The Topkapi Palace is the biggest and one of the most popular sites to visit in Istanbul. It was built in between 1466 and 1478 by the sultan Mehmet II on top of a hill in a small peninsula, dominating the Golden Horn to the north, the Sea of Marmara to the south, and the Bosphorus strait to the north east, with great views of the Asian side as well. The palace was the political center of the Ottoman Empire between the 15th and 19th centuries, until they built Dolmabahce Palace by the waterside. The palace was opened to the public as a museum in 1924 by the order of Ataturk. The Istanbul Archaeology Museum consists of three museums: the Archaeological Museum, the Museum of the Ancient Orient and the Tiled Pavilion Museum or Museum of Islamic Art. The three museums house over one million objects that represent almost all the eras and civilisations in world history. As part of the core collection, on the second floor, they have spectacular collection of Greco-Roman sculpture from the 6th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. Since almost all the important eras of sculpture in this time period were on display, I have compiled a history of Greek and Roman Sculpture.

The Bronze Age Collapse

The Bronze Age Mycenaean Greek culture (1600–1100 BCE) has not yielded sculptures of any great size. The statues of the period consists for the most part of small terracotta figurines (usually female) found at almost every Mycenaean site in mainland Greece, in tombs, in settlement debris, and occasionally in cult contexts. Mycenaean Greece perished with the collapse of virtually all Bronze Age cultures in the eastern Mediterranean (1200–1050 BCE), to be followed by the so-called Greek Dark Ages (1200–800 BCE), a recordless transitional period leading to Archaic Greece. Significant shifts occurred from palace-centralized to city-centralized forms of government, significant population decreases, and the extensive use of iron instead of bronze. The decoration on Greek pottery after about 1100 BC lacks the elegant figures decorating Mycenaean pottery and is restricted to simpler, generally geometric styles (1000–700 BCE). By the 8th century BCE, a new alphabet system was adopted from the Phoenicians by a Greek with first-hand experience of it. The Greeks adapted the abjad used to write Phoenician, notably introducing characters for vowel sounds and thereby creating the first truly alphabetic writing system. The new alphabet quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean and was used to write not only the Greek language, but also Phrygian and other languages in the eastern Mediterranean.

Following upheavals in mainland Greece during the Bronze Age Collapse, the Aegean coast of Asia Minor was heavily settled by Ionian and Aeolian Greeks, usurping the related but earlier Mycenaean Greeks, and became known as Ionia and Aeolia. The Greek Dark Ages were a time of Ionian migration, settlement and consolidation in an alliance called the Ionian League on the west coast of Anatolia. The Archaic Period of Greece began with a sudden and brilliant flash of art and philosophy on the coast of Anatolia. In the 6th century BC, Miletus was the site of origin of the Greek philosophical (and scientific) tradition, when Thales, followed by Anaximander and Anaximenes (known collectively, to modern scholars, as the Milesian School) began to speculate about the material constitution of the world, and to propose speculative naturalistic (as opposed to traditional, supernatural) explanations for various natural phenomena.

Anatolia Under the Persians (546–333 BCE)

In 546 BCE the Achaemenid Persians captured Sardis, the capital of the Lydian Kingdom and a city which they had long coveted. Thereafter, Anatolia remained under the control of the Persians for 200 years. The political changes which occurred during this period also influenced the culture and art created within this East-West meeting-ground. At the newly established seats of the Persian satraps (provincial governors), such as Dascyleium (Ergili near Lake Manyas), Sardis (in the vicinity of Manisa) and Halicarnassus (Bodrum), objects of art were produced both under Anatolian and under Persian influence. Stelae and reliefs discovered at the Dascyleium excavations reveal the characteristics of this new style, which is a synthesis of eastern and western cultural traditions meeting for the first time.

Reliefs

The term relief is from the Latin verb relevo, to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the sculpted material has been raised above the background plane. What is actually performed when a relief is cut in from a flat surface of stone (relief sculpture) or wood (relief carving) is a lowering of the field, leaving the unsculpted parts seemingly raised. The technique involves considerable chiselling away of the background, which is a time-consuming exercise. Despite the difficulties, relief was used over 12,000 years ago to decorate the temples at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, most ancient Egyptian temples had their walls decorated with hieroglyphs in relief and both the Hittites and Persians had a history of reliefs on outdoor stone walls, temples and gravestones. Most ancient architectural reliefs and statues were originally painted, which helped to define forms. Interestingly, neither the Greeks or the later the Romans had much interest in decorating walls with reliefs, preferring to simply paint them.

