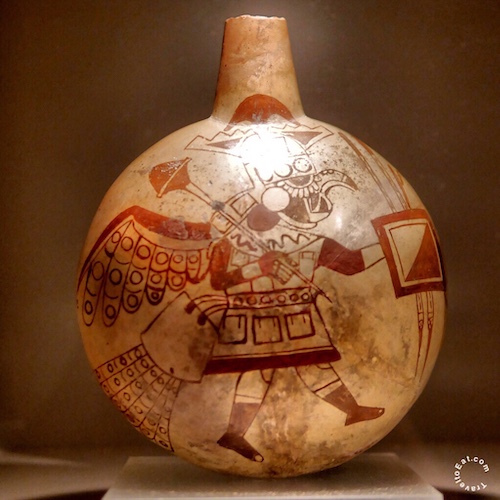

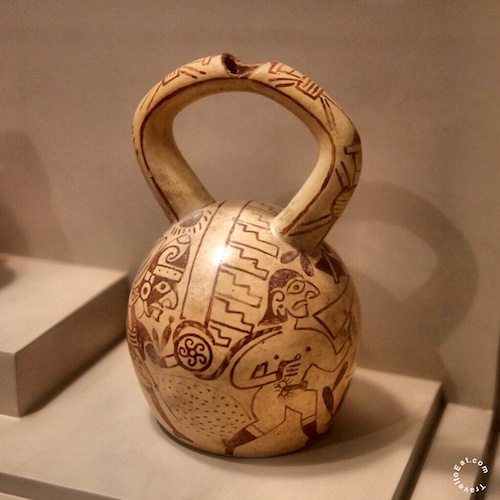

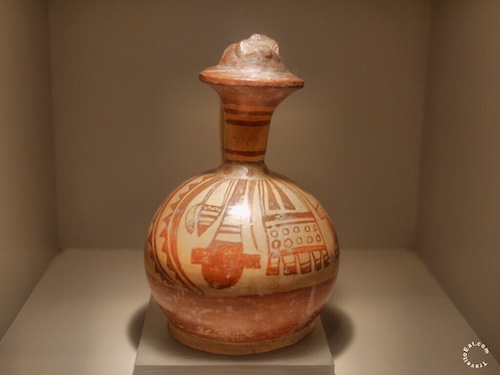

At the Larco museum they had a section devoted to Moche warfare and ceremonial human sacrifice. Flourishing on the north coast of Peru between 100 and 800 CE, the Moche created ceramic vessels richly decorated with detailed, fineline paintings that relate complex tales. The surviving ceramics provide a wealth of information about Moche society and iconography. Moche artists frequently depicted warriors and warrior activities, and hundreds of these depictions can be found in museums and private collections today. The combat they depict appears to be ceremonial rather than militaristic. There are no depictions of warriors attacking castles or fortified settlements, or killing, capturing, or mistreating women or children. Moreover, there is no portrayal of equipment or tactics that involved teams of warriors acting in close coordination. We see no regular formations of troops like Greek phalanxes, or siege instruments whose operation would have involved trained squads of individuals. Although there are a few depictions of two warriors fighting a single opponent, the essence of Moche combat appears to have been the expression of individual valor, in which the warriors engage in one-on-one combat. Only rarely were combatants killed; the goal appears to have been to capture the opponent for ritual sacrifice.

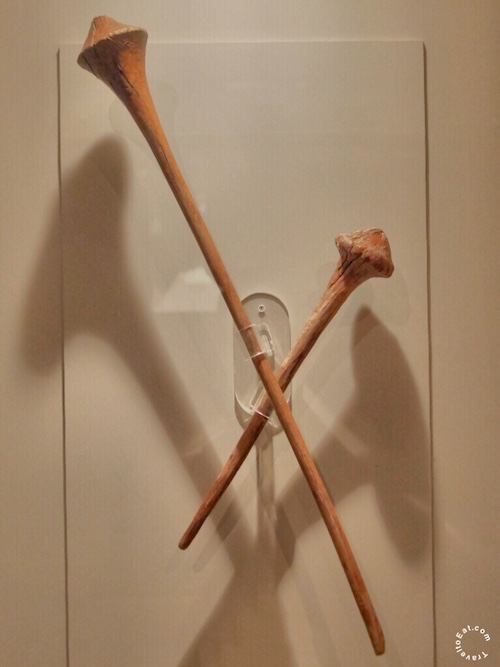

Two distinct regions of the Moche civilization have been identified, Southern and Northern Moche, with each area probably corresponding to a different political entity. Clubs seem to have the preferred weapon in Moche society. The Moche may have also held and tortured the victims for several weeks before sacrificing them, with the intent of deliberately drawing blood. Verano believes that some parts of the victim may have been eaten as well in ritual cannibalism. The sacrifices may have been associated with rites of ancestral renewal and agricultural fertility.

