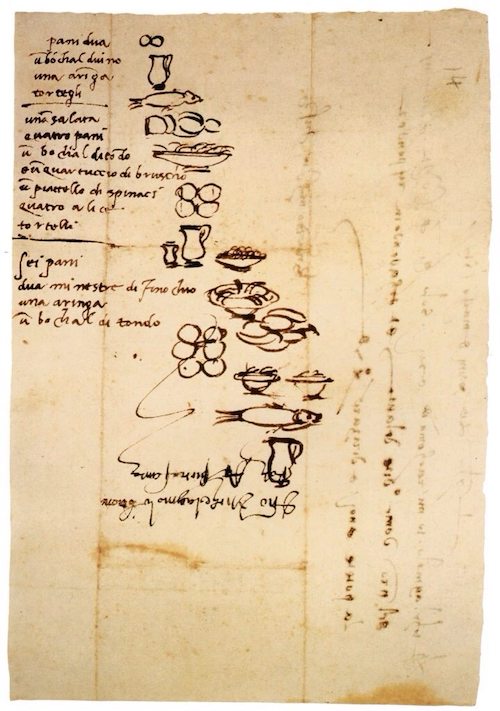

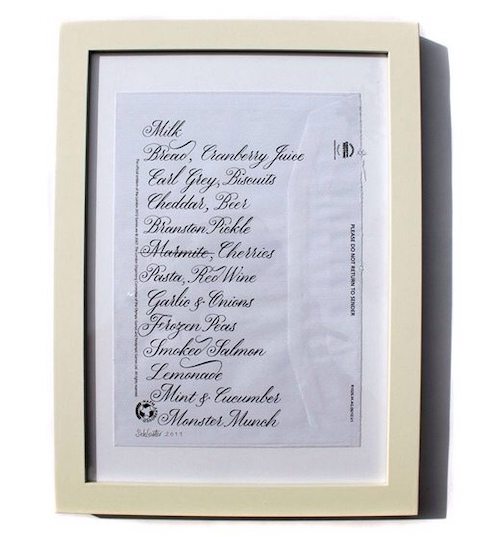

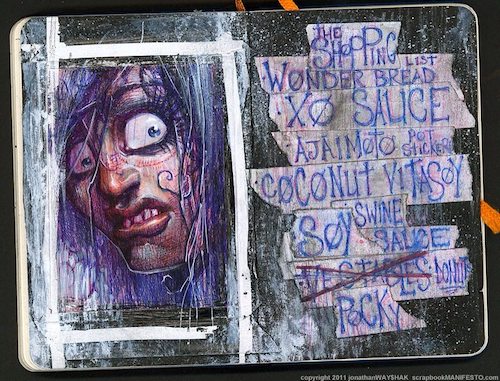

The other day I was searching the web for another purpose and came upon a shopping list by Michelangelo, which was part of an exhibition “Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane, Master Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti” at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in Spring of 2013. The exhibit included 26 drawings preserved in the artist’s family home, the Casa Buonarroti, in Florence. “Because the servant he was sending to market was illiterate”, writes the Oregonian‘s Steve Duin in a review of a Seattle Art Museum show, “Michelangelo illustrated the shopping lists – a herring, tortelli, two fennel soups, four anchovies and ‘a small quarter of a rough wine’ – with rushed (and all the more exquisite for it) caricatures in pen and ink.” As we can see, the true Renaissance Man didn’t just pursue a variety of interests, but applied his mastery equally to tasks exceptional and mundane. Which, of course, renders the mundane exceptional. This scrap of ephemeral paper from the past fascinates me, the detail of the little drawings is astounding. We compose ephemera every day in the form of disposable to-do lists, directions to unvisited destinations, notes to people we know or have never met, and shopping lists of this kind. This kind of writing powers our ordered experiences, as ephemeral texts chart encounters before being rendered useless. Collected, disposable shopping lists create an archive of everyday artifacts that we can peruse for traces of the everyday both past and present. I thought I would present a few more examples and explore the origins of writing such lists.

