Last year I had the privilege of visiting Madagascar to see the unique animals and plants often found only there. The prehistoric breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana separated the Madagascar–Antarctica–India landmass from the Africa–South America landmass around 135 million years ago (mya). Madagascar later split from India about 88 mya, allowing plants and animals on the island to evolve in relative isolation. Fossils from Africa and some tests of nuclear DNA suggest that lemurs made their way to Madagascar between 40 and 52 mya. Other mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence comparisons offer an alternative date range of 62 to 65 mya. An ancestral lemur population is thought to have inadvertently rafted to the island on a floating mat of vegetation, although hypotheses for land bridges and island hopping have also been proposed. Any extended ocean voyage without fresh water or food would prove difficult for a large, warm-blooded mammal, but today many small, nocturnal species of lemur hibernate, which allows them to lower their metabolism and become dormant while living off fat reserves facilitating the ocean voyage. Having undergone their own independent evolution on Madagascar, lemurs have diversified to fill many niches normally filled by other types of mammals. They include the smallest primates in the world, and once included some of the largest. Lemurs belong to a group called prosimian primates, defined as all primates that are neither monkeys nor apes. Though there are many species of lemur, there are very few individuals. Lemurs are considered the most endangered group of animals on the planet.

Brown Mouse Lemur

The mouse lemurs are nocturnal lemurs of the genus Microcebus. Like all lemurs, mouse lemurs are native to Madagascar. There are more than 24 species of mouse lemurs, and several have been identified only in recent years. This is a rarity in primate research, and illustrates just how much remains to be known about these fascinating animals. Mouse lemurs have a combined head, body and tail length of less than 11 in (27 cm), making them the smallest primates and include the world’s smallest primate, Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur, which is only 3.9 in (10cm) long. Mouse lemurs are considered cryptic species, with very few morphological differences between the various species, but with high genetic diversity. Recent evidence points to differences in their mating calls, which is very diverse. Since mouse lemurs are nocturnal, they might not have evolved to look differently, but had evolved various auditory and vocal systems to differentiate themselves. The mouse lemurs are among the shortest-lived of primates. The brown mouse lemur has a lifespan of 6–8 years in the wild, although it averages 12 years under human care. Mouse lemurs are omnivorous; their diets are diverse and include insect secretions, arthropods, small vertebrates, gum, fruit, flowers, nectar, and also leaves and buds depending on the season. I saw this one on a night walk in Andasibe-Mantadia National Park (Reserve of Perinet) near the Vakona Forest Lodge.

Crossley’s Dwarf Lemur

The furry-eared dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus crossleyi), or Crossley’s Dwarf Lemur has a coloration that is red-brown on the back and gray on the underside. The eye-rings of this species are blackish and the ears are black inside and out. Measuring an average of 9.4–10.3 in (24–26.2 cm) in body length with a tail about 9.4–10.9 in (24–27.7 cm) and a weight of 13–13.5 oz (368–383 gm), they are larger than the mouse lemur but smaller than the bamboo lemur. Their heads are spherical compared to the fox-like heads of the lemurs, but their muzzles are more pointed. The dwarf lemurs of Madagascar (Cheirogaleus) are the only primates that hibernate. The heart rate of an active dwarf lemur is around 180 beats per minute, but during hibernation it can drop to as low as four beats per minute. Body temperature, which usually hovers around 97 degrees F (36 degrees C), can plunge to almost freezing at a frigid 41 degrees F (5 degrees C). They hibernate during the dry, cold months of April-September for 4–5 months. Crossley’s Dwarf Lemurs choose to hibernate buried under a spongy layer of root, humus and leaf matter in small underground burrows, no more than 15 inches deep. Each lemur keeps its own burrow, but family members often hibernate in close proximity to one another. The burrowing behavior is particularly odd considering that these squirrel-sized primates live up in the trees throughout the rest of the year.

