The process of creating useful and visually pleasing petroglyphs is one of the more difficult art forms, related more to creating a stone statue than painting. Unlike cave paintings that are added to the rock, petroglyphs involve removing material, in particular the desert varnish or patina that covers rocks in the desert. Today this would be difficult and take time, even with our modern steel tools, back then they only had stone tools making the process long and laborious. To cut a hard stone you would need a harder stone, preferably with some kind of point to focus the energy. Aside from the technical difficulties, there is the matter of artistic depiction of various animals, experiences and ideas. To communicate even relatively simple things, given the relatively crude stone canvas, the essence of the item being depicted must be communicated unambiguously, to translate to even strangers speaking a different language. While this discussion is directed primarily at Little Petroglyph Canyon, the principles are applicable to most petroglyphs.

Geology of Little Petroglyph Canyon

A general geological description of the Coso Mountains would be basaltic flows with overlying rhyolite domes and flows. Conchoidal fracture describes the way that brittle materials break or fracture when they do not follow any natural planes of separation. As you can see, rhyolite breaks into concave fragments and has a fine grain, perfect for making arrowheads or projectile points.

Schist is a foliated metamorphic rock made up of plate-shaped mineral grains that are large enough to see with an unaided eye. It usually forms on a continental side of a convergent plate boundary where sedimentary rocks, such as shales and mudstones, have been subjected to compressive forces, heat, and chemical activity. This metamorphic environment is intense enough to convert the clay minerals of the sedimentary rocks into platy metamorphic minerals such as muscovite, biotite, and chlorite. To become schist, a shale must be metamorphosed in steps through slate and then through phyllite. If the schist is metamorphosed further, it might become a granular rock known as gneiss. The Coso Volcanic Field is a geologically active area with a variety of rock types. I have included this short introduction to rhyolite (fine grained) and schist (large grained plates) to emphasize the natural cracks you might encounter in the rocks.

Desert Varnish or Patina

Desert varnish or rock varnish is an orange-yellow to black coating found on exposed rock surfaces in arid environments. Desert varnish forms only on physically stable rock surfaces that are no longer subject to frequent precipitation, fracturing or wind abrasion. The varnish is primarily composed of particles of clay along with iron, barium and manganese oxides. Originally scientists thought that the varnish was made from substances drawn out of the rocks it coats. Microscopic and microchemical observations, however, show that a major part of varnish is clay, which could only arrive by wind. Clay, then, acts as a substrate to catch additional substances that chemically react together when the rock reaches high temperatures in the desert sun. Wetting by dew is also important in the process. Shiny, dense and black varnishes form on basalt, fine quartzites (like rhyolite) and metamorphosed shales (like schist) due to these rocks’ relatively high resistance to weathering. Desert Varnish is generally no thicker than 200 micrometers and the thickness is not indicative of age. Stratifications within the varnish can reveal the general age of the desert varnish assembly by correlations with known wet and dry periods in history. Some authors also believe the desert varnish is associated with bacteria. Using the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, scientists were recently able to map the different compounds in rock varnish, finding that the high concentration of manganese in continuous layers must be related to ongoing biological processes as opposed to a long-term chemical reactions on the rock surface due to sun exposure. Genomic sequencing of the stain material also revealed an abundance of Chroococcidiopsis bacteria, which produce extra manganese to protect against harsh solar radiation, effectively creating a natural sunscreen for themselves. That extra metal is left behind when the cells die and then oxidized to form the dark, smooth surface.