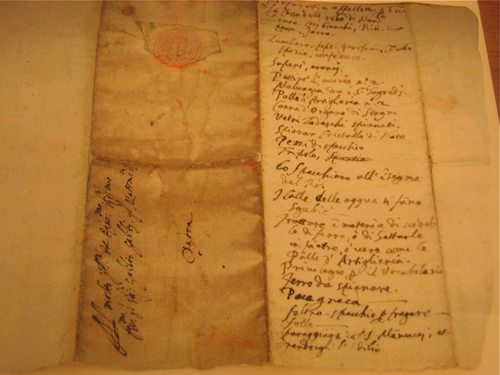

Here is a page from one of the famous astronomer Galileo’s notebooks on which he listed the supplies for a scientific experiment having to do with optics. Interspersed in that list he had scribbled words like chickpeas, rice, pepper and sugar, obviously grocery items he needed. Clearly he was hungry while he pondered the mysteries of astronomy.

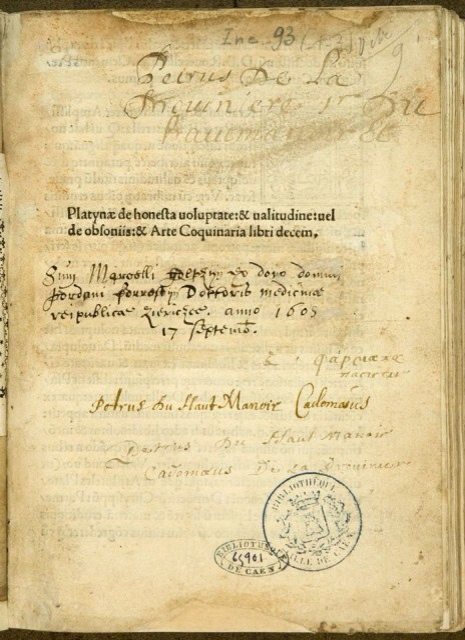

In his personal library collection, da Vinci owned a single cookbook, Platina’s On Right Pleasure and Good Health, which is considered to be the first printed cookbook (and one of the first printed books anywhere). First published in Rome in 1470, the book focuses heavily on the dietary advantages of various foods and how to prepare them. Nearly every recorded item in da Vinci’s larder (cold pantry) was included in Platina’s writings, including buttermilk, eggs, melon, grapes, mulberries, mushrooms, sorghum, flour, herbs, spices, beans, meat, sugar, vinegar and wine. (DeWitt, 114-122). Da Vinci’s personal notebooks are filled with comments on the cost and quality of the food and drink he encountered throughout Italy. For example, da Vinci noted that a bottle of wine, a pound of veal and a basket of eggs cost “one soldo” each. Also included in the notebooks were his shopping lists, which varied between elaborate ingredients for court feasts and rather simple items for his own household’s fare. He wrote daily in his notebooks in Italian, using “mercantile script” mirror writing, from right to left, not intended for others. He didn’t write linearly, in complete thoughts, or with logical progressions, but observationally.

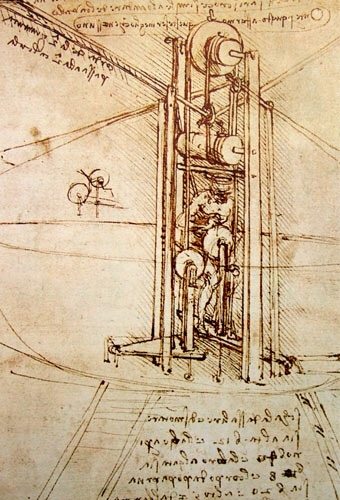

Da Vinci felt every kitchen task could be mechanized; crushing garlic, pulling spaghetti, plucking ducks or cutting a pig into cubes, but the machines Leonardo imagined were sometimes far more elaborate than the task required. His invention for a giant whisk twice the size of a man, seen above, involved an operator from within who was constantly in danger of being whisked into the sauce.

