Boundary markers for property are a very old concept. They are mentioned in the Bible: Proverbs 22:28 “Do not move an ancient boundary stone set up by your forefathers.” The Residence Act of July 16, 1790, as amended March 3, 1791, authorized President George Washington to select a 100-square-mile site for the national capital on the Potomac River. He selected the site and placed 40 stone markers at one mile intervals, marking the extent of the capital city. The stones are now the oldest federal monuments in the United States.

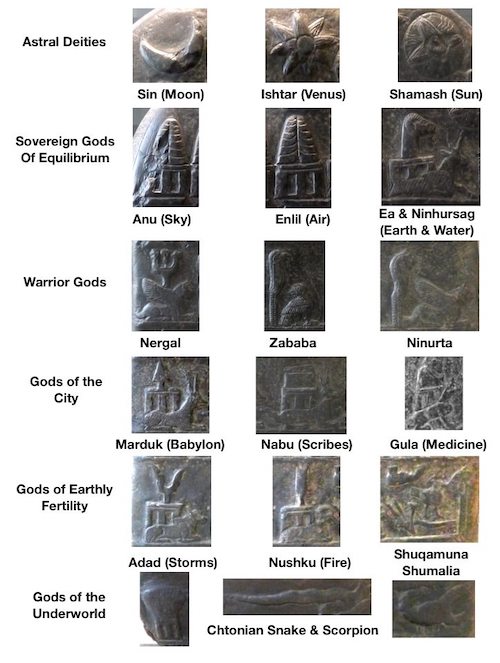

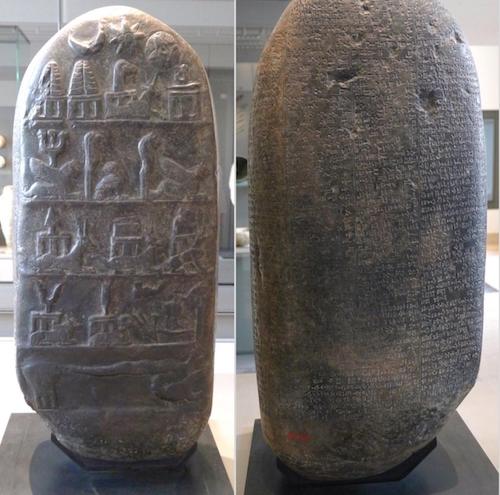

The stone shown above is even older, it is a Kudurru, a small stone stele recording a royal gift of land, from ancient Babylonia, and the concept is exactly the same as a boundary stone. The word is Akkadian for “frontier” or “boundary”. This kudurru is from the reign of King Melišipak (1186–1172 BC) at the Louvre. It records a land grant to his son, Adad-šuma-u?ur or Meliši?u. Meli means servant or slave, Šipak was a moon god, but Ši?u was possibly one of the Kassite names for Marduk, patron God of Babylon. On the front of the stele is represented the entire pantheon of gods who preserve the order of the world. The artist has used a formula that was later to be developed on other kudurrus, presenting the symbols associated with each deity in hierarchical rows. On the reverse side is cuneiform writing describing the gift and the responsibilities to the king as a result of the gift. This is followed by a section calling down a divine curse on anyone who opposed the gift. The gift was thus not only recorded and displayed for all to see, but also placed under divine protection. Because stone was precious in Babylon, the original was kept in a temple and clay replicas were placed on the land.

In the kudurru pictured above King Melišipak, with his hand over his mouth as a sign of respect, is shown presenting his daughter to the goddess Nannaya. As noted above, the crescent moon représents the god Sîn, the sun representing the god Shamash and the star (Venus) representing the goddess Ishtar. His daughter ?unnubat-Nana(ja) was the recipient of a land grant, which her father had purchased on her behalf, disproving a theory of Kassite feudalism that all land belonged to the Monarch. With the exception of the relief shown above, there are no further inscriptions. The surface is hammered, suggesting the original inscriptions have been removed, perhaps by the Elam King Shutruk-Nakhunte.

