The Library of Congress was established by an act of Congress in 1800 when President John Adams signed a bill providing for the transfer of the seat of government from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington. Behind the creation of the American republic was another republic, which made the Constitution thinkable. This was the Republic of Letters, an information system powered by the pen and the printing press, a realm of knowledge open to anyone who could read and write, a community of writers and readers without boundaries, police, or inequality of any kind, except that of talent. Like other men of the Enlightenment, the Founding Fathers believed that free access to knowledge was a crucial condition for a flourishing republic, and that the American republic would flourish if its citizens exercised their citizenship in the Republic of Letters. The original library was housed in the then new Capitol until August 1814, when invading British troops set fire to the Capitol Building, burning and pillaging the contents of the small library. Within a month, retired President Thomas Jefferson offered his personal library as a replacement. Jefferson had spent 50 years accumulating books, “putting by everything which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare and valuable in every science.” His library was considered to be one of the finest in the United States and formed the nucleus of the Library of Congress.

On December 24, 1851, the largest fire in the Library's history destroyed 35,000 books, about two–thirds of the Library's 55,000 book collection, including two–thirds of Jefferson's original transfer. In 1852, Congress quickly appropriated $168,700 to replace the lost books, but not for the acquisition of new materials. Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Librarian of Congress from 1864 to 1897, applied Jefferson's philosophy on a grand scale and built the Library into a national institution. Spofford was responsible for the copyright law of 1870, which required all copyright applicants to send to the Library two copies of their work. This resulted in a flood of books, pamphlets, maps, music, prints, and photographs. Facing a shortage of shelf space at the Capitol, Spofford convinced Congress of the need for a new building, and in 1873 Congress authorized a competition to design plans for the new Library. In 1886, after many proposals and much controversy, Congress authorized construction of a new Library building in the style of the Italian Renaissance in accordance with a design prepared by Washington architects John L. Smithmeyer and Paul J. Pelz who finished it in 1897. It was known as the Library of Congress (or Main) Building until June 13, 1980, when it was renamed for Thomas Jefferson.

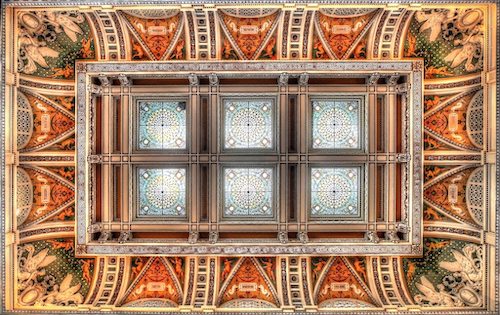

The building's elaborate beaux arts decoration, which combines sculpture, mural painting, and architecture on a scale unsurpassed in any American public building, was possible only because General Casey and Bernard Green lived up to their reputations as efficient construction engineers, completing the building for a sum substantially less than that appropriated by Congress. When it became apparent in 1892 that funds for “artistic enrichment” would be available out of the original appropriation, Casey and Green seized the opportunity and turned an already remarkable building into a cultural monument. They were anxious to give American artists an opportunity to display their talents, and ultimately they commissioned no less than 42 American sculptors and painters “to fully and consistently carry out the monumental design and purpose of the building.” In the famous main reading room, from the Visitors' Gallery, eight large statues can be seen above the giant marble columns that surround the reading room. They represent eight categories of knowledge, each considered symbolic of civilized life and thought. The symbolic statues are: Philosophy, by Bela Lyon Pratt; Art, by Francois M.L. Tonetti-Dozzi (after sketches by Augustus St. Gaudens); History, by Daniel Chester French; Commerce, by John Flanagan; Religion, by Theodore Baur; Science, by John Donoghue; Law, by Paul Wayland Bartlett; and Poetry, by John Quincy Adams Ward. Edwin Howland Blashfield's murals, which adorn the dome of the Main Reading Room, occupy the central and the highest point of the building and form the culmination of the entire interior decorative scheme. The round mural set inside the lantern of the dome depicts Human Understanding, looking upward beyond the finite intellectual achievements represented by the twelve figures in the collar of the dome.

