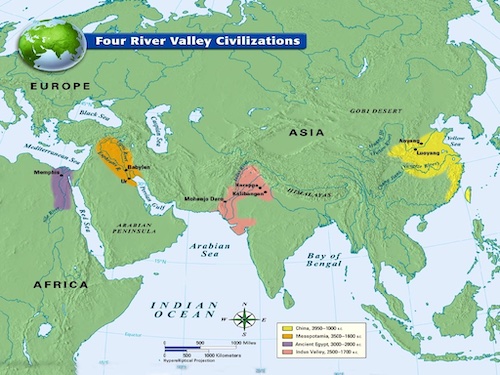

In the great river civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and China, pastoralists preceded the true neolithic settlers. The initial domesticated animals included cattle from wild Auroch, sheep and goats from their wild equivalents. Pigs and Fowl followed later and have an intertwined history. As time progressed, irrigation along rivers allowed large scale farming and the establishment of permanent communities. With the advent of these communities came inevitable population increases and increased pressures concerning the utilization of available resources. Fortunately, at first there was plenty for all but climate changes around 2500 BCE contracted the availability of arable land and led to conflict. This whole narrative is nicely summarized in the “Tragedy of the Commons”, an economic theory proposed by William Forster Lloyd in 1833 that is still relevant today. I suggest you read it but for now let us continue with the history of the chicken, a mobile source of protein more suited to mixed farming, unmatched in both the ancient and modern world.

Chickens and Junglefowl

Chickens became very important to early Egyptian, Greek and Roman farmers and continue to be an important source of food in today’s economies. Modern domestic chickens all descended from one of the four known species of jungle fowl or Gallus habituating areas of Southeast Asia, around 50 million years ago. The earliest undisputed domestic chicken remains are bones associated with a date of approximately 5400 BC from the Chishan site, in the Hebei province of China. In the Ganges region of India Red Junglefowl were being exploited by humans as early as 7,000 years ago. No domestic chickens older than 4,000 years have been identified in the Indus Valley, and the antiquity of chickens recovered from excavations at Mohenjo-daro is still the subject of some debate.

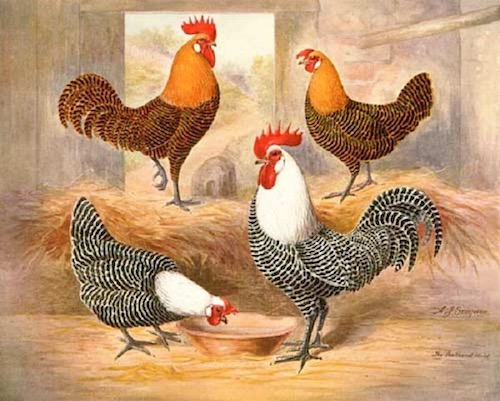

The wild species of Gallus that may have contributed to the domestic fowl include the Red Jungle Fowl (Gallus gallus), Grey Jungle Fowl (Gallus sonnerrati), Sri Lanka/Ceylon Fowl (Gallus lafayettei) and the Green/Java Fowl (Gallus vanus). A gene from the grey junglefowl is responsible for the yellow pigment in the legs and different body parts of all domesticated chickens. This species is endemic to India, and even today it is found mainly in peninsular India and towards the northern boundary. It will sometimes hybridize in the wild with the red junglefowl. It also hybridizes readily in captivity and sometimes with free-range domestic fowl kept in habitations close to forests. It is a barbaric but true historical fact that chickens were first domesticated in China, Persia and Southeast Asia to use as fighting cocks, a tradition which is still practiced today, particularly in India and Pakistan.