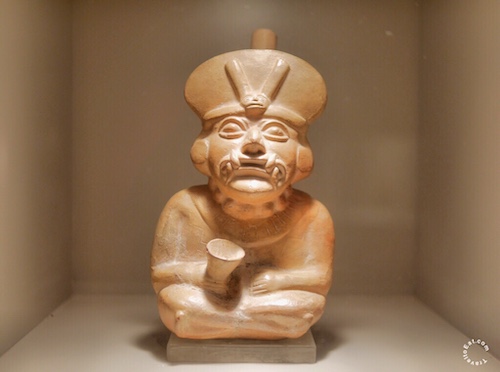

Both iconography and the finds of human skeletons in ritual contexts seem to indicate that human sacrifice played a significant part in Moche religious practices. These rites appear to have involved the elite as key actors in a spectacle of costumed participants, monumental settings and possibly the ritual consumption of blood. As you can see in the above warriors, they appear to have crowns and earrings suggestive of the elite class.

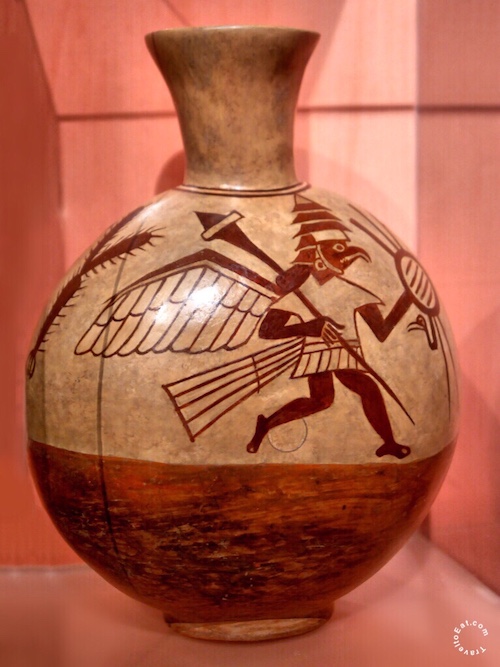

In Andean religion, winged and armed gods have existed since ancient times. Here we can see winged warriors as a representation of bird warriors in Moche art.

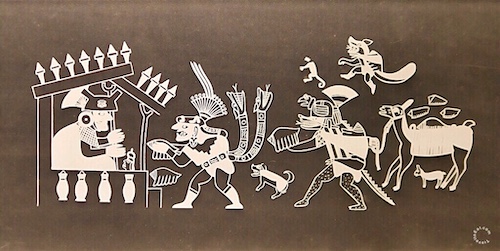

Moche warriors faced each other with clubs and shields. Combat was hand-to-hand and seems to have taken place in open areas or plazas created for this purpose. When a warrior removed another’s helmet or grabbed his hair the combat was over. The defeated warrior was stripped and his weapons and clothes were wrapped in a bundle. The victors led the defeated warriors by ropes tied around their necks to their final destination, the place of sacrifice. Those who argue that warfare was ritual advance several points for their position. Bourget (2001, p. 94) notes the fragility of shields and clubs, inad- equate for real combat but consistently shown in art, while other weapons of war (slings and lances) are depicted less frequently. Furthermore, most depictions of combat show Moche versus Moche (judging by costumes), instead of Moche fighting against foreigners (Bourget, 2001, p. 94). Bourget recognizes that real warfare may have taken place; his point is that what is depicted in the art is a form of ritualized combat designed to provide prisoners for sacrifice.

