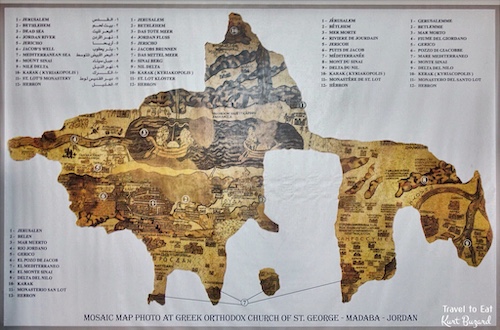

The Madaba Map (also known as the Madaba Mosaic Map) is part of a floor mosaic in the early Byzantine church of Saint George at Madaba, Jordan. The Madaba Map is a map of the Middle East and associated holy places. It contains the oldest surviving original cartographic depiction of the Holy Land and especially Jerusalem. While modern maps are labeled as if you stand on the south pole and look north. The Madaba map is labeled from the north looking south. This means that the lettering of the map is upside down to how we would orient the map on paper. It is like looking at a map of the United States 180 degrees (upside down). The Madaba map is not to scale. Jerusalem is greatly enlarged and distances are greatly distorted to what we would expect from a map. But the map was for devotional purposes, not science and geography as we would like it to have been from a modern perspective. Nonetheless the map is extraordinarily precise, including many cities known from other sources.

The Madaba Mosaic Map depicts Jerusalem with the Nea Church, which was dedicated on November 20, 542 CE. Buildings erected in Jerusalem after 570 are absent from the depiction, thus limiting the date range of its creation to the period between 542 and 570. The mosaic was made by unknown artists, probably for the Christian community of Madaba, which was the seat of a bishop at that time. In 614, Madaba was conquered by the Persian empire. In the 8th century AD, the Muslim Umayyad rulers had some figural motifs removed from the mosaic. In 746, Madaba was largely destroyed by an earthquake and subsequently abandoned. The mosaic was rediscovered in 1884, during the construction of a new Greek Orthodox church on the site of its ancient predecessor.

As I have said, the mosaic was rediscovered in 1884, during the construction of a new Greek Orthodox church on the site of its ancient predecessor. In the following decades, large portions of the mosaic map were damaged by fires, activities in the new church and by the effects of moisture. In December 1964, the Volkswagen Foundation gave the Deutscher Verein für die Erforschung Palästinas (“German Society for the exploration of Palestine”) 90,000 DM to save the mosaic. In 1965, the archaeologists Heinz Cüppers and Herbert Donner undertook the restoration and conservation of the remaining parts of the mosaic. In any other place than the Middle East, this mosaic would be in a museum. Instead, this remains a working church, the mosaic is covered with a rug during services.

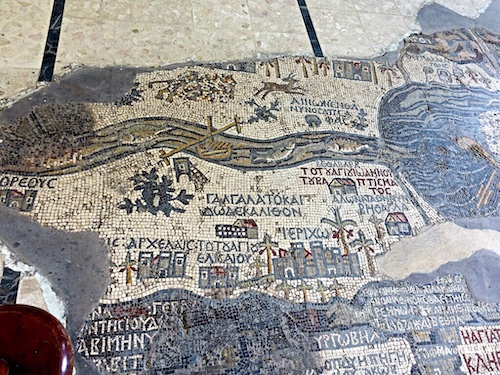

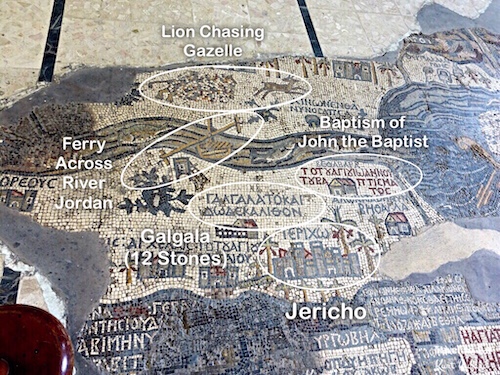

Most of the labels are in Cisjordan (modern Israel), and are concerned with Biblical locales, regional names, and events. For example, the map marks Jericho with palm trees, 12 stones at Gilgal, Jacob’s well in Shechem, tribal allotments, the Oak of Mamre at Hebron, John’s baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River, Benjamin, Judah, and Bethlehem.

