While we were in the British Museum, we saw this sculpture titled “The Ram in the Thicket” excavated by the archeologist Leonard Woolley. Two almost identical copies of these sculptures were found by Leonard Woolley in the “Great Death Pit” at Ur. The other is now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. It was named the 'Ram in a Thicket' by the excavator Leonard Woolley, who liked biblical allusions. In Genesis 22:13, God ordered Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac, but at the last moment “Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold behind him a ram caught in a thicket by his horns: and Abraham went and took the ram, and offered him up for a burnt offering in the stead of his son”. It depicts a ram (or, more accurately, a Markhor goat) rearing up on his hind legs to eat the leaves on the high branches of a tree (which is also depicted on the shell plaque pictured below). The branches are tipped with buds and eight-pointed rosettes. The statue is made of gold leaf, copper, shell, and lapis lazuli and it's supported on a small rectangular base decorated with a mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. The tube rising from the goat's shoulders was likely used to hold a small tray or offering bowl. The statue is 18 inches high (45.7 centimeters).

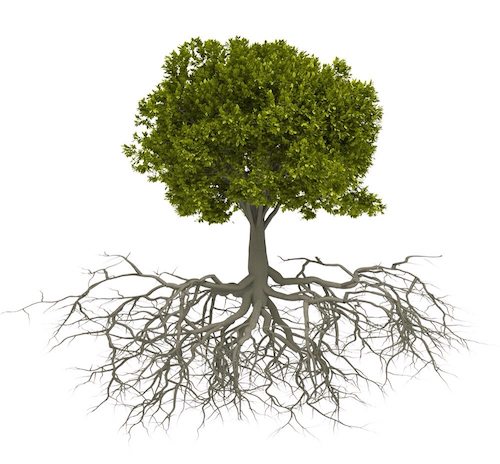

So, aside from these two statues being lovely works of art, they must have had a deep symbolism to the Sumerians since they were buried with a King and were manufactured with such precious materials. I also feel that the passage in Genesis, telling Abraham to substitute the goat for his son Isaac, has greater meaning as well since the goat is a significant enough replacement for his son in God's eyes. Let us begin with the easy part, the gold tree is almost certainly the “Tree of Life/Immortality”, known in many cultures but well known to western readers in the Garden of Eden in the Hebrew Bible. Please note the eight pointed flowers of the tree which corresponds to the Venus symbol Inanna/Ishtar. As I will show in this post, the tree of life is closely associated with Inanna/Ishtar, the Sumerian/Akkadian goddess of love, fertility, and warfare, and goddess of the E-Anna temple at the city of Uruk, her main center. The Markhor goat also has deep significance, possibly associated with Dumzid the Shepherd, Dumzid the Fisherman and King of post-deluvial Uruk, Tammuz (faithful or true son) God of Food and Vegetation and consort of Inanna/Ishtar. I realize this is a fair amount of information to absorb, the rest of the post will explore the tree of life, Dumzid/Tammuz and Inanna/Ishtar in Sumerian/Akkadian/Babylonian mythology.

In this kudurru or boundary stone from southern Babylonia we can see that Inanna/Ishtar is one of the three astral gods of heaven. In her astral aspect, Inana/Išhtar is symbolized by the eight-pointed star of Venus. Thus the symbolism of the eight pointed leaves on the Tree of Life refers directly to Ishtar. I want to point out that the Tree of Life/Immortality is one of two trees in the Garden of Eden, the other being the Tree of Knowlege of Good and Evil from which Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit. Here I am focusing on the Tree of Life because these are grave goods.

