One of the reasons I went to Turkey this summer was to visit some of the famous archeology museums and sites open to the public. Because of the ancient heritage of modern day Turkey, involving many of the great and small empires of history, and the lasting imprint they left on the country, ruins, treasures, customs, and of course food, Turkey is a microcosm of the history of the Middle East. The mosaic fragment seen above, named by the press “Gypsy Girl” when it was rediscovered in excavations during the winter of 1998-1999 in the Turkish city Zeugma is a perfect example. A special mosaic technique was used to make the eyes more realistic. The haunting look reminds us of the best of women's portraits including the Mona Lisa, Girl with a Pearl Earring, Bathsheba, and of course the famous Afghan Girl by Steve McCurry from 1983. She was discovered in 1998-1999 in the House of Menad in Zeugma and dates from the 2nd-3rd century CE. Almost all the other mosaics in the house had been looted. She currently resides at the relatively new Zeugma Mosaic Museum (2011) in Gaziantep, Turkey.

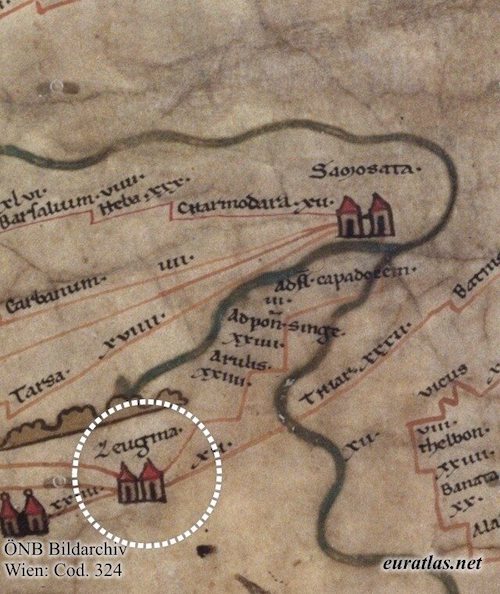

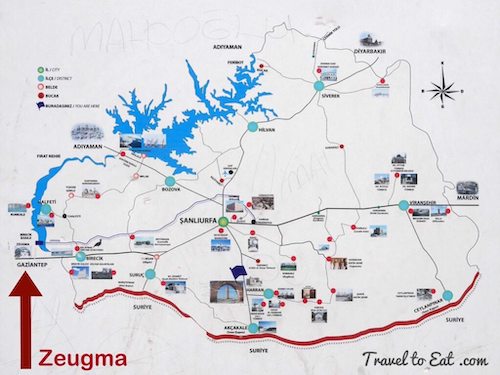

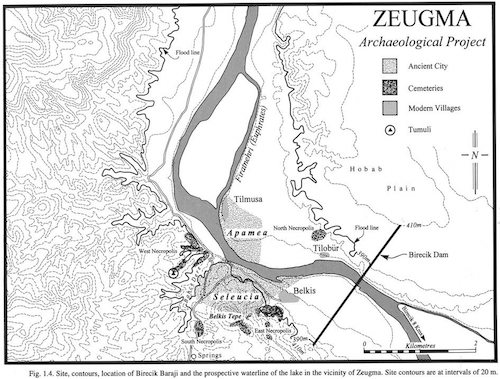

Zeugma, which was founded in the 3rd-4th century B.C. by Seleucus Nicator I, one of Alexander the Great’s commanding generals, is situated at one of the easiest fording places on the Euphrates. Maybe therefore its name, ‘Zeugma’, means ‘bridgehead’ or ‘crossing place’. But Zeugma's story begins millennia before the dam was constructed. In the third century B.C., Seleucus I Nicator (“the Victor”) established a settlement he called Seleucia, probably a katoikia, or military colony, on the western side of the river. On its eastern bank, he founded another town he called Apamea after his Persian-born wife. The two cities were physically connected by a pontoon bridge, but it is not known whether they were administered by separate municipal governments, and nothing of ancient Apamea, nor the bridge, survives. The breakup of Alexander the Great's vast empire was not pretty. Ptolomy grabbed Egypt and Seleucus Nicator I used every opportunity to enlarge his territory:

“Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.”