This relief documents the Ionian-Persian style of Anatolia, in which the dominant royal Persian art demonstrably adopted a great deal from the Ionian style of Anatolia. For example, Cybele, the native mother goddess of Anatolia, is shown as winged and wearing a high cap. The cart with its many-spoked wheels, the horses with their tails bound tightly in the middle, the crown worn by the seated woman and the high boots worn by men, all are features of Persian art, while the form of the stele, the tripod and the vessel on top and the wife and her husband intimately sitting together are typical of Greek art.

Here we have a dynamic and beautiful depiction of a Persian racing chariot drawn by two horses. The horses’ mane and tail are plaited, and there are tassels around their neck within the harness. The chariot has 8-spoked wheels and the carriage is decorated with a lion’s relief, both typical of Persian chariots. The standing man’s hair is long and is held together with a ribbon, which falls on his shoulder. The charioteer’s right hand holds a whip while his left hand grasps the horses’ reins. Compare the this relief to an impression from the cylinder seal of Darius the Great. The seal impression has the size of the horses too small, the figures are stick-like and the overall impression of the scene is almost a still-life. In our relief the scene comes to life with well proportioned horses accented by the opposite horse rearing it’s head, natural pose of the charioteer looking straight ahead and the well proportioned arms holding whip and reins. Thus the realism of Classical Greek artistry animates a typical Persian scene. According to Greek historians, the Achaemenid armies had large numbers of chariots that could have their wheel hubs fitted with scythe blades to mow down infantry in a frontal assault. Initially terrifying, no doubt, in the long run, especially against Alexander, these chariots proved useless in the face of disciplined troops and far more mobile cavalry. In post-Achaemenid Iran chariots fell into total obsolescence as vehicles of war. Cyzicus the ancient city had been founded by the settlers from Miletus and was one of the oldest Ionian colonies on the coast of the Sea of Marmara.

Archaic Kouros and Kore

Archaic Greek sculptors were at work in marble on the islands of Naxos, Paros, and Samos before the end of the seventh century BCE, and, before long, evidence of their work appears on the mainland, too. The two major types of sculpture in the round prevalent in the sixth century BC were the standing nude male, the kouros (plural, kouroi) and the standing clothed female, the kore. The kouroi stood in sanctuaries or cemeteries, occasionally as representations of divinities (at one time they were all thought to be images of Apollo), but most often as votive offerings to the gods, or as commemorative markers over graves. Towering, vibrant statues, they stood with one leg advanced and arms by their sides, held straight or slightly bent with fists clenched. Carved in from four sides, the statue retained the general shape of the marble block from which they were sculpted. Archaic Greek sculptors reduced human anatomy and musculature in these statues to decorative patterning on the surface of the marble.

A direct influence between Egyptian sculptures (in particular the figure of Horus) and the kouros type has long been conjectured, not least because of trade and cultural relations that are known to have existed since the mid-seventh century BCE. A 1978 study by Eleanor Guralnick found the correlation between the Second Canon of the 26th Egyptian Dynasty and Greek kouroi to be widely distributed but not universal. The system of proportion in the second Egyptian canon of the Saite period consisted of a grid of twenty-one and one fourth parts, with twenty-one squares from the soles of the feet to a line drawn through the centres of the eyes. The grid was applied to the surface of the block being carved, allowing the major anatomical features to be located at fixed grid points. Thus the act of carving the figure was greatly simplified.

Severe Archaic Greek Relief

The “Severe” style of sculpture marks the transition from the Archaic to the early Classical period. This style shows a vested interest in naturalism, which was a more subdued and realistic departure from the Archaic. Subjects were now on the verge of emotional expression and poses that imply motion. The Severe style is a product of much experimentation. The “Archaic smile” and plank-like poses of Kouros were replaced by sculpture that displayed sharp facial features and possessed staring eyes. Clothed sculptures now donned simplified drapery, marking a return to the plainer “Doric” garments. Bodily forms were significantly more defined as anatomical details were attended to by the artists of this period. The contrapposto pose, involving one leg held back and supporting the body with the other leg free, allows the upper torso to swing off the body’s axis and thus lends a more realistic feeling to the piece. While the the piece looks very formal, there is much more fluidity of the figures and they are actually doing things. Funeral statuary evolved during this period from the rigid and impersonal kouros of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical period.