Asil or Aseel Chicken

The Asil or the Aseel is a chicken breed that was bred in India over 2–3 thousand years ago as a fighting bird. It’s one of the oldest game breeds and through selective breeding became one of the largest and most muscular cock fighting breeds. The name Asil is an Arabic name, and means “of long pedigree”. It is likely that the Asil are descended from the first chickens introduced to the Indus Valley. For those who are a little rusty on their Indian history, the Indus Valley civilization (current day Pakistan) thrived from about 3500–1500 BCE. They were replaced by the Aryans, a migration of people from the Sintashta culture located roughly in the Caucasus (southern modern day Ukraine) into the northern Indian subcontinent (modern day India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan). These migrations started approximately 1,800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia, according to David Anthony author of the “Wheel and Language“. The Aryans populated both the Ganges and the Indus river valleys and established the “caste system” in India, based largely on skin color.

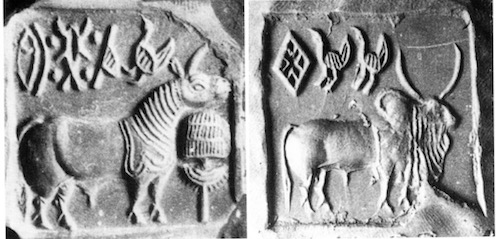

Mohenjo-daro Indus Valley

Mohenjo-daro or Moenjo-daro (translated Mound of the Dead) is an archaeological site in Sindh. Built around 2600 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization, and one of the world’s earliest major urban settlements with well-planned cities. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE. The city’s original name is unknown, but analysis of a Mohenjo-daro seal suggests a possible ancient name, Kukkutarma (“the city of the cockerel”). Cock-fighting may have had ritual and religious significance for the city, with domesticated chickens bred there for sacred purposes, rather than as a food source. Mohenjo-daro may have been a point of diffusion for the eventual worldwide domestication of chickens. I would like to comment on the archeological significance of the toy chicken with wheels. I know nothing more about it other than the fact that it was found in Mohenjo-daro and resides in a museum in India. Since the wheel was thought to be invented in the Caucasus region of southern Ukraine, it represents a quite significant find.

Lothal

It is tempting to argue that if the chicken first emerged in the Indus Valley, then it must be a Punjabi bird. After all, the cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro are now in Pakistan and the boundaries of the Indus Valley Civilisation were thought to cover only modern Punjab and Sindh. But recent archaeological evidence suggests that the Indus Valley Civilisation actually covered a much larger area and Lothal, where the first chicken bones have been found, is near present-day Ahmedabad in India. From the mounds of chicken bones found around the dockyard one can suppose that chickens were being prepared at the site for a long journey to Mesopotamia and/or Egypt. Cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia dating to 2000 BCE refer to “the bird of Meluha”, which was their name for the Indus Valley Civilisation. I just happened upon a translator of the ancient Indus or Meluhan language, Shu-ilishu, who lived around 2020 BCE during the late Akkadian period. His cylinder seal is shown above, too bad he is gone, we still cannot read this ancient language.

Megiddo and the Lakenvelder Chickens

Megiddo is the home to the ancient city of Megiddo, called Armageddon in Greek from Har Megiddo “mount of Megiddo” in Hebrew. Megiddo is located at the head of a pass through the Carmel Ridge on an ancient trade route between Egypt and Mesopotamia. This strategic location made the city an important site for millennia. According to legend, some 2,000 years before the birth of Christ, there was an immigration of Indo-Aryan wise men whom upon arrival in Mesopotamia, became known as the Holy men of the Brahmaputra River, or Ah-Brahman. These men brought with them, from the Indus Valley, the first domestic chickens. Some of the Ah-Brahman settled in Palestine, at the city of Armageddon, also known as Tel Megiddo – where they bred their fowl, valuing it primarily for the crow of the roosters and, later, for the eggs. One of the first people to incorporate chicken eggs into baking bread may have been the Jews, creating challah and perhaps later in France, Brioche. Around 1 A.D., Jewish immigrants to Holland and Germany brought with them their Tel Megiddo chickens. So it is that the ancestors of the Lakenvelder chicken arrived in Europe.

