For the last year I have been walking around Las Vegas every day with my camera for exercise and to avoid going mental. Over that time period I have accumulated a collection of lizard photos which I thought would make a nice post. Even though there are lots of little lizards in the Mohave desert (more than 20 species), even in the urban landscape of Las Vegas, most photos are fortuitous since they are so quick and usually small. Lizards and iguanas both belong to the reptile group of vertebrates. The Squamata, or the scaled reptiles, are the largest recent order of reptiles, comprising all lizards and snakes. Iguanas are actually a type of lizard. Therefore, they are not very different from lizards in many aspects. However, they are different from most lizard species in several ways including their colors and the foods they eat. Many lizard species are insectivorous. They like eating insects such as cockroaches, crickets, ants, and beetles. Many lizard species are also omnivorous; they eat just about everything including insects, carrion, small tetrapods, spiders, fruits, and vegetables. Iguanas tend to be herbivores. Of the many species of swifts and spiny lizards, 22 species, some with several subspecies, occur in the United States. Others are found southward through Mexico to northern Panama. In the United States, the lizards of this group are found from southern New York, southern South Dakota and northern Washington in the north, to South Florida, the Gulf States and the Mexican border. Several of the fence lizards (which, because of their rapid movements, are colloquially referred to as “swifts”) are familiar backyard species. Others, among them the bunchgrass lizards and Yarrow’s spiny lizard, are denizens of remote montane fastnesses. Like many other lizards, spiny lizards exhibit metachromatism, which is color change as a function of temperature. When it is cooler, colors are much darker than when the temperature is high. Darker colors increase the amount of heat absorbed from the sun and lighter colors reflect solar radiation.

Common Side-Blotched Lizard

The common side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) is native to dry regions of the western United States and northern Mexico. This is the most common small lizard around Las Vegas. Males can grow up to 60 mm (2.4 inches) from snout to vent, while females are typically a little smaller. The degree of pigmentation varies with sex and population. Some males can have blue flecks spread over their backs and tails, and their sides may be yellow or orange, while others may be unpatterned. Females may have stripes along their backs/sides, or again may be relatively drab. Both sexes have a prominent blotch on their sides, just behind their front limbs. Coloration is especially important in common side-blotched lizards, as it is closely related to the mating behavior of both males and females. It is notable for having a unique form of polymorphism wherein each of the three different male morphs utilizes a different strategy in acquiring mates.

The three morphs compete against each other following a pattern of rock paper scissors, where one morph has advantages over another but is outcompeted by the third. Orange-throated males are “ultra-dominant, high testosterone”, that establish large territories and control areas that contain multiple females. Yellow stripe-throated males (“sneakers”) do not defend a territory, but cluster on the fringes of orange-throated lizard territories, and mate with the females on those territories while the orange-throat is absent, as the territory to defend is large. Blue-throated males are less aggressive and guard only one female; they can fend off the yellow stripe-throated males, but cannot withstand attacks by orange-throated males. Female side-blotched lizards have also been shown to exhibit behaviorally correlated differences in throat coloration. Orange-throated females are considered r-strategists. They typically produce large clutches consisting of many small eggs. In contrast, yellow-throated females are K-strategists that lay fewer, larger eggs.

The systematics and taxonomy of the widespread and variable lizards of the genus Uta is much disputed. Countless forms and morphs have been described as subspecies or even distinct species. There are two subspecies of Common Side-blotched Lizards in California and Nevada. They are very similar in appearance, but the Nevada Side-blotched Lizard usually has a more reduced, often uniform pattern consisting of mostly scattered light and dark spotting. The Western Side-blotched Lizard (Uta stansburiana elegans) subspecies is marked with a stronger dorsal pattern of spots and wedges and is the one found around Las Vegas. A distinguishing feature of both sub-species is the dark blotch behind the front leg. The blotch is generally less prominent in females than in males. Males tend to be unpatterned, but speckled with blue during the breeding season. Females tend to have a row of dark blotches along each side of the back the converging in the middle of the back, also one row of blotches down the top of the tail. Studies show that the Common Side-blotched Lizard is short-lived, with most breeding occurring by animals one year or less of age. Survival from hatching to nine months was 19–31% in Rock Valley, Nevada, and few survived more than two years (Turner et al. 1982).