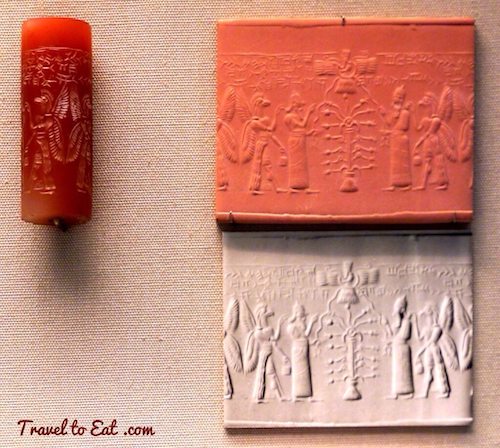

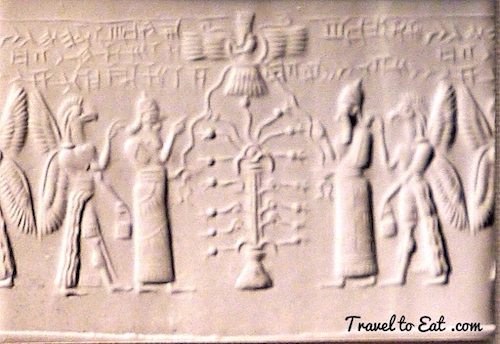

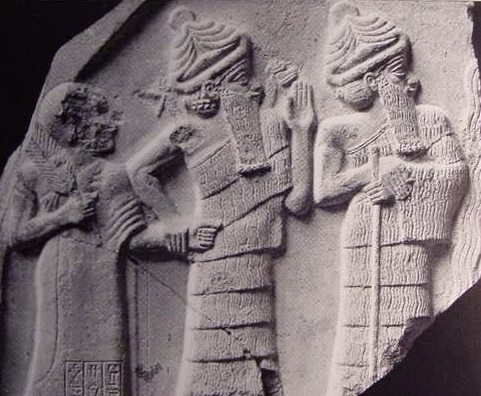

This representation of the “Tree of Life” above shows many of the principle figures of this story. The guards to the entrance of heaven are Dumzid/Tammuz and Gishida/Ningishzida represented above by the winged sphinxes. Ishtar, to the left, and the King Mushezib-Ninurta, to the right, face one another over the “Tree of Life” topped by the winged symbol of the sun. The winged sun or Din.Gur is a symbol associated with divinity, royalty and power in the Ancient Near East (Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Persia).

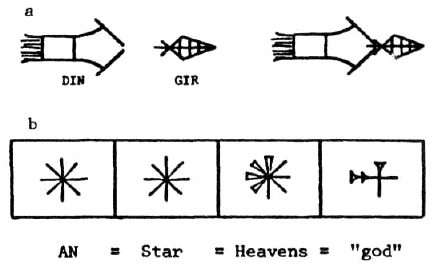

The name Din.Gir is Sumerian meaning “righteous ones of the bright pointed objects”. The Sumerians were referring to the Anunnaki, the pantheon of their gods. They used this two part symbol to designate the Anunnaki collectively.

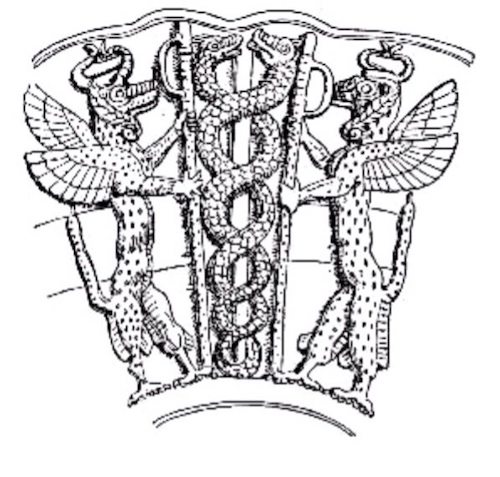

The Libation Vase of Gudea from the Louvre, seen above, shows Gishida/Ningishzida and Dumzid/Tammuz standing on hind-legs holding open stylized door hinges, suggesting their role as a portal guardians. Behind the door we see the staff and coiling snakes which I feel is another representation of the tree of life or the true knowledge of life itself.

Ningishzida is the earliest known symbol of snakes twining (some say copulation) around an axial rod. It predates the Caduceus of Hermes, the Rod of Asclepius and the staff of Moses by more than a millennium. The first thing that should be noted regarding Nin-ĝišzida is that his title is that of 'Nin', a feminine determinative and generally translated as 'Lady', despite this Nin-ĝišzida generally translated as 'Lord of the Good Tree' (which would be 'En'). In trying to figure why this was so Sumerologists draw a blank and simply consider that this was the case with other male Deities. Ningishda is literally translated as “Lord of the Good Tree” in Sumerian but later he became associated with fertility, the underworld, and the healing force of nature. As an animal he walks on four legs, has wings, and two horns.

In human form Ningishzida walks on two legs, has a beard, wears a horned helmet (a symbol that he is a god), and has serpent-dragon heads erupting from his shoulders.

