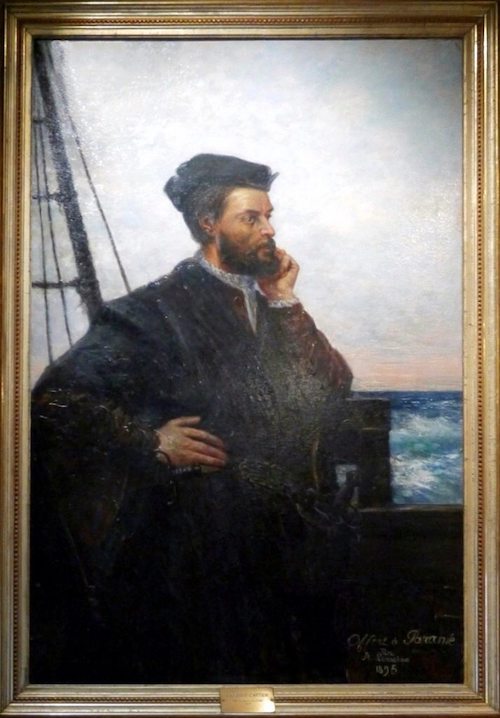

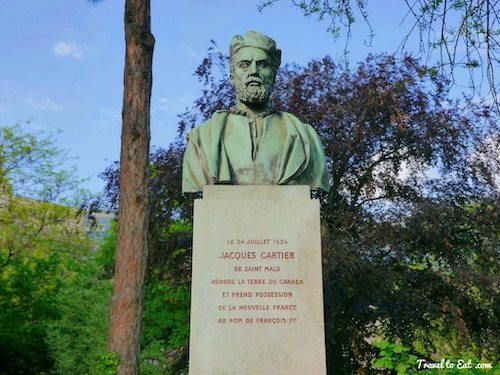

Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) was the first French Explorer to explore the New World. He explored what is now Canada and set the stage for the great explorer and navigator Samuel de Champlain to begin colonization of Canada. Cartier was the first European to discover and create a map for the St. Lawrence River. In 1838, the painter François Riss received an order by the city of St Malo to produce a portrait of Jacques Cartier (1491-1557). It was reproduced in 1846 by the painter Louis-Félix Amiel in Quebec City. The original painting of the imagined Cartier by Riss was destroyed in a fire at the old town hall in 1944. This version is one of many replicas of the lost work. It was executed in 1895 by the librarian of the city of Saint-Malo, Auguste Lemoine (1850-1908) for the the city of Paramé and now hangs in the St Malo civic history museum. There are no known contemporary portraits of Cartier.

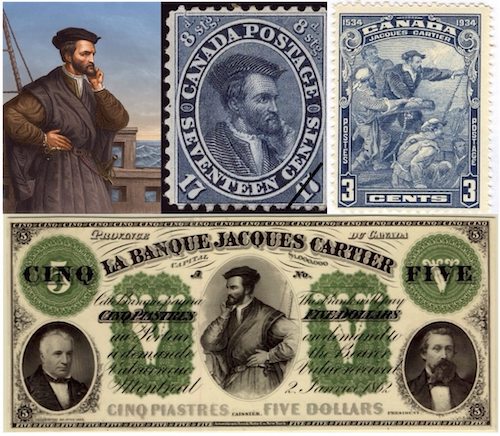

This picture had been copied by Théophile Hamel in Canada and was widely disseminated in the form of lithographs from 1847 and Canadian Postal stamps in 1859 and 1934. Mr. George Arthur Gundersen designed the Jacques Cartier stamp that was issued in 1934 (above, top/right). Bank notes also reproduced the image as seen in this 1862 Montreal banknote example.

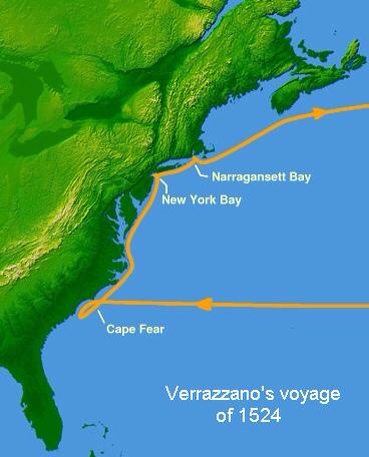

France’s adventure in the Americas began in the 16th century, when King François I was persuaded by a group of Florentine bankers living in Lyon to commission an Italian, Giovanni da Verrazano (sometimes spelled Verrazzano), to explore the coasts of the continent discovered by Christopher Colombus at the end of the previous century. He set out from Dieppe in 1524 with four boats, two sunk in a storm, another was sent back with Spanish booty leaving him the the flagship La Dauphine. Prior to his first major expedition, it was believed that Jaques Cartier had travelled to the Americas, possibly with Verrazano. Of the crew of 50, the only one who is known apart from Verrazzano himself was his brother Girolamo da Verrazzano, who was a mapmaker. His 1529 world map was one of the two first maps to show Verrazano’s discoveries (the other was the 1527 Maiollo map presented below). King François needed money, he did not have to pay for the expedition and François had no inhibitions over poaching on the Portuguese or Spanish preserve; in fact, he was incensed at the arrangement between those two nations and at the Pope who had divided the world between them.