Herma

A “Herma” is a sculpture with a head, and perhaps a torso, above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height (as seen above). Hermae were so called either because the head of Hermes was most common or from their etymological connection with the Greek word ἕρματα (blocks of stone), which originally had no reference to Hermes at all. The form originated in Ancient Greece, and was adopted by the Romans. In many parts of Greece there were piles of stones by the sides of roads, especially at their crossings, and on the boundaries of lands. The religious respect paid to such heaps of stones, especially at the meeting of roads, is shown by the custom of each passer-by throwing a stone on to the heap or anointing it with oil. Later there was the addition of a head and phallus to the column, which became quadrangular (the number 4 was sacred to Hermes). The statues were thought to ward off harm or evil and were placed at crossings, country borders and boundaries as protection. Before his role as protector of merchants and travelers, Hermes was a phallic god, associated with fertility, luck, roads and borders. In Athens, where the hermai were most numerous and most venerated, they were placed outside houses as talismans for good luck. They would be rubbed or anointed with olive oil and adorned with garlands or wreaths.

Classical Athena

Athena, also referred to as Athene, is a very important goddess of many things. She is goddess of wisdom, courage, inspiration, civilization, law and justice, strategic warfare, mathematics, strength, strategy, the arts, crafts, and skill. She is known most specifically for her strategic skill in warfare and is often portrayed as companion of heroes and is the patron goddess of heroic endeavour. Athena was born from Zeus after he experienced an enormous headache and she sprang fully grown and in armour from his forehead. Drapery of the classical and Hellenistic periods of Greek art sometimes appears purely as a foil for nudity, clinging and spiraling around the body. Often, this effect occurs in response to compositional requirements rather than to any natural phenomenon or dressing practice. It was socially accepted that textile making was primarily women’s responsibility, and the production of high quality textiles was regarded as an accomplishment for women of high status. The most expensive textile was finely woven linen and very soft wool. The linen was almost transparent, as the Greeks had no problem showing off their body. Athena is wearing a ”Peplos”, consisting of a large rectangular piece of material folded vertically and hung from the shoulders, with a broad overfold. During the early periods, it was belted around the waist, usually beneath the overfold; if the overfold was long, however, the belt was sometimes placed on top of it, as seen in many statues of Athena. Also note the contrapposto pose, with the weight on one leg and the extension of the peplos to the ankle, as would be proper for a Greek woman.

Classical Artemis

Although the high point of Classical expression was short-lived (480–323 BCE), it is important to note that it was forged during the Persian Wars (490–479 BCE) and continued after the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) between Athens and a league of allied city-states led by Sparta. The conflict continued intermittently for nearly thirty years. Athens suffered irreparable damage during the war and a devastating plague that lasted over four years. Although the city lost its primacy, its artistic importance continued unabated during the fourth century BCE. The elegant, calligraphic style of late fifth-century sculpture was followed by a sober grandeur in both freestanding statues and many grave monuments. Artemis is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, the Moon, and chastity. She is the daughter of Zeus and Leto, and the twin sister of Apollo. She was the patron and protector of young girls, and was believed to bring disease upon women and relieve them of it. Artemis was worshipped as one of the primary goddesses of childbirth and midwifery along with Eileithyia. Her best known cults were on the island of Delos (her birthplace), in Attica at Brauron and Mounikhia (near Piraeus), and in Sparta. The ancient Spartans used to sacrifice to her as one of their patron goddesses before starting a new military campaign. Here she is dressed in a short knee-length hunting tunic with what appears to be a cloak around her waist. This sculpture has taken contrapposto pose to a new level with an arm resting on a support. There is the subtle sense that she is shown as a more masculine type of woman here with a sturdy body, short tunic and high sandals seen typically in depictions of men.