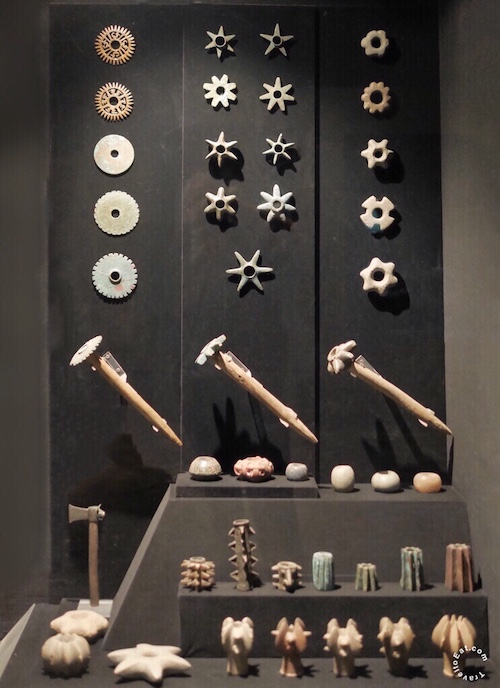

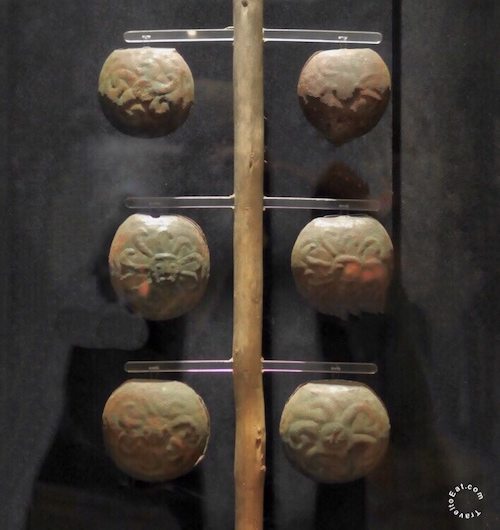

Apparently music was an important part of the ceremony, providing a heightened sense of drama to the combat. Seen above are musicians playing a drum and flute. There were many other musical instruments which can be seen below.

The quena is the traditional and yet modern flute of the Andes. Traditionally made of totora wood, it has 6 finger holes and one thumb hole, and is open on both ends or the bottom is half-closed (choked). Although these Moche ceramic flutes have almost identical features they only have 4 finger holes.

The so-called Indian Flute, also as panpipes, is a typical Andean musical instrument and to this day it forms one of the most important elements of Peruvian folkloric music. ln ancient Peru this instrument was played in ceremonies in Moche deplctions of the dance of the dead or scenes associated with the underworld, musicians play the panpipes before a confrontation. This instrument is played on pairs, reinforcing the sense of a search for contact between opposites.

In any large public ceremony you almost have to have a trumpet and the Moche relied on the tropical mollusk Strombus, used in the Andes as a ceremonial trumpet, and known as a pututo. The Strombus is a warm water seashell associated with the cycle of water. Water originates in the sea and then returns to the earth as rainfall, and via rivers and canals it irrigates the land and causes plants to flourish. Pututos, which produce a strong deep sound, were played by trumpeters in ceremonies associated with water. Strombus shells were also Important offerings to the gods, who had to be thanked for the blessings theybestowed. That is why they are found In groups of offerings placed in important temples, beginning during the Formative Epoch. In ancient Peru ceramic trumpets were also made, and their designs recreated the shape of these seashells.

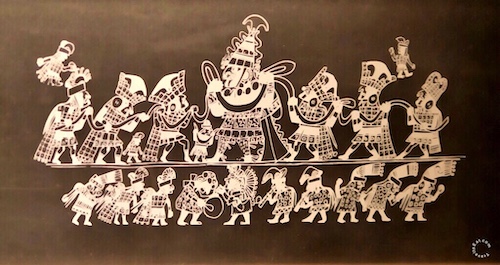

The “Dance with a Rope” was a ceremony in which warrior chiefs participated dressed in their finest clothing and personal adornments. This was a celebration associated with ritual combat and sacrifice. This dance has been represented in the art of a number of cultures of ancient Peru, from the Moche to the Incas. In the “Dance of the Rope” depicted in Moche art, the main protagonist wears the clothing of a warrior chief, with a conical helmet and coccyx protector. He also possesses the teeth of a feline, in a clear allusion to his supernatural character. This supernatural warrior appears at the center of the ceremony holding a rope, while two groups of warriors can be seen at his sides wearing their own ceremonialy clothing. Some of the warriors wear shirts decorated with square plaques, while others wear shirts adorned with circular metal decorations. Musicians playing a drum and flute accompany the dancers in the ritual.

Ceremonial shirts were important symbols of power and status. The most elaborate examples feature plaques made from precious metals which would shine and rattle as the wearer moved. These shirts were also used to clothe the rulers after death. Gilded discs were incorporated into several types of ornaments from an early date. Crowns, shirts and other personal adornments featured discs, as we can see in Vicus art, and very often in the art of the Moche culture.