The kudurru pictured above is unfinished, without text. You can see some of the same now familiar symbols at the top. In the top row, the crowns with six rows of horns placed on the altars are the emblems of Anu, the sky god, and Enlil, the air god. To the left, the ram’s head and the goatfish representing Ea, the god of fresh water, and Ninhursag, the earth goddess. To the right, the sun of Shamash and the star (Venus) of Ishtar. At the bottom you can see the scales of the Chtonian underworld snake winding around the stone and in the picture to the right, you can see the head and tail. Also on this view you can see three symbols on the third row, the plow of Ningirsu followed by the birds of Shuqamuna and Shumalia, the divine couple of the Kassite pantheon. At the top is Marduk, represented by a horned dragon, Adad, shown with a storm on an alter and Nabu, Marduk’s son and the god of scribes, represented by a tablet and calamus. The middle row is very unusual. It depicts a procession of eight figures, all carrying bows and wearing the horned crowns that mark them out as gods, probably minor deities. Seven of the figures are bearded gods, playing the lute and accompanied by animals. A goddess playing the tambourine and possibly dancing follows them. These emblems were difficult to interpret, even for the ancients who sometimes inscribed the name of the gods symbolized next to the symbols themselves.

These kudurrus are important because they are the only surviving artworks for the period of Kassite rule in Babylonia. They were found in Susa, capital city of ancient Elam. They were taken when the Elam King Shutruk-Nakhunte, who had married the eldest daughter of King Melišipak, sacked Babylon and took them back to Elam as spoils of war. Cruel and fierce, the Elamites finally destroyed the dynasty of the Kassites during these wars (about 1155), often lamented by the poets of Babylon.

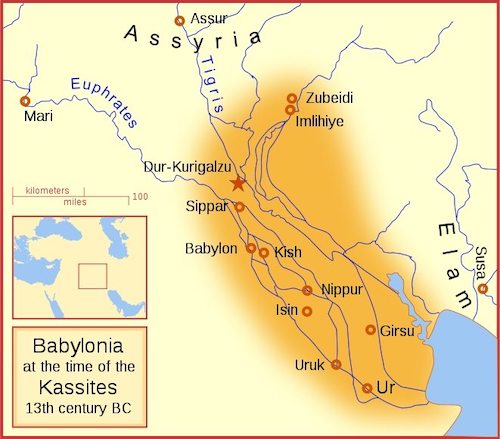

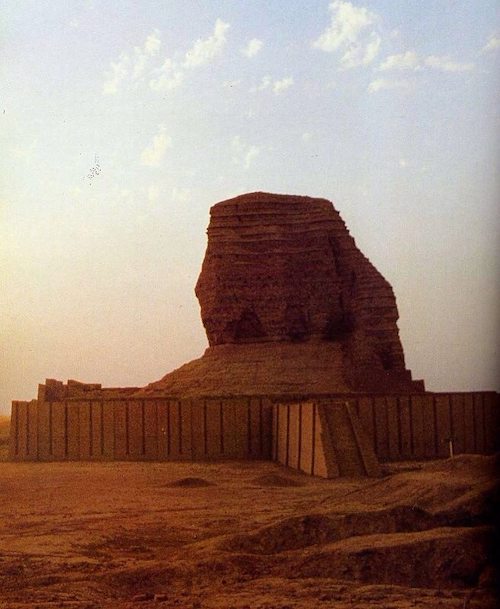

The Kassites first appeared during the reign of Samsu-iluna (1749–1712 BC), son of Hammurabi (see my post on the Code of Hamarabi) of the First Babylonian Dynasty and after being defeated by Babylon, moved to control the city-state of Mari. Babylon was invaded and captured by the Hittite king Mursilis in about 1595 BC, but he mysteriously soon left Babylon and returned to Hattusas. The Kassite ruler, Agum II, filled this power void establishing the Kassite dynasty in Mesopotamia that was to last until about 1157 BC. Some undetermined amount of time after the fall of Babylon to, the Kassites established a new Babylonian dynasty. The Hittites had carried off the idol of the god Marduk, but the Kassite rulers regained possession, returned Marduk to Babylon, and made him the equal of the Kassite Shuqamuna. They went on to to conquer the southern part of Mesopotamia, roughly corresponding to ancient Sumer and known as the Dynasty of the Sealand by 1460 BC. The Kassites restored the ancient temples of Nippur, Larsa, Ur, and Uruk, while their scholars were preserving the literature in Akkadian, the standard language of the Near East for a millennium. Much of what we know about the Kassites comes from tablets found in Nippur. A new capital west of Baghdad, Dur Kurigalzu, competing with Babylon, was founded and named after Kurigalzu I (c. 1400-c. 1375).