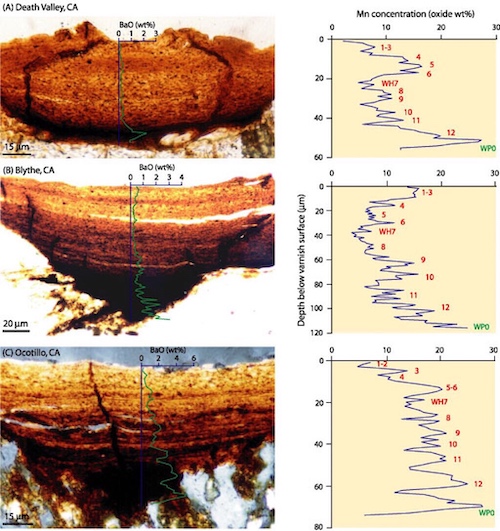

Optical (left) and chemical (right) microstratigraphies in rock varnish from three localities along a north-south traverse in the drylands of western USA. Note that Manganese (Mn) and Barium (Ba) contents in the Holocene (11,700 years to present) portion of each varnish microstratigraphy are much lower than that in the terminal Pleistocene/Ice Age (2,588,000 to 11,700 years before present) portion of the microstratigraphy. Also note that the average Holocene Mn and Ba contents in the varnishes exhibit a general trend along the traverse, from the lowest in Death Valley to the highest in Ocotillo, which appears to reflect the present-day effective moisture gradient in southern California. WH1-WH12 and WP0 in the right panel identify Mn-rich peaks on each probe line profile that correspond to the Holocene (11,700 years to present) and terminal Pleistocene/Ice Age (2,588,000 to 11,700 years before present) dark layers seen in the optical microstratigraphies. WH = Wet event in Holocene, WP = Wet event in Pleistocene. This shows that the striations in desert varnish may act much like tree rings, indicating wet and dry periods in history. In fact the tree ring data can be correlated with desert varnish measurements to identify wet and dry periods in the history of the desert.

Old Petroglyphs

So we know desert varnish is deposited on certain kinds of rocks to give them a dark brown color and that this process occurs over thousands of years. Seen above are two petroglyphs which have re-acquired desert varnish inside the petroglyph and can only be seen by differences in reflected light. Certainly, these petroglyphs are old but it is impossible to estimate the actual age based solely on the re-acquired desert varnish. The process of making a petroglyph involves the pecking away of of desert varnish, revealing the lighter colored rock below. Unfortunately the uneven surface of a petroglyph is perfect for rapidly re-acquiring desert varnish and the rate of this process is so dependent on location and orientation that is is difficult if not impossible to date. We are certainly allowed to guess the age based on known rates of accumulation based on data from Liu and Broecker. In their study, rates of accumulation of desert varnish vary from 40 micrometers/thousand years to around 5–15 micrometers/thousand years in areas around the Coso range. My personal guess is that these petroglyphs are at least several thousand years old.

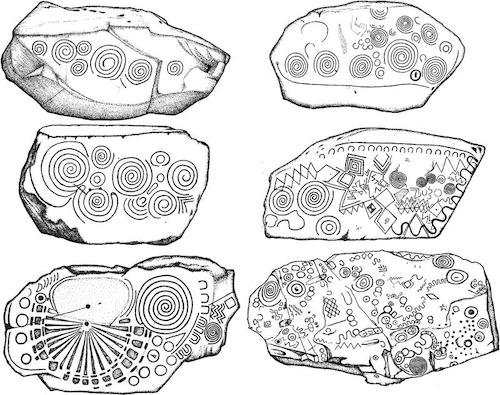

Spiral Petroglyphs

One of the most common geometric motifs is the spiral, painted and carved throughout the ancient world. And yet the symbolic meaning of the spiral in prehistoric art is speculative. Some argue it may have represented the sun, or the portal to a spirit world. Perhaps it represented life itself, or life beyond life perhaps eternity. Or possibly it may have had a more prosaic, functional purpose, that of a calendar device, employed to deconstruct time into chapters, seasons and solstices. Two spirals together often represented the eternal bond between a man and his wife although no one can say what this particular petroglyph means.

The dual centered spiral was often thought to represent the balance of nature, much like the Yin Yang is the balance of masculine and feminine. This is a sacred symbol of the Celtic goddess Epona. She is a horse goddess of Earth. Epona was invoked during the equinoxes (Autumn and Vernal) to bring about smooth passage of the seasons. Each end of the spiral can express a polarity. For example: Left vs Right, Night vs Day, Death vs Life, Moon vs Sun, Good vs Evil, etc. In fact,the entire universe can be viewed as elegantly perched on polar or opposite energies. There cannot be a push without a pull or a nighttime without daytime. Therefore, this double spiral is perfect symbol that portrays the balance between opposite influences. In New Zealand the Moana ideology of Ta-Vā, ( Theory of Reality) and the supporting ideal of teu la vā (sacred connections), relationships between nature, things and people are considered interconnected and symbiotic. Importantly, they are viewed as eternal; in either circular or spiral configurations.

