I thought that because I like to write about topics in archaeology, I would devote a few posts to the various dating schemes used by archaeologists beginning with the Neolithic, the end of the Stone Age and just prior to the beginning of metallurgy in the Levant, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Turkey and Mesopotamia. The worldwide beginning of the Neolithic culture is considered to be in the Levant (Jericho, modern-day West Bank) about 10,200–8,800 BC. It developed directly from the Natufian culture in the region, whose people pioneered the use of wild cereals, which then evolved into true farming and animal husbandry. The Metropolitan Museum has a beautiful collection from just this time period and location and I thought I would share. The Neolithic is known as the time humanity transitioned from hunter-gatherers to a more sedentary farming behavior. Several markers of this transition have proven to be more complicated than originally imagined. Pottery, a marker of sedentary life that produced relatively heavy objects is both older and younger than first imagined. Apparently ceramic objects were discovered and forgotten on multiple occasions in the period from 30,000 to 10,000 years BC. In fact, the Halif Culture in Syria and northern Mesopotamia only started making actual pottery around 5,500 BC. So the beginning of the Levant Neolithic Period began in the pre-pottery era. Another marker of sedentary life might be buildings. The evidence of temples built at Göbekli Tepe by hunter gatherers from at least 11,000 BC suggests that while the site formally belongs to the earliest Neolithic (PPNA), up to now no traces of domesticated plants or animals have been found. The inhabitants are assumed to have been hunters and gatherers who nevertheless lived in villages for at least part of the year. Probably the best indicator of the beginning of the Neolithic Period may be the use of grains to make bread although even that is blurred by Ohalo.

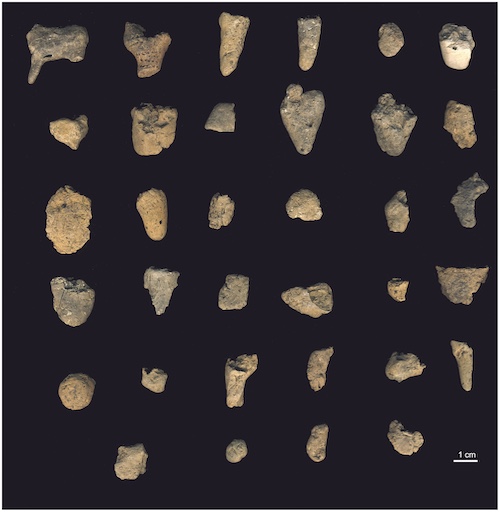

Vela Spila is a large, limestone cave on Korčula Island, in the central Dalmatian/Croation archipelago. Excavations have taken place there sporadically since 1951, and there is evidence of occupation on the site during the Upper Palaeolithic period, roughly 20,000 years ago, through to the Bronze Age about 3,000 years ago. Ceramic artifacts from the Pleistocene are extremely rare. Ceramic hearths from Klisoura Caves in Greece have been dated to between 34,000 and 32,000 years old. The oldest known ceramic objects considered to be artistic rather than functional are ‘Pavlovian’ figurines from Moravia in the Czech Republic, and neighboring areas, dated to between 31,000 and 27,000 years old. A single anthropomorphic figurine is known from Maina in southern Siberia, which is believed to be about 27,400 years old, another ceramic figurine from Tamar Hat in Algeria is thought to be between 20,600 and 19,800 years old. Fragmentary ceramic objects from Kostenki in Russia have been dated to between 25,300 and 21,930 years old. A number of fragmentary ceramic objects from Yuchanyan Cave in Hunan Province, China, have been dated to between 21,000 and 13,800 years old. Large clay statues from Tuc d’Audoubert and Montespan Cave in France have been dated as 15,000 and 20,000 years old, respectively. Twelve thousand year-old pottery is known from Japan; the Japanese are considered to have been continuously making ceramic objects from this point. Thus the “Neolithic package” of sedentary farming occurs both before pottery and after pottery in China, Japan, and the Levant.