Great Basin Whiptail

The Western Whiptail (Aspidoscelis tigris) ranges throughout most of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, including Nevada. There are 16 subspecies but only one in Nevada, the Great Basin Whiptail (Aspidoscelis tigris tigris). It lives in a wide variety of habitats, including deserts and semiarid shrubland, usually in areas with sparse vegetation; it also may be found in woodland, open dry forest, and riparian growth. It lives in burrows. Major differences between this species and the checkered whiptail (Aspidoscelis tesselatus) include the lack of enlarged scales anterior to the gular fold and the presence of enlarged postantebrachial scales. The western whiptail has a long and slender body, small grainy scales on its back, and larger rectangular scales on its belly. The upper side often has 4 light stripes which fade with age, and the throat can be pinkish or somewhat orange in adults. The tail can reach up to two times the length of the body. The western whiptail mostly eats insects, spiders, scorpions, lepidopterans (butterflies and moths), crickets, grasshoppers, and beetles. They use their jaws instead of their tongue to capture their prey. Western Whiptails can get to almost 2 feet in length from the snout to the end of the tail.

Sonoran Spotted Whiptail Lizard

The Sonoran spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis sonorae) is found in Arizona and New Mexico (not Nevada) in the United States, and Mexico. The Sonoran Spotted Whiptail (Aspidoscelis sonorae) is a moderate-sized whiptail with a dorsal pattern of 6 distinct light stripes on a brown to chocolate-brown background in both adults and juveniles. The stripes may fade in the oldest individuals but always remain distinct on the neck. In the dark fields between the dorsal stripes are small, light spots that usually do not overlap the stripes; although hatchlings and young juveniles lack spots. Rarely, adults may show blue coloration on the head, neck, limbs, tail, and sides of the body. This is an active, diurnal lizard, often seen poking and scratching in leaf litter for insects. It is mostly active from April into September.

Chihuahuan Spotted Whiptail Lizard

The Chihuahuan Spotted Whiptail (Aspidoscelis exsanguis) is native to the United States in southern Arizona, southern New Mexico and southwestern Texas, and northern Mexico in northern Chihuahua and northern Sonora (not Nevada). It is a moderately-sized, striped and spotted whiptail. There are 6 (rarely a 7th median) light dorsal stripes that fade with age, but are always visible on the neck. In the dark fields between the light stripes are many small, light spots that also overlay the light stripes. Light spots atop the hind limbs and towards the rear of the dorsum are generally brighter than the anterior spots. Hatchlings and juveniles have more distinct light dorsal stripes and fewer and less discernable light spots, or the light spots may be absent. The venter (combined rectum and bladder) of adults and juveniles is milky white. The latter half of the tail is greenish-gray in adults, and blue or green in juveniles. This species resembles other striped and spotted whiptails. It differs from the Sonoran Spotted Whiptail (A. sonorae) and Gila Spotted Whiptail (A. flagellicaudus) in having more, small light spots, some of which overlap the light stripes, and light spots on the dorsal surface of the hind legs. Phil Medica (1967) studied a population of the Chihuahuan Spotted Whiptail in south-central New Mexico, where the lizards inhabited a saltgrass, tumbleweed, saltcedar, and saltbush area. Diet included (by volume) Lepidoptera (mostly moths and their larvae) – 28%, beetles (19.7%), grasshoppers, crickets, and their relatives (8.13%), spiders (9.3%), antlions (2.5%), and termites (<1%).

Desert Horned Lizard

This species of lizard has a distinctive flat body with one row of fringe scales down the sides. They are a medium sized lizard and can grow up to approximately 3.75 inches or 95mm in size. They have one row of slightly enlarged scales on each side of the throat. Colors can vary and generally blend in with the color of the surrounding soil, but they usually have a beige, tan, or reddish dorsum with contrasting, wavy blotches of darker color. They have two dark blotches on the neck that are very prominent and are bordered posteriorly by a light white or grey color. They also have scattered pointed scales and other irregular dark blotches along the dorsum of their body. Unlike other horned lizards, Phrynosoma platyrhinos individuals do not have a prominent dorsal stripe. There are two subspecies which are found in a different geographic ranges: the northern desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos platyrhinos) ranging in Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, the Colorado front range, and parts of southeastern Oregon; and the southern desert horned lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos calidiarum) ranging in southern Utah and Nevada to southeast California, western Arizona, and northern Baja California. Desert horned lizards prey primarily on invertebrates, such as ants (including red harvester ants), crickets, grasshoppers, beetles, worms, flies, ladybugs, meal worms and some plant material. They can often be found in the vicinity of ant hills, where they sit and wait for ants to pass by.