Eastern Lesser Bamboo Lemur

The Eastern Lesser Bamboo Lemur (Hapalemur griseus), also known as the Gray Bamboo Lemur, the gray gentle lemur, and the Mahajanga lemur is a small, very cute lemur endemic to Madagascar, with three known subspecies. One of the smallest of the bamboo lemurs, it has a dense, woolly coat that is grey to olive-grey on the upperparts, with chestnut-brown tinges on the head, shoulders, and sometimes the back. The face and underparts are a paler grey, becoming creamy-grey/tan on the belly, and the long tail is generally dark. Like other bamboo lemurs, the head is rounded, and bears a characteristically short muzzle and small, furry ears. It averages 11 in (284 mm) in length with a tail of 1.5 in (37 mm). As its name suggests, bamboo lemurs specialise in feeding almost exclusively on bamboo, and are the only primates known to do so. Bamboo constitutes at least 75 percent of the diet of the eastern lesser bamboo lemur, with the rest made up of fig leaves, grass stems, other young leaves, small fruits, flowers and fungi. Each species of bamboo lemur appears to specialise on different parts of the bamboo plant, with the eastern lesser bamboo lemur preferring the new shoots, leaf bases and stem pith. Bamboo contains very little nutritional value so, like the panda, the bamboo lemur must eat a large amount each day. Fortunately, bamboo grows more readily when the primary forest is cut down, thus the bamboo lemur is one of the few animals to benefit from human activity. The eastern lesser bamboo lemur is the most widespread of the bamboo lemurs, it is found throughout many of the forests of eastern Madagascar

Common Brown Lemur

The Common Brown Lemur (Eulemur fulvus) lives in western Madagascar north of the Betsiboka River and eastern Madagascar between the Mangoro River and Tsaratanana, as well as in inland Madagascar connecting the eastern and western ranges. The common brown lemur has a total length of 33 to 40 in (84 to 101 cm), including 16 to 20 in (41 to 51 cm) of tail. Weight ranges from 4.4 to 6.6 lb (2 to 3 kg). The short, dense fur is primarily brown or grey-brown. The face, muzzle and crown are dark grey or black with paler eyebrow patches, and the eyes are orange-red. The common brown lemur’s diet consists primarily of fruits, young leaves, flowers and insects. It also eats bark, sap, soil and red clay. It can tolerate greater levels of toxic compounds from plants than other lemurs can. The common brown lemur lives in a wide variety of forest types, from lowlands to mountains, from evergreen forests to deciduous forests. This range likely factors into its status as near threatened, rather than endangered or critically endangered like so many of its cousins. The common brown lemur is mostly active during the day but like the mongoose lemur, it can be active throughout the night and day as well. In fact, these two species sometimes share territory, and adjusting the times of their activity helps them avoid conflict and peaceably divvy up the resources of their forest homes.

Red-Fronted Brown Lemur

The Red-Fronted Lemur (Eulemur rufifrons), also known as the red-fronted brown lemur or southern red-fronted brown lemur, is a species of lemur from Madagascar. Until 2001, it was considered a subspecies of the common brown lemur. Red-fronted lemurs are about the size of a house cat and weigh between 4.5 and 8 pounds (2 to 4 kilograms). Their tails can measure as long as 22 inches (56 centimeters). It has a gray coat and black face, muzzle and forehead, plus a black line from the muzzle to the forehead, with white eyebrow patches. Males have white or cream colored cheeks and beards, while females have rufous or cream cheeks and beards that are less bushy than males. Red-fronted lemurs live in deciduous forests in western and eastern Madagascar. It lives in dry lowland forests. They are mainly folivorous, or leaf-eating, lemurs. They can also eat flowers, fruit and bark. However, red-fronted lemurs have very adaptable diets, shifting to invertebrates and fungi when plant matter is scarce. Western populations are primarily diurnal, but increase nocturnal activity during the dry season, while eastern populations show less such dichotomy.