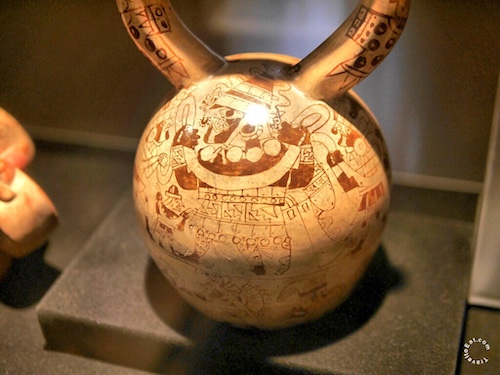

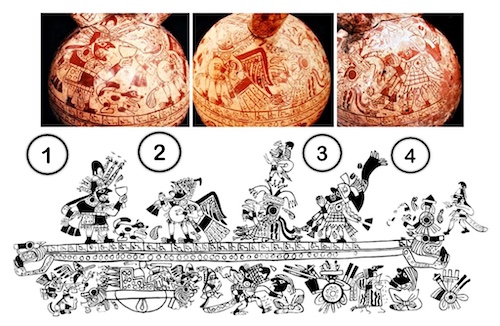

Perhaps the most reproduced and discussed Moche ceramic paintings is the stirrup spout vessel at the Museum für Völkerkunde in Munich. Originally called the Presentation Theme, it is now known as the Sacrifice Ceremony. The Rayed Deity (1), now called the Warrior Priest. (2) Owl Deity or Priest. (3) The Woman, now called The Priestess. (4) A figure with a plaque shirt. The top scene depicts the presentation of a goblet of blood. The bottom scene depicts prisoner sacrifice. This is a relatively complete summery of the process of Moche human sacrifice.

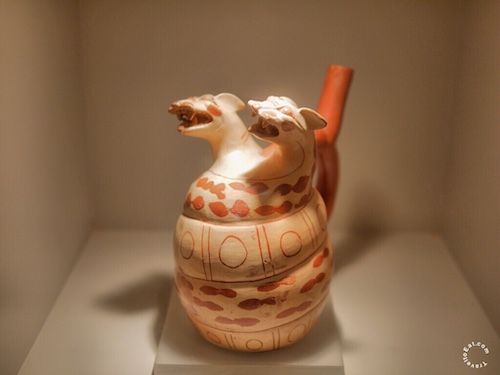

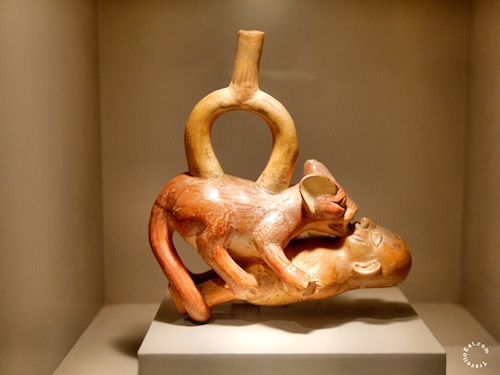

One might well ask what is the significance of this dog in Moche theology. The short answer is that we do not know, this dog appears in multiple instances as a pet of the Sun God or Radiant God. Of slightly more interest is what kind of dog this is. When and where dogs were first domesticated has vexed geneticists for the past 20 years and archaeologists for many decades longer. All dogs alive today can trace at least some of their ancestry back to dogs that were domesticated 33,000 years ago in southern East Asia, suggests one of the most extensive ever investigations of canine DNA. The genome-wide phylogenetic tree indicated a genetic divergence between New World and Old World wolves, which was then followed by a divergence between the dog and Old World wolves 27,000-29,000 YBP. The dog forms a sister taxon with Eurasian gray wolves but not North American wolves. Thus when our first American ancestors crossed the Berring Bridge, they brought their dogs with them. The Peruvian Hairless Dog is a breed of dog with its origins in Peruvian pre-Inca cultures. It is one of several breeds of hairless dog. Ceramic hairless dogs from the Chimú, Moche, and Vicus culture are well known. Depictions of Peruvian hairless dogs appear around 750 A.D. on Moche ceramic vessels and continue in later Andean ceramic traditions.

This depiction of a combatant being carried in a litter either before or after a successful combat gives us clues to the theatrical ceremony as a whole.

