The history museum tells the story of Saint-Malo and its famous residents. It is located in the keep and tower of Saint-Malo’s castle. Back in 1838, the town of Saint-Malo decided to create a collection of portraits of prominent townspeople, to include Jacques Cartier, Duguay-Trouin, Mahé de La Bourdonnais, Maupertuis (famous mathematician), Chateaubriand, Surcouf, and Lamennais (priest and philosopher). The original 19th century museum was destroyed in 1944 during the struggle to liberate the town, and the present collection, numbering over 8,500 items, is themed around the maritime history of Saint-Malo and the surrounding area, including deep-sea cod fishing in the seas of Newfoundland, maritime trade, maritime warfare featuring colorful corsair characters such as Duguay-Trouin and Surcouf, long-haul sea voyages, and ship building. I have already posted images from the museum concerning Chateaubriand and Jaques Cartier in my posts Saint Malo and Jacques Cartier, look there for these subjects.

The “corsair” activities started in the Middle Ages, the main goals really being to compensate for economic difficulties in times of war. The ship owners did not accept that the war had to be an obstacle to their trade. Jean de Châtillon, who was the bishop of Saint-Malo, in 1144 gave the entire town of Saint-Malo the status of rights of asylum which encouraged all manner of “thieves and rogues” to move there. Their motto was “Neither Breton, nor French, but from Saint-Malo am I!”. The rock of St-Malo was only connected to the mainland by a narrow causeway of sand and it was this natural defense that induced the population to move away from Aleth during the period of Viking raids. The solid ramparts seen today in Saint Malo were added by Bishop Châtillon in the 12th century. French corsaires were privateers, authorized to conduct raids on shipping of a nation at war with France, on behalf of the French crown. Seized vessels and cargo were sold at auction, with the corsair captain entitled to a portion of the proceeds. Although not French Navy personnel, corsairs were considered legitimate combatants in France (and allied nations), provided the commanding officer of the vessel was in possession of a valid Letter of Marque (Lettre de Marque or Lettre de Course), and the officers and crew conducted themselves according to contemporary admiralty law.

Jean-François Roberval was a French nobleman and adventurer who, through his friendship with King Francis, became the first Lieutenant General of New France, replacing Jacques Cartier. Roberval was born in Carcassonne, southern France around 1500. As a young nobleman, Roberval joined the French army in the Italian campaigns. He quickly developed a lifelong friendship with the future King Francis, and in addition to soldiering together, they hunted on the Roberval estates. When his appointment as the first Lieutenant General of New France did not work out, he attempted to pay off his debts through privateering. The Spanish Caribbean was his main target, since at that time France and Spain were at war. Known to the Spanish as Roberto Baal, in 1543 he sacked Rancherias and Santa Marta, followed by an attack in 1544 on Cartagena de Indias. In 1546, ships under his command attacked Baracoa and Havana. The next year, he retired from pirating. Between the early 1500s and 1713 when the signing of the treaty of Utrecht effectively put an end to the French corsair raids in the Caribbean, the Guerre de Course, as the French called it, took a huge toll on the Spanish Treasure Fleet’s efforts to ship the gold and silver from Peru to Santo Domingo and La Havana and then on to Spain.

Jean Fleury was a 16th century French naval officer and privateer, best known for the capture of two out of the three Spanish galleons carrying the Aztec treasure from Mexico to Spain in 1522. This was one the earliest recorded acts of piracy against the new Spanish Empire and encouraged the French Corsairs, Dutch Sea Beggars and English Sea Dogs to begin attacking shipping and settlements in the Spanish Main during the next several decades.