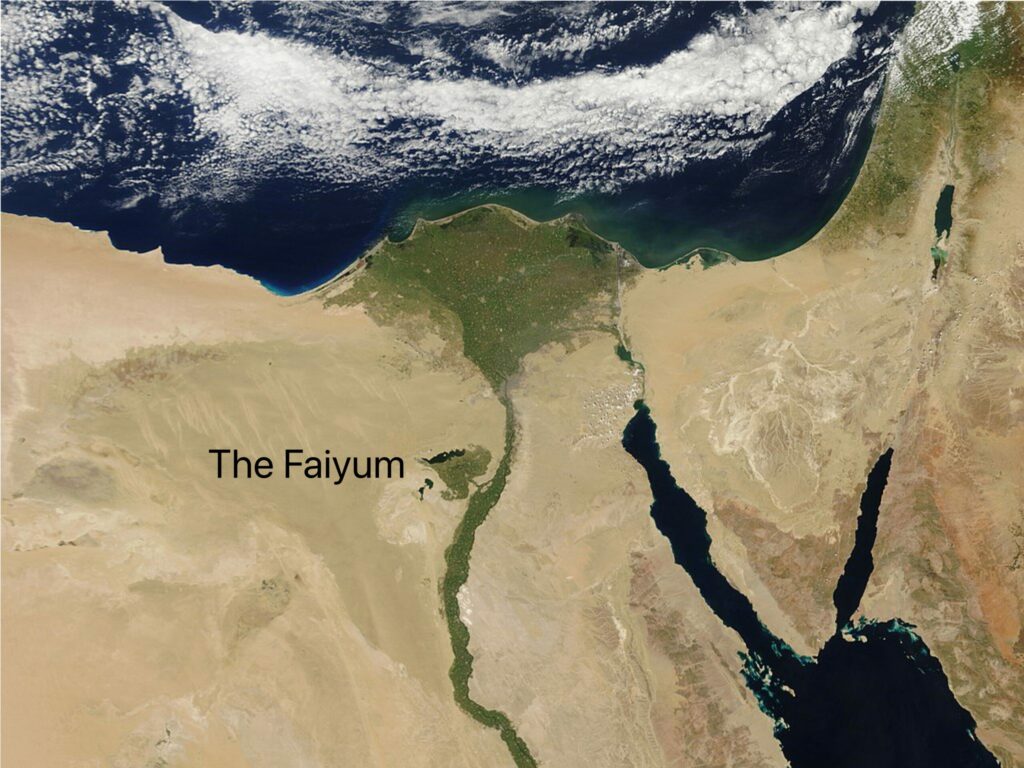

The Faiyum Oasis

The Faiyum (also given as Fayoum, Fayum, and Faiyum Oasis) was a region of ancient Egypt known for its fertility and the abundance of plant and animal life. Located 62 miles (100 kilometers) south of Memphis (modern Cairo), the Faiyum was once an arid desert basin which became a lush oasis when a branch of the Nile River silted up and diverted water to it well before recorded history. In 2007, the ruins of an older farming community was discovered in the Faiyum dating to 5200 BCE and pottery has also been found dating to 5500 BCE. It should be noted that these dates relate only to established agrarian communities, not to human habitation of the Faiyum region which dates to 7200 BCE. The Eleventh Dynasty’s capital was located at the city of Thebes. The first king of the Twelfth Dynasty, Amenemhet I (1991–1962 BC), moved the capital from Thebes to a city near el-Lisht called Itj-tawy, because it was close to the mouth of the Faiyum. He enhanced water flow to the area and the Faiyum prospered. Under Amenemhat III the waterway from the Nile to the natural lake was widened and deepened to make a canal that now is known as the Bahr Yussef. This canal fed into the lake. This was meant to serve three purposes: control the flooding of the Nile, regulate the water level of the Nile during dry seasons, and serve the surrounding area with irrigation. There is evidence of ancient Egyptian pharaohs of the twelfth dynasty using the natural lake of Faiyum as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry periods.