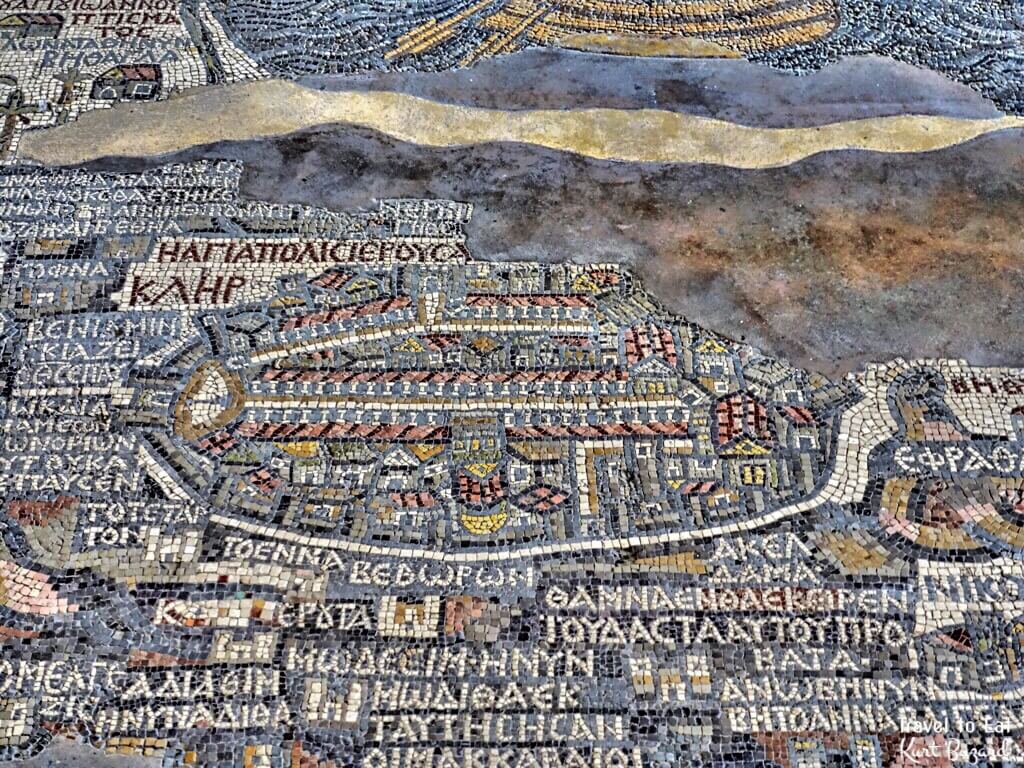

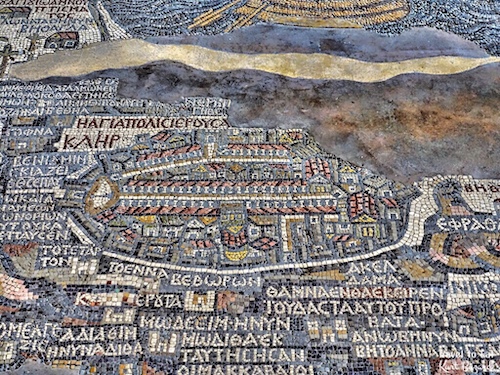

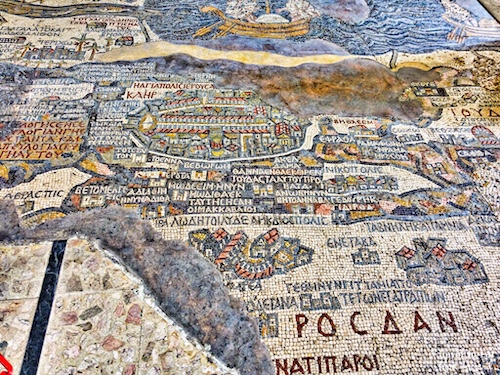

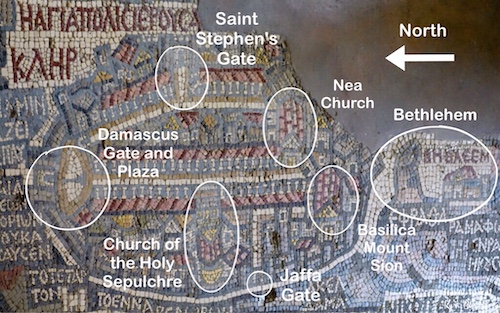

The amount of detail in the depiction of Jerusalem is amazing and allowed historians to accurately date the time of the maps creation. The city is shown as viewed from the air, surrounded by walls. The main streets are porticoed and start from a plaza, just inside the northern gate, where a column is standing alone. The cardo, an integral component of city planning, was lined with shops and vendors, and served as a hub of economic life. The main cardo was called cardo maximus. The central street of the Cardo is 40 feet (12 m) wide and is lined on both sides with columns. The total width of the street and shopping areas on either side is 70 feet (22 m), the equivalent of a 4-lane highway today. This street was the main thoroughfare of Byzantine Jerusalem and served both residents and pilgrims. Large churches flanked the Cardo in several places. In 1967, excavations in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem revealed the Nea Church and the Cardo Maximus in the very locations suggested by the Madaba Map. Religious and public buildings are represented with red gabled roofs. The Basilica built by Emperor Constantine on the place of the death and resurrection of Christ (Church of the Holy Sepulchre) presents a big yellow (gilded) cupola to the west and stairs to the east. Before the name of Jerusalem the inscriptions put its new attribute of “Holy City”.

Though an old song says the River Jordan is “deep and wide”, the modern river it is neither. In places it is more like a creek than a river, less than 10 meters across and 2 meters deep. From Jesus’ time until the mid 20th century, seasonal flooding in winter and spring expanded its width to 1.5km. Dams in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon and Israel now preclude flooding. This portion of the map shows the Jordan river flowing into the Dead Sea with fish in the river and a pulley driven