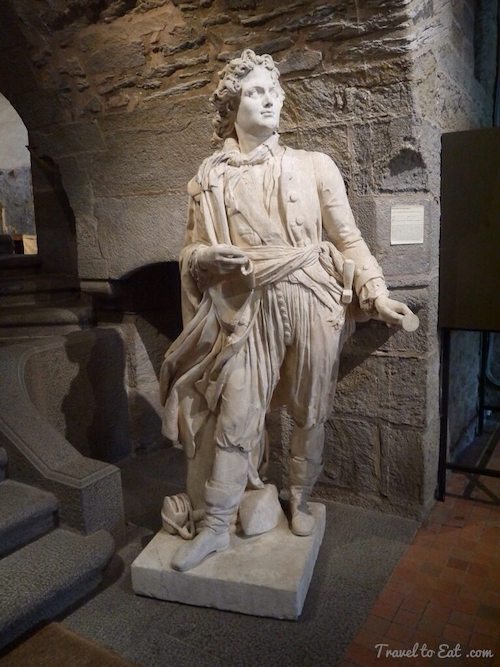

René Trouin, usually called René Duguay-Trouin, was a famous French corsair of Saint-Malo. René Duguay-Trouin was born in Saint-Malo in 1673, the son of a rich ship owner with a fleet of 64 ships and was honored in 1709 for capturing more than 300 merchant ships and 20 warships. He had a brilliant privateering and naval career and eventually became “Lieutenant-General of the Naval Armies of the King”, i.e., admiral, (French:Lieutenant-Général des armées navales du roi), and a Commander in the Order of Saint-Louis. He died peacefully in 1736. Ten ships of the French Navy were named in his honor. Everyone loves a good pirate and Trouin was one of the best.

In October 1707, together with Claude de Forbin, he achieved his greatest victory against a British squadron, in the Battle at the Lizard. In September 1711, in an 11-day battle, he captured Rio de Janeiro, then believed impregnable, with twelve ships and 6 000 men, in spite of the defense consisting of seven ships of the line, five forts and 12 000 men; he held the governor for ransom. Investors in this venture doubled their money, and Duguay-Trouin earned a promotion to Admiral.

Robert Surcouf was the last and best known corsair of Saint-Malo. Born there in 1773, his father was a ship owner and his mother the daughter of a captain. Ship’s boy at 13 and corsair captain at 22 years old, and then, very much against his license, for several years attacked ships including those of the French East India Company, or Compagnie Française des Indes. During the French Revolution, the convention government disapproved of lettres de course, so Surcouf operated at great personal risk as a pirate against British shipping to India. Surcouf was so successful that he became a popular celebrity in France. After a brief early retirement Surcouf again operated against shipping to the Indies. Surcouf became a ship owner himself and died in Saint-Malo in 1827. Through Surcouf’s actions he brought incredible wealth to St. Malo, it was said that Napoleon himself borrowed from the city’s treasury to pay for his campaigns.