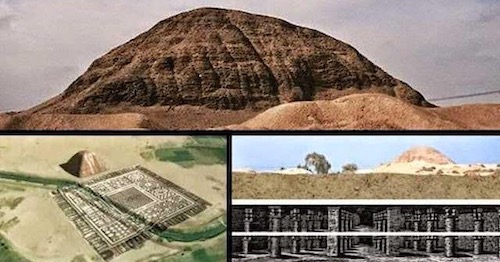

Labyrinth of Hawara

Herodotus (fifth century B.C.) and other Greek and Roman writers described a magnificent labyrinth in Egypt, containing 12 palaces and three thousand rooms on two levels. Herodotus wrote that the labyrinth was “situated a little above the lake of Moiris and nearly opposite to that which is called the City of Crocodiles” (‘Histories’, Book, II, 148). Pliny the Elder (first century A.D.) related that the Egyptian labyrinth was already 3600 years old in his time. Just south of the site of Crocodilopolis, at the entrance to the depression of the Faiyum Oasis, sits Hawara, an archaeological site that is home to the pyramid of Amenemhat III, the last king of the 12th dynasty (c 1855–1808 BC). It is here where William Flinders Petrie made a significant discovery in 1889. Petrie discovered an enormous artificial stone plateau measuring 304m by 244m, which he interpreted as being the foundation of the labyrinth. He concluded that the labyrinth itself must have been destroyed in antiquity and that all that was left was the stone base. In 2008 the ‘Mataha Expedition’ discovered amazing proof of the Labyrinth’s existence. Using GPS instruments, the team found “the presence of a colossal archaeological feature below the labyrinth ‘foundation’ zone of Petrie’s record, which has to be reconsidered as the roof of the still existing labyrinth.” Unfortunately, the underground area appears to have been flooded and no further results are forthcoming.

Of more interest to our subject of chickens, Herodotus noted a large number of wild chickens in the surrounding Faiyum.

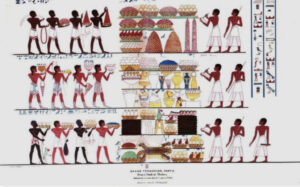

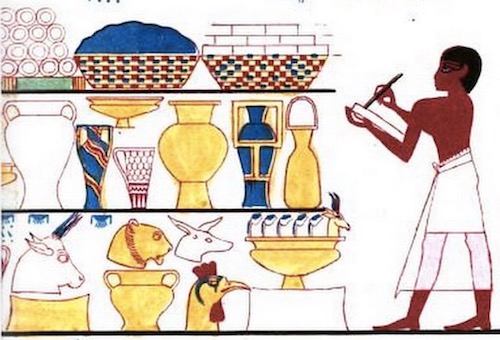

Chickens in Egypt

There is no recorded mention of the domestic chicken in Ancient Egypt before the Middle Kingdom (2134–1786 BCE). Coltherd mentions graffiti on the stones of an Egyptian temple on which the names of kings from the twelfth and thirteenth dynasties appear. At Thebes in upper Egypt, a mural depicting a rooster’s head was found in the tomb of Rekhamara, who was vizier to Thutmose III (ca. 1450 BCE). Of interest is the fact that these were gifts from Ethiopia, a country adjacent to ancient Punt or later Axum, a major trading location with the trade from India. This brings up the possibility that these roosters came directly from India and that chickens in the rest of Africa were sourced as well. An ostracon (flake of stone with writing) found outside the tomb of Tutankhamun, and presumably dating to the time of his burial (1347–1338 B.C.E.), also clearly depicts a rooster. There is little evidence that the chickens were more than curiosities, much like the peacocks of the Romans or the Alexandrine parakeets of Istanbul. As is the case for the Alexandrine parakeets, the chickens eventually were released into the wild and became naturalized in the Faiyum Oasis, as they are today.