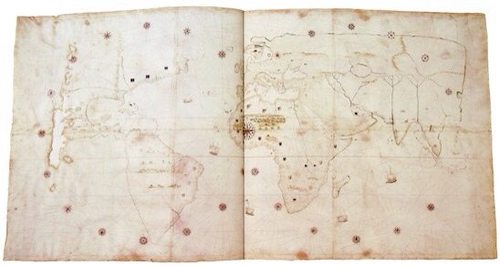

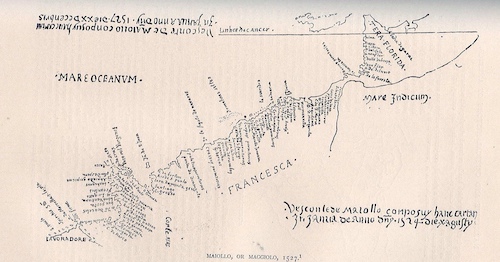

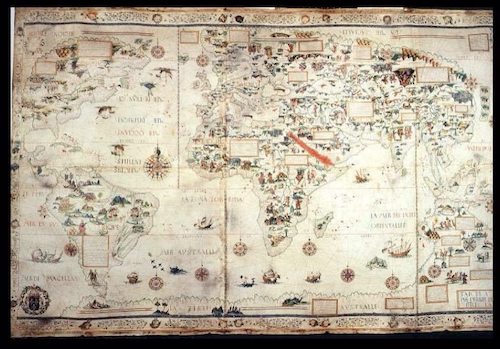

Verrazano was not much of an explorer, he preferred to anchor out to sea and avoided going inland at all (he was eaten by cannibals in 1528 after going to land in a small boat on his third voyage). He sailed up the coast looking for a passage that would take him west through the continent. He reached the mouth of the Hudson River in New York Bay, and wrote “we found a very pleasant situation amongst some steep hills …” After rowing ashore in a small boat Verrazano had a brief encounter with a group of Native Americans. The friendly natives welcomed the strangers, giving them gifts and food. Verrazano and his crew did not stay long however, due to uncertain weather. A bridge connecting Long Island and Staten Island today is named the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, after this early explorer. Note the large body of water named on the map Mare Verrazzano in the middle of North America. In the far north is an English shield and an inscription that the land was discovered by the English on Terra Laboradoris. This inscription is particularly important as it records the opinion prevalent in 1529 that the landfall of the Cabots was far to the north in Labrador. Also note there appears to be an open Northwest Passage. French flags of solid blue are seen on on Nova Gallia Sive Iycatanet, that part of the coast visited by Verrazzano. Verrazzano has introduced the name Norumbega (here, in the form Noranbega, applied to a river), by which the New England region was known throughout the 16th century.

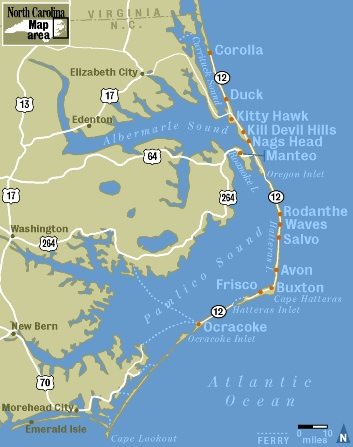

After passing Cape Fear and Cape Lookout, Verrazzano sailed the long reaches outside the Outer Banks of North Carolina. He sighted Cape Hatteras and continued northward, traveling the 150 miles around Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds. The large body of water inside the Outer Banks was visible from the ship but no inlet was found. Verrazano believed that the sea that lay behind it, in reality Pamlico Sound, was the Pacific. Thus North America at this point seemed nothing more than a rather long, extremely narrow isthmus. This mistake led mapmakers, starting with Maggiolo and Girolamo Verrazzano, to show North America as almost completely divided in two, the two parts just connected by a narrow piece of land on the east coast. Verrazono wrote:

