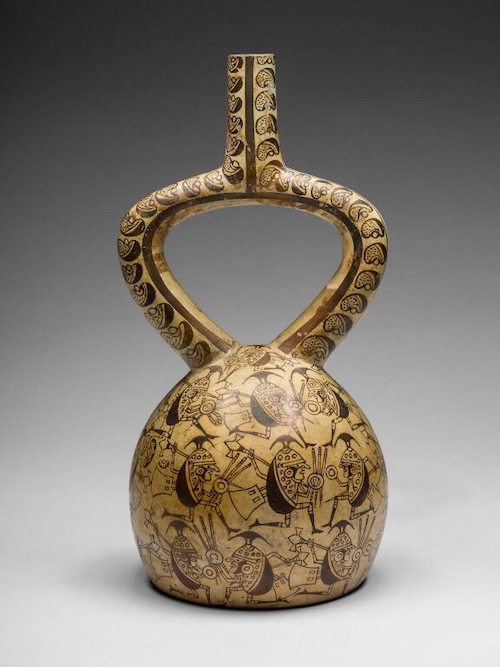

Two of the most common recurring themes on Moche/Mochica culture pottery are depictions of anthropomorphic birds, animals and lima beans. These themes played prominent roles in ceremonies and everyday life. Birds were precious resources in the economy of Andean societies. Merchants traded brilliantly colored parrot and macaw feathers in long-distance networks connecting the Amazonian rainforest, the Cordillera, and the remote Pacific coast, where they decorated garments of rulers and kings. Coastal agriculturalists used guano to enrich their fields. Sailors collected the valuable fertilizer offshore on sacred islands, where they left prestigious offerings. On the coast, domesticated muscovy ducks may have been part of the subsistence. One of the frequently recurring themes in Moche art is the race between human beings with the features of animals, carrying bags with lima beans and sticks in their hands. In this race the runners participated wearing their finest clothing and elaborate headdresses, one of the most characteristic of which was the circular frontal headdress.