Legends of Chickens in the New Kingdom

Carved on the walls of Karnak in Egypt is a well-preserved description of how Pharaoh Thutmosis III, one of Egypt’s greatest sovereigns and her finest military strategist, fought a coalition of Syrian princes at Megiddo in 1469 BC. The Syrians had occupied Megiddo and controlled the pass through the Carmel ridge, the Wadi ‘Ara. Thutmosis moved a large army from Egypt through the Wadi ‘Ara surprising the Syrian princes who had anticipated that the Egyptian army would come through the two other, less dangerous, routes. In the ensuing battle the Syrians were able to escape to the safety of Megiddo where, after a seven-month siege, the city fell. After the siege, the amount of agricultural spoils captured by Thutmosis is impressive: “…1,929 cows, 2,000 goats, and 20,500 sheep…[The] of the harvest which is majesty carried off from the Megiddo acres: 207,300 [+ x] sacks of wheat, apart from what was cut as forage by his majesty’s army…” (Pritchard 1958: 181–82). It is estimated the wheat, alone, measured 450,000 bushels (Pritchard 1958: 182 n.1). Megiddo was a very wealthy and fertile target, indeed. In fact, this victory encouraged Thutmose to return almost annually to enlarge the Egyptian Kingdom in the Levantine. Legend has it that he also returned with a number of Megiddo chickens although I can find no references to this point.

About 70 years after the Battle of Tel Megiddo, scores of dazzling male Sri Lanka Junglefowl reportedly arrived along with a major tribute of cinnamon from Sri Lanka during the reign of Thutmose’s great grandson, King Amenhotep III. According to legend, the Asil chickens from Magiddo and the Sri Lankan/Ceylon Junglefowl from Ceylon were taken to the palaces at the labyrinth in the Faiyum and allowed to run free. Over the years, as the desert steadily encroached, most of the people left Fayoum. The fowl, hardy birds, hung on and adapted to flourish in the marshes amongst the reeds. They foraged in the thorn forest and took shelter in the dense palm forests surrounding the evaporating lake bed. For the next thousand years, this population bred on its own in isolation from other influences. The addition of the Sri Lankan/Ceylon Junglefowl, bred in dry scrub habitats, to the Asil breed strengthened and energized the breed and eased the transition to the semi-arid Middle East climate. Note the white spot on the earlobe of the Sri Lankan/Ceylon Junglefowl.

Pigs vs Chickens

Redding (see references) has suggested that in the Levant chickens came to replace pigs as an important economic species in the first millennium BCE. In contrast to large herd animals, both taxa could be reared on a smaller household scale, engendering relatively little interest from central authorities, artists, or historians. Both taxa would have exerted similar demands (food and labor) on the household economy, thereby likely competing for these resources. However, as opposed to the low mobility and high water consumption of pigs, chickens provided an easy-to-grow, compact, and highly portable package of meat and a more efficient source of protein through both its eggs and meat. A critical factor contributing to tipping the balance in favor of chickens over pigs would have been the harvesting of eggs, which were a new, accessible source of protein. The conditions for developing a flourishing chicken economy seem to have been well met at Maresha. Interestingly, in China and Southeast Asia, chickens, ducks and pigs were all kept possibly due to the wet climate.

Spread of Chickens in the Mediterranean

Seals bearing the images of roosters discovered at Nimrud indicate that chickens were kept in Assyria by the eighth century BCE. Chickens appear to have been introduced to the peoples along the Mediterranean coast beginning in the eighth century BCE and became common throughout Greece and Asia Minor by the sixth century BCE. Again, even though chickens were depicted in these areas, they were used for display and cockfighting. Eating these relatively rare birds or eating their eggs was either against religion or law and probably more importantly was financially inadvisable.

