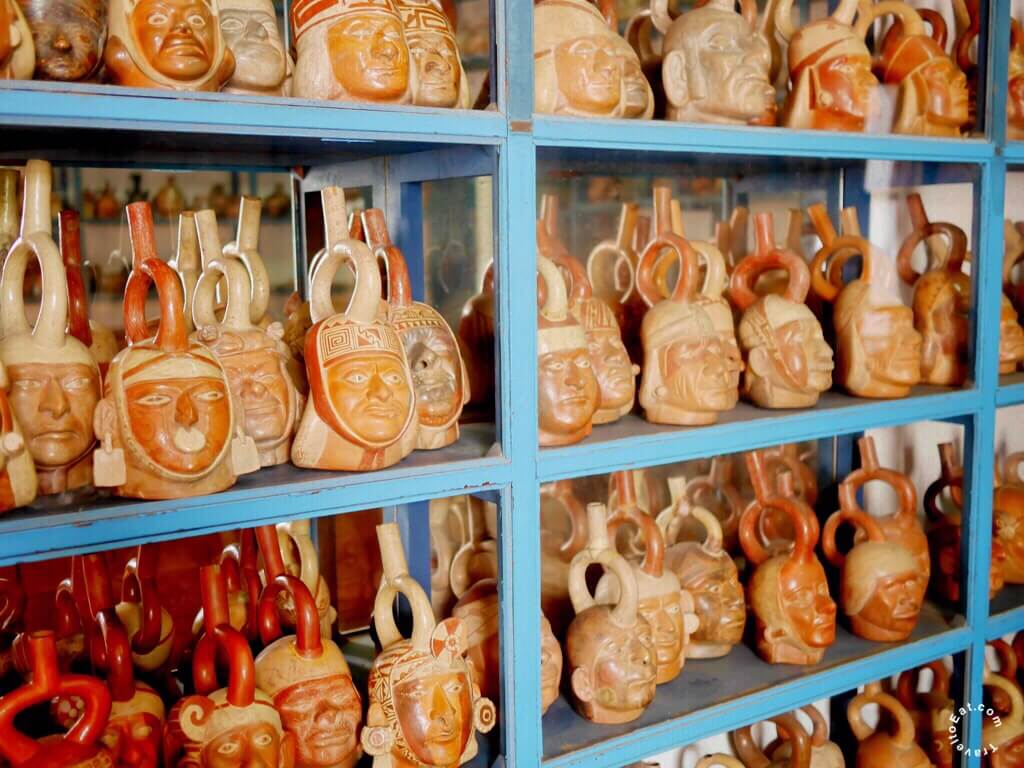

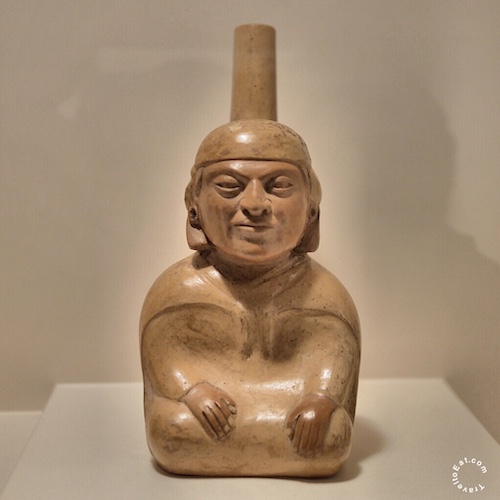

I was at the Larco Museum in Lima, Peru and saw these beautiful ceramics and pots, which inspired me to research this interesting and influential culture. The Moche civilization (alternatively, the Mochica culture, Early Chimu, Pre-Chimu, Proto-Chimu, etc.) flourished in northern Peru with its capital near present-day Moche and Trujillo, from about 100 AD to 800 AD, during the Regional Development Epoch. While this issue is the subject of some debate, many scholars contend that the Moche were not politically organized as a monolithic empire or state. Rather, they were likely a group of autonomous polities that shared a common elite culture, as seen in the rich iconography and monumental architecture that survive today. Moche history may be broadly divided into three periods: the emergence of the Moche culture in Early Moche (100–300 AD), its expansion and florescence during Middle Moche (300–600 AD), and the urban nucleation and subsequent collapse in Late Moche (500–750 AD). Moche portrait vessels are ceramic vessels featuring highly individualized and naturalistic representations of human faces that are unique to the Moche culture of Peru. These portrait vessels are some of the few realistic portrayals of humans found in the Precolumbian Americas.