Black and White Ruffed Lemur

The Black-and-White Ruffed Lemur (Varecia variegata) is an Endangered Species of ruffed lemur population, one of two which are endemic to the island of Madagascar. This visually striking species hails from the tropical forests of eastern Madagascar, where its thick fur is well suited to the wet, sometimes chilly environment of the rainforest canopy. Weighing between 6.8 and 9.0 lb (3.1 and 4.1 kg) and ranging in length from 3.3 to 3.9 ft (100 to 120 cm), black and white ruffed lemurs are among the largest living lemurs. Ruffed lemurs’ diets consist primarily of fruit, nectar, and pollen. As fruit-eaters, they play an important role as seed dispersers in Madagascar’s rainforests: They can swallow large seeds, which pass through their guts undigested and are excreted onto the forest floor in their own packets of “fertilizer” (feces). If large seed-dispersers like ruffed lemurs disappear, these large trees could disappear too. Ruffed lemurs are the largest pollinators in the world. When feeding on the nectar of the traveler’s palm (Ravenala madagascariensis), black and white ruffed lemurs pry open the blooms and push their long, narrow muzzles deep into the nectar chamber. As they do so, pollen sticks to the ruffed fur around the lemurs’ faces and gets transported from tree to tree. The black and white ruffed lemur is critically endangered in Madagascar, primarily due to hunting and habitat loss and fragmentation. Threats include slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy) and illegal logging and mining, as well as natural disasters like cyclones.

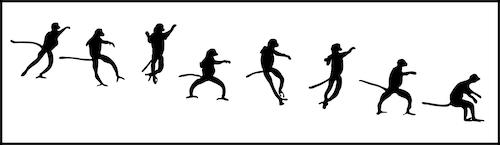

Verreaux’s Sifaka Lemur

Verreaux’s Sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi), or the white sifaka, is a medium-sized primate in one of the lemur families, the Indriidae. The name of the sifaka comes from the sharp, piercing call that this primate makes, which sounds like shi-fahk. It lives in southern Madagascar and can be found in a variety of habitats from rainforest to western Madagascar dry deciduous forests and dry and spiny forests. Its fur is thick and silky and generally white with brown on the sides, top of the head, and on the arms. Like all sifakas, it has a long tail that it uses as a balance when leaping from tree to tree. However, its body is so highly adapted to an arboreal existence, on the ground its only means of locomotion is hopping. On the ground it bounds along on its hind legs, with its arms held out and above the head for balance, in the manner of a graceful dancer. In adulthood, the full head and body length is between 17–18 in (42–45 cm). The tail of a fully grown Verreaux’s sifaka grows to be between 22–24 in (56–60 cm) long. In weight, adult females reach 7.5 lb (3.4 kg) on average, and adult males 7.9 lb (3.6 kg). Importantly for a species living in a frequently dry habitat, Verreaux’s sifaka seems able to tolerate conditions of drought; it gains moisture from eating the succulent leaves of certain plants (Didiereaceae species) and will also lick dew from its coat to gain extra water. The species lives in small troops which forage for food. They are herbivores; leaves, fruit, bark and flowers are typical components of the diet. However, they are mostly folivorous (leaves represent the majority of the diet over the year, especially in the dry season) and they seem to choose food items based on quality (lower tannin content) rather than on availability.

Coquerel’s Sifaka Lemur

The Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli) is a diurnal, medium-sized lemur of the sifaka genus Propithecus. It is native to Madagascar. The Coquerel’s sifaka was once considered to be a subspecies of the Verreaux’s sifaka, but was eventually granted full species level. Like Verreaux’s Sifaka the Malagasy name “sifaka” comes from the distinct call this animal makes as it travels through the trees, “shi-fahk.” Coquerel’s sifaka is a vertical clinger and leaper with long, powerful hind legs and an upright posture. It has a head-body length of 16.5–19.7 in (42–50 cm) and a tail length of 20–24 in (50–60 cm). The total mature length (including tail) is approximately 36.6–43.3 in (93 to 110 cm). Adult body mass is typically around 8.8 lb (4 kg). Coquerel’s sifaka (Propithecus coquereli) are delicate leaf-eaters from the dry northwestern forests of Madagascar. The sifaka of Madagascar are distinguished from other lemurs by their mode of locomotion: these animals maintain a distinctly vertical posture and leap through the trees using just the strength of their back legs. Their spectacular method of locomotion is known as vertical clinging and leaping and their long, powerful legs can easily propel them distances of over 20 feet from tree to tree. On the ground, the animals cross treeless areas just as gracefully, by an elegant bipedal sideways hopping. Coquerel’s sifaka are classified as endangered in Madagascar and are threatened with increasing habitat destruction and the erosion of social customs against hunting this species.