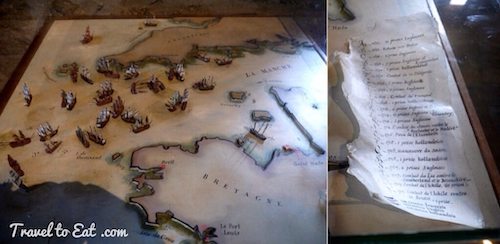

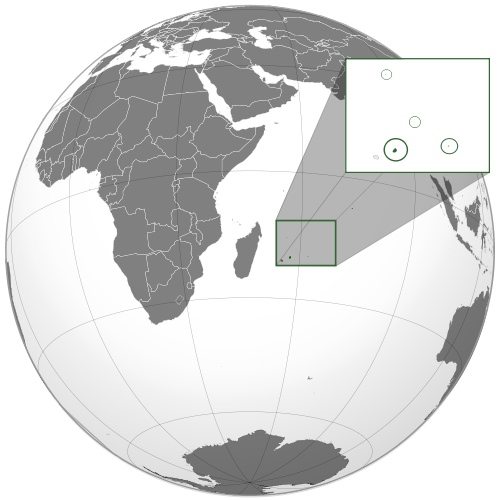

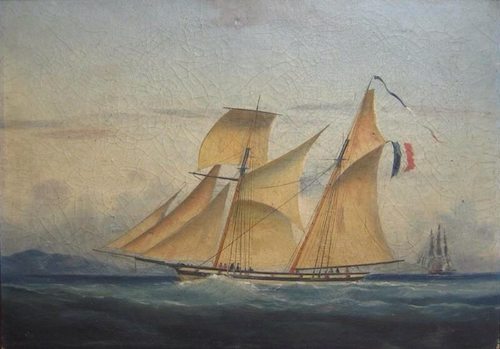

This beautiful marine painting commemorates one of the first victories of Robert Surcouf, then aged 23, by Trémisot Leo, a talented painter of the second half of the 19th century who also worked at the time for the city of Saint-Malo. On 3 June 1794, Surcouf sailed with the 4-gun ship La Créole, with a complement of 30 men, with orders to bring rice to Mauritius, and encountered three English ships escorted by the 26-gun Triton. Since he did not have lettres de course, he used a technicality to engage combat in self-defence, by not flying his colours until the English ships requested them by firing a warning shot (a naval convention of the time), which Surcouf later reported to consider an aggression. After a brief gunnery exchange, the British ships lowered their flag and were brought back to Mauritius, with their cargo of rice and maize. Surcouf was welcomed as a saviour in the famished Port Louis, Mauritius. The capture was declared legal, but in the absence of a letter of marque, the authorities retained the entire cargo (a portion of which normally goes to the corsair). During the Napoleonic Wars, Mauritius became a base from which French corsairs organized successful raids on British commercial ships.

In May 1800, Surcouf took command of Confiance, a fast 22-gun ship from Bordeaux undergoing repairs in Isle de France (Mauritius). Beginning in March, he led a brilliant campaign which resulted in the capture of nine British ships. On 7 October 1800, in the Bay of Bengal, off Sand Heads, Confiance met the 26-gun Kent, an 820-ton East Indiaman, under Captain Robert Rivington with 437 men. The French managed to seize control of the Kent. He became a living legend in France and, in England, a public enemy whose capture was valued at 5 million francs, although he was noted for the discipline of his crew and his humane treatment of prisoners.

As a privateer, Surcouf used tactics to compensate for being outgunned by larger British ships. He would use small, fast ships to make the huge ships think he was either not enough of a threat to consider firing at, a vessel on the verge of sinking, or a fishing vessel. Even if the enemy did fire at him, his ships were often too fast for the British behemoths to catch. When alongside an enemy ship, elite marines waited belowdecks until an order was given to board. When the men sprang forth, the British ship cannons could not depress enough to fire directly on the French ship.

The museum has a nice collection of old firearms and various pirate gear. I especially like the gruesome collar with spikes on the inside.

They also have some rare old nautical instruments. The Portuguese nautical astrolabe is particularly rare (see my post on Astrolabes and Sundials). The Madre de Deus, returning from the East Indies and headed for Lisbon was captured by the English 1592 near the Azores. Built in Lisbon in 1589, she was returning from her second voyage East. She was 165 feet in length, had 47 feet of beam, weighed 1,600 tons (of which 900 were cargo) — three times the size of England’s biggest ship. Among the riches were chests filled with jewels and pearls, gold and silver coins, ambergris, rolls of the highest-quality cloth, fine tapestries, 425 tons of pepper, 45 tons of cloves, 35 tons of cinnamon, 3 tons of mace and 3 of nutmeg, 2.5 tons of benjamin (a highly aromatic balsamic resin used for perfumes and medicines), 25 tons of cochineal and 15 tons of ebony.