Ohalo is the common designation for the archaeological site Ohalo II in the vicinity of the Sea of Galilee, and one of the best preserved hunter-gatherer archaeological sites of the Last Glacial Maximum, having been radiocarbon dated to around 19,400 BP (17,400 BC). The site is significant because of the numerous fruit and cereal grain remains preserved therein, (intact ancient plant remains being exceedingly rare finds due to their quick decomposition). Just 13 species of fruit and cereal make up about half of the total number of seeds found in the area; these include acorns, brome grains (Bromus pseudobrachystachys), wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) and millet grass grains (Piptatherum holciforme), just to name a few. This suggests a marked preference of certain species of edible plants. A seed of particular interest comes from the Rubus fruit, which was fragile, difficult to transport, and preferably eaten immediately after collection. Most importantly, the extremely high concentration of seeds clustering around the grinding stone in the northern wall of Hut 1 led archeologist Ehud Weiss to believe that humans at Ohalo II processed the grain before consumption. The Kebaran culture (18,000 to 12,500 BC) is the last Upper Paleolithic phase of the Levant (Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine). The Kebarans were characterized by small, geometric microliths, and were thought to lack the specialized grinders and pounders found in later Near Eastern cultures although Ohalo technology may have been transmitted.

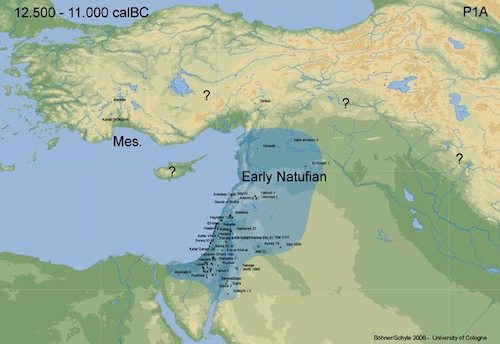

The term “Natufian” was coined by Dorothy Garrod who studied the Shuqba cave in Wadi an-Natuf, in the western Judean Mountains, about halfway between Tel Aviv and Ramallah. Natufian culture (13,000 to 9,800 BC) was unusual in that it was sedentary, or semi-sedentary, before the introduction of agriculture. The Natufian communities are possibly the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. There is some evidence for the deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture, at the Tell Abu Hureyra site, the site for earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. Generally, though, Natufians made use of wild cereals. Animals hunted included gazelles and marine life. The Natufians are also the first documented Levantine group to have produced artistically decorated utilitarian objects such as pottery and ostrich-egg vessels. There is no reason to assume that stone-built architecture is necessarily more durable than the structures than the Ohalo II huts, especially since the walls of Natufian houses are rarely over 2–3 courses in height and may have also had organic superstructures. It is also worth noting that at one of the best-studied Natufian sites in southwest Asia, Tell Abu Hureyra, where year-round occupation and cereal cultivation are said to have first appeared, stone buildings are apparently absent (albeit the Natufian deposits are comparatively small exposures) and with pit and post-hole dwellings present instead. Unlike today, trees yielding hard-shell fruits were part of the former landscape of the Southern Levant, Greece and in fact the entire Mediterranean. Among these, oaks were one of the most prominent features of the Mediterranean woodlands, covering large parts of the landscape. Nevertheless, their possible importance as a food source in past economies of the Southern Levant has been underestimated in comparison to other plant resources. Furthermore, the appearance of stone pounding and grinding tools (frequently mentioned in ethnographic accounts as acorn processing tools) in the Epipalaeolithic and the Early Neolithic has been mostly seen as associated with cereal processing and the transition to agriculture based economies. But there is a suggestion that they were used for processing of acorns into flour.

Just before the introduction of pottery in the Levant, softer stone would have been used to make bowls, vessels and cult figurines as seen above. Although the potters wheel was thought to be invented between 6000 and 4000 BC, these bowls look suspiciously symmetrical, suggesting the use of a wheel/lathe to create them. In particular, the footed granite bowl would have been extremely hard to make without a lathe. In fact the potters wheel might have been the innovation that began the use of ceramics rather than just a useful tool.