— Appian, The Syrian Wars

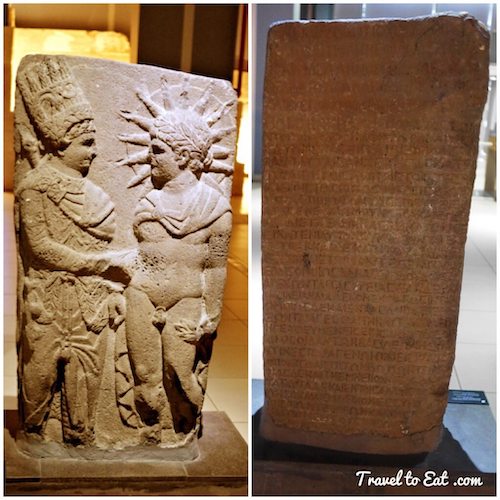

His successors were unfortunately not as successful in maintaining the empire. Over a period of about 300 years, the Selucids served as a buffer state between the encroaching Romans in the west and the Parthian Persians in the east. The Selucids existed solely because no other nation wished to absorb them, as they constituted a useful buffer between their other neighbors. The Selucids actually made steles in temples to show that the Greek and Persian gods approved of their buffer state. As seen above, King Antiochus I (son of Seleucus Nicator) is shown shaking the hand of Apollo-Mithras-Helios while a second stele shows King Antiochus shaking the hand of Heracles-Hercules. The nomos (law) inscriptions on the reverse of both steles are inscribed with the policies of combining Greek and Persian deities over the lands ruled by Antiochus.

In 64 B.C., the Romans, specifically Pompey, conquered Seleucia, renaming the town Zeugma, which means “bridge” or “crossing” in ancient Greek. After the collapse of the Selucid Empire, the Romans added Zeugma to the lands of Antiochus I Theos of Commagene as a reward for his support of General Pompey during the conquest. Thanks to its strategic situation on an east-west axis, the city quickly grew and developed, becoming one of the four major cities of the Commagene Kingdom founded in the 1st century B.C. in the post-Hellenistic period. The eastern borders of the Roman Empire changed many times, of which the longest lasting was the Euphrates river, eventually to be left behind as the Romans defeated their rivals, the Parthians, with the march on their capital, Susa in 115. The Parthians were a group of Iranian peoples that ruled most of greater Iran that is in modern day Iran, western Iraq, Armenia and the Caucasus. In 118 Hadrian decided that it was in Rome's interest to re-establish the Euphrates as the limit of its direct control. Hadrian returned to the status quo, and surrendered the territories of Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Adiabene to their previous rulers and client-kings and didn't attempt to romanize the Parthian Empire.

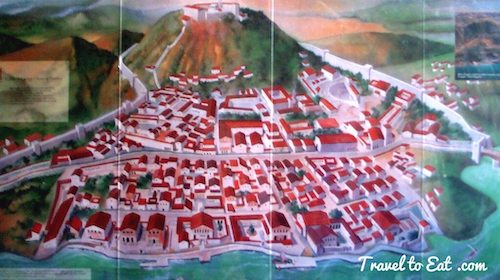

The city’s location was considered so important by the Romans that Zeugma became a vital military center where tolls were collected on commerce and travelers. During the Roman Era, the Legio IV Scythica was camped in Zeugma starting in 18 CE. There were only eight legions in all of Rome's Asian provinces between the Black Sea and the Red and two of them were located at Samosata and Zeugma within 70 km of one another, an indicator of the military significance of these places. For about two centuries the city was home to high-ranking officials and officers of the Roman Empire, who transferred their cultural understanding and sophisticated lifestyle into the region. At one point the city was home to more than 70,000 people. In the process, wealthy residents, businessmen, military officers, governors and other notables built impressive homes and villas distinguished by magnificent mosaics — on floors, in pools, courtyards, kitchens and elsewhere. Because of Zeugma’s position at the center of international trade and commerce, these mosaics represent a treasure trove of information about the interaction and assimilations of ancient cultures over the centuries. However, the good times in Zeugma declined along with the fortunes of the Roman Empire. After the Sassanids from Persia attacked the city in 253 CE, its luxurious villas were reduced to ruins and used as shelters for animals. The city’s new inhabitants were mainly rural people who employed only simple building materials that did not survive. Zeugma’s grandeur and importance would remain forgotten for more than 1,700 years.