Bird and Bean Runners

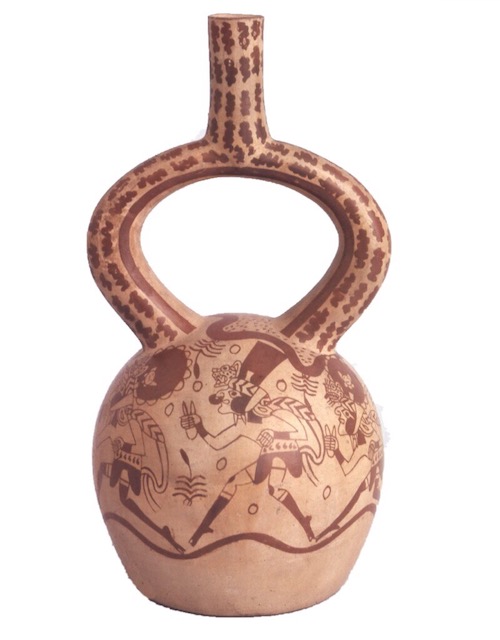

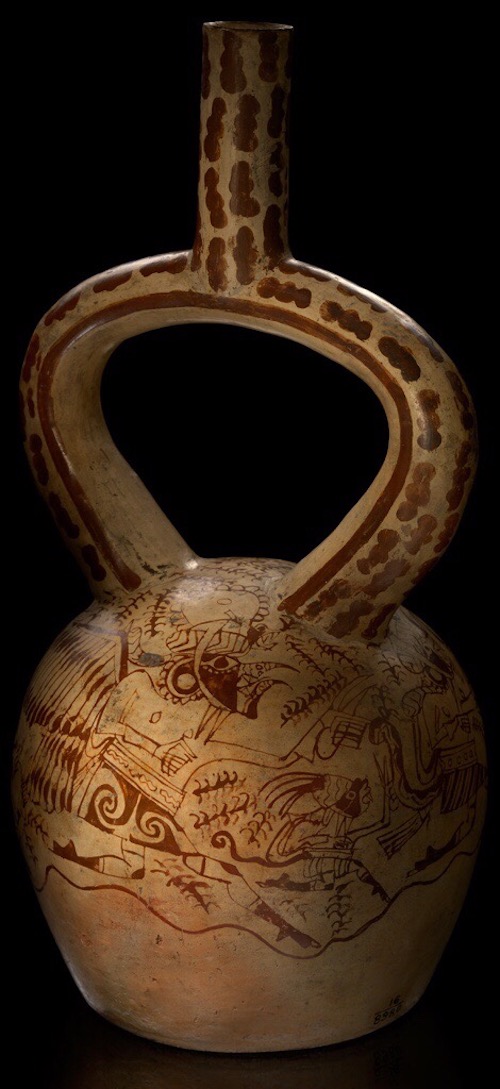

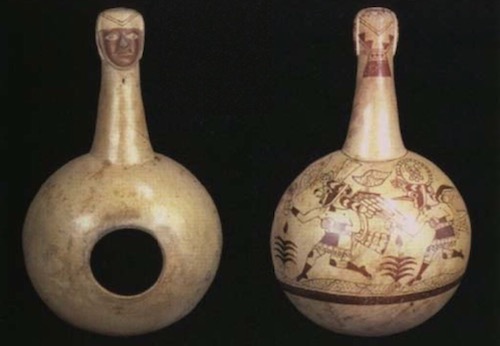

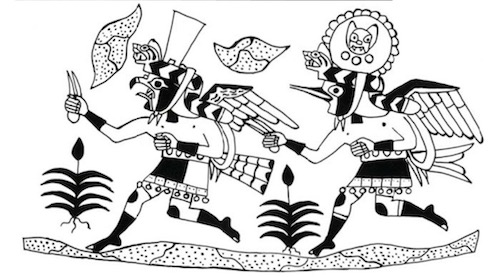

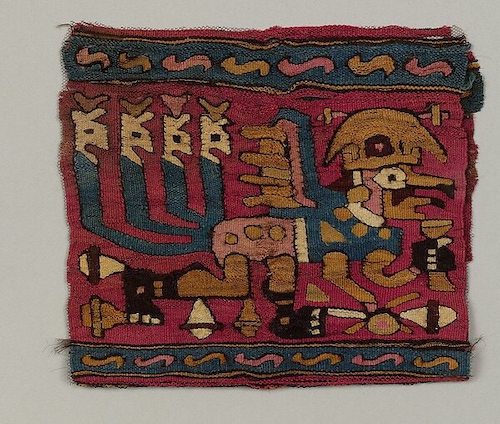

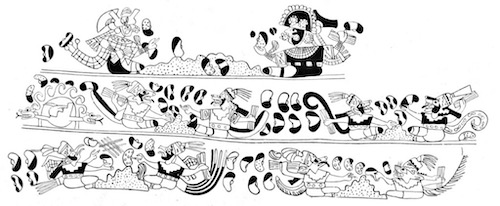

Men running in line through a sandy landscape, each carrying a bag or folded cloth, constitute a common subject of Moche phase IV fine line ceramics. They carry no weapons and lack warrior dress; they wear a loincloth or kilt but no shirt or tunic. They are most often depicted as a human body with the head of a bird or animal. The typical runner headdress has the head of an animal, usually a fox or feline, in front of a vertical plaque. Headdress plaques usually alternate round and trapezoidal shapes. This headdress can appear along as a ceramic motif. All carry a bag of folded cloth presumably full of Lima beans.

The painting on this stirrup-spout vessel represents a procession of ritual runners in the form of humanized animals, including a warrior with the face, wings, and tail of a bird, perhaps a hawk. The warrior figure is wearing the typical Moche warrior’s skirt, belted at the waist. Warriors are often associated with hawks in Moche art.

Each of these examples of “Bird Runners” share the same common characteristics. Each carries a bag of beans, loincloth or kilt but no shirt or tunic, no weapons, fox headdress and alternating round and trapezoidal crowns. The fact that these runners are predominantly human in bird form has a not so hidden meaning. Birds are swift, moving from location to location quickly, a natural choice for ceremonial runners. The choice of a winged messenger is echoed in ancient Greece and Rome in the personae of Hermes and Mercury respectively. Hermes is considered a god of transitions and boundaries. He is described as quick and cunning, moving freely between the worlds of the mortal and divine. He is also portrayed as an emissary and messenger of the gods.