The Tumi is a ceremonial knife used by ancient Peruvian cultures as a means to perform sacrifices. It consists of two parts, a semi-circular blade and a handle often representing the northern Peruvian God Naymlap. In Moche art the gods were represented fighting among themselves, or against other supernatural beings or humans. These battles ended with the decapitation of the defeated opponent. The gods are represented holding a half-moon shaped knife known as a tumi. The best known Tumi knives have been found in archeological sites in the north coast of Peru, especially those made by the Lambayeque culture also known as Sipan. However, they were not exclusively used by them as they have also been found in archeological sites that belong to the Moche, Chimus and later the Incas. The rattle Timu began with the Vicus Culture. Moche and Vicús iconography depicts warriors with one or more of these instruments tied to their belts, hanging downwards, probably to add to the terrifying sound of their battles.

Moche iconography features a figure which scholars have nicknamed the “Decapitator”; it is frequently depicted as a spider, but sometimes as a winged creature or a sea monster. Together all three features symbolize land, water and air. When the body is included, the figure is usually shown with one arm holding a knife and another holding a severed head by the hair, it has also been depicted as “a human figure with a tiger’s mouth and snarling fangs”. The “Decapitator” is thought to have figured prominently in the beliefs surrounding the practice of sacrifice.

Moche art illustrates other ways in which defeated warriors were sacrificed. Some ceremonies occurred on islands, with the warriors transported on rafts. Another type of sacrifice took place in the mountains, and the warriors were thrown off a precipice.

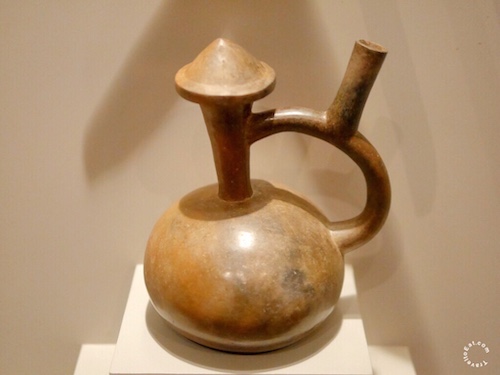

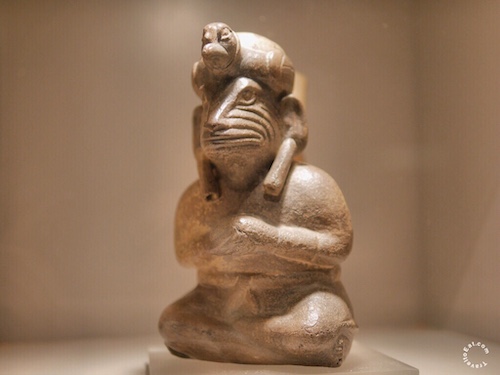

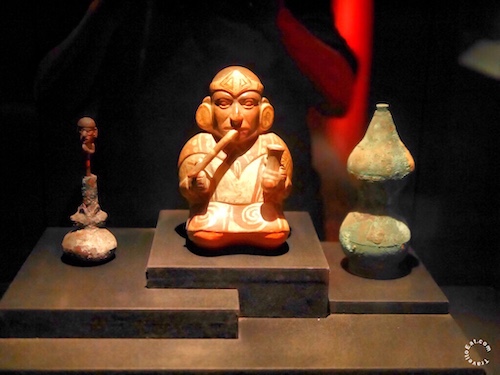

Although there are no specific depictions, it is more than likely that the audience to these ceremonies were chewing the cocoa leaf. The ceremonial chewing of coca leaves has been practiced in the Andes since ancient times. These containers contained the lime with which the coca leaves were mixed. The lime was extracted using a stick which was then placed in the mouth of the person chewing the leaves, where it acted as a catalyst in the extraction of the alkaloid components of the cocoa leaf. As always, please leave a comment.

[mappress mapid=”167″]

References:

Fineline Moche Drawings: http://www.doaks.org/resources/online-exhibits/capturing-warfare/moche-depictions-of-warfare

Moche Politics, Religion and Warfare: https://www.academia.edu/4231357/Moche_Politics_Religion_and_Warfare

Moche: http://archive.archaeology.org/0203/abstracts/moche.html

Dogs, Gods and Monsters: http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/11/14/1068674374387.html?from=storyrhs

First Domesticated Dogs: https://www.nytimes.com/books/first/s/schwartz-dog.html

Domesticated Dogs: http://news.discovery.com/animals/pets/dna-dates-dog-domestication-back-33000-years-151215.htm

Peruvian Inca Orchid Dog: http://www.vetstreet.com/dogs/peruvian-inca-orchid