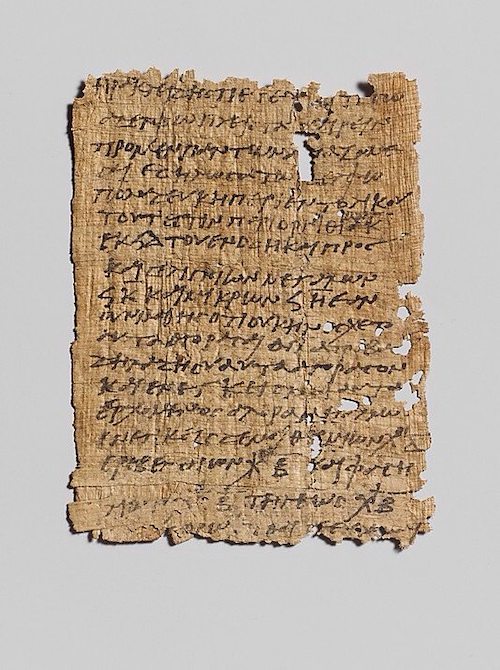

The papyrus shown above contains a letter written by Heraclides of Pontus, a Greek philosopher and astronomer who lived and died at Heraclea Pontica, to his brother Petechois. It is essentially a shopping list of items – poultry, bread, lupines, chick peas, kidney beans and fenugreek at various prices – that Heraclides wants Petechois to bring him. Such documents provide important evidence for the level of literacy in the Roman world and offer an insight into the everyday lives of ordinary people. As described by Keith Hopkins: “The Roman empire was bound together by writing. Literacy was both a social symbol and an integrative by-product of Roman government, economy and culture. The whole experience of living in the Roman empire, of being ruled by Romans, was determined by the existence of texts”. Even so, just to pull numbers out of a hat, I would say that the Roman Empire might have had a literacy rate around 10%, maybe 20% tops, and medieval Europe probably under 5% in the early Middle Ages, rising gradually to around 10-20% by the end of the 15th century.

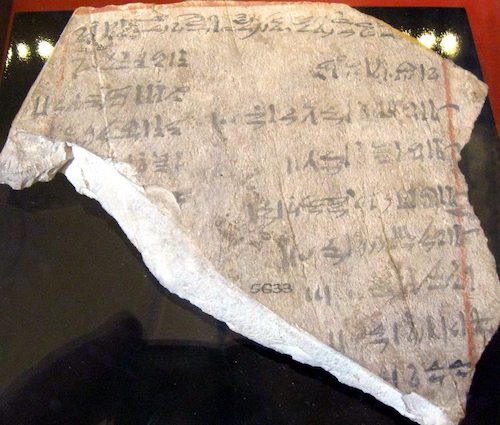

Deir el-Medina is an ancient Egyptian village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th dynasties of the New Kingdom period (ca. 1550–1080 BC). The nature of their work meant that nearly all the workers were literate and thus, the village was a lively place for ephemeral written notes. The settlement’s ancient name was “Set Maat” (translated as “The Place of Truth”), and the workmen who lived there were called “Servants in the Place of Truth”. During the Christian era the temple of Hathor was converted into a church from which the Arabic name Deir el-Medina (“the monastery of the town”) is derived. In archaeology, ostraca may contain scratched-in words or other forms of writing, which may give clues as to the time when the piece was in use. Generally discarded material, ostraca were cheap, readily available and therefore frequently used for writings of an ephemeral nature such as messages, prescriptions, receipts, students’ exercises and notes: pottery shards, limestone flakes, thin fragments of other stone types, etc., but limestone sherds, being flaky and of a lighter color, were most common. The image above shows a limestone ostracon containing the shopping list of a lady Webkhet in the 20th Egyptian Dynasty (1187-1064 BC) during the New Kingdom. It is about the size of a dinner plate and an inch thick. It is written in hieratic, a cursive form of hieroglyphics.

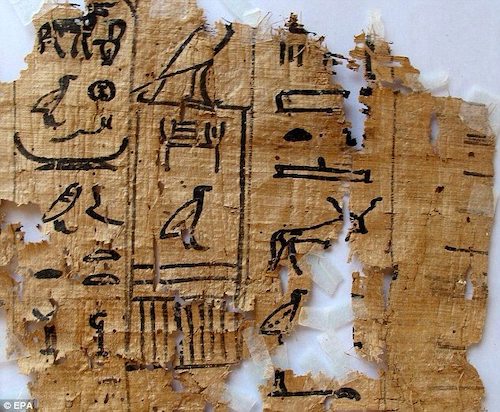

Archaeologists have stumbled upon what is thought to be the world’s oldest port. The harbor, discovered on the Red Sea coast, is believed to date back 4,500 years, to the days of the Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops) in the Fourth Dynasty (2613-2494 BC). Teams believe it was once one of the most important commercial ports of ancient Egypt, and would have been used for the export of copper and other minerals from the Sinai Peninsula. The harbor, which was built on the Red Sea shore in the Wadi al-Jarf area, 112 miles south of Suez, was discovered by a team from the French Institute for Archaeological Studies. It is thought to be 1,000 years older than any other port structure in the world. The papyrus shown above includes details of the arrangements for getting bread and beer to the workers heading out from the port (sounds like a single guy’s shopping list). Egypt’s antiquities minister, Mohamed Ibrahim, said they are the oldest papyri ever found in Egypt.