Eating Chickens and Eggs in Maresha

Because of its long history among humans, the chicken has been linked with all kinds of mythology and folklore through the ages. In Greek mythology it was a sacred bird of the Athena, goddess of wisdom and warfare, a bird of fertility for Persephone, a clucking token of love and desire for Eros, and a symbol of commerce and productivity for Hermes. So sacred was it, in fact, that Ancient Greeks didn’t eat chicken meat, keeping the birds for eggs and religion only. The world’s first period of industrial growth of chickens and eggs for mass consumption began in Israel’s Judean lowlands of Lachish some 2,300 years ago, 200 years before the practice reached Europe, researchers at the University of Haifa announced in 2015. Senior staff at the Zinman Institute of Archaeology at Haifa University, Professor Guy Bar-Oz, Dr. Adi Erlich, and Ayelet Gilboa, along with Perry-Gal, published research on how chicken came to be a major food source in the West. At some point between 200 and 400 BCE, the residents of Maresha began raising and eating chicken, as well as eggs, which we also have no evidence was eaten before this period,” said Perry-Gal, referring to an archaeological site near the Beit Guvrin caves in central Israel. “That changed, and chicken became a part of the culinary culture of Israel and eventually the rest of the Western world.

Egyptian Faiyumi Chickens

Although the specific breed of chicken used in Maresha has not been determined, the study shows that the Hellenistic chickens of Levantine Maresha did not differ in their wing, breast, and leg dimensions from those of European chicken breeds in the Roman period. This observation challenges the hypothesis that selective breeding in Roman times caused a substantial size increase in chickens. The data suggest that this change was already evident in the Hellenistic Southern Levant. Faiyumis have a single comb, earlobes, and wattles are red and moderately large, with a white spot in the earlobes, indicating the connection with the Sri Lankan/Ceylon Junglefowl. They have dark horn colored beaks, and slate blue skin. Their appearance is remarkably similar to the silver variety of the Campine breed of Belgium, and the Campine may be descended from a Faiyumi-like chicken brought north in Europe by the Romans.

I had the opportunity to see some domestic chickens, which I think are Bigawi, when I visited Cairo. The Bigawi is a breed of the Faiyumi, differentiated from the Modern Fayoumi by size, color and temperament. The Bigawi is a bit smaller and battier than the Fayoumi. Females are a rich chestnut brown with bold black transverse barring. Males are difficult to discern from Modern Fayoumi, though they tend to be darker in the wings with darker and longer tails. Both Bigawi and Modern Fayoumi should have dark facial skin and an unusual crow that is distinguishable from any other breed of rooster. The wattles are reasonably large and the earlobes have a white spot, just as with the Sri Lankan/Ceylon Junglefowl. In Kassala and Port Sudan in Eastern Sudan, one sees Bigawi fowl that are pewter in color. They are camouflaged against the dark soil there. Their combs are very like those of the Sicilian Buttercup, another breed with African roots. Many Bigawi roosters are white with grey barring appearing only on the breast or undertail. They are a land race and as such there is some diversity amongst them. The Shakshuk Fayoumi is the common strain of unimproved Fayoumi that one sees in villages throughout the Fayoum and in the cemetery of Old Cairo. They are brightly colored with vivid yellow legs and ginger hued feathers. I believe the Faiyumi are one of the major breeds taken with the Romans to Europe.

Other Roman Gamefowl

The acceleration of Mediterranean economic interconnections in Roman times, beginning in the first century BCE, would have provided the conditions for intensifying chicken exploitation in Europe as well. The Romans introduced to Europe a variety of plant and animal species. Egyptian guineafowl (Numida Meleagris), pheasant from Colchis on the Black Sea (Phasianus colchicus), rabbit from Morocco/Spain (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and they also were responsible for the introduction of the chickens from the Southern Levant. The mechanism behind the initial introduction of the Southern Levantine chicken may have been the supply of novel foods to urban markets, satisfying a need created by feasts, both public and private. Their small size and relative ease of transport and management meant that chicks and chicken eggs were exchanged easily between areas of agricultural production (pastio villatica) and urban centers, as described in several literary sources. In Roman Britain, higher proportions of chicken remains were uncovered in urban than in other types of sites. It has been suggested that chicken was, at least in the beginning, a luxury food, consumed by the Roman upper classes. Other avian species such as the peacock (Pavo cristatus) and flamingo (Phoenicopterus spp.), which initially were kept for their ornamental qualities and symbolic characteristics, were beginning to be regarded as a delicacy under the Late Republic when Quintus Hortensius introduced them to the Roman table, although they never really caught on.