One particularly famous Moche portrait vessel is known as the Huaco Retrato Mochica, seen above. The portrait was made during the Late Moche period (ca. 600 CE), according to the chronology made by Rafael Larco Hoyle in 1948. The ceramic portrait is also an example of a stirrup spout vessel of a Moche ruler. The ruler is depicted wearing a material turban on which there is a headdress decorated by a two-headed bird with feathers on side. The effigy also wears tubular earrings that can be found in the “Gold and Silver Gallery” of the Larco Museum. The exact archaeological context in which it was found in is unknown. Nonetheless, information gained from various archaeological discoveries in the North Coast over the past 20 years suggests that it belonged to the tomb of a member of the Moche elite. Archaeologists found this type of headdress, made of reed, in the tomb of the warrior priest god in the Huaca de la Cruz, an archaeological site situated in the Virú Valley, 40 km (25 mi) south of Trujillo, explored by Strong and Evans in 1940. It may also have been excavated from within the Moche Valley in the southern Moche region. Rafael Larco Hoyle received this piece from his father, Rafael Larco Herrera. It is said that this was the only ceramic piece Herrera kept when he bequeathed his private collection to the Museo del Prado in Madrid, Spain and that Herrera gave it to his son who later opened his private collection to the public at the Larco Museum.

Fine pottery vessels were usually made using molds, but each was individually and distinctively decorated, typically using cream, reds, and browns. Perhaps the most famous vessels are the highly realistic portrait stirrup-spouted pots. These are considered portraits of real people, and several examples could be made depicting the same individual. Originally these were considered grave goods but evidence of wear, chips and repairs have revised this opinion. Vessels decorated with religious themes were not merely indicators of social status at the site of Moche. They were strategically used at a household level, as tools to further political ambitions and communicate membership within groups. As evidenced by their iconographic content and the location in which they were abandoned, decorated vessels were an integral part of household-level rituals, meetings, and other status-building activities like feasts, where they were displayed, used, accidentally broken, and in some cases given away along with food and corn beer. It appears that there was a lot of independent development among these various Moche centres (except the eastern regions). They all likely had ruling dynasties of their own, related to each other. Centralized control of the whole Moche area may have taken place from time to time, but appears infrequent.