The Underworld aspect of Nin-ĝišzida was serpentine, the roots of the good tree that he represented, the sign for tree root, 'arina', which consists of two crossed signs for serpent (MUŠ), this must be understood as a vast underground network and source of power, as in any forest were all is inter-connected at root level, a natural internet of sorts. However there is a marked difference between the serpentine underworld associations of the roots and those of the firm and upright tree above ground, this as the staff of Moses that when thrown to the ground is as a wriggling serpent, held above ground that of weighty, fair, upright and absolute judgement. The ambiguity of the serpent as a symbol, and the contradictions it is thought to represent, reflect the ambiguity of the use of drugs, which can help or harm, as reflected in the meaning of the term pharmakon, which meant “drug”, “medicine” and “poison” in ancient Greek. Similarly the snake is periodically “reborn” as it sheds it's skin, serving as a symbol of rebirth or immortality.

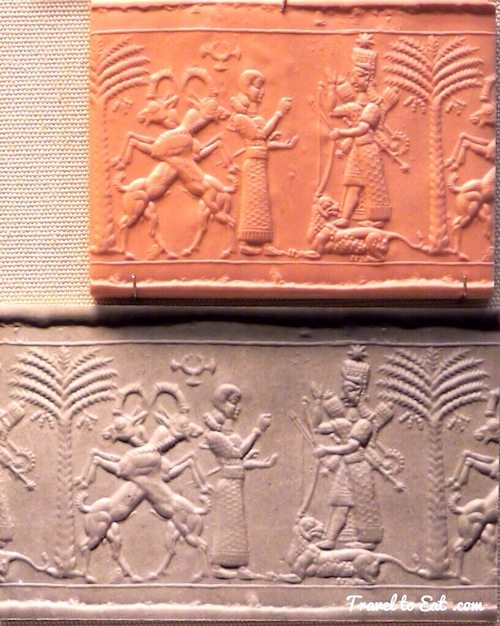

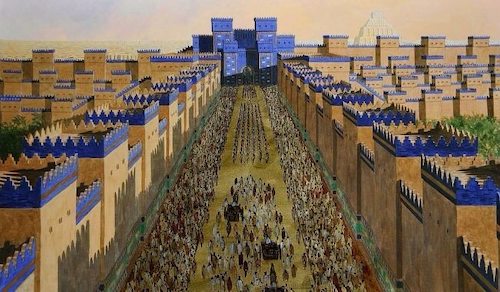

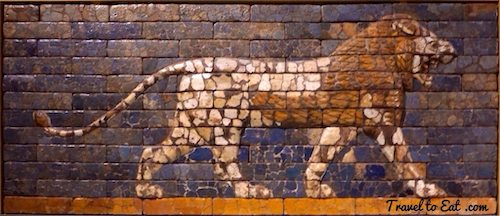

“When the kingship was lowered from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu” so says the Sumerian King List. This is the root of divine rule. Mesopotamian kings displayed their divine inheritance through symbols, the most telling being the branch from the Tree of Life. It all begins with Inanna. There is no doubt of Inanna's connection to the Tree of Life. This may be the origin of the scepter. In the Sumerian tale of Inanna and Enki Inanna travels to Eridu and visits with Enki. During her stay they drink beer together and during this time Enki gives her the mes which in this case includes the throne of kingship and kingship itself. It became tradition that the king be ritually married to Inanna and earn his divine right to rule. Thus we have the trapping of power derived from Inanna in the symbolism of the Tree of Life. In her warrior aspect, Inana/Išhtar is shown dressed in a flounced robe with weapons coming out of her shoulder, often with at least one other weapon in her hand and sometimes with a beard, to emphasize her masculine side. In the cylinder seal above, note the rearing goats to the left, behind the Image of Inanna/Ishtar and the date trees.