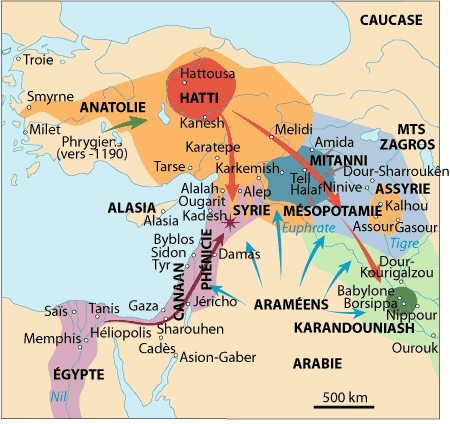

The Kassites rapidly adopted the Babylonian language, customs, and traditions. They introduced the use of small stone steles known as kudurrus, a tradition maintained by later dynasties until the 7th century BC. Surprisingly no inscription or document in the Kassite language has been preserved. Kassite kings established trade and diplomacy with Assyria, Egypt, Elam, and the Hittites, and the Kassite royal house intermarried with their royal families. There were foreign merchants in Babylon and other cities, and Babylonian merchants were active from Egypt (a major source of Nubian gold) to Assyria and Anatolia. But the catastrophic collapse at the end of the bronze age was starting to dramatically unfold with many of the cities of the Levant experiencing destruction. During the reign of Kashtiliash IV (1232-1225), Babylonia waged war on two fronts at the same time, against Elam and Assyria, ending in the invasion and destruction of Babylon by Tukulti-Ninurta of Assyria (Chronicle of Tukulti-Ninurta I) perhaps around 1225 BC. The situation had improved by the time of King Melišipak, but during his reign Emar in Syria (Mitanni, an ally of Egypt) was sacked in 1187 BC and and the Hittite capital of Hattusa was burnt to the ground sometime around 1180 BC.

Between 1206 and 1150 BCE, the cultural collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria, and the New Kingdom of Egypt in Syria and Canaan interrupted trade routes and severely reduced literacy. From Greece to Egypt, the social and political system of the Bronze Age collapsed. Amid war and chaos, the great palaces of the ancient Greek kings and the strong fortress of Troy were destroyed. Hittite rule in Asia Minor was ended forever, and the Hittites disappeared from history. The cities of Cyprus and Syria (Mitanni) were destroyed. A mysterious group, the Sea Peoples were a confederacy of seafaring raiders of the second millennium BC who sailed around the eastern Mediterranean, causing political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egyptian territory. Egypt fought against them for its very existence. The battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC was the first contact of Egypt with the Sea Peoples. Subsequently Ramesses III, the second king of the Egyptian 20th Dynasty, who reigned for most of the first half of the 12th century BC, was forced to deal with a later wave of invasions of the Sea Peoples, and by the way won. Ramses tells us that, having brought the imprisoned Sea Peoples to Egypt, he “settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Some scholars suggest it is likely that these “strongholds” were fortified towns in southern Canaan, which would eventually become the five cities (the Pentapolis) of the Philistines.

These were not typical invasions but rather a mass migration from places unknown. The invaders, that is, the replacement cultures, apparently made no attempt to retain the cities’ wealth but instead built new settlements of a materially simpler cultural and less complex economic level on top of the ruins, particularly in Canaan. The fact that several civilizations around 1175 BCE collapsed has led suggestion that the Sea Peoples may have been involved in the end of the Hittite, Mycenaean and Mitanni kingdoms.

Many, but not all, of the Canaanite cities were destroyed, international trade collapsed, and the Egyptians withdrew. At the end of this period a new landscape emerges: the northern Canaanite cities still existed, more or less intact, and became the Phoenicians; the highlands behind the coastal plains, previously largely uninhabited, were rapidly filling with villages, largely Canaanite in their basic culture but without the Bronze Age city-state structure; and along the southern coastal plain there are clear signs that a non-Canaanite people had taken over the former Canaanite cities while adopting almost all aspects of Canaanite culture, the Philistines and the Jewish states of Judah and Israel. The Arameans never had a unified nation; they were divided into small independent kingdoms across parts of the Near East, particularly in what is now modern Syria. By contrast, the Aramaic language came to be the lingua franca of the entire Fertile Crescent, by Late Antiquity developing into the literary languages such as Syriac and Mandaic (see my post on the Syriac Church). Arameans are mostly defined by their use of the West Semitic Old Aramaic language (1100 BC–AD 200), first written using the Phoenician alphabet, over time modified to a specifically Aramaic alphabet. The 2nd and 3rd centuries were the golden age of Palmyra, home to the Arameans, when it flourished through its extensive trading and favored status under the Romans.

A really nice article on the Kassites can be found on the Encyclopaedia Iranica: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kassites