancient campfires to make observations on these ancient people. There is archaeological evidence that places the arrival of the first humans to Costa Rica between 7,000 and 10,000 BC. In the valley of Turrialba sites have been found in areas where quarry and tradesman tools such as bifaces were manufactured. It is thought that these first settlers of Costa Rica belonged to small nomadic groups of around 20 to 30 members bound by kinship, which moved continually to hunt animals and gather roots and wild plants. In addition to the species that still exist today, their usual prey animals included the so-called mega-fauna such as giant armadillos, sloths and mastodons.

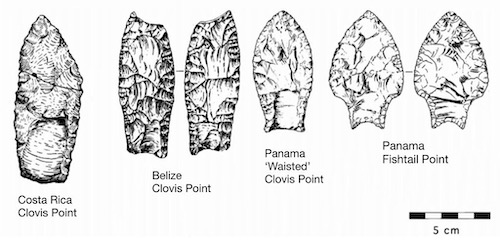

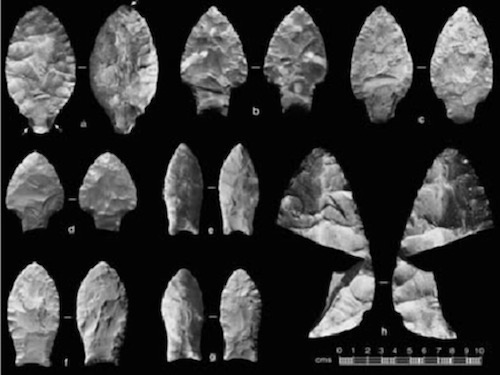

Fell’s cave lies near the Magellan Straights near the southernmost edge of Chile. This was the first site to provide evidence of late paleoindian occupation in South America, and it is the site where the Fishtail projectile point type was defined. Radiocarbon ages from Fell’s Cave on charcoal samples from three hearths yielded dates ranging from ca. 11,000 to 10,100 radiocarbon years ago. The discovery of Fell’s cave came just a few years after the discovery of the Clovis complex in 1929 in Clovis New Mexico, which, was believed at the time, to defined the first human occupation in North America. It appears around 11,500–11,000 at the end of the last glacial period, and is characterized by the manufacture of “Clovis points” and distinctive bone and ivory tools. Thus the Clovis stone projectile points came to represent the first humans in North America while the Fishtail or Fell’s points symbolized the first humans in South America. Both forms are found in Costa Rica and the theory is that Fishtail points evolved from Clovis points.

Nothing is as simple as it first seems. Many pre-Clovis sites have now been identified and it is now clear that the first humans in the Americas were not Clovis. The oldest claimed human archaeological site in the Americas is the Pedra Furada hearths, a site in Brazil that precedes the Clovis culture by a staggering 19,000 to 30,000 years. This claim has become an issue of contention between North American archaeologists and their South American and European counterparts, who disagree on whether it is conclusively proven to be an older human site.

The Neolithic in Costa Rica

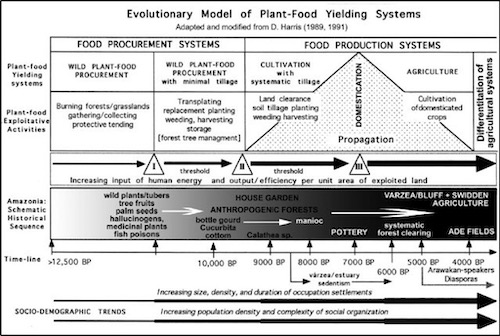

The earliest dated maize cob was discovered in Guilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca, Mexico and dates back to 4300 BCE although it was probably present even earlier. Maize and manioc (or cassava), domesticated outside the land bridge, were introduced before pottery was made, early in the period between 5000 and 2500 BCE, and gradually dominated regional agriculture as they became more productive, and as human populations increased and spread into virgin areas. Maize, beans, and squash form a triad of products, commonly referred to by nutritionists as the “Three Sisters.” Growing these three crops together helps to retain nutrients in the soil and provides a healthy diet. They also cultivated fruit and palm trees. Agriculture emerged slowly, stemming from knowledge of the annual cycles of nature and the progressive domestication of familiar plants. This development occurred over thousands of years and coexisted with traditional hunting and gathering, but it afforded a certain amount of stability. To ensure subsistence of these groups there had to exist forms of collective work and property, as well as egalitarian relationships. When the Europeans arrived, Costa Rica was not a unified land but was inhabited by diverse peoples independent from each other, and whose respective cultures had many different levels of complexity and development. It was basically a melting pot of the Colombian, Mesoamerican and Caribbean cultures that surrounded it.