In Sumerian mythology, a me is one of the decrees of the gods foundational to those social institutions, religious practices, technologies, behaviors, mores, and human conditions that make civilization, as the Sumerians conceived of it, possible. They are fundamental to the Sumerian understanding of the relationship between humanity and the gods. The mes were originally collected by Enlil and then handed over to the guardianship of Enki who was to broker them out to the various Sumerian centers beginning with his own city of Eridu and continuing with Ur, Meluhha and Dilmun. This is described in the poem, “Enki and the World Order” which also details how he parcels out responsibility for various crafts and natural phenomena to the lesser gods. The Mes were documents or tablets which were blueprints to civilization. They represented everything from abstract notions like Victory and Counsel and Truth to technologies like weaving to writing to social constructs like law, priestly offices, kingship, and even prostitution. They granted power over, or possibly existence to, all the aspects of civilization (both positive and negative). Inanna traveled to Enki's city Eridu, and by getting him drunk, she got him to give her hundreds of Mes, which she took to her city of Uruk. This story may represent the historic transfer of power from Eridu to Uruk.

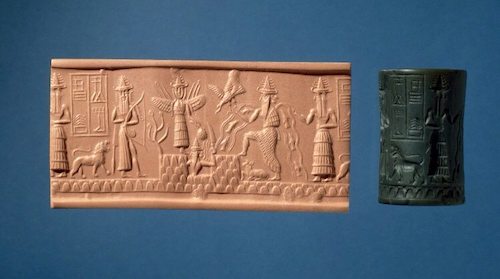

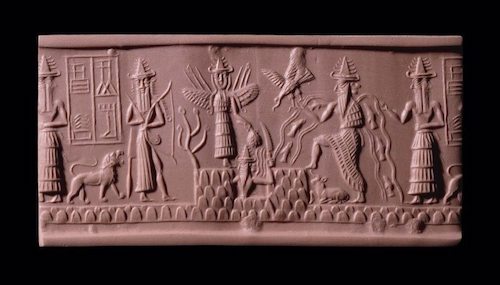

A hunting god (full-face) has a bow and an arrow (?) over his shoulder; a quiver with tassel attached hangs on his back. On the left hand mountain stands a small tree and Ishtar (full-face) who is winged and armed with weapons including an axe and a mace rising from her shoulders. She is holding a bush-like object, probably a bunch of dates, above the sun-god's head. The sun-god Shamash with rays, holding a serrated blade, is just begining to emerge from between two square topped moutains. The water god Ea/Enki stands to the right with one foot placed on the right hand mountain. Behind him stands his two-faced attendant god Usimu with his right hand raised. The writing in the background identifies the seal as belonging to Adda, a scribe.

The markhor is a large species of wild goat that is found today in northeastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, some parts of Azad Kashmir and Indian Kashmir, southern Tajikistan and southern Uzbekistan, although it is an endangered species. The colloquial name is thought by some to be derived from the Persian word mar, meaning snake, and khor, meaning “eater”, which is sometimes interpreted to either represent the species' ability to kill snakes, or as a reference to its corkscrewing horns, which are somewhat reminiscent of coiling snakes. It is my belief that

I would imagine that the common image of goats eating the tender leaves of the Tree of Life is comforting to the living, but even more to the grieving survivors of the dead. The goats and bushes represent life, the abundance of food given to the living and the inherent covenent of everlasting life given by the image. But there is much more. Ningishzida was the ancestor of Gilgamesh, who according to the epic dived to the bottom of the waters to retrieve the plant of life. But while he rested from his labor, a serpent came and ate the plant. The snake became immortal, and Gilgamesh was destined to die. The Tree of Life or World Tree connects the heavens, earth and the underworld.

Although she is called the goddess of love, Inanna is really the goddess of lust. She is not associated with romance, marriage, fertility or child bearing. She is so extreme in her emotions, so psychotic in her desires, and so relentless in getting what she wants, she thus symbolizes the violence of human passion. This is why she is also represents the destruction and carnage of war. Inana/Išhtar is equally fond of making war as she is of making love: “Battle is a feast to her”. The warlike aspect of the goddess tends to be expressed in politically charged contexts in which the goddess is praised in connection with royal power and military might. In the photo above, we see the end panel of the Standard of Ur showing both the Sumerians and the enemy bringing offerings to the Ram in the Thicket. At the bottom we see vulture feeding off the heads of the enemy.