Diademed Sifaka Lemur

The Diademed Sifaka (Propithecus diadema), or diademed simpona, is a criticality endangered species of sifaka, one of the lemurs endemic to Mantadia National Park and other rainforests in eastern Madagascar. It is also known by the Malagasy names simpona, simpony and ankomba joby. In addition to the “shi-fahk” call of all Sifaka, the diademed sifaka makes a warning call resembling the sound “kiss-sneeze” when a terrestrial predator is perceived. This species is the second largest living lemur, after the Indri Lemur. The head and body length is 19.7–21.7 in (50–55 cm) with a tail length of 17.3–19.7 in (44–50 cm) and a weight of 10.5–18.7 lb (4.75–8.5 kg). Widely regarded as the most beautiful of all the primates of Madagascar, the diademed sifaka is indeed striking. Its bare, dark grey or black face is framed with contrasting white hair, and on top of the head is a patch of black. The resemblance of this to a “diadem”, the ornamental headband or crown worn by royalty, is the source of this species English name. Its long, silky fur is typically grey on the back, and rich orange or golden on the arms and legs. The hands and feet are black, and there is often a golden-yellow area around the base of the grey or white tail. The Diademed Sifaka is thought to traverse the greatest daily distance relative to other members of its family in its patrolling and foraging, traveling in excess of one mile (1.6 km) per day. To accomplish this it consumes a diet high in energy content and diverse in plant content, each day consuming over 25 different vegetative species. This diurnal lemur further diversifies its diet by consuming not only fruits, but certain flowers, seeds and verdant leaves, in proportions that vary by season.

Milne-Edwards’ Sifaka

Milne-Edwards’ Sifaka (Propithecus edwardsi), or Milne-Edwards’ simpona, is an endangered large arboreal, diurnal lemur endemic to the eastern coastal rainforest of Madagascar such as Ranomafana National Park where I found these. Milne-Edwards’ Sifaka is characterized by a black body with a light-colored “saddle” on the lower part of its back. It is closely related to the diademed sifaka, and was until recently considered a subspecies of it. Like all sifakas, it is a primate in the Indri family Indriidae. The average weight of a male Milne-Edwards’ sifaka is 13.0 lb g (5.90 k) and for females it is 13.9 lb (6.30 kg). The body length excluding the tail is 18.7 in (47.6 cm) for males and females measure 18.8 in (47.7 cm). The tail is slightly shorter than the body, averaging 17.9 in (45.5 cm) in length or about 94% of the total head and body length. The Milne-Edwards’ sifaka has orange-red eyes and a short, black, bare face ringed by a puffy spray of dark brown to black fur. The majority of its coat is dark brown or black long silky fur, but on the center of the sifaka’s back and flanks is a brown to cream colored saddle shaped area which is divided in half by a line of dark fur along the spine. The shape and coloration of the saddle patch vary by individual and are not always present, sometimes they are replaced by silver-tipped hairs as seen above. The Milne-Edwards’ sifaka’s diet is composed primarily of both mature and immature leaves and seeds, but they also regularly consume flowers and fruit. They also supplement their diet with soil and subterranean fungus. In the process of foraging, the Milne-Edwards’ sifakas range an average of 670 m (2,200 ft) per day.

Indri Lemur

The namesake of the Indriidae family is the Indri (Indri indri), also called the babakoto, of the montane forests of eastern Madagascar. The name “indri” most likely comes from a native Malagasy name for the animal, endrina. An oft-repeated, but probably incorrect story is that the name comes from indry meaning “there” or “there it is”. French naturalist Pierre Sonnerat, who first described the animal, supposedly heard a Malagasy point out the animal and took the word to be its name. It is the largest living lemur, with a head-and-body length of about 25–28 in (64–72 cm) and a weight of between 13 to 21 lb (6 to 9.5 kg). It has a black and white coat and maintains an upright posture when climbing or clinging. Its large greenish eyes and black face are framed by round, fuzzy ears that some say give it the appearance of a teddy bear. Unlike any other living lemur, the Indri has only a rudimentary tail. The silky fur is mostly black with white patches along the limbs, neck, crown, and lower back. Analamazaotra, better known as Perinet, is world famous for its population of Indri lemurs. The Indri feeds on canopy fruits and leaves and is best known for its eerie yet beautiful song, which can carry for more than 1.2 miles (2 km). This diurnal lemur will bark when confronted with danger, and make kissing sounds when affectionate. Despite its large size, the Indri refuses to move along the ground, and will negotiate gaps by leaping, often over 33 feet (10 m) between tree trunks. Illegal hunting is a major problem for the Indri in certain areas. Although long thought to be protected by local fadys (traditional taboos), these do not appear to be universal and the animals are now hunted even in places where such tribal taboos do exist. In many areas these taboos are breaking down with cultural erosion and immigration, and local people often find ways to circumvent taboos even if they are still in place. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated its conservation status as “critically endangered”.