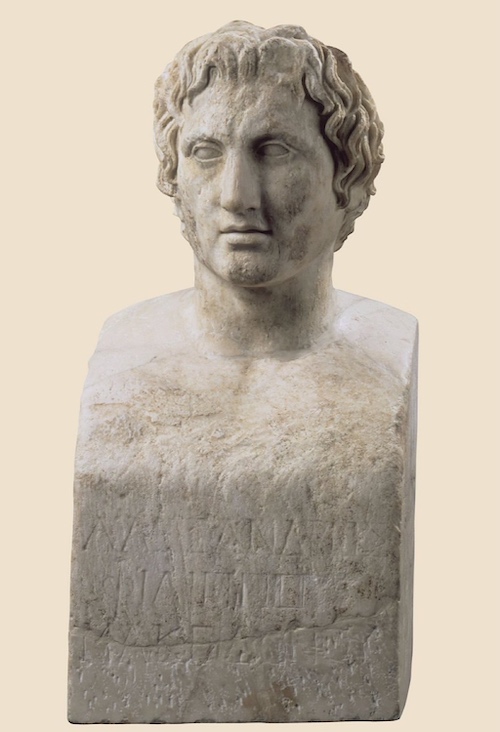

Alexander the Great

Within eleven years, Alexander the Great subdued the Persian empire of western Asia and Egypt, continuing into Central Asia as far as the Indus River Valley. During his reign, Alexander cultivated the arts as no patron had done before him. Among his retinue of artists was the court sculptor Lysippos, arguably one of the most important artists of the fourth century BCE. His works, most notably his portraits of Alexander (and the work they influenced), inaugurated many features of Hellenistic sculpture, such as the heroic ruler portrait. When Alexander died in 323 BCE, his successors, many of whom adopted this portrait type, divided up the vast empire into smaller kingdoms that transformed the political and cultural world during the Hellenistic Period (323–31 BCE). No direct trace of Lysippos’s work has come down to us. Most antique bronze statues disappeared long ago, and are known only through small bronze copies or Roman versions in marble. The majority of ancient depictions of Alexander the Great show a rather effeminate-looking youth. However there is another portrait which is said to be a Roman copy of a bronze made by Lysippus, Alexander’s personal sculptor, at the Louvre (seen above). This bust was part of a gallery of herms featuring portraits of famous men, unearthed in 1779 during an excavation at Tivoli organized by Joseph Nicolas Azara, the Spanish ambassador to the Holy See and, later, to France.

Helenistic Sculpture

Hellenistic Culture is a term for Greek culture during the Hellenistic age, which begun after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, and ended in 146 BCE when the Roman Republic conquered most of mainland Greece. Alexander’s brief but thorough empire-building campaign changed the world, it spread Greek ideas and culture from the Eastern Mediterranean to Asia. Hellenistic kings became prominent patrons of the arts, commissioning public works of architecture and sculpture, as well as private luxury items that demonstrated their wealth and taste. Within this thriving, expansive network new centers of “Greek” art sprung up, questioning the previous dominance of Athens as the cultural epicenter of the ancient world. Now, cities like Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamon began making a name for themselves in the artistic arena. They took the classical ways, but then added local flare or improved technical abilities. During this period sculpture became more naturalistic, and also expressive; there is an interest in depicting extremes of emotion. On top of anatomical realism, the Hellenistic artist seeks to represent the character of his subject, including themes such as suffering, sleep or old age. The tall, proud statues found in high classical art were punched, twisted and tortured. They distorted the beautifully sculpted youths of Athens’ golden age into decrepit or dying individuals. Here, the flutist Marsyas was flayed alive in a cave near Celaenae for his hubris in challenging Apollo to a musical contest.

One of the immediate results of the new international Hellenistic culture was the widened range of subject matter that had little precedent in earlier Greek art. There are representations of unorthodox subjects, such as Hermaphroditus. The artists picked up the old perfect bodies, wrapped gracefully and modestly in sculptured cloths and threw them into the water till they were drenched. The women became erotic, with shapely figures bravely carved through flimsy fabric or simply naked. They perfected transparency portrayed in stone. In Greek mythology, Hermaphroditus was the son of Aphrodite and Hermes. According to Ovid, he was born a remarkably handsome boy with whom the naiad Salmacis fell in love and prayed to be united forever. A god, in answer to her prayer, merged their two forms into one and transformed them into an androgynous form. His name is compounded of his parents’ names, Hermes and Aphrodite. Hermaphroditus’s association with marriage seems to have been that, by embodying both masculine and feminine qualities, he/she symbolized the coming together of men and women in sacred union.