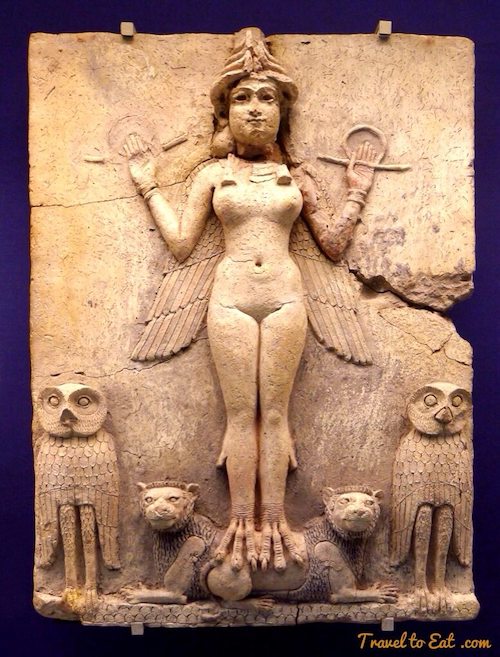

The Burney Relief (also known as the Queen of the Night relief) is a Mesopotamian terracotta plaque in high relief of the Isin-Larsa- or Old-Babylonian period, depicting a winged, nude, goddess figure with bird's talons, flanked by owls, and perched upon supine lions. She wears the horned headdress characteristic of a Mesopotamian deity and holds a rod and ring of justice, symbols of her divinity. She represents either Inanna/Ishtar or her sister Her long multi-coloured wings hang downwards, indicating that she is a goddess of the Underworld. She represents Inanna/Ishtar or Ereshkigal, Queen of the underworld. Her legs end in the talons of a bird of prey, similar to those of the two owls that flank her. The owls represent the knowledge of the MES,mor the tree of knowledge. The background was originally painted black, suggesting that she was associated with the night. She stands on the backs of two lions, and a scale pattern indicates mountains. The relief is displayed in the British Museum in London, which has dated it between 1800 and 1750 BCE. It originates from southern Iraq, but the exact find-site is unknown. Apart from its distinctive iconography, the piece is noted for its high relief and relatively large size, which suggests that is was used as a cult relief, which makes it a very rare survival from the period. She was originally painted red with multicolored wings.

One of the most famous myths about Ishtar describes her descent to the underworld. In this myth, Ishtar approaches the gates of the underworld and demands that the gatekeeper open them:

- If thou openest not the gate to let me enter,

- I will break the door, I will wrench the lock,

- I will smash the door-posts, I will force the doors.

- I will bring up the dead to eat the living.

- And the dead will outnumber the living.

The gatekeeper hurried to tell Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Underworld and the sister of Inanna/Ishtar. Ereshkigal told the gatekeeper to let Ishtar enter, but “according to the ancient decree”. The gatekeeper lets Ishtar into the underworld, opening one gate at a time. At each gate, Ishtar has to shed one article of clothing. When she finally passes the seventh gate, she is naked. In rage, Ishtar throws herself at Ereshkigal, but Ereshkigal orders her servant Namtar to imprison Ishtar and unleash sixty diseases against her.

Formerly, scholars believed that the myth of Ishtar's descent took place after the death of Ishtar's lover, Tammuz: they thought Ishtar had gone to the underworld to rescue Tammuz. However, the discovery of a corresponding myth about Inanna, the Sumerian counterpart of Ishtar, has thrown some light on the myth of Ishtar's descent, including its somewhat enigmatic ending lines. According to the Inanna myth, Inanna can only return from the underworld if she sends someone back in her place. Demons go with her to make sure she sends someone back. However, each time Inanna runs into someone, she finds him to be a friend and lets him go free. When she finally reaches her home, she finds her husband Dumuzi (Babylonian Tammuz) seated on his throne, not mourning her at all. In anger, Inanna has the demons take Dumuzi back to the underworld as her replacement. Dumuzi's sister Geshtinanna is grief-stricken and volunteers to spend half the year in the underworld, during which time Dumuzi can go free. Finally, Inanna relents and changes her decree thereby restoring her husband Dumuzi to life; an arrangement is made by which Geshtinana will take Dumuzid's place in Kur for six months of the year: “You (Dumuzi), half the year. Your sister (Geštinanna), half the year!”

Inanna/Ishtar was often was decorated with rich jewelry, like the examples shown above. The unknown god shown above shares the same sacred hat and red and black colors as Ishtar.