Desert Spiny Lizard

In the United States it is found in the states of Arizona, California, Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah. It is also found in the Mexican states of Sonora, Baja California, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango. An adult male desert spiny lizard usually have conspicuous blue/violet patches on the belly and throat, and a green/blue color on their tails and sides. Females and juveniles have large combined dark spots on their back and belly areas, and the blue/violet and green/blue coloring is absent. Both sexes have brownish/yellow triangular spots on their shoulders. These lizards like to live near trees and will run up their tree to escape danger. It is frequently seen doing “push-ups” (a form of territorial display) on tree trunks, logs, rocks, and even roads, in areas where patches of prickly pear and other native plants remain. Schulte et al. (2006, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39(3):873–880) split the wide-ranging Desert Spiny Lizard into three species: 1) S. uniformis of the Great Basin, Central Valley of California, and the Mohave Desert, 2) S. magister of the Sonoran Desert and Colorado Plateau, and 3) S. bimaculosus of the Chihuahuan Desert. Sceloporus uniformis (Yellow-backed Spiny Lizard) occurs in extreme northwestern Arizona and along the Colorado River from about Parker to Davis Dam. Sceloporus bimaculosus (Twin-spotted Spiny Lizard) occurs in southeastern Arizona, and S. magister (Desert Spiny Lizard) occurs in much of western Arizona and portions of the Colorado Plateau and southeastern Arizona. Even though Las Vegas should be well inside the range for the Yellow-Backed Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus uniformis), these specimens from the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve look more to me like the Desert Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus magister). I could certainly be wrong.

Yellow-Backed Spiny Lizard

Sceloporus uniformis, also known as the Yellow-Backed Spiny Lizard, is native to the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. This lizard is native to the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. It is endemic to the United States, and can be found in California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. Until recently, it was considered to be a subspecies of Desert Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus magister). Sceloporus uniformis is a large robust lizard, and adults can grow to 5.5 inches in body length (snout-to-vent), with a tail slightly longer than the body. Color is brown or tan with yellow and black dorsal stripes or mottling and a black collar on the sides of the neck. Males are larger than females, and have a swollen tail base, enlarged postanal scales and femoral pores, and bluish markings on the throat and belly. Females have a pale throat and underbelly, with faint or no blue markings. The head of a female may be orange or reddish in the breeding season. Although S. uniformis is primarily an ambush predator, on occasion it will actively forage. This species will eat a variety of small invertebrates and their larvae including ants, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, centipedes, and caterpillars. Occasionally, small lizards, nestling birds, leaves, flowers and berries are also consumed.

Northern Sagebrush Lizard

The sagebrush lizard is similar to the western fence lizard, another Sceloporus species found in the western US. The sagebrush lizard can be distinguished from the western fence lizard in that the former is on average smaller and has finer scales. The keeled dorsal scales are typically gray or tan, but can be a variety of colors. The main (ground) color is broken by a lighter gray or tan stripe running down the center of the back (vertebral stripe) and two light stripes, one on either side of the lizard (dorsolateral stripes). Sceloporus graciosus will sometimes have orange markings on its sides. Three regional races of the sagebrush lizard are recognized: the southern sagebrush lizard lives in Southern California, and the western and northern races are found in many western states, including Oregon, Idaho, Colorado, Montana, Washington, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and Arizona. It eats a variety of small invertebrates, including ants, termites, grasshoppers, flies, spiders, and beetles.