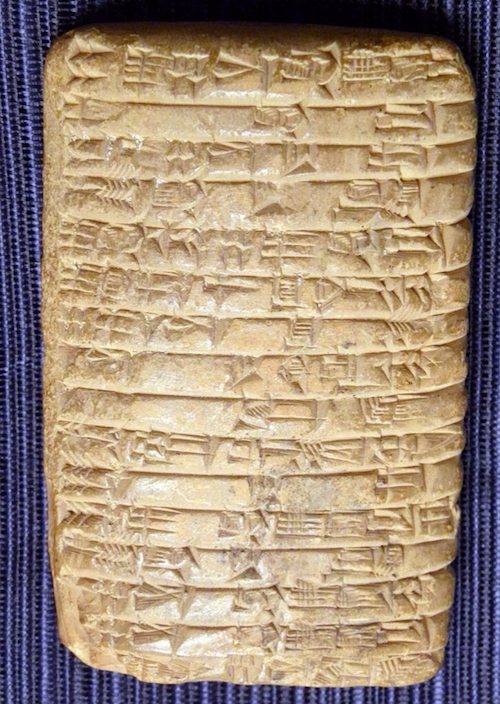

The clay tablet shown above is a Sumerian clay tablet with cuneiform text recording a list of various quantities of beer, grains, cereals, and dates collected during the harvest in the city of Umma, Mesopotamia during the 4th and 5th years of King Shu-Sin, 3rd Dynasty of Ur (2036-2028 BC). While this example is more of a receipt than a shopping list, it illustrates how important recording things was in the ancient world. In fact, the use of numbers, mathematics and letters came into being in Mesopotamia precisely for the purpose of creating lists. It was only later that written language evolved to tell stories and as teaching aids. Denise Schmandt-Besserat points out that writing is one of the great achievements of humankind, for at least three reasons. First, it represents a revolution in communication across space and time. That is, the ability to write allows our words to move far beyond the normal range of the voice and thus extends the expression of our thoughts geographically and through time. On this ability rests every sort of human inquiry, including history. Second, writing enables record-keeping, allowing us to study a prophet’s words, engrave a tombstone, or collect taxes. Third, writing give us a means for scrutinizing and editing our ideas, which permits us to rewrite our thoughts. As such, it opens the way to revision and greater rigor of thought, essential in logical processes of every sort, including historical investigation. Thus, the introduction of writing marks an important crux in the history of any civilization, not only because it marks a shift in mentality toward extending communication, keeping records and re-assessing thought but also because it allows a people to live on beyond their own lives and speak to a distant future. On the written word depends every form of learning ever invented, particularly history.

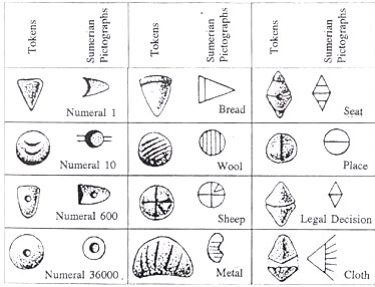

The first western scholar known to have proposed a theory in which writing has a human origin was the French scholar Diderot, editor of the first encyclopedia, in 1755. Based on an earlier suggestion by William Warburton, the bishop of Gloucester, Diderot suggested that early phonetic symbols developed out of pictographs, pictures representing ideas. A highly successful thesis, this proposition remained the basis for most explanations of the origin of writing in the West, until Denise Schmandt-Besserat introduced her theory of tokens. Much of this debate has revolved around the earliest known script in Western Civilization, cuneiform, the “wedge-shaped” system of signs used by the ancient Sumerians. But there were two major problems with postulating a pictographic origin for the great array and breadth of cuneiform signs. First, archaeological investigation has failed to produce any evidence of a forerunner for cuneiform which arose suddenly about 3000 BC. Second, there were relatively few cuneiform signs which showed a clear lineage from pictures.