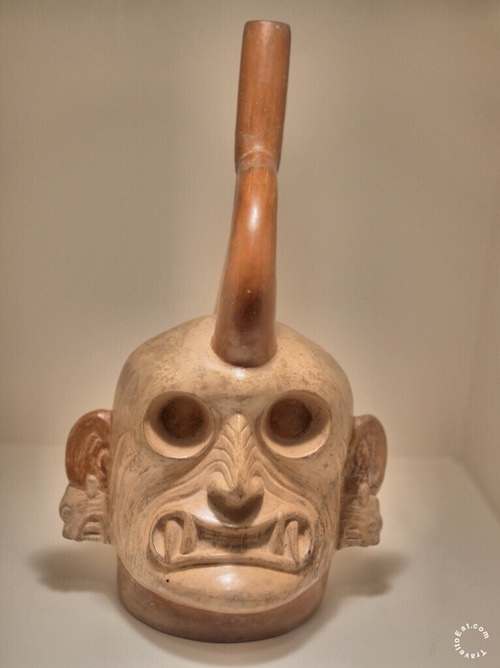

Moche religion and art were initially influenced by the earlier Chavin culture (900 – 200 BCE) and in the final stages by the Chimú culture. Knowledge of the Moche pantheon of gods is sketchy, but we do know of Al Paec the creator or sky god (or his son) and Si the moon goddess. Al Paec, typically depicted in Moche art with ferocious fangs, a jaguar headdress, and snake earrings, was considered to dwell in the high mountains. Human sacrifices, especially of war prisoners but also Moche citizens, were offered to appease him, and their blood was offered in ritual goblets. Both iconography and the finds of human skeletons in ritual contexts seem to indicate that human sacrifice played a significant part in Moche religious practices. These rites appear to have involved the elite as key actors in a spectacle of costumed participants, monumental settings and possibly the ritual consumption of blood. The tumi was a crescent-shaped metal knife used in sacrifices.

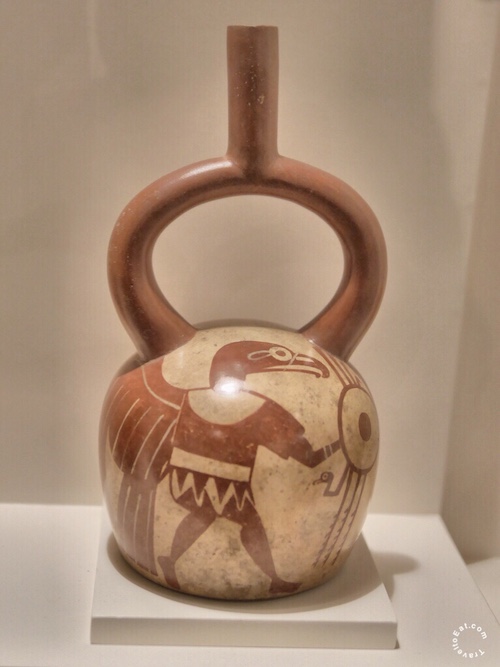

Moche iconography features a figure which scholars have nicknamed the “Decapitator”; it is frequently depicted as a spider, but sometimes as a winged creature or a sea monster: together all three features symbolize land, water and air. When the body is included, the figure is usually shown with one arm holding a knife and another holding a severed head by the hair; it has also been depicted as “a human figure with a tiger’s mouth and snarling fangs”. The “Decapitator” is thought to have figured prominently in the beliefs surrounding the practice of sacrifice.

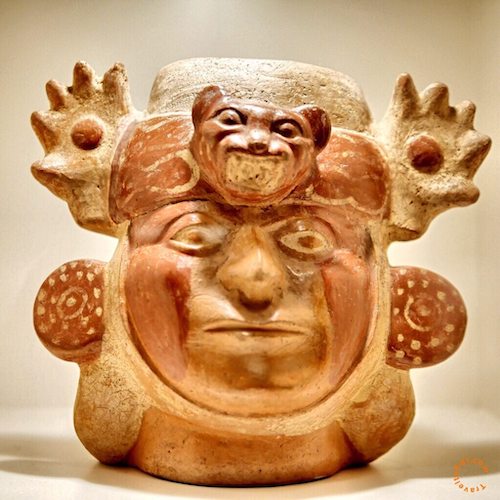

Moche society was agriculturally based, with a significant level of investment in the construction of a network of irrigation canals for the diversion of river water to supply their crops. Their culture was sophisticated; and their artifacts express their lives, with detailed scenes of hunting, fishing, fighting, sacrifice, sexual encounters and elaborate ceremonies. Because irrigation was the source of wealth and foundation of the empire, the Moche culture emphasized the importance of circulation and flow. Si was considered the supreme deity, as it was this goddess that controlled the seasons and storms that had such an influence on agriculture and daily life. In addition, the moon was considered even more powerful than the sun because Si could be seen both at night and during the day. This sculptural pitcher representing a Moche lord wearing face paint and adorned with earrings and a breastplate, standing beneath an arch formed by the body of a two-headed serpent. The two-headed serpent is a symbolic representation of the heavenly arch, and it is connected to the pitcher and to the body of a lord, who may represent an ancestral being associated with water. Although I have no proof, I believe this object may be associated with the worship of Si due to the reference to the heavens and water.