ferry. Most of the labels are in Cisjordan (modern Israel), and are concerned with Biblical locales, regional names, and events. For example, the map marks Jericho with palm trees, 12 stones at Gilgal, Jacob’s well in Shechem, tribal allotments, the Oak of Mamre at Hebron, John’s baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River, Benjamin, Judah, and Bethlehem.

In an isolated fragment of the mosaic there is the port of Askalon (Ashkelon) on the coast of Israel just above the Gaza Strip. Ashkelon was the oldest and largest seaport in Canaan, one of the “five cities” of the Philistines, north of Gaza and south of Jaffa (Yafa). The vignette of the city shows a network of colonnaded and porticoed roads. Outside the city walls there is the shrine of the Egyptian Martyrs, Ares, Promos and Elijah, which was venerated by the pilgrims. The only surviving part of the vignette depicting the city of Gaza, comparable in size to that of Jerusalem, shows the south of the city. Two porticoed streets run across the city intersecting one another in a central square. The south east sector shows a horseshoe shaped theater, while the south western area is occupied by a grand ecclesiastical complex. Philistia was, according to Joshua 13:3 and 1 Samuel 6:17, a Pentapolis (group of five cities) in south-western Levant, comprising Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza. Philistia ruled major parts of southern Canaan at the peak of its expansion, but was eventually conquered and subdued by the neighboring Israelites.

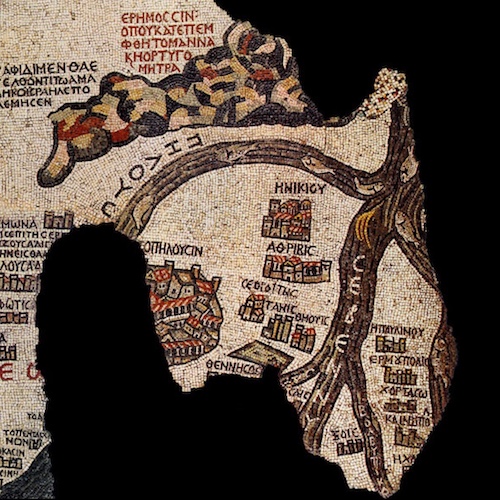

The final part of the map shows the Sinai desert and the Nile Delta. This part of the map follows the route of the exodus of the Jews from Egypt. It is also remarkably accurate with respect to the Nile, the mountains in the Sinai and the towns along the way. The Nile Delta is shown with the traditional seven branches as represented in greek geography. Only five survive, whose names, except for the Pelusiac branch, are written in the river flow; Saitic, Sebennytic, Bucolic and Bulbytic.