She was brought back to Dartmouth harbor on September 7, towering over the other ships and the town’s small houses. Nothing like it had ever been seen in England and pandemonium broke loose. Madre de Deus attracted all manner of traders, dealers, cutpurses and thieves, apparently some were from Saint Malo. They visited the floating castle and sought out drunken sailors in taverns and pubs, buying, stealing, pinching and fighting for the takings. Local fishermen as well would constantly venture aboard and back to shore, further depleting the cargo. English law at the time provided that a large share of the loot was owed to the sovereign, and when Queen Elizabeth found out what was happening, she sent Sir Walter Raleigh to reclaim her money and punish the looters. By the time Raleigh had restored order, a cargo estimated at half a million pounds (nearly half the size of England’s treasury and perhaps the second-largest treasure ever after the Ransom of Atahualpa) had been reduced to £140,000. Still, ten freighters were needed to carry the treasure around the coast and up the River Thames to London.

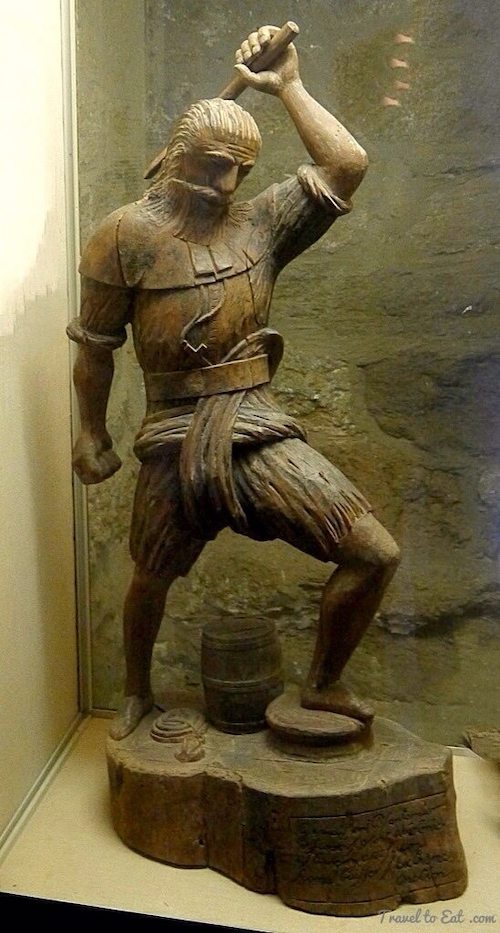

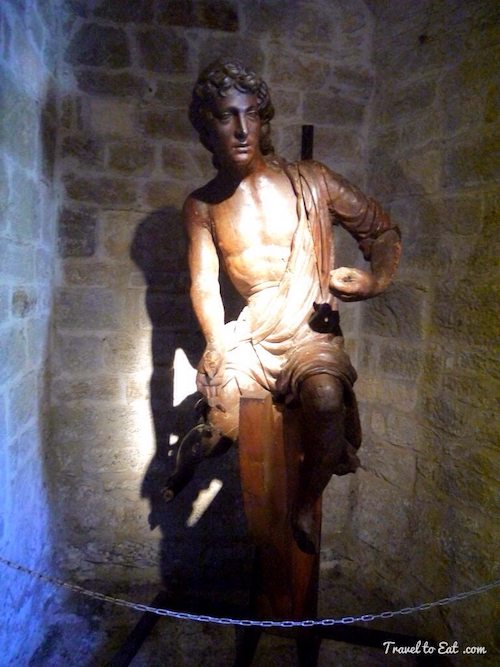

They have some great wooden carvings including the 20 foot tall figurehead shown above. I have read some disparaging reviews of the Musée d’Histoire de St Malo but I found the experience delightful. If you come with a little knowledge of the history of Saint Malo and enjoy nautical stuff, you will have a great time. Personally, I have never been to a pirate museum and if you have kids I think you will particularly like this little museum. Of course if you climb the stairs to the top of the museum, go to the top and take in the best view in town.

References:

Saint Malo Website: http://www.ville-saint-malo.fr/galeries-dimages/musee-dhistoire-chateau-et-tour-solidor/

Corsaires: http://tatihou.manche.fr/Expositions/Corsaires/index.html