. . . where was found an isthmus a mile in width and about 200 long, in which, from the ship, was seen the oriental sea between the west and north. Which is the one, without doubt, which goes about the extremity of India, China and Cathay. We navigated along the said isthmus with the continual hope of finding some strait or true promontory at which the land would end toward the north in order to be able to penetrate to those blessed shores of Cathay …

This particular map attracted little attention until it was discovered in 1881 by Desimoni. The date of the map had been altered to 1587 from the true original date of 1527. The author, Vesconte de Maiollo, who died in 1551, was a distinguished portolan (nautical) chart maker. In 1519 Maiollo was made Magister cartarum pro navigando of the Republic of Genoa. This map seems to detail the voyage of Verrazano and has several interesting features. First it is oriented with west at the top, Florida in the upper right, Lavoradoe in the lower left (attributed to the British). Corte Reale is also noted in the lower left, a reference to the Portuguese fisherman from the Canary Islands that I will discuss in the next post. Mare Indicum suggests that the eastern coast of North America is just a thin strip of land blocking access to the Pacific Ocean.

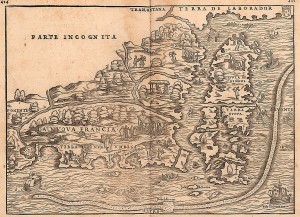

Jacques Cartier was born on December 31, 1491 in the port of Saint Malo, Brittany. He belonged to a family of mariners and became very respectable when he married Mary Catherine des Granches, a member of a family of well-known ship owners. In 1534, the year the Duchy of Brittany was formally united with France in the Edict of Union, Cartier was introduced to King Francis I by Jean le Veneur, bishop of Saint-Malo and abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel. Le Veneur cited voyages to Newfoundland and Brazil as proof of Cartier’s ability to “lead ships to the discovery of new lands in the New World”. This is the first printed map to focus on New England and New France. The geographic information is based on the 1524 voyage of Giovanni Verrazzano. His avoidance of the dangerous coastline and shoals from Cape Cod to Maine created the “information gap” that gives this map its confused, foreshortened look. Nonetheless, it clearly states French claims to the St. Lawrence region and emphasizes French fishing activity in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Although Ramusio discusses the explorations of Jacques Cartier in his book, no Cartier information shows on this map.

Grande Hermine was the name of the ship used by Jacques Cartier. The Grande Hermine was a small ship of sixty tons. Another small ship accompanied the Grande Hermine. Both ships had a crew of thirty men. On April 20, 1534, Cartier set sail under a commission from the king, hoping to discover a western passage to the wealthy markets of Asia.

On his first voyage, he crossed the Atlantic in 20 days. He explored parts of Newfoundland, the areas now the Canadian Atlantic provinces and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. During one stop at Îles aux Oiseaux (Islands of the Birds, now the Rochers-aux-Oiseaux federal bird sanctuary, northeast of Brion Island in the Magdalen Islands), his crew slaughtered around 1000 birds, most of them great auks (now extinct). While exploring he came across two Indian tribes the Mi’kmaq and the Iroquois at Gaspé Bay. Initially relations with the Iroquois were positive as he began to establish trade with them. However, Cartier then planted a large cross and claimed the land for the King of France. The Iroquois understood the implications and began to change their mood. In response Cartier kidnapped two of the Chief’s sons. The Iroquois Chief and Cartier agreed that the sons could be taken as long as they were returned with European goods to trade.