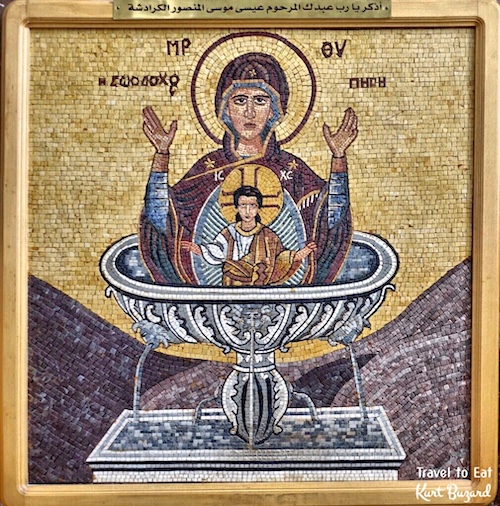

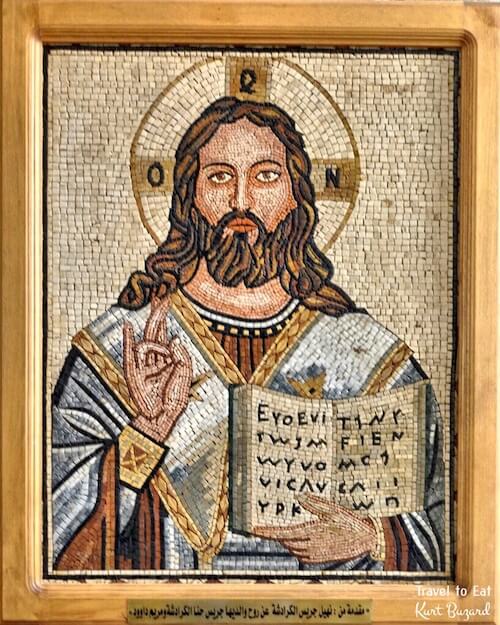

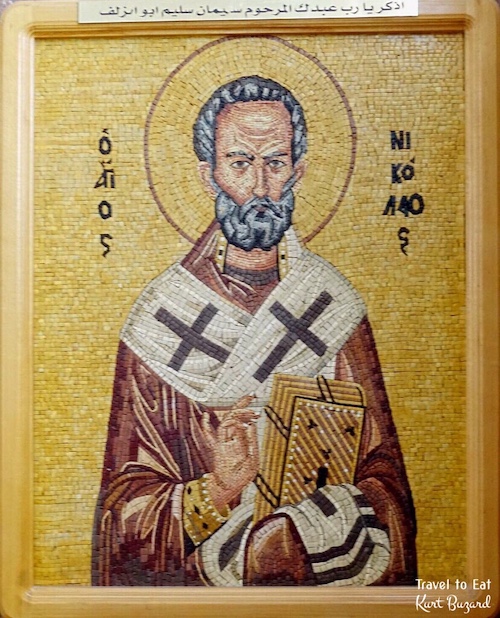

Not surprisingly, mosaics are very popular in Madaba and the church is decorated with very fine examples. The traditional legends have offered a historicised narration of George’s encounter with a dragon. Eastern Orthodox depictions of Saint George slaying a dragon often include the image of a young woman who looks on from a distance. The standard iconographic interpretation of the image icon is that the dragon represents both Satan (Rev. 12:9) and the monster from his life story. The young woman is the wife of Diocletian, Empress Alexandra. Thus, the image, as interpreted through the language of Byzantine iconography, is an image of the martyrdom of the saint. The episode of George and the dragon was a legend brought back with the Crusaders and retold with the courtly appurtenances belonging to the genre of chivalric romance. Madaba is full of history and mosaics in addition to the Madaba mosaic map. If you get a chance you should visit. I hope you enjoyed, please leave a comment.[mappress mapid=”181″]

References:

Madaba Map Site: http://www.christusrex.org/www1/ofm/mad/

Madaba Map: http://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-exodus-madaba-map.htm

Madaba Map: http://www.bible.ca/archeology/bible-archeology-exodus-madaba-map.htm