Another expansion of the Classical oeuvre in the Hellenistic culture was in the depiction of children and young adults. Here we have an elegant depiction of a young athlete in his cloak or himation. A growing number of art collectors commissioned original works of art and copies of earlier Greek statues. Likewise, increasingly affluent consumers were eager to enhance their private homes and gardens with luxury goods, such as fine bronze statuettes, intricately carved furniture decorated with bronze fittings, stone sculpture, and elaborate pottery with mold-made decoration. These lavish items were manufactured on a grand scale as never before. The most avid collectors of Greek art, however, were the Romans, who decorated their town houses and country villas with Greek sculptures according to their interests and taste. By the first century BCE, Rome was a center of Hellenistic art production, and numerous Greek artists came there to work. This would have been an elegant and artistic addition to any upwardly aspiring Roman household.

Archaistic Sculpture

From at least the fifth century BCE on, Greek artists deliberately represented certain works of art in the style of previous generations in order to differentiate them from other works in contemporary style. Archaistic, the most common retrospective style in Greek and Roman sculpture, refers to works of art that date after 480 BCE but share stylistic affinities with works of the Greek Archaic period (700–480 BCE). Archaistic figures stand with legs unbent and occasionally with one leg forward. The shoulders and hips are level, and the head faces directly forward. In general, the most often imitated costumes are the late Archaic chiton combined with a diagonal himation. This statue in the form of a Caryatid in the Archaistic Style shows a standing woman. The right arm hangs by her side and holds her himation. The left arm is raised (the distal part is now lost) as if she intends to carry the load of a stone architrave (which would have been placed on her cylindrical headdress or polos). The details of the chiton and her hair were exquisitely carved. The himation, or mantle, was a smaller oblong of cloth, buttoned along one long side, in such a way that it could be worn over the right shoulder and under the left arm. This was most often worn on top of the chiton. The chiton, often of linen, was like the peplos, a rectangle of cloth. It was buttoned along the upper edge in two sections to allow holes for head and arms and was sleeved and belted. While this sculpture clearly looks like a Caryatid to be used in a building, it also may have been commissioned as an independent piece of art.

Roman Imperial Portraits

With the establishment of the principate system under Augustus, the imperial family and its circle soon came to monopolize official public statuary. The Principate is characterised by the reign of a single emperor (princeps) and an effort on the part of the early emperors, at least, to preserve the illusion of the formal continuance, in some aspects, of the Roman Republic. Official imperial portrait types were principally displayed in sebasteia, or temples of the imperial cult, and were carefully designed to project specific ideas about the emperor, his family, and his authority. These sculptures were extremely useful as propaganda tools intended to support the legitimacy of the emperor’s powers. Two of the most influential, and most widely disseminated, media for imperial portraits were coins and sculpture, and official types laden with propagandistic connotation were dispersed throughout the empire to announce and identify the imperial authority. Scholars believe that official portrait types were created in the capital city of Rome itself and distributed to the provinces to serve as prototypes for local workshops, which could adapt them to conform to local iconographic traditions and therefore have more meaningful local appeal.

Agrippina The Elder was a prominent member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the wife of Germanicus. At the time of her birth, her brothers Lucius and Gaius were the adoptive sons of Augustus and were his heirs until their deaths in AD 2 and 4, respectively. Following their deaths, her cousin Germanicus was made the adoptive son of Tiberius as part of Augustus’ succession scheme in the adoptions of AD 4 in which Tiberius was adopted by Augustus. As a corollary to the adoption, Agrippina was wed to Germanicus in order to bring him closer to the Julian family. On her mother’s side, she was the younger granddaughter of Augustus. She was the Stepdaughter of Tiberius by her mother’s marriage to him, and sister in law of Claudius, the brother of her husband Germanicus. Her son Gaius, better known as “Caligula”, would be the fourth emperor, and her grandson Nero would be the last emperor of the dynasty. All very confusing but I must say this bust is a particularly nice representation of Agrippina as a young woman. You can see it has been broken, perhaps related to her exile to the island of Pandateria due to court intrigue in 29 CE by Tiberius, where she would remain until her death by starvation in 33 CE.