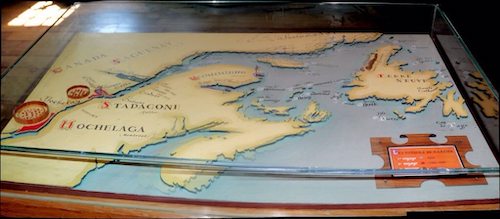

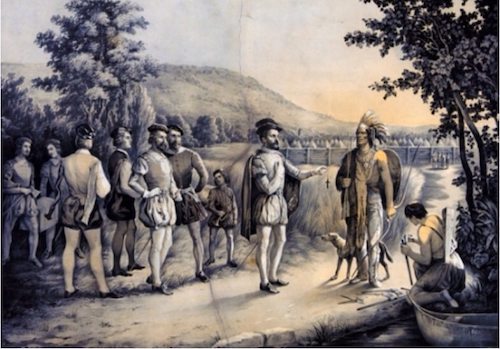

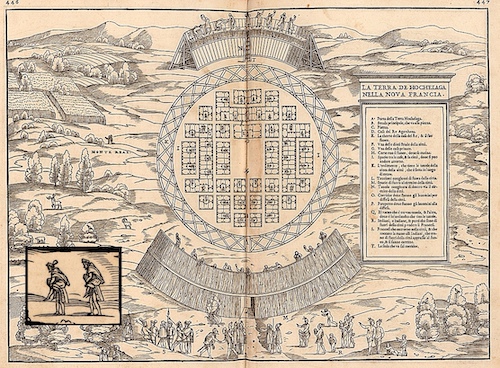

In May of 1535, Cartier set sail from France with 3 ships, 110 men, Chief Donnacona’s 2 sons Dom Agaya and Taignoagny (who Cartier had kidnapped the previous year), and instructions to find the Iroquoian villages of Stadacona and Hochelaga. On September 7, Cartier arrived at l’Île d’Orléans near Stadacona (present-day Quebec). He was met by Chief Donnacona, who was relieved to see his sons, but the gifts from the French King were not enough to erase the reservations he felt following his sons’ kidnappings. Cartier left his main ships in a harbor close to Stadacona, and used his smallest ship to continue up-river and visit Hochelaga (now Montreal) where he arrived October 2, 1535.

Hochelaga was far more impressive than the small and squalid village of Stadacona, and more than 1,000 Iroquoians came to the river edge to greet the Frenchmen. On October 2, 1535, Cartier landed on a large island which resembled that described by Chief Donnacona’s sons, Dom Agaya and Taignoagny. Rowing to shore, Cartier soon found that the land had been cultivated with corn which, he had learned, would not grow in the wild. Nearby, at the base of a mountain, Cartier discovered the Iroquoian village of Hochelaga (present-day Montreal). The Iroquoians were eager to meet with Cartier. Gifts were exchanged and a feast was arranged.

During their discussions, Cartier was introduced to a cultivated plant which, when dried and pounded into small pieces, was then packed into ‘pipes’ and set alight. Cartier had discovered tobacco. Take a careful look at the pipe shown above from the Saint Malo Historical Museum. It is dated 1550 and Cartier’s expeditions returned in 1536 and 1542. This may very well be the oldest European pipe in existence and may have been from the Iroquois Indians.

Before returning to Stadacona, Cartier climbed the mountain which he named Mount Réal (Mount Royal), although it is unknown whether the name was given in honour of the King of France or from the sheer majesty of the mountain. From its summit, Cartier noted that he could see the land and river for many kilometres. He immediately realized that no enemy could approach without being seen. With such a view and potential defensibility, the mountain would be an ideal spot for settlement. However, he could also see the impassable rapids at Lachine and realized that his hoped-for route to the Pacific had come to a disappointing end. The rapids were named Lachine after the French name for China, La Chine, which Cartier thought might be just beyond the rapids.

Over the winter, Stadacona was hit by disease and scurvy. Whether or not the sickness was brought on by the French is unknown, but the French were blamed nonetheless. Donnacona ceased all contact. By December, 50 natives had died and Cartier’s crew were also suffering terribly from scurvy. In February almost the entire company were affected by the disease and as many as 25 of them died before the survivors learned from Dom Agaya (the chiefs son) that the bark of a white spruce tree boiled in water and drunk as a tea would cure the disease. Cartier and his men used an entire white spruce to concoct the remedy.

With friendships renewed, Donnacona told Cartier of the land of Saguenay which was rich with gold and jewels, where white men lived and grew spices of many varieties. Cartier asked the chief to return with him to France and tell the King, thus ensuring a third voyage, but Donnacona declined and gave Cartier a ‘gift’ of 4 children to go in his stead. In May of 1536, Cartier forcibly kidnapped Chief Donnacona, his sons Dom Agaya and Taignoagny, and 3 other natives and took them back to France. In France, Donnacona met with the King and told him of ‘the land of Saguenay beyond the towering waterfalls’ where the land was filled with wealth and where white men lived and spices grew in abundance. Before Jacques Cartier could return the Iroquoians to Canada, all of them except for one of the young ‘gift’ girls died. Chief Donnacona died in either 1540 or 1541 and was buried in France.

On returning to Stadacona in 1541, Cartier met with the new Iroquoian chief Agona. He explained that Donnacona had grown ill and had died in France. He was buried there. He then lied and told the chief that the others who had accompanied him to France had become rich and had decided to marry and to remain there. The natives were understandably outraged and Cartier decided it best to abandon the fort at Stadacona. He located a new site at the mouth of the Rivière de Cap-Rouge, 14 kilometres (9 miles) away from Stadacona, and built a new fort. He named the settlement Charlesbourg-Royal, which would become the first French settlement in North America. Within 2 years, Charlesbourg-Royal would be abandoned. In Spring of 1542, Cartier abandoned Charlesbourg-Royal and set out for France with a supply of what he believed was gold and diamonds gathered from the shores of the St. Lawrence River which turned out to be worthless pyrite and quartz. Exploration was suspended and Cartier retired to St Malo. On August 18, 2006, Quebec Premier Jean Charest announced that Canadian archaeologists had discovered the precise location of Cartier’s lost first colony of Charlesbourg-Royal.