Bird Runner Jewelry

The same themes can be found on jewelry as in these two sets of ear ornaments. On these pairs of ear ornaments, bird-headed winged runners, worked in turquoise, sodalite, and spondylus shell, hold bags (probably full of lima beans) in their outstretched hands. Their eyes and beaks are sheathed in gold.

Owls in Moche Culture

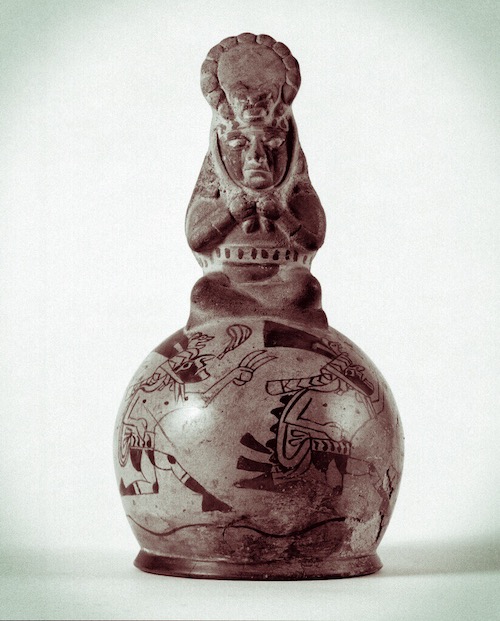

Several species of owl can be identified in Mochica art and pottery, including the barn owl, typical owl, burring owl, and speckled owl. The Mochica owl symbolism seems to hold various meanings. In Moche folklore the owl represented the spirits of the dead, the intermediate, and even a powerful figure. Owls played a significant role in Moche religion. In art, they carry defeated warriors to the world of the dead, as they would carry their catch to the nest. The bird priest or owl deity was depicted over and over again as one of the chief figures in the ceremonial sacrifices the Mochica have been linked to. It is also argued because of the number of owls buried in the forms of jewelry, staffs, pottery, and paintings that the owl is an intermediated to help the dead to reach the underworld or afterlife. The owl warrior and sacrificer may be one God or two. The concept of decapitation seems to be pan-Andean in scope, and on the north coast of Peru during Cupisnique and Moche times the concept was codified as a theme. While there are examples of monster, fish and spider Decapitators, the single example of the supernatural owl decapitater pictured here is a modeled and painted ceramic bottle. It clutches a Tumi (a knife used in human sacrifice) in one hand and a disembodied human head in the other. Of interest in this example are the combination of an owl, large ears with earnings and fangs of a feline.