Western Fence Lizard

The Western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) is a common lizard of Arizona, California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Northern Mexico, and the surrounding area. As the ventral abdomen of an adult is characteristically blue, it is also known as the blue-belly. Western fence lizards measure 5.7–8.9 cm (snout-vent length) and a total length of about 21 cm. They are brown to black in color (the brown may be sandy or greenish) and have black stripes on their backs, but their most distinguishing characteristic is their bright blue bellies. The ventral sides of the limbs are yellow. These lizards also have blue patches on their throats. This bright coloration is faint or absent in both females and juveniles. In some populations the males also display iridescent, bright turquoise blue spots on the dorsal surface. The scales of S. occidentalis are sharply keeled (ridge down the center), and between the interparietal and rear of thighs, there are 35–57 scales. The western fence lizard eats spiders and insects such as beetles, mosquitoes, and various types of grasshoppers. Fence lizards also carry a special ability to neutralize Lyme disease found in ticks. Some species of tick carry a type of spiral-shaped bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, better known as the pathogen that causes Lyme disease. In California, these fence lizards are a preferred host for ticks in their small, nymphal stage. And in 1998, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, discovered that a substance in the blood of the western fence lizard possesses an antibiotic superpower: when infected ticks latch on to a fence lizard, a pathogen-fighting protein in its blood neutralizes the Lyme. A single lizard can be infected with up to forty ticks, writes Casey. “It looks horrible, but the ticks are essentially being sanitized.”

Ornate Tree Lizard

Urosaurus ornatus, commonly known as the ornate tree lizard, is native to the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. There are ten subspecies. The ornate tree lizard may grow to a snout-to-vent length (SVL) of up to 2.3 inches (59 mm). As adults, all males have paired turquoise patches of skin on the abdomen; females lack this abdominal coloration. Male ornate tree lizards are found in a variety of colors. While not all populations contain more than one or two colors, 9 color types have been documented within U. ornatus. A population documented in Verde River, Arizona, has two types of coloration patterns among male tree lizards that account for 45% of all males. The first is characterized by a blue spot in the center of a larger orange patch on the throat fan (“dewlap”). The second has a solid orange throat fan (“dewlap”). The orange-blue males are more aggressive and defend territories that can include up to four females. The orange males have longer, leaner body types and are much less aggressive. Orange males can be nomadic during dry years, and during rainy years tend to occupy small territories. The diet of Urosaurus ornatus consists of a variety of arthropods, such as ants, beetles, true bugs, beetle larvae, and other small arthropods, including scorpions (Asplund 1964, Vitt et al. 1981, Haase 2009).

Zebra-Tailed Lizard

Zebra-tailed lizards are common and widely distributed throughout the Southwestern United States, ranging from the Mojave and Colorado deserts north into the southern Great Basin. Zebra-tailed lizards live in open desert with fairly hard-packed soil, scattered vegetation, and scattered rocks, typically flats, washes, and plains native to dry regions of the western United States and northern Mexico. These lizards are grey to sandy brown, usually with a series of paired dark gray spots down the back, becoming black crossbands on the tail. The underside of the tail is white with black crossbars. Males have a pair of black blotches on their sides, extending to blue patches on their bellies. Females have no blue patches, and the black bars are either faint or completely absent. In breeding season, Zebra-tails get a yellow wash with a bit of orange on the dewlap. Zebra-tailed lizards are diurnal and alert. They rise early and are active in all but the hottest weather. During the hottest times of day, lizards may stand alternately on two legs, switching to the opposite two as needed in a kind of dance. When threatened, they run swiftly with their toes curled up and tails raised over their backs, exposing the stripes. When stopped, they wag their curled tails side-to-side to distract predators. They can even run on their hind legs for short distances.