Roman Patrician Sculpture

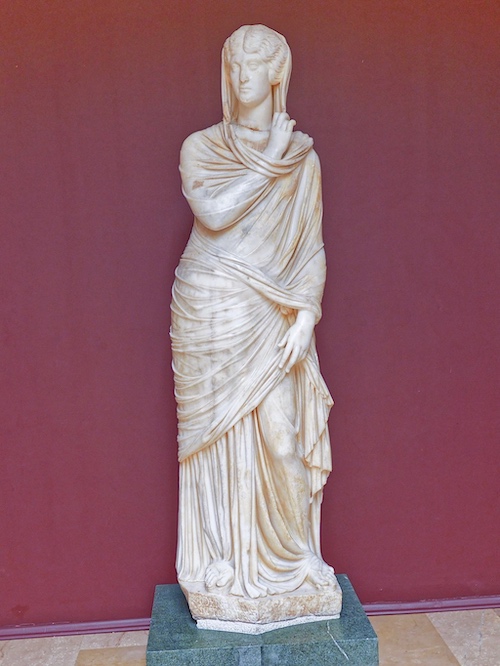

Pisidia was a region of ancient Asia Minor located north of Lycia, bordering Caria, Lydia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, and corresponding roughly to the modern-day province of Antalya in Turkey. Among Pisidia’s settlements were Antioch(ad/in Pisidia) not to be confused with Antioch, the ancient capital of Syria. During the Roman period Pisidia was colonized with veterans of its legions to maintain control. For the colonists, who came from poorer parts of Italy, agriculture must have been the area’s main attraction. Under Augustus, eight such colonies were established in Pisidia. The years of the Antonine dynasty are often considered the golden age of the Roman Empire. Except for the northern wars of Marcus Aurelius, the frontiers were stable, there was prosperity at home, the succession was uncontested and the arts flourished. Antonine rule commenced with the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161 CE) and included those of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE), Lucius Verus (161–169 CE), and Commodus (177–192 CE). Obviously there was some wealth in the area judging by this elegant statue of a private woman. It is done in the classical Greek style, as the woman wears a long and voluminous chiton with a large himation, covering the entire body and falling down onto the plinth. Although the body of the sculpture is classic, it follows the Roman tradition of personalizing the face.

Aphrodisias was the metropolis (provincial capital) of the region and Roman province of Caria in southwestern Turkey, in the upper valley of the Morsynus River. White and blue grey Carian marble was extensively quarried from adjacent slopes in the Hellenistic and Roman periods, for building facades and sculptures. Marble sculptures and sculptors from Aphrodisias became famous in the Roman world. Many examples of statuary have been unearthed in Aphrodisias, and some representations of the Aphrodite of Aphrodisias also survive from other parts of the Roman world, as far afield as Pax Julia in Lusitania. The city had notable schools for sculpture, as well as philosophy, remaining a center of paganism until the end of the 5th century. Eve D’Ambra has a wonderful analysis of this type of sculpture, ”Female portrait statues usually consisted of conventional draped bodies and individualized heads, the latter adorned with highly styled hair in the late first and second centuries CE. The hairstyles that dominate the portraits suggest an urbane sophistication that was at odds with moralists’ vitriolic attacks on feminine vanity and the vices accompanying it. Material culture, however, tells a different story with the piles of perfume vials scattered across archaeological sites and marble busts depicting hardened dowagers under clouds of curls and jeweled headdresses. Clearly beauty and refinement were sought after by respectable, upstanding women.” Note the shoes rather than sandals, a mark of her wealth and unusual in this style of sculpture.

Since most ancient bronze statues have been lost or were melted down to reuse the valuable metal, Roman copies in marble and bronze often provide our primary visual evidence of masterpieces by famous Greek sculptors. This elegant portrait of Sappho comes as a bust, a form perfected by the Romans. As one of the principal cities of Roman Asia, Smyrna vied with Ephesus and Pergamum for the title “First City of Asia. Sappho (630–570 BCE) is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by a lyre, originally from the island of Lesbo. In ancient times, Sappho was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets and was given names such as the “Tenth Muse” and “The Poetess”. Beyond her poetry, she is well known as a symbol of love and desire between women, with the english words sapphic and lesbian being derived from her own name and the name of her home island respectively. While Sappho’s poetry was admired in the ancient world, her character was not always so well considered. In the Roman period, critics found her lustful and perhaps even homosexual, not a problem for Greek culture but a taboo for the Romans. No reliable portrait of Sappho’s physical appearance has survived; all extant representations, ancient and modern, are artists’ conceptions. In the Tithonus poem she describes her hair as now white but formerly melaina (black). A literary papyrus of the second century CE describes her as pantelos mikra, quite tiny.