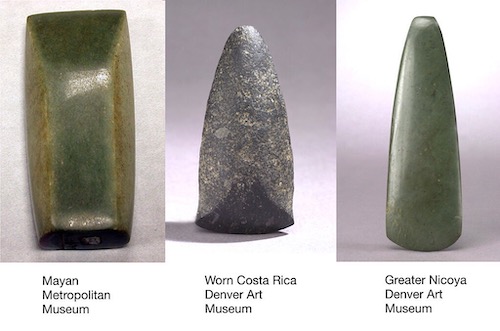

Stone Tools

In archaeology, a celt is a long, thin, prehistoric, stone or bronze tool similar to an adze, a hoe or axe-like tool. A shoe-last celt (German: Schuhleistenkeil) is a long thin polished stone tool for felling trees and woodworking, an important activity in Mesoamerica as trees were felled for timber, lime production and to create fields for agriculture. The fall of the Mayan civilization might be traced to the large amounts of wood they burned to convert limestone to mortar. Greenstone axe heads, commonly known as “celts,” were some of the most important works of art across ancient Mesoamerica and Central America. Created from jadeite mined from the Motagua River Valley of southern Guatemala, or using local green stones from highland Mexico, celts were first created by the Olmec peoples of the Gulf Coast after 1000 B.C. The Olmec conceived green celts as sprouts of maize and thus “planted” celts in dedicatory offerings, activating ceremonial spaces and perpetuating agricultural fertility. Celts also held value for ancient peoples in Central America, including Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Costa Rican deposits are especially rich with greenstone celts, often having been split into halves, thirds, or sixths, and then drilled with a transverse whole so that the celt-shaped pendant could be worn. Sometimes the Costa Rican materials were clearly traded down from Mesoamerica; Olmec and Maya motifs remain on some of the reworked pendants recovered further south. The celts were often transformed into anthropomorphic or avian characters, but tended to always retain a bladed shape. Though the original meaning of Olmec and Maya celts related to the production of maize may have been lost when they reached Costa Rica, greenstone as a valuable material endured well into the late 1st millennium A.D.

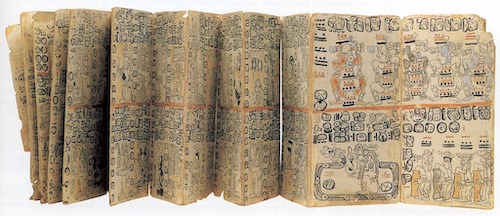

Bark-cloth or Tapa is made by beating sodden strips of the fibrous inner bark of certain trees into sheets, which are then finished into a variety of items. Many texts that mention “paper” clothing are actually referring to barkcloth. Scholars have long recognised the important role bark cloth plays in portraying status in Polynesian societies and in Southeast Asia where it is thought to originate. The earliest bark-cloth beaters in Mesoamerica come from sites in the Maya area and its periphery, particularly along the coasts of Guatemala and El Salvador, where they first appear about 2500 years ago. The technology then moved westwards and eastwards from the Maya homeland. Some have maintained that the above-mentioned parallels are the result of pre-Columbian contact with Southeast Asia or China, where the technology first appeared about 5000 years ago, but the proposition has been met with scepticism by archaeologists.

The Madrid Codex (also known as the Tro-Cortesianus Codex or the Troano Codex) is one of three surviving pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology (900–1521 CE). The Madrid Codex is held by the Museo de América in Madrid and is considered to be the most important piece in its collection. The Codex was made from a long strip of amate bark paper that was folded up accordion-style. This paper was then coated with a thin layer of fine stucco, which was used as the painting surface. The development of paper in Mesoamerica parallels that of China and Egypt, which used rice and papyrus respectively. It is not known exactly where or when papermaking began in Mesoamerica. The oldest known amate paper was discovered at the site of Huitzilapa, Jalisco dating to 75 CE. Rather than being produced from Jamaican Nettletree (Trema micrantha), from which modern amate is made, the amate found at Huitzilapa is made from Strangler Fig (Ficus tecolutensis). It was made with similar beaters used to make cloth.