Even though the main reading room is big and impressive, the front foyer or great room is all of that and much more. The arcade at the center of the east side of the Great Hall takes the form of a triumphant arch commemorating the construction of the building. The words LIBRARY OF CONGRESS are inscribed in tall gilt letters above the arch. A marble tablet inscribed with the names of the building's construction engineers and architects is part of the parapet immediately above. The tablet is flanked by two majestic eagles. The names of ten great authors can be seen on tablets above the Great Hall's semicircular latticed windows in the vaulted cove of the ceiling. Beginning on the east and proceeding clockwise, the names are DANTE, HOMER, MILTON, BACON, ARISTOTLE, GOETHE, SHAKESPEARE, MOLIERE, MOSES, and HERODOTUS. The two great staircases flanking the Great Hall are embellished by elaborate and varied sculptural work by Philip Martiny. At the base of each is a bronze female figure wearing classic drapery and holding a torch of knowledge. The cherubs in the ascending railing of each staircase represent “the various occupations, habits, and pursuits of modern life.” The series begins at the bottom with the figure of a stork. The flooring in the entrance vestibule is made of white Italian marble, with bands and geometric patterns of brown Tennessee marble. Modeling and incised brass inlays have been added to the marble floor within the Great Hall. As your eye travels up the short piers to the gilt ceiling you see the paired figures of Minerva, created by Herbert Adams as the “Minerva of War” and the “Minerva of Peace” and placed atop each marble pillar at the base of the double staircases. “Minerva of War” grasps a short sword in one hand and holds aloft the torch of learning in the other; “Minerva of Peace” holds a globe, which symbolizes the universal scope of knowledge, and a scroll. This room is so richly decorated that I cannot describe everything but a visit to “On These Walls” listed in the references will answer many questions.

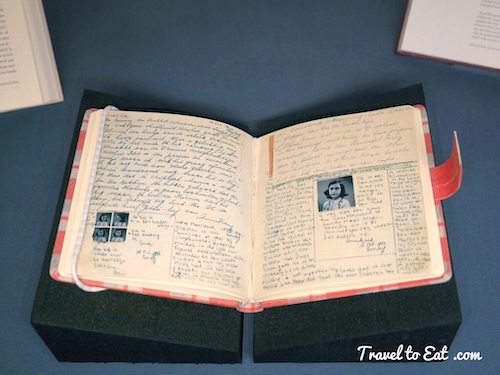

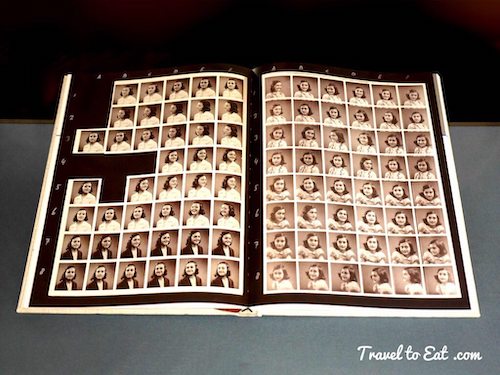

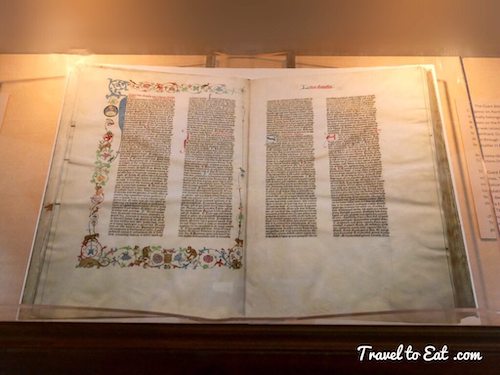

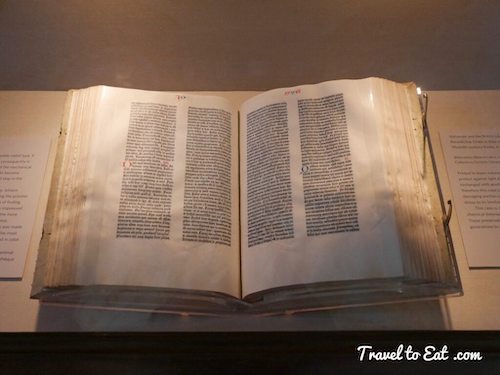

The Library of Congress, spurred by the 1897 reorganization and move, began to grow and develop more rapidly. Spofford's successor John Russell Young, though only in office for two years, overhauled the Library's bureaucracy, used his connections as a former diplomat to acquire more materials from around the world, and established the Library's first assistance programs for the blind and physically disabled. Young's successor Herbert Putnam held the office for forty years from 1899 to 1939, entering into the position two years before the Library became the first in the United States to hold one million volumes. Today the collections of the Library of Congress include more than 32 million cataloged books and other print materials in 470 languages; more than 61 million manuscripts; the largest rare book collection in North America, including the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence and a Gutenberg Bible (one of only three perfect vellum copies known to exist) and much more. In the mid-1990s, under Billington's leadership, the Library of Congress began to pursue the development of what it called a “National Digital Library,” part of an overall strategic direction that has been somewhat controversial within the library profession. In late November 2005, the Library announced intentions to launch the World Digital Library, digitally preserving books and other objects from all world cultures. The Library of Congress states that its collection fills about 838 miles (1,349 km) of bookshelves, while the British Library reports about 388 miles (624 km) of shelves. The Library of Congress holds more than 155.3 million items with more than 35 million books and other print materials, against approximately 150 million items with 25 million books for the British Library.

[mappress mapid=”69″]

References:

Library Website: http://www.loc.gov/

Congressional Website: https://www.congress.gov/

National Digital Library: http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2010/oct/04/library-without-walls/

On These Walls: http://www.loc.gov/loc/walls/jeff1.html