Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was born in the Franconian city of Nuremberg, one of the strongest artistic and commercial centers in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. He was a brilliant painter, draftsman, and writer, though his first and probably greatest artistic impact was in the medium of printmaking. More than any other Northern European artist, Dürer was engaged by the artistic practices and theoretical interests of Italy. He visited the country twice, from 1494 to 1495 and again from 1505 to 1507, absorbing firsthand some of the great works of the Italian Renaissance, as well as the classical heritage and theoretical writings of the region. While in Nuremberg in 1512, the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian I enlisted Dürer into his service, and Dürer continued to work mainly for the emperor until 1519. The emperor is depicted here as an elegant private gentleman. The desired effect of dignity and power is achieved by the manner in which the emperor fills the frame and the brilliant execution of the fur collar. Several different interpretations have been suggested for the pomegranate in the emperor’s hand: as a private proxy for the imperial orb, as a reference to the myth of Persephone and thus a reference to death, and as an allusion to the conquest of Granada by the Christian armies in 1492.

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman is a small bust length oil on elm panel painting by the Dürer from 1505. It was executed, along with a number of other high society portraits, during his second visit to Italy. The woman wears a patterned gown with tied-on sleeves that show the chemise beneath. Her hair frames her face in soft waves, and back hair is confined in a small draped cap. The work’s harmony and grace is achieved through its mixtures of tones, from her pale, elegant skin and reddish blond hair and to her black-and pearl necklace and highly-fashionable patterned dress, all of which are highlighted against a flat black background. The work was not identified as a Dürer original until it was found in a private Lithuanian collection in 1923.

In the autumn of 1505, Dürer made a second journey to Italy, where he remained until the winter of 1507. Once again he spent most of his time in Venice. Of the Venetian artists, Dürer now most admired Giovanni Bellini, the leading master of Venetian early Renaissance painting, who, in his later works, completed the transition to the High Renaissance. Dürer’s pictures of men and women from this Venetian period reflect the sweet, soft portrait types especially favoured by Bellini. The half-length portraits of young men and women painted between 1505 and 1507, including the one seen above, seem to be entirely in the style of Bellini. In these paintings there is a flexibility of the subject, combined with a warmth and liveliness of expression and a genuinely artistic technique, that Dürer otherwise rarely attained. I must say, I love these two portraits. They combine the angular German character with the elegant, warm tones of the Renaissance.

The altarpiece depicts the legend of the ten thousand Christians who were martyred on Mount Ararat, in a massacre perpetrated by the Persian King Saporat on the command of the Roman Emperors Hadrian and Antonius. Dürer had depicted this massacre a decade earlier in a woodcut. The painting was commissioned by Frederick the Wise, who owned relics from the massacre, and it was placed in the relic chamber of his palace church in Wittenberg. Although Dürer had never before tackled a painting with so many figures, he succeeded in integrating them into a flowing composition using vibrant color. Frederick III of Saxony, also known as Frederick the Wise, was Elector of Saxony (from the House of Wettin) from 1486 to his death.

The Nuremberg merchant Matthäus Landauer founded the “Twelve Brothers’ House” as a home for aged and destitute craftsmen. He commissioned Dürer to do the altar-piece for the associated chapel. The All Saints’ Picture depicts the adoration of the Holy Trinity by the heavenly angels and saints united in the community of “God’s state” as well as by earthly believers of all times. On the left hand side of the picture, the founder Matthäus Landauer is kneeling surrounded by the righteous. Set apart from the heavenly vision on earth, Dürer has painted himself in festive garments with an inscription board bearing his signature. I spent so much time admiring this painting that my own pictures did not turn out, so I used the picture from Wikipedia. This painting is indeed a masterpiece and you have to see it for yourself.

To me, it is a bit reminiscent of Raphael’s Transfiguration at the Vatican Museum, although Raphael has picked a more joyful and less busy subject. Despite the regard in which he was held by the Venetians, Dürer returned to Nuremberg from his second trip to Venice by mid-1507, remaining in Germany until 1520. His reputation had spread throughout Europe and he was on friendly terms and in communication with most of the major artists including Raphael, Giovanni Bellini, and mainly through Lorenzo di Credi, Leonardo da Vinci. Dürer had achieved an international reputation as an artist by 1515, mostly due to his engravings, when he exchanged works with Raphael. His success in spreading his reputation across Europe through prints was undoubtedly an inspiration for major artists such as Raphael, Titian, and Parmigianino, all of whom collaborated with printmakers in order to promote and distribute their work.

This depiction of the Madonna differs from others in the long series painted by Dürer in the marked difference between Mary’s head and the infant Jesus, both in terms of composition and artistic execution. The Madonna’s gently smiling countenance derives from Dutch tradition. In contrast, the child’s posture twisted in the body’s axis can be traced back to the Italian Early Renaissance. The child’s powerful physicality, achieved by Dürer by means of soft, finely spread shadows, is Italian in origin. To be honest, I love the portrait of the Madonna while the child has a big head and an unpleasant, cramped expression of the lips.