The Fox in Moche Culture

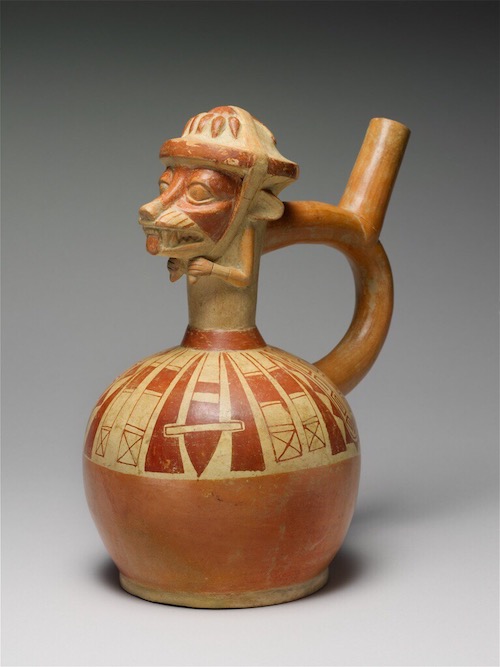

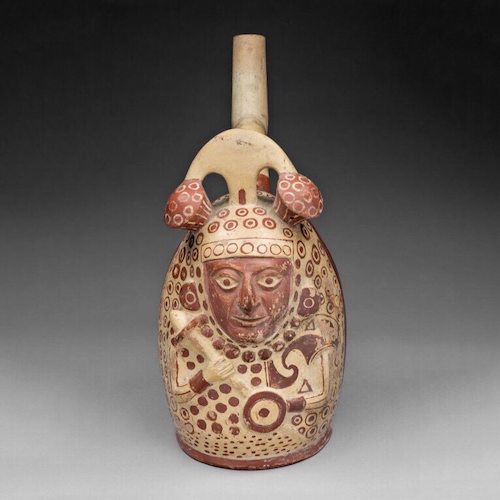

This stirrup spout bottle shows Moche warrior attributes represented in two and three dimensions. Clubs, lances, and helmet strings painted in red radiate from the center of the vessel’s body. On top of the bottle, the tridimensional part can be interpreted as a fox warrior tying a club-shaped headdress under its chin. Fruits or tubers appear on the front of the headdress. Foxes are often depicted as warriors in Moche art. Their role in religion perhaps derives from their behavior in the natural world. Foxes hunt and capture small prey, as warriors would fight and capture prisoners. As foxes are nocturnal and live in underground burrows, they are also associated with the world of the dead.

Felines in Moche Culture

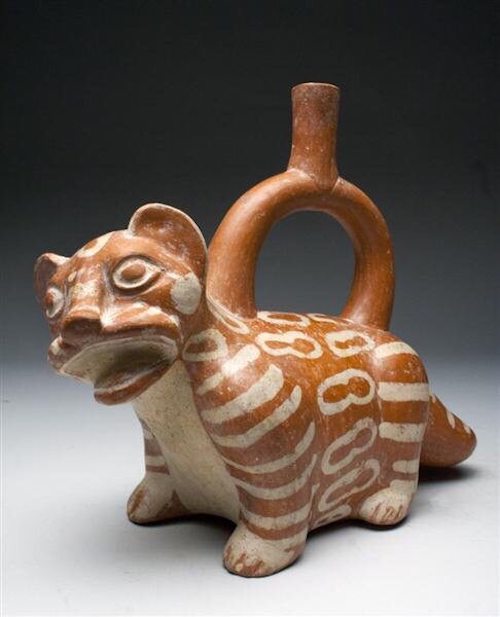

Many of these “Bird Warriors” are depicted with a feline pelt in addition to other ornaments. Unlike other parts of Peru, where jaguars were common, the Moche lived in a region where there were smaller felines. While they sometimes portrayed jaguar cubs, they were more likely to depict ocelots, margays, Pampas cats or jaguarondis. Pumas also feature in the art of highland cultures. The creatures all display the same hunting prowess, poise, stealth and aggression that appealed to warrior cultures such as the Moche. Felines were associated symbolically with military, religious and political leaders. The tombs of the elite were often filled with feline imagery, and it was also incorporated into their textiles, jewellery and other adornments. The Moche ruler known as the Lord of Sipán, whose tomb was discovered in Lambayeque Valley in northern Peru, was buried with objects emblazoned with various cat motifs. Of the feline faces found in the Sipán tombs, some were depicted with open mouths full of inlaid-shell fangs and teeth, creating a particularly ferocious image. Adorned with this type of ornamentation, it was believed that the wearer became the animal or gained its power. Cats might have also represented ancestors or humans gone to the afterlife.

Lima Bean Bags

Lima beans were probably used by the Moche on the northern coastal Peru as carriers of meaningful information, whose surface was fashioned in a rich variety of patterns. The raw material was lima beans, a familiar agricultural produce used since pre-historic times in Peru, not the ordinary or kidney beans (Phaseolus vulgaris). Lima beans have had a long history in South America, with remains of beans dating to around 6000 BC. While there are several different types of Lima beans that grow across Central and South America, the Moche people would have consumed the denser variety of bean that is familiar in most grocery stores today. Lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus) offered a fairly large flat and smooth surface, appropriate for drawing and incision. The vessels’ pictorial strips, and archaeological findings, show us that storage and transport were done in small, handy leather pouches apparently made from the tanned hide of llamas or cloth bags made from llama or alpaca wool.

Lima Bean Tokens

Sixty-eight years ago, Rafael Larco Hoyle identified more than 300 different types of painted lima beans in the pictography of Mochica vases. In the figures above are some of the patterns painted on lima beans which he identified in the 1940’s. I have included an excellent paper reviewing the possible meaning of these markings by Tomi S. Melka but unfortunately at this time the true meaning of these markings remains elusive. It is clear however that these were used as tokens, a recording system understood by both sender and recipients, carried from village to far flung village by runners. Rafael Larco Hoyle himself made analogies between the marked Lima beans and Maya script although modern authors are more cautious regarding this comparison.