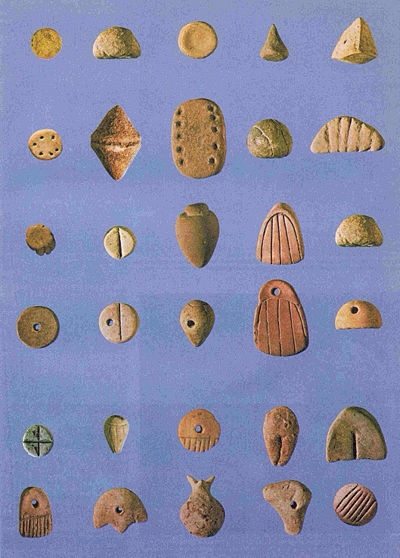

Studying Mesopotamian culture in the early 1970’s, Schmandt-Besserat first set out to investigate the uses of clay before the development of pottery in early Near Eastern culture. But as she was searching for bits of clay floors, hearth linings, beads and figurines, she kept running into massive piles of small ceramic pieces found in various shapes and sizes. There are several other things notable about the nature and disposition of these tokens. For one, they come from all over the Near East: Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Israel. For another, they date to very early times, as far back as 8000 BCE and end abruptly around 3000 BC when cuneiform was introduced. Furthermore, there is evidence some care went into their creation because many have been fired. Firing signifies a desire to preserve them, which in turn argues that they had value of some sort. They are, in fact, among the earliest fired ceramics known. The decipherment of that system became the hallmark and triumph of her career. She noted initially that several of the designs used on and for tokens resembled later cuneiform signs. From there it was not much of a conceptual leap, though its implications to history were immense, that the tokens had originally functioned as counters representing one unit of a particular item, in much the same way later cuneiform signs denoted items in written form.

Similar counting systems can be found even today all over the planet. Of particular interest here, modern shepherds in Iraq still use pebbles in counting sheep. But pebbles are undifferentiated, making it unclear what they represent. This makes it easy to understand how tokens would have been deployed in counting, as Schmandt-Besserat argues. Say, for instance, you’re a tribal chieftain and want to hold a feast. You send a runner, a young boy perhaps, off with a handful of tokens that function as a sort of “shopping list.” You could also keep for yourself an identical set as a reminder of what you’d put on your “list.” And you could even change your mind later and send off another boy with more tokens, in other words, a revised list. Later tokens even had perforations that could be used to string them together and avoid getting them lost. So if you were making a shopping list in 8000 BC, you would have a handful of clay tokens to remind you what to pick up. I will have more on the remarkable work of Denise Schmandt-Besserat and her work on the origins of writing but for now I will leave you with some fun contemporary shopping lists.

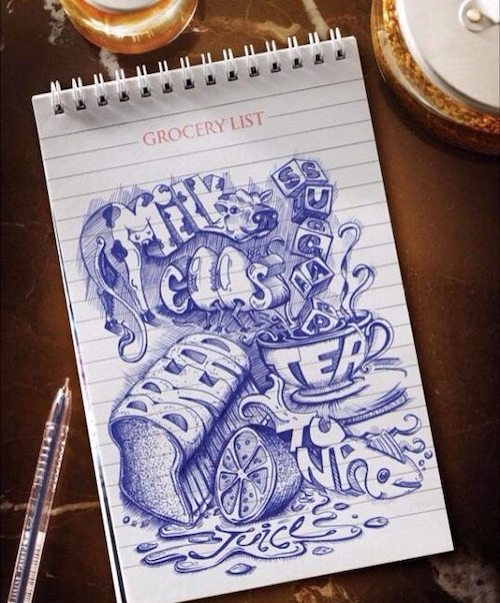

So next time you are busy scribbling out a list of what you need from the store, take a little time to doodle and think about the ten thousand year history of that little list.

References:

Openculture: http://www.openculture.com/2013/12/michelangelos-illustrated-grocery-list.html

Galileo Shopping List: http://maryloudriedger2.wordpress.com/2012/05/16/galileos-grocery-list/

Museo Galileo: http://www.museogalileo.it/

History Kitchen: http://thehistorykitchen.com/2013/07/09/leonardo-da-vincis-kitchen/

Famous People Shopping: http://lifestyle.ezinemark.com/hollywood-stars-and-celebrities-grocery-store-styles-7736ed7ed9db.html

Sebastion Lester: http://supernrmal.com/2011/09/11/this-is-a-short-but-sweet-shopping-list/

Richard Solomon: http://www.richardsolomonblog.com/2011/05/wayshaks-shopping-list.html

Egyptian Shopping List: http://www.whereintheworldisbasha.com/13-reasons-to-visit-londons-british-museum-3641/

Ephemeral Lists: http://www.english.illinois.edu/-people-/faculty/schaffner/shoppinglists/

Worlds oldest port: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2309930/Worlds-oldest-port-believed-Egypt-alongside-papyri-revealing-fascinating-details-life-Ancient-Egyptians.html

Origins of Writing: http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/1320Hist%26Civ/chapters/16TOKENS.htm

Grocery list: http://www.grocerylists.org