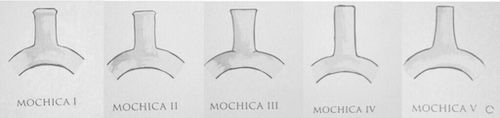

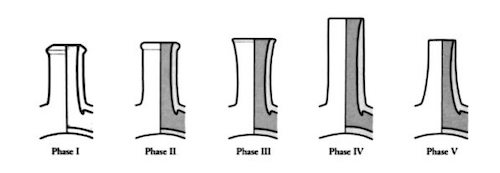

Moche is fairly well defined temporally, although its origins are less clear

than its demise. For many years, the foundation of Moche chronology was a five-phase ceramic temporal seriation of Moche-style vessels established by Larco Hoyle (1946, 1948). These phases were verified by archeological strata. Only recently has a closer look been taken at contemporary variation in ceramic styles within the Moche era and its potential significance for cultural dynamics. Larco Hoyle (2001 [1938/1939]), however, named the culture “Mochica,” on the presumption that the earlier style was made by the original speakers of the Muchik language. The members of the Moche Valley Project, with ties to the perspective of John Rowe used “Moche” following archaeological nomenclature procedures by naming the culture after a geographical feature, in this case, the river valley, in which the type site is located. While most scholars adopted this term, recently, some (Shimada, 1994) have returned to the former “Mochica.” If both “Moche” and “Mochica” derive from Muchik, then it might be claimed that which term one chooses matters little except for the needs of consistency. “Mochica” does seem to carry the sense of referring to an ethnic group and ongoing tradition, however, while “Moche” seems more objectively distanced with its link to the contemporary term for the valley and river. There is not enough data at this time, the five Larco phases are judged to have lasted between 100-200 years.

Larco Hoyle Mochica Phase One ceramics have a spout with a pronounced lip.

In Larco Hoyle Mochica Phase Two ceramics the spout has a less pronounced lip.

In Larco Hoyle Mochica Phase Three ceramics the spout has no lip and a flared opening.

In Larco Hoyle Mochica Phase Four ceramics the spout has no lip and a straight spout.

In Larco Hoyle Mochica Phase Five ceramics the spout has no lip and a triangular spout.

These tiny differences in the design of the spout may seem insignificant but Rafael Larco Hoyle spent his life investigating these features, scholarly study that has survived to the current day. While his studies may be underappreciated today, his insight into the history of Peru is indisputed. Scientists have found evidence of El Nino flooding at almost every Moche ceremonial center, but they are still not sure if mother nature is what brought this civilization to an abrupt end. They do know that Pampa Grande was abandoned in a hurry. Its occupants torching the city on their way out. There have been many comparisons between the Maya and the Moche cultures. The Olmecs created one of the first great civilizations in what historians call Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America), around the coast of the Gulf of Mexico from about 1400 to 300 BC. They built pyramid temples and played a ball game, later adopted by both the Maya and the Aztecs. The collapse of the Olmec state in Central America, about 400 BC, seems to have opened the way for other people to develop states of their own. The Moche and Maya were some of these kingdoms. The Maya flourished from 300 BC to 900 CE and the Moche flourished from around 1 CE to 800 CE. There must have been communications between these two great civilizations. I am going to stop here, although we will revisit this subject. As always please leave a comment.

[mappress mapid=”164″]

References:

Met Museum: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/moch/hd_moch.htm

Ancient History: http://www.ancient.eu/Moche_Civilization/

Harvard: https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/files/docs/moche_chapter1.pdf

Jeffrey Quilter: http://www.geos.ed.ac.uk/~nabo/meetings/glthec/materials/quilter/Quilter_MochePolReligWar.pdf

Moche: http://mayaincaaztec.com/moci.html

Parallels Between Moche and Maya: http://www.angelfire.com/zine/meso/meso/mochemaya.txt

Americas before the Maya and Moche: http://www.waa.ox.ac.uk/XDB/tours/americas.pdf