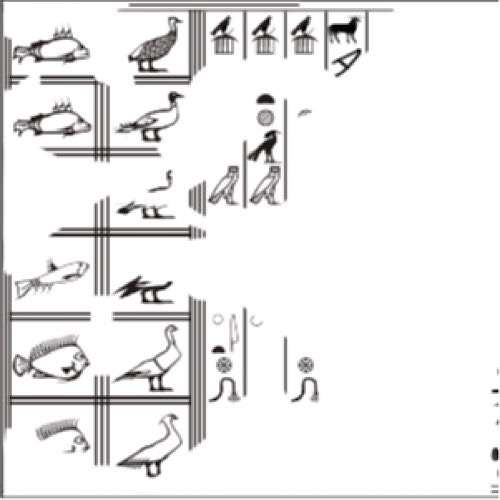

Guineafowl in the Ancient World

The advent of Guinea fowls in the history of human activity is traced back to the Egyptian fifth dynasty about 2,400 B.C. when its figure was drawn on the Giza Writing Board. Early domestication is supposed to have occurred in Southern Sudan and West Africa. There were at least several independent domestications involving more than one subspecies. The Gardiner hieroglyph G21 is a guineafowl. The Giza writing board (also named Giza king list) is an Ancient Egyptian artefact created during the late Fifth Dynasty (c. 2494 – c. 2345 BCE) or early Sixth Dynasty (c. 2345 – c. 2181 BCE). It was found in the burial place of a high official named Mesdjerw and his wife Hetep-neferet. It contains an image of a guineafowl. Although some sort of Guinea Fowl are said to have been held in domestication by the ancient Egyptians (about 1475 BC), Greeks (about 500 BC), and Romans (by AD 72), these later died out in Europe. The modern domesticated Guinea Fowl originated from one of several wild species on what used to be called the Guinea Coast (hence the name) of West Africa. There appear to be no references to guineafowl in the Middle Ages until Portuguese sailors gave the bird it’s present name in the 16th century.

Helmeted Guineafowl

The helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris) is the best known of the guineafowl bird family, Numididae, and the only member of the genus Numida. It is native to Africa, mainly south of the Sahara, and has been widely introduced into the West Indies, Brazil, Australia and Europe. There are nine subspecies, this one is Numida meleagris damarensis which occurs from arid southern Angola to northern Namibia and northern Botswana. The helmeted guineafowl is a large 21–23 in (53–58 cm) bird with a round body and small head. They weigh about 2.9 lb (1.3 kg). The body plumage is gray-black spangled with white. Like other guineafowl, this species has an unfeathered head. In this species it is decorated with a dull yellow or reddish bony knob, and bare skin with red, blue or black hues. The wings are short and rounded, and the tail is likewise short. Guinea fowl have long been considered a prized game bird, right up there with pheasants and quail. Understandably, the Egyptians considered the guineafowl a luxury food for the wealthy. Guineas are gaining in popularity in the U.S., outselling their pheasant and quail friends although I do think they are more popular in Australia and Europe. Keeping guineafowl is more like they keep you. They are noisy, roost in trees but they do eat the bugs without tearing up the garden.