Among the three portraits Dürer painted in 1526 – Hieronymus Holzschuher, Jakob Muffel, and Johannes Kleberger (1486-1546) – the last was distinct for the format of the frame and for the depiction: the man, in fact, is sketched in a bas relief, in a half-bust, and inserted, classically, in a clypeus. It is an unusual depiction among Dürer’s works, which has largely puzzled art historians. But since portraits in bas-relief on medallions were often found on the facades of Renaissance buildings in France, where Kleberger lived for a long time, it is quite likely that the patron himself had requested the artist to portray him in this way. Dürer’s innovation was that of vivifying the portrait in bas relief on a medallion of fake stone, giving him the colors of a live, if pale, complexion. Dürer takes up again the age-old theme of the comparison of the figurative arts, or more specifically, the discussion of the predominance of one on the other. He interprets this discussion by presenting an image in sculpture, with its light and shadow, giving at the same time the signs of a painted portrait. Thus, even while maintaining in the steadiness of the gaze, the immobile plasticity of a sculpted image characteristic of the portraits of emperors during classical times, the result is a particularly vivid portrait, since it expresses the power of the subject and his extremely ambitious character.

No post on Dürer would be complete without at least a few engravings. The third and most famous woodcut from Dürer’s series of illustrations for The Apocalypse, the Four Horsemen presents a dramatically distilled version of the passage from the Book of Revelation (6:1–8). Transforming what was a relatively staid and unthreatening image in earlier illustrated Bibles, Dürer injects motion and danger into this climactic moment through his subtle manipulation of the woodcut. The parallel lines across the image establish a basic middle tone against which the artist silhouettes and overlaps the powerful forms of the four horses and riders—from left to right, Death, Famine, War, and Plague (or Pestilence). Their volume and strong diagonal motion enhance the impact of the image, offering an eloquent demonstration of the masterful visual effects Dürer was able to create in this medium.

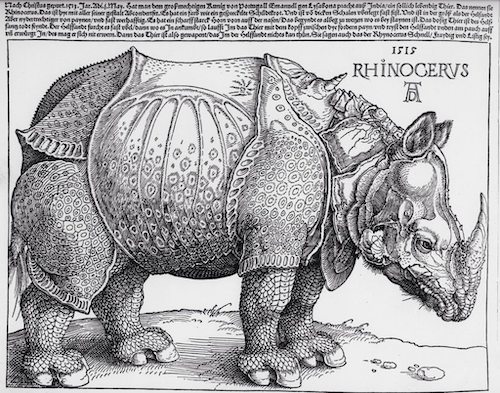

In 1515, he created his woodcut of a Rhinoceros which had arrived in Lisbon from a written description and sketch by another artist, without ever seeing the animal himself. An image of the Indian rhinoceros, the image has such force that it remains one of his best-known and was still used in some German school science text-books as late as last century. In fact I found the image on the website of the Rhinoceros Resource Center. In the years leading to 1520 he produced a wide range of works, including the woodblocks for the first western printed star charts in 1515 and portraits in tempera on linen in 1516.

Under the influence of Italian theory, Dürer became increasingly drawn to the idea that the perfect human form corresponded to a system of proportion and measurements. Near the end of his life, he wrote several books codifying his theories: the Underweysung der Messung (Manual of measurement), published in 1525, and Vier Bücher von menschlichen Proportion (Four books of human proportion), published in 1528, just after his death. Dürer’s fascination with ideal form is manifest in Adam and Eve. The first man and woman are shown in nearly symmetrical idealized poses: each with the weight on one leg, the other leg bent, and each with one arm angled slightly upward from the elbow and somewhat away from the body. The figure of Adam is reminiscent of the Hellenistic Apollo Belvedere, excavated in Italy late in the fifteenth century. The first engravings of the sculpture were not made until well after 1504, but Dürer must have seen a drawing of it. Dürer was a complete master of engraving by 1504: human and snake skin, animal fur, and tree bark and leaves are rendered distinctively. The branch Adam holds is of the mountain ash, the Tree of Life, while the fig, of which Eve has broken off a branch, is the forbidden Tree of Knowledge. Four of the animals represent the medieval idea of the four temperaments: the cat is choleric, the rabbit sanguine, the ox phlegmatic, and the elk melancholic. Before the Fall, these humors were held in check, controlled by the innocence of man; once Adam and Eve ate from the apple of knowledge, all four were activated, all innocence lost.

I hope you have enjoyed this foray into the world of Albrecht Dürer and if you have an opportunity, try to see his work in person. He is one of the great figures of the Renaissance, not too different from Leonardo da Vinci in terms of the breadth of his accomplishments, a naturally born genius in the arts and letters.

References:

Kunsthistorisches Museum: http://bilddatenbank.khm.at/KHMSearch/viewPerson?id=68

Dürer Biography: http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/bio/d/durer/biograph.html

Met Museum: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/durr/hd_durr.htm

Kleberger: http://www.wga.hu/html_m/d/durer/1/10/4kleberg.html

Rhino Resource Center: http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/images/Durers-rhino-1515_i1218990307.php?type=all_images&sort_order=desc&sort_key=added

Printmaking: http://www.robinurton.com/history/printmaking.htm