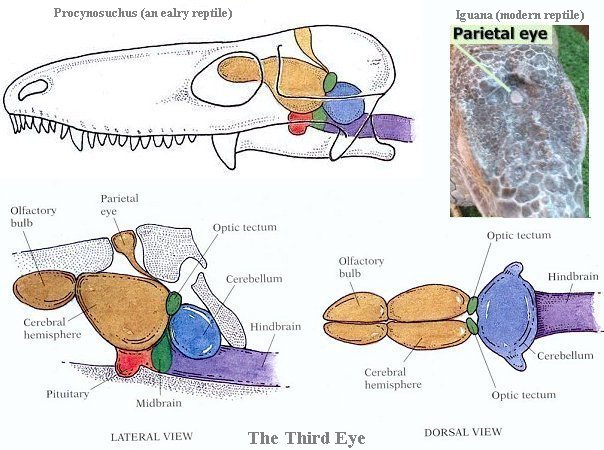

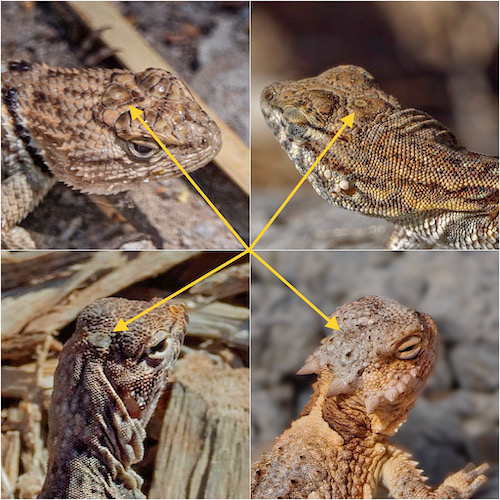

Lizard Third Eye or Parietal Eye

The parietal eye is also known as the third eye, median eye, or pineal accessory apparatus. It is found in two distinct groups of reptiles (order Squamata, suborder Sauria [Lacertillia], and order Rhynchocephalia). This is the remnant of the median eye of provertebrates, which was originally a paired visual organ on the roof of the head. In reptiles, it still appears as an eye-like structure, on the top of the head, situated in a hole beneath the parietal bone. Supporting evidence has shown that dinosaurs had a pineal foramen that was thought to have contained a parietal eye.

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some species of fish, amphibians and reptiles. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhythmicity and hormone production for thermoregulation. The third eye, where present, is always much smaller than the main paired eyes, and, in living species, it is always covered by skin, and is usually not readily visible externally. The parietal eye is a part of the epithalamus, which can be divided into two major parts; the epiphysis (the pineal organ, or pineal gland if mostly endocrine) and the parapineal organ (often called the parietal eye, or third eye if it is photoreceptive). The parietal eye arises as an anterior evagination of the pineal organ or as a separate outgrowth of the roof of the diencephalon. In some species, it protrudes through the skull. The parietal eye uses a different biochemical method of detecting light from that of rod cells or cone cells in a normal vertebrate eye. The parietal eye is found in most lizards, frogs, salamanders, certain bony fish, sharks, and lampreys (a kind of jawless fish). It is absent in mammals, but was present in their closest extinct relatives, the therapsids. It is also absent in turtles and in archosaurs, which includes birds and crocodilians, and their extinct relatives.

How Do I Know If a Lizard Is Male Or Female?

In animal anatomy, a cloaca is the posterior orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles, birds, and a few mammals (monotremes, tenrecs, golden moles, and marsupial moles) have this orifice, from which they excrete both urine and feces; this is in contrast to most placental mammals, which have two or three separate orifices for evacuation. If you’re lucky enough to get your hands on a lizard, check out the back legs and surrounding area. Males lizards often have large “femoral pores,” or little raised bumps, on the bottom side their back legs, which are used to secrete pheromones; females generally either don’t have them or have much smaller ones. Males also store their hemipenes (like many reptiles, male lizards have two pensis) just past their vent, so look for a bulge at the base of the tail. Males also have a pair of enlarged scales near their vent (cloaca). The lizard will effectively hook the female lizard with its Hemipenes. Once hooked in position he will ejaculate into the female. This stage is not the same as humans, there is no bumping and grinding and moaning of pleasure. The male simply stays still on top of the female as he ejaculates. Females and juveniles have some color, but not nearly as bright as males. Also, look for any anatomical “decorations” on the lizard, such as spikes, horns, and dewlaps (flaps on the throat). If you see those, then you are most likely looking at a male lizard. Even if you can’t get a look at the lizard’s belly, there are also behavior clues that help reveal gender. As with birds, the males tend to be more aggressive and demonstrative. And although you’ll often see both males and females doing push-ups (to regulate body temperature), the males are much more energetic.

As always I hope you enjoyed the post and will return for more.

References:

Unusual and Beautiful Geckos, Swifts and Reptiles of Madagascar. Travel to Ear

How Do I Know If a Lizard Is Male Or Female?

Tiger Whiptail (Aspidoscelis tigris)

Chihuahuan Spotted Whiptail Lizard

Southern Desert Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma platyrhinos calidiarum)

There’s Something About Lizard Blood

Yellow-backed Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus uniformis)

Zebra-Tailed Lizard. Bird and Hike

Lizards Around Las Vegas. Bird and Hike

North American Lizards From The Sceloporus Genus

Identifying California Lizards

The pineal gland: Functional connection between melatonin and immune system in birds

Lizards Use Third Eye to Steer by the Sun

What our ancestors’ third eye reveals about the evolution of mammals to warm blood