Inanna rescued the huluppu tree at the time of beginnings, “when what was needful had first come forth.” Is it possible that the huluppu tree was among the “needful”? Perhaps the huluppu was the World Tree, which connects heaven, earth, and underworld. In other mythologies, the World Tree usually has a serpent in its roots and often a bird in its branches. When Gilgamesh, the descendant of Ningishzida, had disposed of the huluppu tree's inhabitants, he uprooted it, thus eliminating, finally, any natural connection between earth and underworld. He then gave the wood to Inanna to make into a bed and a throne, the furniture used in the “Sacred Marriage.” However, the furniture, which was essentially constructed from her body, was no longer entirely hers. The institution of kingship had appropriated it and, with the furniture, Inanna herself. What is more, the poem presents her as willingly co-operating in her own demotion. Both she and the furniture would henceforth serve a male monarchy in a male-dominated society. In this way, society was able to circumscribe her and direct her undoubted power into channels that would be useful to the male-dominated city.

Easter is a pagan and ancient celebration of spring, of death and rebirth. It is a recognition of creative power manifesting as the old is fully released. The cycle of death and rebirth is a constant metaphor in spirituality. We must let old beliefs and issues die for new realities to manifest. Many religions celebrate the Spring Equinox including Judaism (Passover), Christianity (Easter), the Festival of Isis (Egypt), Feast of Cybele (Ancient Rome) and many others. Despite internet reports to the contrary, Easter is not associated with Ishtar. The word Easter does not appear to be derived from Ishtar, but from the German Eostre, the goddess of the dawn—a bringer of light. English and German are in the minority of languages that use a form of the word Easter to mark the holiday. Elsewhere, the observance is framed in Latin pascha, which in turn is derived from the Hebrew pesach, meaning of or associated with Passover. Ishtar and Easter appear to be homophones: they may be pronounced similarly, but have different meanings. Interestingly, the dead Tammuz was widely mourned in the Ancient Near East at Summer Solstice when the heat killed plants and Tammuz returned to the underworld. These mourning ceremonies were observed even at the very door of the Temple in Jerusalem in a vision the Israelite prophet Ezekiel was given, which serves as a Biblical prophecy which expresses YHWH's message at His people's apostate worship of idols:

Then he brought me to the door of the gate of the Lord's house which was toward the north; and, behold, there sat women weeping for Tammuz. Then said he unto to me, 'Hast thou seen this, O son of man? turn thee yet again, and thou shalt see greater abominations than these. —Ezekiel 8:14-15

In the end of this long post, I have no more idea of the meaning of the Ram in the Thicket than when I first began. The story of Adam and Eve comes to mind, substituting Inanna/Ishtar for Eve and Tammuz/Dumzid for Adam facilitated by the Anunnaki, pantheon of the Sumerian Gods. I have chosen works from Canova to illustrate the healing power of love, Venus and Adonis and Cupid and Psyche. It is a little spooky how Cupid mimics the appearance of Tammuz/Damzid. Even though Inanna/Ishtar began as a harlot, seducing Adam from his animal companions, at the end of the day Tammuz/Dumzid remained the love of her life. The tender scene of a simple goat eating at the Tree of Life would be a perfect gift to Ishtar, Goddess of Heaven and lover of Tammuz, easing the way into the afterlife. After all, in life or death, what more do we want than the love and rembrance from those closest to us?

References:

Tree of Life: http://firstlegend.info/thetreeoflife.html

Ishtar's Descent to the Nether World: http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/sum/sum08.htm#page_83

Inanna/Ishtar: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/inanaitar/

Genesis' Genesis: http://prophetess.lstc.edu/~rklein/Documents/genesisgenesis.htm

The Myth of Adapa: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/216/

Inana's Descent to the Nether World: http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm

Sumerian Double Helix God: http://ferrebeekeeper.wordpress.com/2012/06/26/

Ningishzida: http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread999988/pg1

Balbale to Ningishzida: http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section4/tr4191.htm

Serpents in Sumeria: http://www.bibleorigins.net/Serpentningishzida.html

Mesopotamian Pantheon: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/221/

Myth of the Huluppu Tree: http://www.piney.com/BabHulTree.html

Inanna and the Huluppu Tree: http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM05/spotlight.htm

Sacred Marriage: http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/essays/fertilitysacremarriage.html

Easter: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/2013/03/31/beyond-ishtar-the-tradition-of-eggs-at-easter/