Triple Spirals and Trinity Symbols

As long as we are discussing spirals, I thought I would include the subject of triple spirals. Newgrange is a prehistoric funeral monument in County Meath, Ireland. It is an exceptionally grand passage tomb built during the Neolithic period, around 3200 BC, making it older than Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. The kerbstones, large blocks of decorated stone, are adorned with geometric patterns, including spirals. The patterns on several stones have been interpreted as calendar devices that enable the calculation of the months and the exact length of the year. They suggest an awareness of a 19-year lunar cycle.

The Celtic triple spiral or triskele is sometimes called the spiral of life. Discovered in the Newgrange site the spiral (or “tri-spiral”) design is engraved on the stone in front of the entrance and represents one of the most famous Irish Megalithic scribings. The triskelion is an ancient magical symbol for many cultures. Most consider the symbol as a Celtic design, it actually appeared in Ireland over 2,500 years prior to the arrival of the Celts. The triskelion symbol appears in many early cultures, the first in Malta (4400–3600 BCE) and in the astronomical calendar at the famous megalithic tomb of Newgrange in Ireland built around 3200 BCE, Mycenaean vessels, on coinage in Lycia, and on staters of Pamphylia (at Aspendos, 370–333 BCE) and Pisidia. Celtic interpretations include the matriarchal maiden/mother/crone, future/past/present, sun/moon/earth and for later Christians father/son/holy ghost among many other interpretations. The differences lay in the intent of the symbol, and the tribe that was using it at the time in Celtic history. The negative space in the center of this symbol symbolizes the center of all influences. In personal ritual, it could represent the self at the center of trinity influences. In a tribe, the center is the heart of the people with the three elements creating an unbreakable union.

Water Petroglyphs

Cup and ring marks or cup marks are a form of prehistoric art commonly found in the Atlantic seaboard of Europe, a few examples in Mesoamerica and in Brasil at Pedra Preta. In most of the Mesoamerican sites with cup-and-ring marks, the designs occur in areas of privileged access or sacred areas. For instance, both of the carved boulders from Totomixtlahuaca and Ayotoxtla in Guerrero were situated within a few hundred meters of sacred caves that continued to be used during seasonal rituals. At Chalcatzingo, MCR–17 was found near the central plaza but next to Terrace 2, the location of an elite residence. Smith and Walker have suggested that cup-and-ring marks might be symbolically linked to water, having sacred associations in late prehistoric society. As evidence, they noted that a number of the larger cups, which they refer to as basins, would have collected rain water. They believed that cup-and-ring markings looked like the ripples produced when raindrops hit water. The petroglyph from Little Petroglyph Canyon shows a natural depression in the rock and water stains suggesting that water settled there after a rain. This may be a modified cup and rings or possibly a human hand catching the rain. In either case I think it is reasonable to associate this petroglyph with water in a symbolic/sacred context.

I recognize the rock art examples from Europe are not petroglyphs but the symbols they convey are relevant and the older petroglyphs are often carved deeply into the stone. I hope you enjoyed this post, there are more petroglyphs to come, please leave a comment.

References:

Microprobe Elemental Mapping of Varnish Chemistry

How Fast Does Rock Varnish Grow? Liu and Broecker

Rock Varnish: Recorder of Desert Wetness

Quantum Stones on the Meaning of Spirals

Walking backwards into the future: Indigenous wisdom within design education

Cup-and-Ring Marked Stones in Ancient Mesoamerica

The main pre-colonial archaeological sites in Brazil. Teaching History

Smith, Brian A.; Walker, Alan A. (2008). Rock Art and Ritual: Interpreting the Prehistoric Landscapes of the North York Moors. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978–0752446349.

Rock varnish, the thin, dark coating on rocks’ surfaces, is an indicator of life

An ecophysiological explanation for manganese enrichment in rock varnish