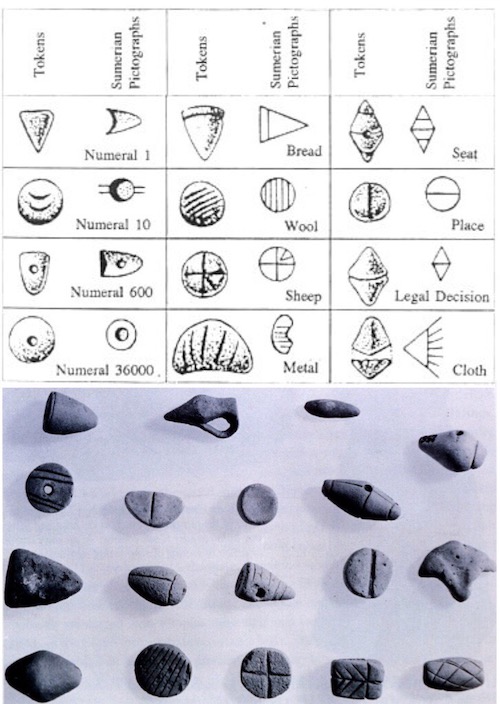

The earliest known writing for record keeping evolved from a system of counting using small clay tokens. The earliest tokens now known are those from two sites in the Zagros region of Iran: Tepe Asiab and Ganj-i-Dareh Tepe from about 3500 BCE. This system evolved into the one of the earliest written languages, cuneiform. It is generally agreed that true writing of language (not only numbers) was invented independently in at least two places: Mesopotamia (specifically, ancient Sumer) around 3200 BC and Mesoamerica (Olmec culture) around 600 BC. It is interesting that this Lima painted bean system existed hundreds of years after the Olmec culture and coincident with Maya culture glyphs. Even more interesting is the use of a knot system of messages used by the Incas hundreds of years later.

Beans and Sticks Ceremony

This is a ceramic bottle depicting a mythological scene of Lima beans being deciphered. The scene is organized in three levels. At the top there are two mythological beings: one is an anthropomorphic personage with feline fangs and a headdress adorned with a semicircular element, the other is an anthropomorphic owl. Both are sitting on the side of a mound of sand, and are interacting with sticks and lima-beans with spots, in a kind of divination game. In the second level there are four zoomorphic personages (two foxes, a monkey, and a jaguar) who wear shirts with stepped designs. On the lower level of the scene there are another four zoomorphic personages (two birds, a deer and a squirrel). They are arranged in pairs facing each other, with a mound of sand between them, and are also interacting with the sticks they carry in their hands and lima-beans with spots. The scene seems to be referring to a mystical or divinatory ritual possibly in relation to future agricultural results.

Bean Warriors

As a final and somewhat strange depiction of beans in the Moche culture, there are the “bean warriors”. Honestly I have no good explanation of why the Moche would conceive of lima beans as warriors, in fact it is nothing short of hilarious. Perhaps the Moche culture had a good sense of humor. It is more likely that the Moche culture anthropomorphized many things important in their lives and lima beans were clearly important to the Moche. As always, I hope you found this post interesting, please take the time to leave a comment.

References:

Birds in the Andes: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bird/hd_bird.htm

Moche Ceramics: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/moch/hd_moch.htm

Iconography of Winged Figures: http://www.academia.edu/1079866/The_Iconography_of_Moche_Winged_Figures

Moche Owls: http://lmcarthur.weebly.com/uploads/4/9/0/0/4900041/mochica_pottery.doc

Moche Felines: http://nga.gov.au/exhibition/INCAS/Default.cfm?IRN=231267&MnuID=3&ViewID=2

Lord of Sipán: http://www.sungodperu.com/lord-of-sipan-machu-picchu/

Lima Bean Recording System: http://docplayer.net/3605480-The-moche-lima-beans-recording-system-revisited.html

Origin of Writing: https://www.usu.edu/markdamen/1320Hist&Civ/chapters/16TOKENS.htm