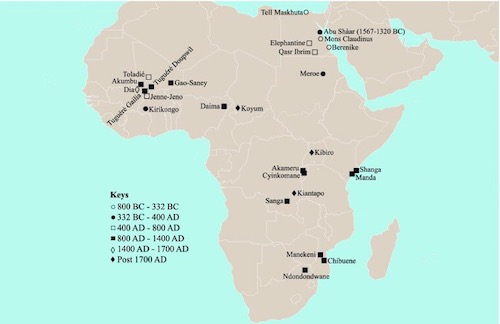

Chickens in Sub-Saharan Africa

I would be remiss if I did not carry this story a bit further. We know what happened to the chicken in Europe after the Romans but what about Africa? Guinea fowl is both a domestic and wild bird in most parts of Africa, and their skeletal remains, as well as those of the spurfowl, often occur concurrently with those of domestic chickens on many archaeological sites, complicating identification. Pternistis is a genus of galliform birds (in the same family as domestic chickens) in the partridge subfamily of the pheasant family. Its 23 species range through Sub-Saharan Africa. They are commonly known as francolins or spurfowl but are closely related to jungle bush quail, Alectoris rock partridges and Coturnix quail. Fortunately some data for domestic chickens is available as shown above. We see that chickens were introduced to the majority of Africa before European contact.

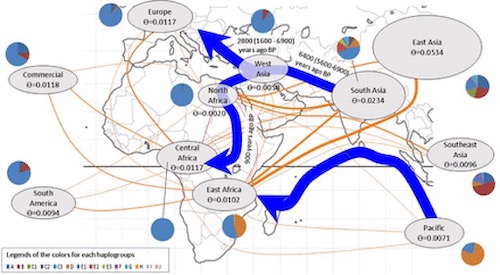

Recent DNA analysis (J. M. Mwacharo et al 2013 and Sayad Osman et al. 2016) shows a surprising origin of these chickens. They found that most of the chickens came from Egypt and Somalia (ancient Punt/Axum) but characterized by multiple introductions over time and several dispersal routes towards and within Africa. Molecular genetics information supports these observations and in addition suggests possible Asian centers of origin for African domestic chickens, including South Asia and Island Southeast Asia/Polynesia, possibly through Madagascar. It raises the interesting hypothesis that its arrival might have followed the Chinese maritime trading expeditions across the Indian Ocean. A pretty surprising result.

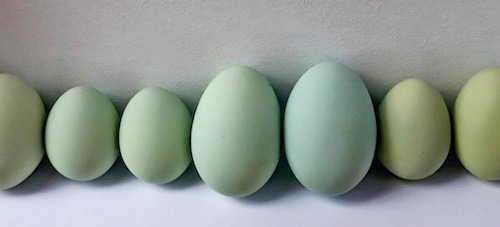

Pre-Columbian Araucana

The Araucana is a breed of domestic chicken from Chile. Its name derives from the Araucanía region of Chile where it is believed to have originated. It lays blue-shelled eggs, one of very few breeds that do so. There has been a long debate about the origin of the Araucana and whether it derives from chickens brought by Europeans after Columbus reached the Americas in 1492, or if it was already present. A report published in 2007 (Storey et al .. see below) on chicken bones found on the Arauco Peninsula in south-central Chile suggested pre-Columbian, possibly Polynesian, origin. I personally do not find this implausible since Easter Island is not that far from Chile.

I have tried to present this history of poultry with some objectivity, separating legends from known facts but there is bound to be overlap, especially with such an all encompassing subject as the origins of the most common farmyard animal in the world. We live in an amazing era in which chemical samples of tissue and blood can relate intricate stories of migration of not only people but the animals and plants that accompanied them. I hope that you enjoyed the post, please leave a comment.

References:

Domestication of Chickens Using DNA 2012

Chickens in Indus Valley 2500 BCE

Egyptian Fayoumi Chicken Breed

Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia

Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia

Reddeing et al. Pig and Chicken in the Middle East

Domestication and Adaptive Breeding of African Bush Fowl