According to Homer, Oceanus was the ocean-stream at the margin of the (assumed flat) habitable world, the father of everything, limiting it from the underworld and flowing around the Elysium. The most famous statue of Oceanus is at the Trevi fountain in Rome. This particular depiction reminds me of a different source of artistic inspiration, the Etruscans. Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighbouring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on top of a sarcophagus lid propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period, just as Oceanus is posed above. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, at first in Southern Italy and then the entire Hellenistic world except for the Parthian far east, official and patrician sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, from which specifically Roman elements are hard to disentangle, especially as so much Greek sculpture survives only in copies of the Roman period. By the 2nd century BCE, most of the sculptors working at Rome were Greek, often enslaved in conquests such as that of Corinth (146 BCE), and sculptors continued to be mostly Greeks, often slaves, whose names are very rarely recorded.

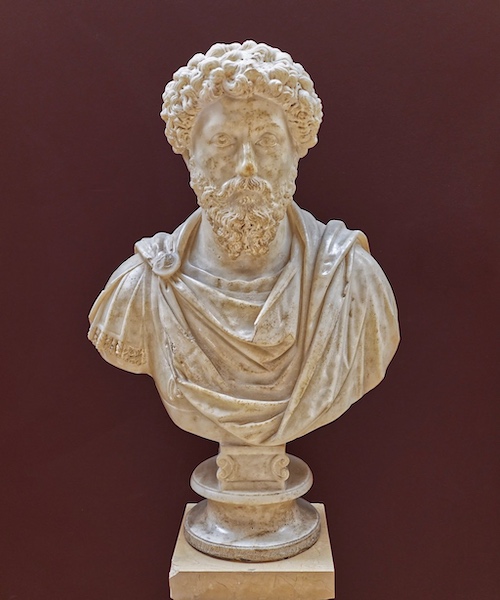

Marcus Aurelius

I am going to end with this marvelous bust of Marcus Aurelius (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus) who was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 CE and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers traditionally known as the Five Good Emperors, and the last emperor of the Pax Romana or Roman Peace. This peaceful period is traditionally dated as commencing from the accession of Caesar Augustus, founder of the Roman principate, in 27 BC and concluding in 180 AD with the death of Marcus Aurelius. Since it was inaugurated by Augustus with the end of the Final War of the Roman Republic, it is sometimes called the Pax Augusta. During this period of approximately 207 years, the Roman Empire achieved its greatest territorial extent and its population reached a maximum of up to 70 million people – a third of the world’s population at the time. Continued development in Roman portrait styles was spurred by Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus, whose portraits feature new levels of psychological expression that reflect changes not only in the emperors’ physical state but their mental condition as well. There are approximately 110 known portraits of Marcus Aurelius and these have been grouped into four typological groupings. The first two types belong to the emperor’s youth, before he assumed the duties of the principate. For what it is worth, this is a type 4 official portrait, created between 170 and 180 CE, which shows the emperor slightly more advanced in age with a very full beard that is divided in the center at the chin, showing parallel locks of hair.

Students from the Bayerische Theaterakademie August Everding created portraits in silicone of Roman emperors and famous Roman women based on their marble portraits and on historical research. These silicone portraits could be seen together with their Roman originals in the Glyptothek in Munich and you can watch the process on the included YouTube video. Obviously, no one can perfectly recreate a face from the past but this portrayal of Marcus Aurelius certainly has the humanity of a philosopher.

As always I hope you enjoyed the post, if you are in Istanbul you should certainly visit the Istanbul Archaeology Museum at the Topkapi Palace to see this sumptuous collection of Greco-Roman sculpture in person.

References:

Hittites. Boğazköy Museum, Turkey

Babylonian World Map, British Museum, London

The Art of Classical Greece (480–323 BCE)

Retrospective Styles in Greek and Roman Sculpture

The Lysippus bust of Alexander the Great

Aphrodisias : The Lost City of Sculptures

D’Ambra, E. (2014). Beauty and the Roman female portrait. In J. Elsner & M. Meyer (Eds.), Art and Rhetoric in Roman Culture (pp. 155–180). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511732317.007