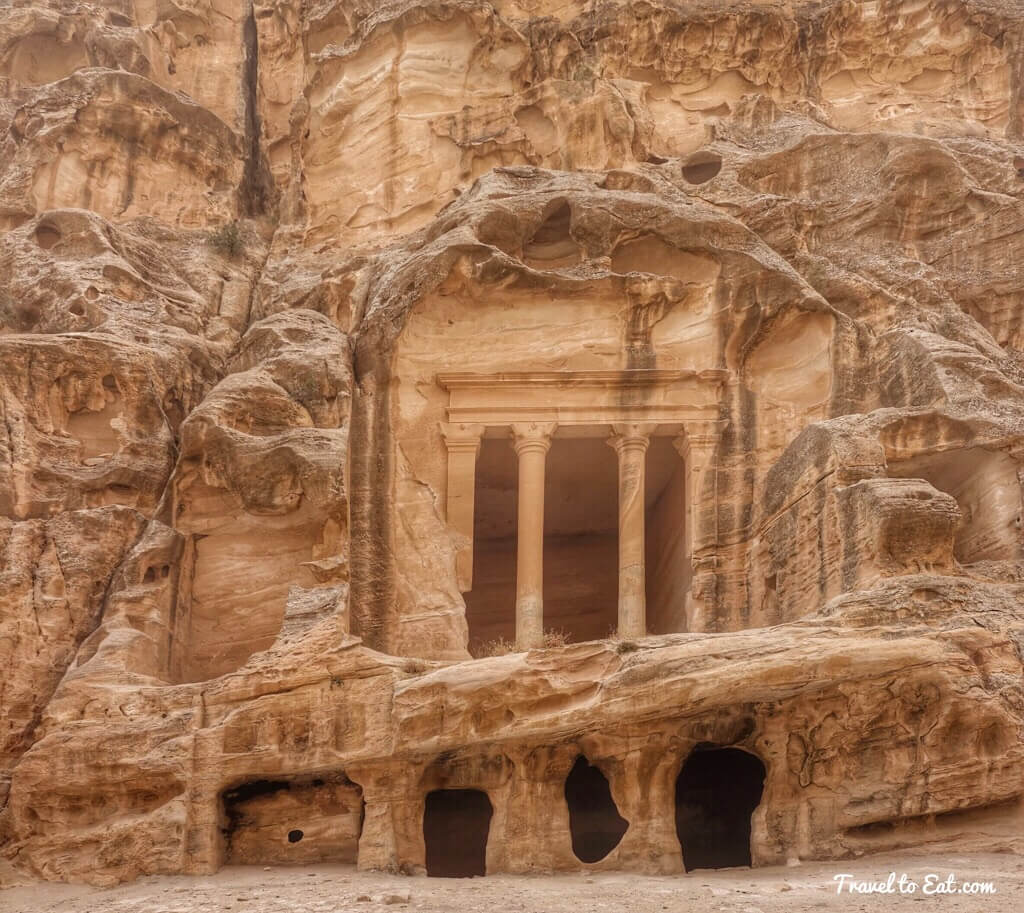

Siq al-Barid (Cold Canyon) is colloquially known as Little Petra and is well worth a visit. It was thought to have served as an agricultural center, trading suburb and resupply post for camel caravans visiting Petra via the King’s Highway. From the car park, an obvious path leads to the 400 meter long Siq (or narrow canyon), which opens out into larger areas. The first open area, near the car park, has a temple pictured above, which archaeologists know little about. A few things are notable, the columns and their caps are neither, Egyptian, Greek or Roman. This seems to be the original architectural style of the Nabetians. I find the style to be very pleasing without unnecessary ornamentation. Little Petra is an archaeological site located a few kilometers north of Petra and the town of Wadi Musa in the Ma’an Governorate of Jordan. Like Petra, it is a Nabataean site, with buildings carved into the walls of the sandstone canyons. As its name suggests, it is much smaller, consisting of three wider open areas connected by a 450-meter (1,480 ft) canyon.

Opposite the temple are some caves, perhaps used as dining rooms for hungry travelers. The pale color of the rocks in this area give the name Al Beidha, meaning the “white one”. A few hundred meters from the Siq Barid a Neolithic village is located, dating back 7000 BC. Around sixty houses have been excavated. The area is popular for hiking, camping and horse riding.

The canyon widens after 400 meters (1,300 ft). In this open area many of the sandstone walls have had openings carved into them; they were used as dwellings. On the south face is a colonnaded triclinium with a projecting pedimented portico that archaeologists believe was used as a temple, though they know very little about it.

When Swiss traveler Jacob Burckhardt became the first Western visitor to Petra since Roman times in 1812, he did not venture to its north, or did not write about it. Later Western visitors to the region likewise seem to have concentrated on the main Petra site. Only in the late 1950s did British archaeologist Diana Kirkbride supplement her excavations at Petra itself with digs in the Beidha area, which included Little Petra, not described as a separate site at the time. Those digs continued until 1983, two years before UNESCO inscribed the Petra area, including Beidha and Little Petra, as a World Heritage Site.

Bir Al-Arayis Is originally a Nabatean Cistern consisting of three consecutive chambers that open to one another, with a total water storage of 1.2 million liters. A rock-cut staircase leads from the entrance of the cistern all the way down to its floor, which is 6 or 7 meters below the entrance level. The interior walls still retain some of the thick layer of plaster commonly found lining Nabatean Cisterns and dams. The Cistern was restored in modern times to serve the community of al Baida.

In 2010, archaeologists made public a discovery from the 1980s. In one of the small biclinia in the western open area, a nearly intact ceiling fresco had been mostly concealed by years of soot from Bedouin campfires and graffiti. Restorers from London’s Courtauld Institute of Art were hired in 2007; the existence of the paintings was announced once their work was complete. The area has since been opened to visiting tourists; it is known colloquially as the Painted House. The frescoes depict, with considerable detail, images related to wine consumption, possibly reflecting worship of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine. They use a variety of paints and materials, including gold leaf and translucent glazes. Three species of grapes have been identified in them, along with two birds (a demoiselle crane and Palestinian sunbird). Other elements include putti playing the flute and fighting off the birds. “The sheer quality of the painting is magical,” said Lisa Sherkede, one of the Courtauld’s restorers. While much Nabataean architecture and sculpture remains, Nabataean painting is very rare today. Courtauld expert David Park says the Little Petra frescoes are, in fact, “the only surviving in situ figurative [Nabataean] wall painting.”

In a small corner of Siq al-Barid, an older Bedouin man played the traditional single stringed Rebab with a horsehair bow. Though many variations exist, the rebab consists of a small, usually rounded body, the front of which is covered in a membrane such as parchment or sheepskin. There is a long thin neck with a pegbox at the end and there are one, two or three strings. There is no fingerboard. The instrument is held upright, either resting on the lap or on the floor. The rebab became a favourite instrument of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, and could be heard everywhere from the palace to the tea house.. The arab orchestra or group uses many drones, unisons and parallel octaves, giving a stirring, powerful sound, but it is mostly modal with little in the way of chordal movement. The rebab, though valued for its voice-like tone, has a very limited range (little over an octave), and was gradually replaced throughout much of the arab world by the violin and kemanche.

References:

Little Petra: http://sleeplessinamman.com/littlepetra/

Nabetea: http://nabataea.net/beidha.html

Rebab: http://www.fiddlingaround.co.uk/med/

Painted Biclinium: http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/restored-siq-al-barid-wall-painting-unveiled

Painted Biclinium: http://www.theguardian.com/science/2010/aug/22/hellenistic-wall-paintings-petra