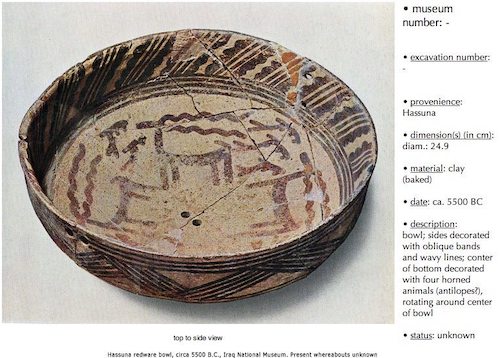

The earliest history of pottery production in the Near East can be divided into four periods, namely: the Hassuna period (7000-6500 BC), the Halaf period (6500-5500 BC), the Ubaid period (5500-4000 BC), and the Uruk period (4000-3100 BC). Many early ceramics were hand-built using a simple coiling technique in which clay was rolled into long threads that were then pinched and beaten together to form the body of a vessel. In the coiling method of construction, all of the energy required to form the main part of a piece is supplied indirectly by the hands of the potter. The invention of the potter’s wheel in Mesopotamia sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 BC revolutionized pottery production. Specialized potters were then able to meet the expanding needs of the world’s first cities.

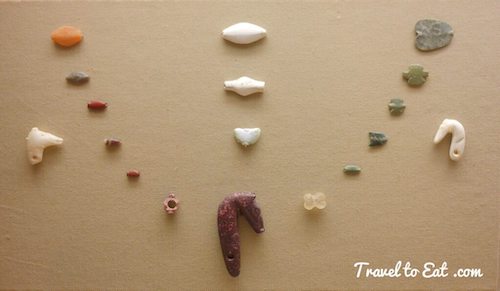

In the period 6500–5500 BC, a farming society emerged in northern Mesopotamia and Syria which shared a common culture and produced pottery that is among the finest ever made in the Near East. This culture is known as Halaf, after the site of Tell Halaf in northeastern Syria where it was first identified. The Halaf potters used different sources of clay from their neighbors and achieved outstanding elaboration and elegance of design with their superior quality ware. Some of the most beautifully painted polychrome ceramics were produced toward the end of the Halaf period. This distinctive pottery has been found from southeastern Turkey to Iran, but may have its origins in the region of the River Khabur (modern Syria). How and why it spread so widely is a matter of continuing debate, although analysis of the clay indicates the existence of production centers and regional copying. It is possible that such high-quality pottery was exchanged as a prestige item between local elites. The Halaf culture also produced a great variety of amulets and stamp seals of geometric design, as well as a range of largely female terracotta figurines that often emphasize the sexual features. Note the similarities between the Met, Louvre, and British Museum figures showing a distinct stylized image of the Venus figurine from the pantheon of different representations of women of the preceding millenia. The Halaf culture was eventually absorbed into the so-called Ubaid culture, with changes in pottery and building styles.