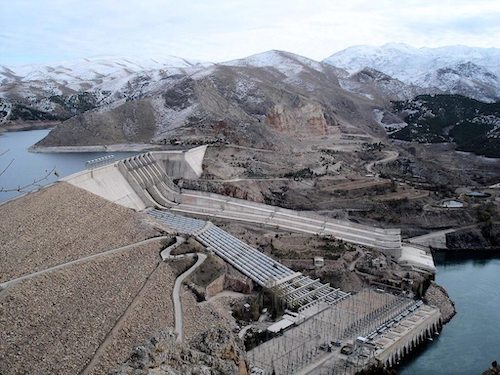

The first scientific study which proved that Zeugma is in the same place as modern Belkıs, was published in 1917. The excavation studies in the Ancient City were started in 1992 under the management of the Gaziantep Museum Directorate of the Ministry of Culture, the General Directorate of Monuments and Museums. French archaeology teams joined the studies from 1996. When mosaic fragments were discovered during construction of the Birecik Dam wall which commenced in 1996, Gaziantep Museum had the work halted while excavations were carried out that revealed a Roman bath and gymnasium, and 36 mosaic panels which were added to the museum collection. In 1997, on the clay quarry area in front of the dam wall a large Bronze Age cemetery was discovered and excavated. Nearly 8,000 pottery vessels were found in 320 graves going back to the early Bronze Age.

In 2000, the construction of the massive Birecik Dam on the Euphrates River, less than a mile from the site, began to flood the entire area in southern Turkey. Immediately, a ticking time-bomb narrative of the waters, which were rising an average of four inches per day for six months, brought Zeugma and its plight global fame. The water, which soon would engulf the archaeological remains, also brought increasing urgency to salvage efforts and emergency excavations that had already been taking place at the site, located about 500 miles from Istanbul, for almost a year. The media attention Zeugma received attracted generous aid from both private and government sources. The results can be seen at the Zeugma Mosaic Museum in Gaziantep. This may sound difficult to believe, considering that at least 25 percent of the western bank of the ancient town now sits below almost 200 feet of water and the city’s eastern bank is completely submerged, but there is still much left to see, and to excavate, in Zeugma. With the imminent threat of the rising water having abated, archaeologists including Kutalmis Gorkay of Ankara University, who has directed work at Zeugma since 2005, have focused their attention on new projects as well as on conservation and preservation of what remains above the water.

The outcome of the controversy concerning the dam and the flooding of Zeugma has been both good and bad. Emergency efforts saved many mosaics and seals which are on display in a new $30 million museum in Gaziantep. In 2005, the direction of the Zeugma excavations and the coordination of all scientific works on the site were placed by Turkey’s Board of Ministers under the direction of Ankara University, allowing comprehensive and long-term plans for the excavations to be developed. At the same time, the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism allocated funds for the expropriation of land, security against looting, restoration, conservation and archaeological excavations. Construction of a $1.5 million shelter structure for the conservation of two Roman houses and their mosaics was launched in 2006 and completed in 2010, enabling the display of mosaics and frescoes in situ. Archeology work continues there. The TAY (Archaeological Settlements of Turkey) Project was set up to build a chronological inventory of findings for the cultural heritage of Turkey – an important component of World Heritage sites – and to share this information with the international community. This post is the first in a series that will examine the museum, the actual site, and the impact of the Birecik Dam.

[mappress mapid=”28″]

References:

TAY: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/02/0202_turkeyweb.html

TAY: http://tayproject.org/enghome.html

Zeugma Blog: http://zeugmamosaicmuseum.blogspot.com/

Zeugma Mosaics: http://comenius-legends.blogspot.com/2010/07/zeugma-mosaics-gazianteps-crowning.html

Zeugma Tragedy: http://www.humanities.uwa.edu.au/research/cah/zeguma/1990

Unesco: http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5726/