A metate or metlatl (or mealing stone) is a type or variety of quern, a ground stone tool used for processing grain and seeds. In traditional Mesoamerican culture, metates were typically used by women who would grind lime-treated maize and other organic materials during food preparation. Carved, volcanic-stone ceremonial metates represent one of the most unusual and complex traditions of pre-Columbian artifacts from Costa Rica. They come in many different forms, and morphological variation corresponds to different regions and time periods. They can be rectangular, circular, flat, or curved. They may or may not have rims and between three and four legs. Some exhibits show signs of use-wear while others show no signs of wear and appear to have been made specifically for use as burial goods. Some examples characterized as metate might have actually been a type of throne for sitting on, not a metate at all. The most complex type of ceremonial metate is the class referred to as “flying-panel” metate. This style comes from the Atlantic watershed region, including the City of Guayabo and represents a high level of craftsmanship and complexity. The “flying panel” metate is believed to be the precursor to free standing sculptural figures more common later in the Atlantic watershed region.

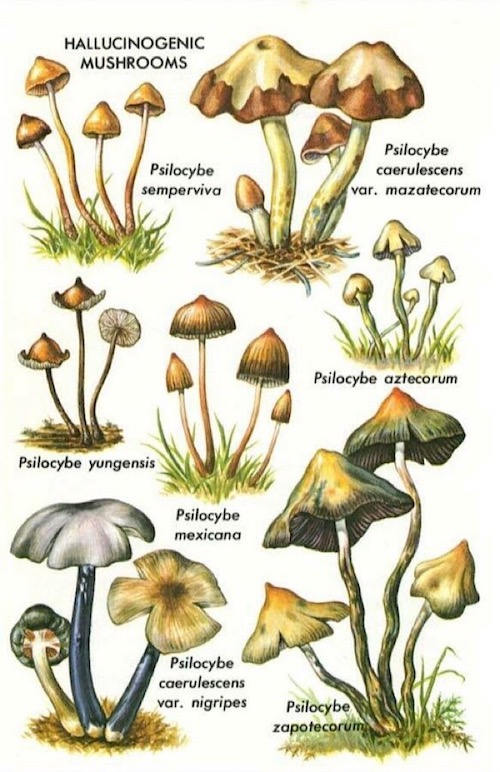

The “mushroom” stone type appears in European museums in the late 19th century including one at the British Museum accessioned in 1869. These enigmatic figures date from the Preclassic into the Classic era. They are found primarily in the Guatemalan highlands and also in parts of Oaxaca and Chiapas, with a large group studied in the 1950’s by Kidder and Shook in the excavations in Kaminaljuyu. Most examples are squatting figures with the dome projecting from the head. Believed to represent a “mushroom” cult of the hallucinogenic species Amanita muscaria and Psilocybin mushrooms, some mushroom stones were found in association with metates and manos used for the ritual preparations. The acrobat stance on this figure is rare within the corpus, however the posture is well represented in numerous Pre-Columbian cultures as part of the shaman’s contortions in trance ceremonies. This culture diffused into Costa Rica although the missionaries made every effort to destroy stone and ceramic mushroom effigies.

While early man had spears for hunting and war, they also used stone for clubs or maces. In Costa Rica, nearly all of these clubs represent a head, human or animal. They can be classified in groups according to their shape. All the clubs are comparatively small and are perforated in the center by a large circular hole for the handle which has been drilled through them. In the head shaped club, it is the large and heavy front portion which is carved into a face or head, while the posterior half is simply ring-shaped with rather thin walls. In the clubs which embody birds or alligators and have the perforations in the center of the body, the back portion (tail) is cone-shaped. The highly ornamental, zoomorphic features of these implements and their size, which is in many causes too small to have admitted of their use for practical purposes, bear witness to their purely symbolical and ceremonial character. Sadly we will never know for sure, many of these artifacts have been stolen from their original locations and sold rather freely in the antiquities marketplace.

I hope you enjoyed the post, next we will delve into ornamental jade and pottery from pre-columbian Costa Rica. Please fell free to leave a comment or question.

References:

Anthrochef: History of Foods in Mesoamerica

Paleoindian occupation in the central American tropics

Human Settlement of Central America and Northernmost South America (14,000–8000 BP)

The Archaeology of Agriculture in Ancient Amazonia

Clovis Points from Blackwater Draw New Mexico

Celts, Adzes, Axes, And Chisels – Pecked And Ground Stone Tools

Trans-oceanic transfer of bark-cloth technology from South China–Southeast Asia to Mesoamerica?