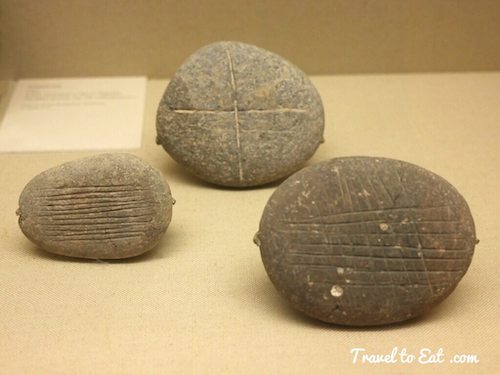

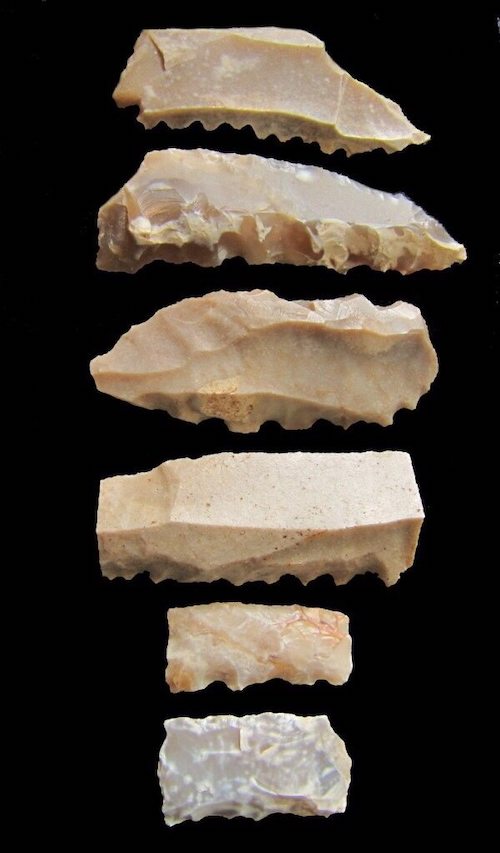

The Yarmukian culture (6400-6000 BC) was a Neolithic culture of the ancient Levant. It was the first culture in prehistoric Israel and one of the oldest in the Levant to make use of pottery. The Yarmukian derives its name from the Yarmouk River which flows near its type site at Sha’ar HaGolan, a kibbutz at the foot of the Golan Heights. About 300 art objects were found at Sha’ar HaGolan, making it the main center of prehistoric art in Israel and one of the most important in the world. One of the houses yielded approximately 70 figurines made of stone or fired clay. No other single building of the Neolithic period has yielded that many prehistoric figurines. Among the outstanding art objects from Sha’ar HaGolan are figurines in human form made of fired clay or carved on pebbles. The overwhelming majority are female images, interpreted as representing a goddess. The clay figurines are extravagant in their detail, giving them a surrealistic appearance, while the pebble figurines are minimalist and abstract in form. The domestication of animals (c. 8000 BC) resulted in a dramatic increase in social inequality. Possession of livestock allowed competition between households and resulted in inherited inequalities of wealth. The Yarmukian, known from some 20 sites in the southern Levant is famous for its “Coffeee beans eyes” clay figurines. The Yarmukians were the first in this part of the world who used pottery. They built up limited semi-subterannian rounded huts at some sites, but at Sha’ar Hagolan, re-excavated after the 1990s, rectangular residental structures were found , including a courtyard house. The excavations uncovered a central street about 3 m wide, paved with pebbles set in mud, and a narrow winding alley 1 m wide. These are among the earliest streets built by man and structures that can be interpreted as “public buildings”. Beside different arrowpoints, denticulated flint sickleblades are the hallmarks of the Yarmukian complex in Israel.

This has been a long post so I think a little conclusion is warranted. The transition from the Stone Age to the Neolithic is far more complicated than we might have thought. Pottery and ceramics appear both before and after the transition to sedentary farming life. Perhaps due to the many climatic changes, inventions of farming, animal husbandry, pottery or housing were often discovered and then forgotten in the next cold spell. The reason the Levant survived these many changes is that this area, unlike the desert conditions of today, remained a relative sanctuary of green forests and grasslands through both hot and cold periods. Additionally, the “Fertile Crescent” was at a crossroad of trade between the east and west, making materials such as basalt and inventions such as the guinea fowl (chickens) available for the new lifestyle. I now believe the “Neolithic Revolution” occurred over several millenia rather than from a single discrete event. I believe the single greatest innovation of this time was the realization that the innumerable tiny grains of the grasslands held more nutrition than the much larger root vegetables.

References:

17,500 Year old Ceramics: http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/archaeologists-uncover-palaeolithic-ceramic-art

Harvard Ohalo: http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/2004/09.30/08-oven.html

Lisa Maher Ohalo Settlements: http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0031447

Mesolithic and Neolithic Acorns: http://oldeuropeanculture.blogspot.ie/2014/11/acorns-in-archaeology.html

Natufian Culture: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/anthropology/v1007/baryo.pdf

Museum of Yarmukian Culture: http://www.elmulgolan.co.il/en/museum-of-yarmukian-culture/

Hassuna Culture: http://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/iraq05-034.html

Rebecca Farbstein: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0041437

Warming and Cold Periods: http://www.esd.ornl.gov/projects/qen/nercEUROPE.html

Ancient Levant Maps: http://context-database.uni-koeln.de/map.php?mapM=1&AN=1&Zeit=12