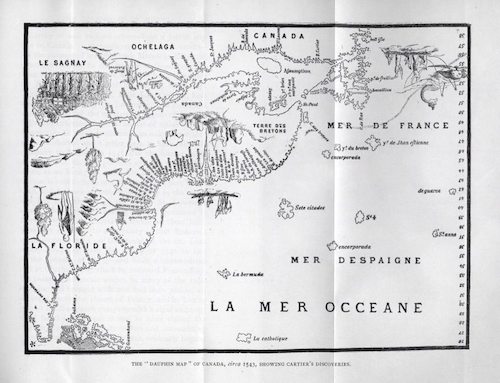

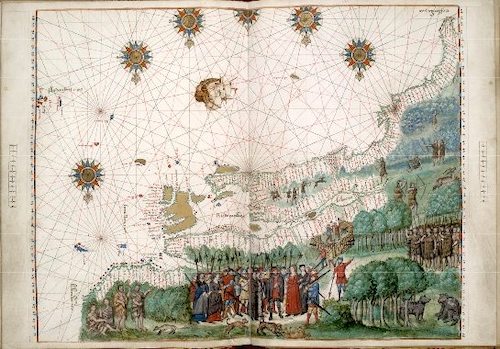

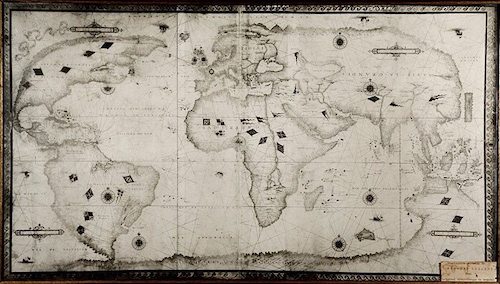

Cartier was the first to document the name Canada to designate the territory on the shores of the St-Lawrence River. The name is derived from the Huron-Iroquois word “kanata”, or village, which was incorrectly interpreted as the native term for the newly discovered land. Cartier used the name to describe Stadacona, the surrounding land and the river itself. And Cartier named “Canadiens” the inhabitants (Iroquoians) he had seen there. Thereafter the name Canada was used to designate the small French colony on these shores, and the French colonists were called Canadiens. Between 1536 and 1566, a series of maps of the world were published by various cartographers in the French town of Dieppe, a centre for map production in Europe. The first is known as the Dauphin map as it was given to the the Dauphin, the Crown Prince of France as a gift. These were large hand-produced maps, commissioned for wealthy and royal patrons, including Henry II of France and Henry VIII of England. The Dieppe school of cartographers included Pierre Desceliers, Johne Rotz, Guillaume Le Testu, Guillaume Brouscon and Nicolas Desliens. There appears to have been an illicit trade in information with Portuguese cartographers, the Dieppe School was at least very influenced by the Portuguese.

Despite the failure of the Charlesbourg-Royal settlement, Cartier’s explorations along the St. Lawrence River opened the interior of Canada to French control. In 1608, the legendary Samuel de Champlain established France’s first enduring settlement-Quebec City-at a site not far from Cartier’s abandoned fort.

References:

St Malo: http://www.ville-saint-malo.fr/galeries-dimages/musee-dhistoire-chateau-et-tour-solidor/

Civilization: http://www.civilization.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/colonies-and-empires/founding-sites/

Dieppe Maps: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieppe_maps

Canada: http://www.hellenicaworld.com/Canada/Literature/JGBourinot/en/Canada.html#chap02

Verrazano Letter: http://www.sonofthesouth.net/revolutionary-war/explorers/giovanni-verrazzano.htm

The Portuguese Explorers: http://www.heritage.nf.ca/exploration/portuguese.html

Newfoundland Exploration and Conflict: http://canadachannel.ca/HCO/index.php/4._Newfoundland_Settlement_and_Conflict

John Carter Brown Library: http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/Champlainexhib/Pages/Inventing+.html

Verrazzano World Map: http://cartographic-images.net/347_Verrazano.html

Pierre Desceliers Planosphere: http://cartographic-images.net/378_Pierre_Desceliers.html

Virtual Museum of New France: http://www.civilization.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/introduction/