Ring-Tailed Lemur

The Ring-Tailed Lemur (Lemur catta) is the most recognized lemur due to its long, black and white ringed tail. Known locally in Malagasy as “maky”, it inhabits gallery forests to spiny scrub in the southern regions of the island. It is omnivorous and the most terrestrial of extant lemurs. The animal is diurnal, being active exclusively in daylight hours. The Ring-Tailed Lemur has a head and body length of 15–17.75 in (38–45 cm), with a tail length of 22–24.5 in (56–62 cm) and a weight of 4.4–5.3 lbs (2–2.4 kg). The ring-tailed lemur’s dense fur is grey to rosy brown on the back and grey on the rump and limbs. The underparts are cream to off-white, and the neck and crown are dark grey. The ring-tailed lemur has a white face with large, dark triangular patches around the eyes, a dark snout, and large, white, well-furred ears. Dark black skin is visible on the ring-tailed lemur’s nose, eyelids, lips and feet. This species’ distinctive tail is longer than the head and body, and is white striped with black. The only species in its genus, the ring-tailed lemur receives its genus name, Lemur, from the Latin for ‘ghost’ or ‘spirit’, and its species name catta in reference to its cat-like form. The ring-tailed lemur is an opportunistic omnivore primarily eating fruits and leaves, particularly those of the tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica), known natively as kily, which makes up as much as 50% of the diet, especially during the dry, winter season. The ring-tailed lemur also eats flowers, herbs, bark and sap. It has been observed eating decayed wood, earth, insects and small vertebrates (birds and chameleons). Despite reproducing readily in captivity and being the most populous lemur in zoos worldwide, the ring-tailed lemur is listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List due to habitat destruction and hunting for bush meat and the exotic pet trade. As of early 2017, the population in the wild is believed to have crashed as low as 2,000 individuals.

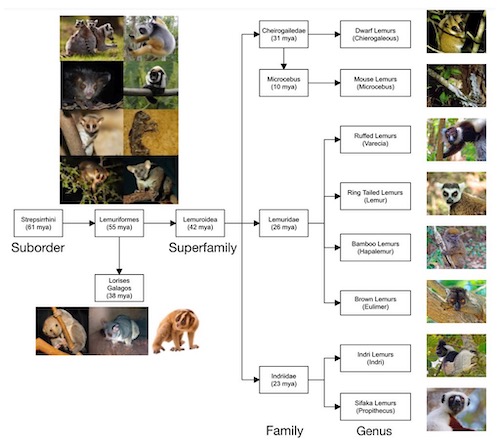

Lemur Evolutionary History

If you were wondering how all these animals fit together in the evolutionary tree, I have provided a phylogenetic tree which shows approximately when divergences occurred between the various groups and which lemurs are grouped together. Because these are primates or prosimians, there is a fair amount of discussion concerning the classifications and research is ongoing. The chart looks a little intimidating but I will go into more detail and explain it in a future post. I plan to write several more posts specifically on hereditary, reproduction, baby lemurs and other interesting lemur subjects. I hope you enjoyed seeing these pictures of these endangered and beautiful lemurs as much as I did taking them, please leave a comment.

References:

Crossley’s Dwarf Lumur, IUCN Red List

More Hibernation in Dwarf Lemurs

Crossley’s Dwarf Lemur Hibernation Study

Black and White Ruffed Lemur, Red List